Ellen Willis

Appearance

Ellen Willis (December 14 1941 – November 9 2006) was an American essayist and critic. She was director of the cultural journalism program at New York University and co-founder of the feminist group Redstockings. She played an important role in the development of sex-positive feminism.

Quotes

[edit]

- Under present conditions, people are preoccupied with consumer goods not because they are brainwashed but because buying is the one pleasurable activity not only permitted but actively encouraged by our rulers. The pleasure of eating an ice cream cone may be minor compared to the pleasure of meaningful, autonomous work, but the former is easily available and the latter is not. A poor family would undoubtedly rather have a decent apartment than a new TV, but since they are unlikely to get the apartment, what is to be gained by not getting the TV?

- There is a persistent myth that a wife has control over her husband’s money because she gets to spend it. Actually, she does not have much more financial authority than the employee of a corporation who is delegated to buy office furniture or supplies. The husband, especially if he is rich, may allow his wife wide latitude in spending — he may reason that since she has to work in the home she is entitled to furnish it to her taste, or he may simply not want to bother with domestic details — but he retains the ultimate veto power. If he doesn’t like the way his wife handles his money, she will hear about it.

- "Women and the Myth of Consumerism," Ramparts (1969)

- Dylan is free now to work on his own terms. It would be foolish to predict what he will do next. But hopefully he will remain a mediator, using the language of pop to transcend it. If the gap between past and present continues to widen, such mediation may be crucial. In a communications crisis, the true prophets are the translators.

- "Dylan" in Representative Men : Cult Heroes of Our Time (1970) edited by Theodore L. Gross

- While liberals appeared to be safely in power, feminists could perhaps afford the luxury of defining Larry Flynt or Roman Polanski as Enemy Number One. Now that we have to cope with Jerry Falwell and Jesse Helms, a rethinking of priorities seems in order.

- "Lust Horizons: Is the Woman's Movement Pro-Sex?" (1981), No More Nice Girls: Countercultural Essays (1992)

- These apparently opposed perspectives meet on the common ground of sexual conservatism. The monogamists uphold the traditional wife's "official" values: emotional commitment is inseparable from a legal/moral obligation to permanence and fidelity; men are always trying to escape these duties; it's in our interest to make them shape up. The separatists tap into the underside of traditional femininity — the bitter, self-righteous fury that propels the indictment of men as lustful beasts ravaging their chaste victims. These are the two faces of feminine ideology in a patriarchal culture: they induce women to accept a spurious moral superiority as a substitute for sexual pleasure, and curbs on men's sexual freedom as a substitute for real power.

- "Lust Horizons: Is the Woman's Movement Pro-Sex?" (1981), No More Nice Girls: Countercultural Essays (1992)

- The drug war has nothing to do with making communities livable or creating a decent future for black kids. On the contrary, prohibition is directly responsible for the power of crack dealers to terrorize whole neighborhoods. And every cent spent on the cops, investigators, bureaucrats, courts, jails, weapons, and tests required to feed the drug-war machine is a cent not spent on reversing the social policies that have destroyed the cities, nourished racism, and laid the groundwork for crack culture.

- The centerpiece of the cultural counterrevolution is the snowballing campaign for a "drug-free workplace" — a euphemism for "drug-free workforce," since urine testing also picks up for off-duty indulgence. The purpose of this '80s version of the loyalty oath is less to deter drug use than to make people undergo a humiliating ritual of subordination: "When I say pee, you pee." The idea is to reinforce the principle that one must forfeit one's dignity and privacy to earn a living, and bring back the good old days when employers had the unquestioned right to demand that their workers' appearance and behavior, on or off the job, meet management's standards.

- "Hell No, I Won't Go: End the War on Drugs," The Village Voice (19 September 1989)

- Whatever their limitations, Freud and Marx developed complex and subtle theories of human nature grounded in their observation of individual and social behavior. The crackpot rationalism of free-market economics merely relies on an abstract model of how people "must" behave.

- Letter to The New York Times (27 February 1997)

- The project of organizing a democratic political movement entails the hope that one's ideas and beliefs are not merely idiosyncratic but speak to vital human needs, interests and desires, and therefore will be persuasive to many and ultimately most people. But this is a very different matter from deciding to put forward only those ideas presumed (accurately or not) to be compatible with what most people already believe.

- By definition, the conventional wisdom of the day is widely accepted, continually reiterated and regarded not as ideology but as reality itself. Rebelling against "reality," even when its limitations are clearly perceived, is always difficult. It means deciding things can be different and ought to be different; that your own perceptions are right and the experts and authorities wrong; that your discontent is legitimate and not merely evidence of selfishness, failure or refusal to grow up. Recognizing that "reality" is not inevitable makes it more painful; subversive thoughts provoke the urge to subversive action. But such action has consequences — rebels risk losing their jobs, failing in school, incurring the wrath of parents and spouses, suffering social ostracism. Often vociferous conservatism is sheer defensiveness: People are afraid to be suckers, to get their hopes up, to rethink their hard-won adjustments, to be branded bad or crazy.

- "We Need a Radical Left," The Nation (29 June 1998)

- The idea that lack of paternal guidance can explain today's masculinity crisis doesn't make sense. I suspect rather that underneath the sons' charge that their fathers did not teach them how to be men lies another, unadmitted complaint — that their fathers taught them only too well how to be men, and they are choking on the lesson. These men, as boys, faced the age-old tradeoff: If you undergo the painful process of renouncing the "feminine" aspects of your humanity and follow your father into manhood (and what choice do you have, really?) you will share in the spoils of the superior half of the race. Now, as men, they find that the spoils are far more meager than expected. No wonder they feel betrayed.

- Surely we have had enough of confusing maleness with "usefulness" and other human virtues. If men had a more modest view of what their masculinity ought to entail, perhaps they could move on from debilitating feelings of loss to tackling their real economic and political problems.

- "How Now, Iron Johns?", The Nation (13 December 1999)

- Today the changes that are generating enormous inequality, progressively destroying "real jobs" with security and benefits, demanding longer and longer hours and at least two incomes per household as prerequisites for a minimally middle-class existence, and depriving people of control over their work even in the professional classes are taking place in the absence of any credible opposition to the free-market dogma that rules the day. On the contrary, the capitalist triumphalists are riding high on a wave of "prosperity" that has enriched a minority of the population while obscuring the long-term slippage of our standard of living and our quality of life.

- "How Now, Iron Johns?", The Nation (13 December 1999)

- More and more I am coming to the conviction that Roe vs. Wade, in the guise of a great victory, has been in some respects a disaster for feminism. We might be better off today if it had never happened, and we had had to continue a state-by-state political fight. Roe vs. Wade resulted in a lot of women declaring victory and going home. In the meantime we have been losing abortion rights on the ground, both in terms of access and funding and on the ideological and psychological levels.

- "Vote for Ralph Nader!", Salon (6 November 2000)

- A genuinely democratic society requires a secular ethos: one that does not equate morality with religion, stigmatize atheists, defer to religious interests and aims over others or make religious belief an informal qualification for public office. Of course, secularism in the latter sense is not mandated by the First Amendment. It's a matter of sensibility, not law.

- If believers feel that their faith is trivialized and their true selves compromised by a society that will not give religious imperatives special weight, their problem is not that secularists are antidemocratic but that democracy is antiabsolutist.

- "Freedom from Religion" in The Nation (19 February 2001)

- For democrats, it's as crucial to defend secular culture as to preserve secular law. And in fact the two projects are inseparable: When religion defines morality, the wall between church and state comes to be seen as immoral.

- "Freedom from Religion," The Nation (19 February 2001)

- In its original literal sense, "moral relativism" is simply moral complexity. That is, anyone who agrees that stealing a loaf of bread to feed one's children is not the moral equivalent of, say, shoplifting a dress for the fun of it, is a relativist of sorts. But in recent years, conservatives bent on reinstating an essentially religious vocabulary of absolute good and evil as the only legitimate framework for discussing social values have redefined "relative" as "arbitrary." That conflation has been reinforced by social theorists and advocates of identity politics who argue that there is no universal morality, only the value systems of particular cultures and power structures. From this perspective, the psychoanalytic – and by extension the psychotherapeutic – worldview is not relativist at all. Its values are honesty, self-knowledge, assumption of responsibility for the whole of what one does, freedom from inherited codes of family, church, tribe in favor of a universal humanism: in other words, the values of the Enlightenment, as revised and expanded by Freud's critique of scientific rationalism for ignoring the power of unconscious desire.

- The Democratic power elite on some level feels delegitimized by its working-class, black and female constituencies. What it wants are the "legitimate" votes of suburban, white, middle-class, affluent males. Even liberal voters and organizations tend on some tacit level to accept the idea that they are not the "real" Americans the Democrats must pursue.

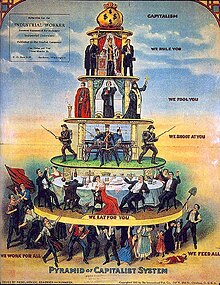

- A triumphalist corporate capitalism, free at last of the specter of Communism, has mobilized its economic power to relentlessly marginalize all nonmarket values; to subordinate every aspect of American life to corporate "efficiency" and the bottom line; to demonize not only government but the very idea of public service and public goods.

- "Dreaming of War", The Nation (15 October 2001)

- The notion that there might be any need for, or possibility of, profound changes in the institutions that shape American life work, family, technology, the primacy of the car and the single-family house — is foreign to the mainstream media that define our common sense. And so conflicts that cannot be addressed politically have expressed themselves by other means. From public psychodramas like the O. J. Simpson trial, the Lewinsky scandal and Columbine to disaster movies, talk shows and "reality TV," popular culture carries the burden of our emotions about race, feminism, sexual morality, youth culture, wealth, competition, exclusion, a physical and social environment that feels out of control.

- "Dreaming of War," The Nation (15 October 2001)

- For a decade Americans have been steeped in the rhetoric of "zero tolerance" and the faith that virtually all problems from drug addiction to lousy teaching can be solved by pouring on the punishment. Even without a Commander in Chief who pledges to rid the world of evildoers, smoke them out of their holes and the like, we would be vulnerable to the temptation to brush aside frustrating complexities and relieve intolerable fear (at least for the moment) by settling on one or more scapegoats to crush. To imagine that trauma casts out fantasy is a dangerous mistake.

- "Dreaming of War," The Nation (15 October 2001)

- The will to power is the will to ecstasy is the will to surrender is the will to submit and, in extremis, to die. Or to put it another way, the rage to attain a freedom and happiness one's psyche cannot accept creates enormous anxiety and ends in self-punishing despair.

- Review of Terror and Liberalism by Paul Berman, Salon (25 March 2003)

- Can the high level of violence in patriarchal cultures be attributed to people's chronic, if largely unconscious, rage over the denial of their freedom and pleasure? To what extent is sanctioned or officially condoned violence — from war and capital punishment to lynching, wife-beating and the rape of "bad" women to harsh penalties for "immoral" activities like drug-taking and nonmarital sex to the religious and ideological persecution of totalitarian states — in effect a socially approved outlet for expressing that rage, as well as a way of relieving guilt by projecting one's own unacceptable desires onto scapegoats?

- In practice, attempts to sort out good erotica from bad porn inevitably comes down to "What turns me on is erotic; what turns you on is pornographic."

- I believe in the separation of sex and state. I also believe that social benefits like health insurance should not be privileges bestowed by marital status but should be available to all as individuals. Marriage, in the sense of a ceremonial commitment of people to merge their lives, is properly a social ritual reflecting religious or personal conviction, and should not have legal status. "Sanctity" is a religious category that is, or ought to be, irrelevant to secular law. The purpose of civil unions should be to establish parental rights and responsibilities, grant next-of-kin status for such purposes as medical decisions and insure equity in matters of property distribution and taxes. Such unions should be available to any two — or more — adults, regardless of gender.

- To say that historical conditions made personal life possible, and with it the self-consciousness that allowed psychoanalysis to emerge, is to tell half the story: one also has to consider that the erotic impulse, ever pressing for satisfaction, had something to do with making the history that encouraged its expression.

- "Historical Analysis", Dissent (Winter 2005)

- Individuals bearing witness do not change history; only movements that understand their social world can do that. Movements encourage solidarity; the moral individual is likely, all unwittingly, to do the opposite, for bearing witness is lonely: it breeds feelings of superiority and moralistic anger against those who are not doing the same.

- Individuals bearing witness cannot do the work of social movements, but they can break a corrosive and demoralizing silence.

- "Three Elegies for Susan Sontag," New Politics (Summer 2005), Vol. X, No. 3

- Some conservatives have expressed outrage that the views of professors are at odds with the views of students, as if ideas were entitled to be represented in proportion to their popularity and students were entitled to professors who share their political or social values. One of the more important functions of college — that it exposes young people to ideas and arguments they have not encountered at home — is redefined as a problem.

- "The Pernicious Concept of 'Balance'", The Chronicle of Higher Education (9 September 2005)

- It’s not only corruption that distorts the utopian impulse when it begins to take some specific social shape. The prospect of more freedom stirs anxiety. We want it, but we fear it; it goes against our most deeply ingrained Judeo-Christian definitions of morality and order. At bottom, utopia equals death is a statement about the wages of sin.

- "Ghosts, Fantasies, and Hope" Dissent (Fall 2005)

- Today, anxiety is a first principle of social life, and the right knows how to exploit it. Capital foments the insecurity that impels people to submit to its demands. And yet there are more Americans than ever before who have tasted certain kinds of social freedoms and, whether they admit it or not, don’t want to give them up or deny them to others. From Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the Terri Schiavo case, the public has resisted the right wing’s efforts to close the deal on the culture. Not coincidentally, the cultural debates, however attenuated, still conjure the ghosts of utopia by raising issues of personal autonomy, power, and the right to enjoy rather than slog through life. In telling contrast, the contemporary left has not posed class questions in these terms; on the contrary, it has ceded the language of freedom and pleasure, "opportunity" and "ownership," to the libertarian right.

- "Ghosts, Fantasies, and Hope," Dissent (Fall 2005)

- The public's continuing ambivalence about cultural matters is all the more striking given that the political conversation on these issues has for 30 years been dominated by an aggressive, radical right-wing insurgency that has achieved an influence far out of proportion to its numbers. Its potent secret weapon has been the guilt and anxiety about desire that inform the character of Americans regardless of ideology; appealing to those largely unconscious emotions, the right has disarmed, intimidated, paralyzed its opposition.

- "Escape from Freedom", Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination, Vol 1, No 2 (2006)

- The goal of the right is not to stop abortion but to demonize it, punish it and make it as difficult and traumatic as possible. All this it has accomplished fairly well, even without overturning Roe v. Wade.

- "Escape from Freedom," Situations: Project of the Radical Imagination, Vol 1, No 2 (2006)

- Take back the night? How can women take back the night when they've never had it?

- From a conversation with Alice Echols, quoted by Echols in "Ellen Willis, 1941-2006", The Nation (10 November 2006)

Beginning To See the Light: Pieces of a Decade (1981)

[edit]- My education was dominated by modernist thinkers and artists who taught me that the supreme imperative was courage to face the awful truth, to scorn the soft-minded optimism of religious and secular romantics as well as the corrupt optimism of governments, advertisers, and mechanistic or manipulative revolutionaries. I learned that lesson well (though it came too late to wholly supplant certain critical opposing influences, like comic books and rock-and-roll). Yet the modernists’ once-subversive refusal to be gulled or lulled has long since degenerated into a ritual despair at least as corrupt, soft-minded, and cowardly — not to say smug — as the false cheer it replaced. The terms of the dialectic have reversed: now the subversive task is to affirm an authentic post-modernist optimism that gives full weight to existent horror and possible (or probable) apocalyptic disaster, yet insists — credibly — that we can, well, overcome. The catch is that you have to be an optimist (an American?) in the first place not to dismiss such a project as insane.

- "Tom Wolfe's Failed Optimism" (1977),

- My deepest impulses are optimistic; an attitude that seems to me as spiritually necessary and proper as it is intellectually suspect.

- "Tom Wolfe's Failed Optimism" (1977)

- There are two kinds of sex, classical and baroque. Classical sex is romantic, profound, serious, emotional, moral, mysterious, spontaneous, abandoned, focused on a particular person, and stereotypically feminine. Baroque sex is pop, playful, funny, experimental, conscious, deliberate, amoral, anonymous, focused on sensation for sensation's sake, and stereotypically masculine. The classical mentality taken to an extreme is sentimental and finally puritanical; the baroque mentality taken to an extreme is pornographic and finally obscene. Ideally, a sexual relation ought to create a satisfying tension between the two modes (a baroque idea, particularly if the tension is ironic) or else blend them so well that the distinction disappears (a classical aspiration).

- "Classical and Baroque Sex in Everyday Life" (1979),

Introduction

[edit]- Mass consumption, advertising, and mass art are a corporate Frankenstein; while they reinforce the system, they also undermine it. By continually pushing the message that we have the right to gratification now, consumerism at its most expansive encouraged a demand for fulfillment that could not so easily be contained by products…

- I think the craving for freedom for self-determination, in the most literal sense is a basic impulse that can be suppressed but never eliminated.

- To be anticapitalist is not enough. Socialist regimes have attacked the grosser forms of economic inequality, yet in terms of the larger struggle for freedom, socialism in practice has been, if anything, a devastating counterrevolution against the liberal concept of individual rights.

- The colonized people who have contributed to the enrichment of the capitalist West share neither its prosperity nor its relative freedom. And the imperatives of the marketplace set people against each other; the comforts of middle-class life are bought at the expense of the poor, liberty at the expense of community.

- On one level the sixties revolt was an impressive illustration of Lenin's remark that the capitalist will sell you the rope to hang him with.

- Art that succeeds manages to evade or transcend or turn to its own purposes the strictures imposed on the artist; on the deepest level it is the enemy of authority, as Plato understood. Mass art is no exception.

- it is the longing for happiness that is potentially radical, while the morality of sacrifice is an age-old weapon of rulers. I don't mean to suggest that social revolution can be painless-only that there is no reason to go through the pain if not, finally, to affirm our right to pleasure. In the meantime we have to live our lives, which means living with the contradictions of a system built on the premise that one must continually choose-insofar as one has a choice-to be either an oppressor or a victim. So long as that system exists, our pleasures will be guilty, our suffering self-righteous, our glimpses of freedom ambiguous and elusive.

- as realities get grimmer, the possibilities tend to be forgotten.

No More Nice Girls: Countercultural Essays (1992)

[edit]- one exasperating example of how easy it is to obliterate history is that Betty Friedan can now get away with the outrageous claim that radical feminist "extremism" turned women off and derailed the movement she built. Radical feminism turned women on, by the thousands. ("Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism" 1984)

- I think it makes sense to look on violence as a tragic last resort, to ask of any violent act that it be necessary to prevent physical destruction or soul-destroying violation, and that it be directed as narrowly as possible to those most responsible for the conflict. I'm glad the French resistance used terror against the Germans-and I think our bombing of Dresden was a war crime. (“Ministries of Fear” November 1985)

- the remedy is not to apologize for Rushdie's book, or qualify the protests. It's to keep emphasizing that the struggle against our own brand of fundamentalism is far from won-ask any American librarian, science teacher, or abortion clinic head-and that the virulence of Khomeini's attack on Rushdie reflects, among other things, conflict between fundamentalists and modernists within the Moslem world. (“In Defense of Offense” 1989)

- There were secularists, democrats, liberals, and feminists in Iran before Khomeini killed or exiled them; there are secularists, democrats, liberals, and feminists in other Islamic countries; and there are immigrants like Salman Rushdie, who have voted with their feet for a freer life. Are they all tools of Western imperialism, poisoned by Satan, as the ayatollah would say? (“In Defense of Offense”)

- Most of us felt about the sexual revolution what Gandhi reputedly thought of Western civilization-that it would be a good idea. (“Coming Down Again” 1989)

- The point of drugs, for me, was always the eternal moment when you felt like Jesus's son (and gender be damned); when you found your center, which is another word for sanity or, I assume, sobriety as Faith understands it. But I never found a drug that would guarantee me that moment, or even a more vulgar euphoria: acid, grass, speed, coke, even Quaaludes (I've never tried heroin), all were unpredictable, potentially treacherous, as likely to concentrate anxiety as to blow it away. Context was all-important-set and setting, as they called it in those days. My emotional state, amplified or undercut by the collective emotional atmosphere, made the difference between a good trip, a bad trip, or no trip at all. For me, the ability to get high (I don't mean only on drugs) flourished in the atmosphere of abandon that defined the '60s-that pervasive cultural invitation to leap boundaries, challenge limits, try anything, want everything, overload the senses, let go. (p 232)

Introduction: Identity Crisis

[edit]- For my generation, formed equally by the liberating exuberance of rock and roll and the imperial brutality of Vietnam, the question of where we stood on America was inescapable. Was this nation (it!) the enemy, tyrannical abroad, hopelessly racist at home, and in the process of choking to death on a glut of consumer goods? Or were we (we!), however corrupted by various forms of power, still the source of a vital democratic impulse that fed cultural dissidence and subverted authoritarian values all over the world? I took the latter position, and through the '6os and '7os, exploring its paradoxes was a central concern of my writing.

- the cultural right has redefined the American project as closing the frontier. Frustrated that their political power has not translated into cultural hegemony, conservatives are methodically attacking cultural institutions-particularly the universities and the arts--Ostensibly for being subverted by radicals, but actually for their persistent liberalism, especially that mushy pluralistic habit of allowing cultural dissidents on the premises. The right, very simply, wants us out of America's public life: the First Amendment may protect our right to rant, but only if we can do it without money and without space.

- Though self-definition is the necessary starting point for any liberation movement, it can take us only so far. The most obvious drawback of identity politics is its logic of fragmentation into ever smaller and more particularist groups: the fracturing of the radical feminist movement along class and gay-straight lines (the racial divide having kept most black women out of the movement to begin with) is the sobering paradigm. What's at stake here, however, is not only the pragmatic question (crucial as it is) of how to avoid being divided and conquered, but our understanding of what it means to be a principled radical...Almost from the beginning, second wave feminism was a study in the limits of the identity politics it did so much to promote.

- radicals need to recreate a politics that emphasizes our common humanity, to base our social theory and practice on principles that apply to us all.

Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

[edit]Preface: The Majoritarian Fallacy

[edit]- American left politics, when successful, has generally worked this way: as radical ideas gain currency beyond their original advocates, they mutate into multiple forms. Groups representing different class, racial, ethnic, political, and cultural constituencies respond to the new movement with varying degrees of support or criticism and end up adapting its ideas to their own agendas. With these modifications, the movement's popularity spreads, putting pressure on existing power relations. Liberal reformers then mediate the process of dilution, containment, and "co-optation" whereby radical ideas that won't go away are incorporated into the system through new laws, policies, and court decisions. The essential dynamic here is a good cop/bad cop routine in which the liberals dismiss the radicals as impractical sectarian extremists, promote their own "responsible" proposals as an alternative, and take the credit for whatever change results. The good news is that this process does bring about significant change. The bad news is that by denying the legitimacy of radicalism it misleads people about how change takes place, rewrites history, and obliterates memory. It also leaves people sadly unprepared for the inevitable backlash. Once the radicals who were a real threat to the existing order have been marginalized, the right sees its opportunity to fight back. Conservatives in their turn become the insurgent minority, winning support by appealing to the still potent influence of the old "reality," decrying the tensions and disruptions that accompany social change, and promoting their own vision of prosperity and social order. Instead of seriously contesting their ideas, liberals try to placate them and cut deals, which only incites them to push further. Desperate to avoid isolation, the liberal left keeps retreating, moving its goal post toward the center, where "ordinary people" supposedly reside; but as yesterday's center becomes today's left, the entire debate shifts to the right. And in the end, despite all their efforts to stay "relevant," the liberals are themselves hopelessly marginalized. This has been our sorry situation since 1994.

- No mass left-wing movement has ever been built on a majoritarian strategy. On the contrary, every such movement-socialism, populism, labor, civil rights, feminism, gay rights, ecology-has begun with a visionary minority whose ideas were at first decried as impractical, ridiculous, crazy, dangerous, and/or immoral.

- Recognizing that “reality” is not inevitable makes it more painful; subversive thoughts provoke the urge to subversive action. But such action has consequences-rebels risk losing their jobs, failing in school, incurring the wrath of parents and spouses, suffering social ostracism. Often vociferous conservatism is sheer defensiveness: people are afraid to be suckers, to get their hopes up, to rethink their hard-won adjustments, to be branded bad or crazy.

- The perceived conflict between class and cultural politics arises not because they are intrinsically incompatible but because majoritarian leftists have uncritically equated the cultural values of workers and "ordinary people" with their historically dominant voices: white, straight, male, and morally conservative.

- the weight of my experience leads me to suspect that in my desire for a freer, saner, and more pleasurable way of life, I am not so different from most people, American or otherwise, as it might presently appear. It is this hopeful suspicion that keeps me writing.

Quotes about Willis

[edit]- In the 1980s, Ellen Willis led the so-called pro-sex radical feminists in their heated challenge to the antipornography movement. Countering the arguments of Andrea Dworkin, Catharine MacKinnon, and others that "sexual liberation is a male supremacist plot, Willis proclaimed that sexual liberation was the keystone of broader social and cultural change.

- Joyce Antler Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement (2020)

- Ellen Willis is the single most important exponent of cultural radicalism in America today. I agree with her; I disagree with her; I am always stimulated.

- Paul Berman blurb for Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

- One of the last times I saw Ellen, she gave me a copy of Beginning to See the Light, with an inscription on the title page. It reads “To sex, hope, and rock and roll and whatever that means today.” The modesty of this simple quote is indicative of the breadth of her influence as a writer. She knew what sex, hope and rock and roll was today, but she wanted me to find out for myself.

- Her essays combine passion and moral clarity, anger and a steady commitment to having fun. Best of all, she channels the secret ecstatic undercurrents of late twentieth century American popular culture, which we need now more than ever.

- Barbara Ehrenreich blurb for The Essential Ellen Willis (2014)

- The name Ellen Willis is synonymous with political intelligence. Her cultural criticism is lucid, unerring, and important. The down-to-earth logic with which she argues a left-libertarian position is, in the final analysis, something visionary.

- J. Hoberman blurb for Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

- Ellen Willis has always been one of the sharpest political writers on the left...one of the most profound as well.

- Katha Pollitt blurb for Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

- Through brilliant, often polemical, writings, the feminist and educator Ellen Willis, who has died of lung cancer aged 64, was central to the cultural debates and political controversies of the United States over nearly four decades...Willis brought lucidity and style to the most controversial and baffling cultural issues—her thought was a beacon of clarity. For those of us fortunate enough to have been her comrades, anticipating her insights was part of what kept us returning to meetings month after month, year after year.

- Alix Kates Shulman remembrance for Jewish Women's Archive

- Like other eminent polemical writers, Willis has always had the knack of turning radical ideas into common sense.

- Andrew Ross blurb for Don't Think, Smile!: Notes on a Decade of Denial (1999)

- Ellen Willis was one of the few great critics of her generation. She was theoretically sophisticated, historically informed, and courageous in her commitment to freedom. Her prose was lyrical and melodic, and she was always unsettling!

- Cornel West blurb for The Essential Ellen Willis (2014)

- Fearless, sweet reason, exacting style, and an unbounded sensuous spirit make Ellen Willis's radical essays among the finest that America has ever produced.

- Sean Wilentz blurb for The Essential Ellen Willis (2014)

External links

[edit]- Ellen Willis online archives

- "Ellen Willis, 64, Journalist and Feminist, Dies" by Margalit Fox, New York Times (10 November 2006)

- "A Remembrance of Ellen Willis" by Susie Linfield, Dissent (Winter 2007)

- "Ellen Willis, 1941-2006", The Nation (10 November 2006)

- "Ellen Willis, 64; radical critic targeted foibles wherever she saw them, on the left or right" by Jocelyn Y. Stewart, Los Angeles Times (15 November 2006)

- "Remembering Ellen Willis, Rock 'n' Roll Feminist Superhero" by Suzy Hansen, New York Observer (20 November 2006)

- "Ellen Willis, 1942-2006" by Judith Levine, Seven Days (22 November 2006)

- "My Ellen Willis" by Michael Bronski, The Boston Phoenix (30 November 2006)

- "Sex, Hope and Rock and Roll: A Conversation with Ellen Willis" by Chris O'Connell, Pop Matters (8 January 2007)

- "Ellen Willis Remembered" The Common Ills (11 November 2006)

- Ellen Willis links at NYU

- Essays by Ellen Willis

- "We Remember Ellen Willis", Dissent (Fall 2006)

- "Ellen Willis's Reply" (1968)

- "Women and the Myth of Consumerism", Ramparts (1969)

- "Hell No, I Won't Go: End the War on Drugs", Village Voice (19 September 1989)

- "We Need a Radical Left", The Nation (29 June 1998)

- "Monica and Barbara and Primal Concerns", New York Times (14 March 1999)

- "Vote for Ralph Nader!", Salon (6 November 2000)

- "The Democrats and Left Masochism", New Politics #31 (new series) (Summer 2001)

- "Can Marriage Be Saved?: A Forum" (II), The Nation (17 June 2004)

- "The Pernicious Concept of 'Balance'", The Chronicle of Higher Education (9 September 2005)

- "Commentary on Maxine Greene's The Dialectic of Freedom"

- Reviews and critiques of Ellen Willis

- Review of Beginning to See the Light by Liza Featherstone, The Nation (8 August 2002)

- Review of Don't Think, Smile! by Eugene McCarraher, Commonweal (22 October 1999)

- Review of Don't Think, Smile! and interview with Ellen Willis by Michael Bronski, Weekly Wire (29 November 1999)

- Review of Don't Think, Smile! by Marcy Sheiner, San Francisco Bay Guardian, (29 March 2000)

- Bully in the Pulpit?, a discussion of "Freedom From Religion" by Ellen Willis in The Nation (22 February 2001)

- "Open Letter to Ellen Willis" by Louis Proyect, PEN-L (internet mailing list) (25 March 2003)

- Interviews

- "Ellen Willis, Feminist and Writer", Fresh Air (14 February 1989)

- Interview with Ellen Willis and others on Implicating Empire by Doug Henwood, Left Business Observer (radio) (27 March 2003)