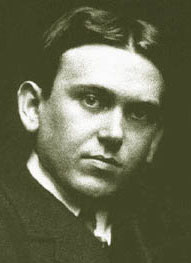

H. L. Mencken

(Redirected from H.L. Mencken)

Henry Louis Mencken (12 September 1880 – 29 January 1956), known as H. L. Mencken, was a twentieth-century journalist, satirist, social critic, cynic, and freethinker, known as the "Sage of Baltimore" and the "American Nietzsche". He is often regarded as one of the most influential American writers of the early 20th century.

- See also:

Quotes[edit]

1900s[edit]

- School teachers, taking them by and large, are probably the most ignorant and stupid class of men in the whole group of mental workers.

- The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1908), pg. 217

- It was morality that burned the books of the ancient sages, and morality that halted the free inquiry of the Golden Age and substituted for it the credulous imbecility of the Age of Faith. It was a fixed moral code and a fixed theology which robbed the human race of a thousand years by wasting them upon alchemy, heretic-burning, witchcraft and sacerdotalism.

- The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1908/1913)

1910s[edit]

- Explanations exist; they have existed for all time; there is always a well-known solution to every human problem — neat, plausible, and wrong.

- "The Divine Afflatus" in New York Evening Mail (16 November 1917); later published in Prejudices: Second Series (1920) and A Mencken Chrestomathy (1949)

- The portion after the second semicolon is widely paraphrased or misquoted. Two examples are "For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong" and "There is always an easy solution to every human problem -- neat, plausible, and wrong."

- Civilization, in fact, grows more and more maudlin and hysterical; especially under democracy it tends to degenerate into a mere combat of crazes; the whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed (and hence clamorous to be led to safety) by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, most of them imaginary.

- In Defense of Women (1918)

- The final test of truth is ridicule. Very few dogmas have ever faced it and survived. Huxley laughed the devils out of the Gadarene swine. Not the laws of the United States but the mother-in-law joke brought the Mormons to surrender. Not the horror of it but the absurdity of it killed the doctrine of infant damnation. But the razor edge of ridicule is turned by the tough hide of truth. How loudly the barber-surgeons laughed at Huxley—and how vainly! What clown ever brought down the house like Galileo? Or Columbus? Or Darwin? . . . They are laughing at Nietzsche yet . . .

- "On Truth" in Damn! A Book of Calumny (1918), p. 53

- No healthy man, in his secret heart, is content with his destiny. He is tortured by dreams and images as a child is tortured by the thought of a state of existence in which it would live in a candy store and have two stomachs.

- The Art Eternal, New York Evening Mail (1918)

Smart Set (1910s)[edit]

- If there is one mental vice, indeed, which sets off the American people from all other folks who walk the earth ... it is that of assuming that every human act must be either right or wrong, and that ninety-nine percent of them are wrong.

- "The American: His New Puritanism," The Smart Set (February 1914)

- An idealist is one who, on noticing that a rose smells better than a cabbage, concludes that it is also more nourishing.

- "A Few Pages of Notes," The Smart Set (January 1915); later published in A Little Book in C Major (1916)

- The allurement that [women] hold out to men is precisely the allurement that Cape Hatteras holds out to sailors: they are enormously dangerous and hence enormously fascinating.

- "The Incomparable Buzzsaw", The Smart Set, May 1919; later published in Prejudices: Second Series, Ch. 10 (1920)

- Women have a hard time of it in this world. They are oppressed by man-made laws, man-made social customs, masculine egoism, the delusion of masculine superiority. Their one comfort is the assurance that, even though it may be impossible to prevail against man, it is always possible to enslave and torture a man.

- "Duty Before Security", The Smart Set, June 1919

- "The Incomparable Buzzsaw", Prejudices: Second Series, Ch. 10 (1920)

- The bitter, of course, goes with the sweet. To be an American is, unquestionably, to be the noblest, grandest, the proudest mammal that ever hoofed the verdure of God's green footstool. Often, in the black abysm of the night, the thought that I am one awakens me with a blast of trumpets, and I am thrown into a cold sweat by contemplation of the fact. I shall cherish it on the scaffold; it will console me in Hell. But there is no perfection under Heaven, so even an American has his small blemishes, his scarcely discernible weaknesses, his minute traces of vice and depravity.

- The Smart Set (October 1919), p. 140 [1]

- Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.

- "A Few Pages of Notes," The Smart Set (January 1915); later published in A Little Book in C major (1916), and A Mencken Crestomathy (1949)

A Book of Burlesques (1916)[edit]

- Of all escape mechanisms, death is the most efficient.

- A Book of Burlesques (1916)

- It is a fact that no man improves much after the age of 60 and after 65, most suffer a really alarming decline. I could give some examples, but at the advice of my publisher will refrain from doing so.

- A Book of Burlesques (1916)

- Progress: The process whereby the human race has got rid of whiskers, the vermiform appendix and God.

- A Book of Burlesques (1916)

A Little Book in C Major (1916)[edit]

- Socialism is the theory that the desire of one man to get something he hasn't got is more pleasing to a just God than the desire of some other man to keep what he has got.

- A Little Book in C Major, New York, NY, John Lane Company (1916) p. 51

- The objection to Puritans is not that they try to make us think as they do, but that they try to make us do as they think.

- A Little Book in C Major, New York, NY, John Lane Company (1916) p. 53

- At the bottom of Puritanism one finds envy of the fellow who is having a better time in the world, and hence hatred of him. At the bottom of democracy one finds the same thing. This is why all Puritans are democrats and all democrats are Puritans.

- A Little Book in C Major, New York, NY, John Lane Company (1916) p. 76

- Truth would quickly cease to be stranger than fiction, once we got used to it.

- A Little Book in C Major (1916)

- Bachelors know more about women than married men. If they didn't, they'd be married, too.

- A Little Book in C major (1916) ; later published in A Mencken Crestomathy (1949)

A Book of Prefaces (1917)[edit]

- The virulence of the national appetite for bogus revelation.

- Ch. 1

- To the man with an ear for verbal delicacies — the man who searches painfully for the perfect word, and puts the way of saying a thing above the thing said — there is in writing the constant joy of sudden discovery, of happy accident.

- Ch. 2

- Poverty is a soft pedal upon the branches of human activity, not excepting the spiritual.

- Ch. 4

- Time is the great legalizer, even in the field of morals.

- Ch. 4

Prejudices, First Series (1919)[edit]

- I was at the job of reading it for days and days, endlessly daunted and halted by its laborious dullness, its flatulent fatuity, its almost fabulous inconsequentiality. (On H. G. Wells' Joan and Peter) Ch. 2, "The Late Mr. Wells"

- The public...demands certainties...But there are no certainties.

- Ch. 3

- Every normal man must be tempted, at times, to spit upon his hands, hoist the black flag, and begin slitting throats.

- Ch. 6, "The New Poetry Movement" [1]

- All successful newspapers are ceaselessly querulous and bellicose. They never defend anyone or anything if they can help it; if the job is forced on them, they tackle it by denouncing someone or something else.

- Ch. 13

- The great artists of the world are never Puritans, and seldom even ordinarily respectable. No virtuous man — that is, virtuous in the Y.M.C.A. sense — has ever painted a picture worth looking at, or written a symphony worth hearing, or a book worth reading.

- Ch. 16

- To be in love is merely to be in a state of perpetual anesthesia — to mistake an ordinary young man for a Greek god or an ordinary young woman for a goddess.

- Ch. 16

- To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble. But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true!

- ?Ch. ??

The American Language (1919)[edit]

- A novelty loses nothing by the fact that it is a novelty; it rather gains something, and particularly if it meets the national fancy for the terse, the vivid, and, above all, the bold and imaginative.

- Ch. 5

- Philadelphia is the most pecksniffian of American cities, and thus probably leads the world.

1920s[edit]

The Presidency tends, year by year, to go to such men. As democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart's desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.

- Off goes the head of the king, and tyranny gives way to freedom. The change seems abysmal. Then, bit by bit, the face of freedom hardens, and by and by it is the old face of tyranny. Then another cycle, and another. But under the play of all these opposites there is something fundamental and permanent — the basic delusion that men may be governed and yet be free.

- Preface to the first edition of The American Credo : A Contribution Toward the Interpretation of the National Mind (1920)

- The American of today, in fact, probably enjoys less personal liberty than any other man of Christendom, and even his political liberty is fast succumbing to the new dogma that certain theories of government are virtuous and lawful, and others abhorrent and felonious. Laws limiting the radius of his free activity multiply year by year: It is now practically impossible for him to exhibit anything describable as genuine individuality, either in action or in thought, without running afoul of some harsh and unintelligible penalty. It would surprise no impartial observer if the motto "In God we trust" were one day expunged from the coins of the republic by the Junkers at Washington, and the far more appropriate word, "verboten," substituted. Nor would it astound any save the most romantic if, at the same time, the goddess of liberty were taken off the silver dollars to make room for a bas-relief of a policeman in a spiked helmet. Moreover, this gradual (and, of late, rapidly progressive) decay of freedom goes almost without challenge; the American has grown so accustomed to the denial of his constitutional rights and to the minute regulation of his conduct by swarms of spies, letter-openers, informers and agents provocateurs that he no longer makes any serious protest.

- The American Credo: A Contribution toward the Interpretation of the National Mind (1920)

- The American is marked, in fact, by precisely the habits of mind and act that one would look for in a man insatiably ambitious and yet incurably fearful, to wit, the habits, on the one hand, of unpleasant assertiveness, of somewhat boisterous braggardism, of incessant pushing, and, on the other hand, of conformity, caution and subservience. He is forever talking of his rights as if he stood ready to defend them with his last drop of blood, and forever yielding them up at the first demand.

- The American Credo: A Contribution toward the Interpretation of the National Mind (1920)

- It is the dull man who is always sure, and the sure man who is always dull.

- Prejudices, Second Series (1920) Ch. 1

- How does so much [false news] get into the American newspapers, even the good ones? Is it because journalists, as a class, are habitual liars, and prefer what is not true to what is true? I don't think it is. Rather, it is because journalists are, in the main, extremely stupid, sentimental and credulous fellows -- because nothing is easier than to fool them -- because the majority of them lack the sharp intelligence that the proper discharge of their duties demands.

- Prejudices: A Selection, p. 220

- All of us, if we are of reflective habit, like and admire men whose fundamental beliefs differ radically from our own. But when a candidate for public office faces the voters he does not face men of sense; he faces a mob of men whose chief distinguishing mark is the fact that they are quite incapable of weighing ideas, or even of comprehending any save the most elemental — men whose whole thinking is done in terms of emotion, and whose dominant emotion is dread of what they cannot understand. So confronted, the candidate must either bark with the pack or count himself lost. ... All the odds are on the man who is, intrinsically, the most devious and mediocre — the man who can most adeptly disperse the notion that his mind is a virtual vacuum.

The Presidency tends, year by year, to go to such men. As democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart's desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.- Bayard vs. Lionheart, The Evening Sun, Baltimore (26 July 1920), newspapers.com/clip

- The only good bureaucrat is one with a pistol at his head. Put it in his hand and it's good-bye to the Bill of Rights.

- On Politics: A Carnival of Buncombe (1920-1936), p. 279

- To sum up: 1. The cosmos is a gigantic fly-wheel making 10,000 revolutions a minute. 2. Man is a sick fly taking a dizzy ride on it. 3. Religion is the theory that the wheel was designed and set spinning to give him the ride.

- "Coda" from Smart Set (December 1920)

- If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.

- "Epitaph" from Smart Set (December 1921)

- All government, in its essence, is a conspiracy against the superior man: its one permanent object is to oppress him and cripple him. If it be aristocratic in organization, then it seeks to protect the man who is superior only in law against the man who is superior in fact; if it be democratic, then it seeks to protect the man who is inferior in every way against both. One of its primary functions is to regiment men by force, to make them as much alike as possible and as dependent upon one another as possible, to search out and combat originality among them. All it can see in an original idea is potential change, and hence an invasion of its prerogatives. The most dangerous man to any government is the man who is able to think things out for himself, without regard to the prevailing superstitions and taboos. Almost inevitably he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane and intolerable, and so, if he is romantic, he tries to change it. And even if he is not romantic personally he is very apt to spread discontent among those who are.

- "Le Contrat Social", in: Prejudices: Third Series (1922)

- To be happy one must be (a) well fed, unhounded by sordid cares, at ease in Zion, (b) full of a comfortable feeling of superiority to the masses of one's fellow men, and (c) delicately and unceasingly amused according to one's taste. It is my contention that, if this definition be accepted, there is no country in the world wherein a man constituted as I am — a man of my peculiar weakness, vanities, appetites, and aversions — can be so happy as he can be in the United States.

- On Being An American (1922)

- When I mount the scaffold at last these will be my farewell words to the sheriff: Say what you will against me when I am gone, but don't forget to add, in common justice, that I was never converted to anything.

- Baltimore Evening Sun (12 June 1922)

- The men the American people admire most extravagantly are the most daring liars; the men they detest most violently are those who try to tell them the truth. A Galileo could no more be elected President of the United States than he could be elected Pope of Rome.

- H.L. Menken & George Jean Nathan, The Smart Set (1922)

- The Quote Investigator provides evidence that that these are Menken's words.

- My literary theory, like my politics, is based chiefly upon one idea, to wit, the idea of freedom. I am, in belief, a libertarian of the most extreme variety.

- Letter to George Müller (1923), Marion Elizabeth Rodgers, Mencken: The American Iconoclast, Oxford University Press, (2005) pp. 105-106, first published in Autobiographical Notes, 1941

- The fact is that the average man's love of liberty is nine-tenths imaginary, exactly like his love of sense, justice and truth. He is not actually happy when free; he is uncomfortable, a bit alarmed, and intolerably lonely. Liberty is not a thing for the great masses of men. It is the exclusive possession of a small and disreputable minority, like knowledge, courage and honor. It takes a special sort of man to understand and enjoy liberty — and he is usually an outlaw in democratic societies.

- Baltimore Evening Sun (12 February 1923)

- Critical note.—Of a piece with the absurd pedagogical demand for so-called constructive criticism is the doctrine that an iconoclast is a hollow and evil fellow unless he can prove his case. Why, indeed, should he prove it? Is he judge, jury, prosecuting officer, hangman? He proves enough, indeed, when he proves by his blasphemy that this or that idol is defectively convincing—that at least one visitor to the shrine is left full of doubts. The fact is enormously significant; it indicates that instinct has somehow risen superior to the shallowness of logic, the refuge of fools. The pedant and the priest have always been the most expert of logicians—and the most diligent disseminators of nonsense and worse. The liberation of the human mind has never been furthered by dunderheads; it has been furthered by gay fellows who heaved dead cats into sanctuaries and then went roistering down the highways of the world, proving to all men that doubt, after all, was safe—that the god in the sanctuary was finite in his power and hence a fraud. One horse-laugh is worth ten thousand syllogisms. It is not only more effective; it is also vastly more intelligent.

- "Clinical Notes" in The American Mercury (January 1924), p. 75; also in Prejudices, Fourth Series (1924)

- The difference between a moral man and a man of honor is that the latter regrets a discreditable act, even when it has worked and he has not been caught.

- Prejudices, Fourth Series, ch. 11 (1924)

- What is any political campaign save a concerted effort to turn out a set of politicians who are admittedly bad and put in a set who are thought to be better. The former assumption, I believe is always sound; the latter is just as certainly false. For if experience teaches us anything at all it teaches us this: that a good politician, under democracy, is quite as unthinkable as an honest burglar.

- Prejudices, Fourth Series (1924)

- Suppose two-thirds of the members of the national House of Representatives were dumped into the Washington garbage incinerator tomorrow, what would we lose to offset our gain of their salaries and the salaries of their parasites?

- Prejudices, Fourth Series (1924)

- The strange American ardor for passing laws, the insane belief in regulation and punishment, plays into the hands of the reformers, most of them quacks themselves. Their efforts, even when honest, seldom accomplish any appreciable good. The Harrison Act, despite its cruel provisions, has not diminished drug addiction in the slightest. The Mormons, after years of persecution, are still Mormons, and one of them is now a power in the Senate. Socialism in the United States was not laid by the Espionage Act; it was laid by the fact that the socialists, during the war, got their fair share of the loot. Nor was the stately progress of osteopathy and chiropractic halted by the early efforts to put them down. Oppressive laws do not destroy minorities; they simply make bootleggers.

- Editorial in The American Mercury (May 1924), p. 26

- I propose that it shall be no longer malum in se for a citizen to pummel, cowhide, kick, gouge, cut, wound, bruise, maim, burn, club, bastinado, flay, or even lynch a [government] jobholder, and that it shall be malum prohibitum only to the extent that the punishment exceeds the jobholder's deserts. The amount of this excess, if any, may be determined very conveniently by a petit jury, as other questions of guilt are now determined. The flogged judge, or Congressman, or other jobholder, on being discharged from hospital — or his chief heir, in case he has perished — goes before a grand jury and makes a complaint, and, if a true bill is found, a petit jury is empaneled and all the evidence is put before it. If it decides that the jobholder deserves the punishment inflicted upon him, the citizen who inflicted it is acquitted with honor. If, on the contrary, it decides that this punishment was excessive, then the citizen is adjudged guilty of assault, mayhem, murder, or whatever it is, in a degree apportioned to the difference between what the jobholder deserved and what he got, and punishment for that excess follows in the usual course.

- "The Malevolent Jobholder," The American Mercury (June 1924), p. 156

- This preposterous quackery flourishes lushly in the back reaches of the Republic, and begins to conquer the less civilized folk of the big cities. As the oldtime family doctor dies out in the country towns, with no competent successor willing to take over his dismal business, he is followed by some hearty blacksmith or ice-wagon driver, turned into a chiropractor in six months, often by correspondence. In Los Angeles the Damned there are probably more chiropractors than actual physicians, and they are far more generally esteemed. Proceeding from the Ambassador Hotel to the heart of the town, along Wilshire Boulevard, one passes scores of their gaudy signs; there are even many chiropractic "hospitals." The morons who pour in from the prairies and deserts, most of them ailing, patronize these "hospitals" copiously, and give to the chiropractic pathology the same high respect that they accord to the theology of the town sorcerers. That pathology is grounded upon the doctrine that all human ills are caused by the pressure of misplaced vertebrae upon the nerves which come out of the spinal cord—in other words, that every disease is the result of a pinch. This, plainly enough, is buncombe. The chiropractic therapeutics rest upon the doctrine that the way to get rid of such pinches is to climb upon a table and submit to a heroic pummeling by a retired piano-mover. This, obviously, is buncombe doubly damned.

- "Chiropractic" in Baltimore Evening Sun (December 1924)

- Do they believe that the aim of teaching English is to increase the exact and beautiful use of the language? Or that it is to inculcate and augment patriotism? Or that it is to diminish sorrow in the home? Or that it has some other end, cultural, economic, or military? ... it was their verdict by a solemn referendum that the principal objective in teaching English was to make good spellers, and that after that came the breeding of good capitalizers. ... I have maintained for years, sometimes perhaps with undue heat: that pedagogy in the United States is fast descending to the estate of a childish necromancy, and that the worst idiots, even among pedagogues, are the teachers of English. It is positively dreadful to think that the young of the American species are exposed day in and day out to the contamination of such dark minds. What can be expected of education that is carried on in the very sewers of the intellect? How can morons teach anything that is worth knowing?

- On "teachers of English" in "The Schoolmarm's Goal" in The Lower Depths (1925)

- Liberty and democracy are eternal enemies, and every one knows it who has ever given any sober reflection to the matter. A democratic state may profess to venerate the name, and even pass laws making it officially sacred, but it simply cannot tolerate the thing. In order to keep any coherence in the governmental process, to prevent the wildest anarchy in thought and act, the government must put limits upon the free play of opinion. In part, it can reach that end by mere propaganda, by the bald force of its authority — that is, by making certain doctrines officially infamous. But in part it must resort to force, i.e., to law. One of the main purposes of laws in a democratic society is to put burdens upon intelligence and reduce it to impotence. Ostensibly, their aim is to penalize anti-social acts; actually their aim is to penalize heretical opinions. At least ninety-five Americans out of every 100 believe that this process is honest and even laudable; it is practically impossible to convince them that there is anything evil in it. In other words, they cannot grasp the concept of liberty. Always they condition it with the doctrine that the state, i.e., the majority, has a sort of right of eminent domain in acts, and even in ideas — that it is perfectly free, whenever it is so disposed, to forbid a man to say what he honestly believes. Whenever his notions show signs of becoming "dangerous," ie, of being heard and attended to, it exercises that prerogative. And the overwhelming majority of citizens believe in supporting it in the outrage. Including especially the Liberals, who pretend — and often quite honestly believe — that they are hot for liberty. They never really are. Deep down in their hearts they know, as good democrats, that liberty would be fatal to democracy — that a government based upon shifting and irrational opinion must keep it within bounds or run a constant risk of disaster. They themselves, as a practical matter, advocate only certain narrow kinds of liberty — liberty, that is, for the persons they happen to favor. The rights of other persons do not seem to interest them. If a law were passed tomorrow taking away the property of a large group of presumably well-to-do persons — say, bondholders of the railroads — without compensation and without even colorable reason, they would not oppose it; they would be in favor of it. The liberty to have and hold property is not one they recognize. They believe only in the liberty to envy, hate and loot the man who has it.

- "Liberty and Democracy" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (13 April 1925), also in A Second Mencken Chrestomathy : New Selections from the Writings of America's Legendary Editor, Critic, and Wit (1994) edited by Terry Teachout, p. 35

- I have seen many theoretical objections to democracy, and sometimes urge them with such heat that it probably goes beyond the bound of sound taste, but I am thoroughly convinced, nonetheless, that the democratic nations are happier than any other. The United States today, indeed, is probably the happiest the world has ever seen. Taxes are high, but they are still well within the means of the taxpayer: he could pay twice as much and still survive. The laws are innumerable and idiotic, but only prisoners in the penitentiaries and persons under religious vows ever obey them. The country is governed by rogues, but there is no general dislike of rogues: on the contrary, they are esteemed and envied. Best of all, the people have the pleasant feeling that they can make improvements at any time they want to— . . . in other words, they are happy. Democrats are always happy. Democracy is a sort of laughing gas. It will not cure anything, perhaps, but it unquestionably stops the pain.

- "The Master Illusion" in the The American Mercury (March 1925), p. 319

- Such obscenities as the forthcoming trial of the Tennessee evolutionist, if they serve no other purpose, at least call attention dramatically to the fact that enlightenment, among mankind, is very narrowly dispersed. It is common to assume that human progress affects everyone-that even the dullest man, in these bright days, knows more than any man of, say, the Eighteenth Century, and is, far more civilized. This assumption is quite erroneous. The man of the educated minority, no doubt, know more than their predecessors, and of some of them, perhaps, it may be said that they are more civilized- though I should not like to be put to giving names, but the great masses of men, even in this inspired republic, are ignorant, they are dishonest, they are cowardly, they are ignoble. They know little if anything that is worth knowing, and there is not the slightest sign of a natural desire among them to increase their knowledge.

- Homo Neanderthalensis Baltimore Sun (June 29th, 1925), The Impossible Mencken

- Every step in human progress, from the first feeble stirrings in the abyss of time, has been opposed by the great majority of men. Every valuable thing that has been added to the store of man's possessions has been derided by them when it was new, and destroyed by them when they had power. They have fought every new truth ever heard of, and they have killed every truth-seeker who got into their hands.

- Homo Neanderthalensis Baltimore Sun (June 29th, 1925), The Impossible Mencken

- It is the national custom to sentimentalize the dead, as it is to sentimentalize men about to be hanged. Perhaps I fall into that weakness here. The Bryan I shall remember is the Bryan of his last weeks on earth -- broken, furious, and infinitely pathetic. It was impossible to meet his hatred with hatred to match it. He was winning a battle that would make him forever infamous wherever enlightened men remembered it and him. Even his old enemy, Darrow, was gentle with him at the end. That cross-examination might have been ten times as devastating. It was plain to everyone that the old Berserker Bryan was gone -- that all that remained of him was a pair of glaring and horrible eyes.

But what of his life? Did he accomplish any useful thing? Was he, in his day, of any dignity as a man, and of any value to his fellow-men? I doubt it. Bryan, at his best, was simply a magnificent job-seeker. The issues that he bawled about usually meant nothing to him. He was ready to abandon them whenever he could make votes by doing so, and to take up new ones at a moment's notice. For years he evaded Prohibition as dangerous; then he embraced it as profitable. At the Democratic National Convention last year he was on both sides, and distrusted by both. In his last great battle there was only a baleful and ridiculous malignancy. If he was pathetic, he was also disgusting.

Bryan was a vulgar and common man, a cad undiluted. He was ignorant, bigoted, self-seeking, blatant and dishonest. His career brought him into contact with the first men of his time; he preferred the company of rustic ignoramuses. It was hard to believe, watching him at Dayton, that he had traveled, that he had been received in civilized societies, that he had been a high officer of state. He seemed only a poor clod like those around him, deluded by a childish theology, full of an almost pathological hatred of all learning, all human dignity, all beauty, all fine and noble things. He was a peasant come home to the dung-pile. Imagine a gentleman, and you have imagined everything that he was not.- "Bryan" in Baltimore Evening Sun (27 July 1925)

- Once more, alas, I find myself unable to follow the best Liberal thought. What the World's contention amounts to, at bottom, is simply the doctrine that a man engaged in combat with superstition should be very polite to superstition. This, I fear, is nonsense. The way to deal with superstition is not to be polite to it, but to tackle it with all arms, and so rout it, cripple it, and make it forever infamous and ridiculous. Is it, perchance, cherished by persons who should know better? Then their folly should be brought out into the light of day, and exhibited there in all its hideousness until they flee from it, hiding their heads in shame.

True enough, even a superstitious man has certain inalienable rights. He has a right to harbor and indulge his imbecilities as long as he pleases, provided only he does not try to inflict them upon other men by force. He has a right to argue for them as eloquently as he can, in season and out of season. He has a right to teach them to his children. But certainly he has no right to be protected against the free criticism of those who do not hold them. . . . They are free to shoot back. But they can't disarm their enemy.

The meaning of religious freedom, I fear, is sometimes greatly misapprehended. It is taken to be a sort of immunity, not merely from governmental control but also from public opinion. A dunderhead gets himself a long-tailed coat, rises behind the sacred desk, and emits such bilge as would gag a Hottentot. Is it to pass unchallenged? If so, then what we have is not religious freedom at all, but the most intolerable and outrageous variety of religious despotism. Any fool, once he is admitted to holy orders, becomes infallible. Any half-wit, by the simple device of ascribing his delusions to revelation, takes on an authority that is denied to all the rest of us. . . . What should be a civilized man's attitude toward such superstitions? It seems to me that the only attitude possible to him is one of contempt. If he admits that they have any intellectual dignity whatever, he admits that he himself has none. If he pretends to a respect for those who believe in them, he pretends falsely, and sinks almost to their level. When he is challenged he must answer honestly, regardless of tender feelings.- "Aftermath" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (14 September 1925)

- By what route do otherwise sane men come to believe such palpable nonsense? How is it possible for a human brain to be divided into two insulated halves, one functioning normally, naturally and even brilliantly, and the other capable only of such ghastly balderdash which issues from the minds of Baptist evangelists? Such balderdash takes various forms, but it is at its worst when it is religious. Why should this be so? What is there in religion that completely flabbergasts the wits of those who believe in it? I see no logical necessity for that flabbergasting. Religion, after all, is nothing but an hypothesis framed to account for what is evidentially unaccounted for. In other fields such hypotheses are common, and yet they do no apparent damage to those who incline to them. But in the religious field they quickly rush the believer to the intellectual Bad Lands. He not only becomes anaesthetic to objective fact; he becomes a violent enemy of objective fact. It annoys and irritates him. He sweeps it away as something somehow evil. . .

- The American Mercury (February 1926)

- Herein lies the value of free speech. It makes concealment difficult, and, in the long run, impossible. One heretic, if he is right, is as good as a host. He is bound to win in the long run. It is thus no wonder that foes of the enlightenment always begin their proceedings by trying to deny free speech to their opponents. It is dangerous to them and they know it. So they have at it by accusing these opponents of all sorts of grave crimes and misdemeanors, most of them clearly absurd – in other words, by calling them names and trying to scare them.

- The Sad Case of Tennessee in the Chicago Tribune (March 14, 1926)

- It is the natural tendency of the ignorant to believe what is not true. In order to overcome that tendency it is not sufficient to exhibit the true; it is also necessary to expose and denounce the false. To admit that the false has any standing in court, that it ought to be handled gently because millions of morons cherish it and thousands of quacks make their livings propagating it—to admit this, as the more fatuous of the reconcilers of science and religion inevitably do, is to abandon a just cause to its enemies, cravenly and without excuse. It is, of course, quite true that there is a region in which science and religion do not conflict. That is the region of the unknowable.

- The American Mercury (May 1926)

- Here is tragedy—and here is America. For the curse of the country, as well of all democracies, is precisely the fact that it treats its best men as enemies. The aim of our society, if it may be said to have an aim, is to iron them out. The ideal American, in the public sense, is a respectable vacuum.

- "More Tips for Novelists" in the Chicago Tribune (2 May 1926)

- The truth, indeed, is something that mankind, for some mysterious reason, instinctively dislikes. Every man who tries to tell it is unpopular, and even when, by the sheer strength of his case, he prevails, he is put down as a scoundrel.

- Chicago Tribune (23 May 1926)

- The basic fact about human existence is not that it is a tragedy, but that it is a bore. It is not so much a war as an endless standing in line. The objection to it is not that it is predominantly painful, but that it is lacking in sense.

- Baltimore Evening Sun (9 August 1926)

- No one in this world, so far as I know—and I have researched the records for years, and employed agents to help me—has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of the plain people. Nor has anyone ever lost public office thereby.

- 'Notes On Journalism' in the Chicago Tribune (19 September 1926)

- The first sentence is often paraphrased as "No one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American people." (The Yale Book of Quotations, 2006, p. 512)

- It is [a politician's] business to get and hold his job at all costs. If he can hold it by lying, he will hold it by lying; if lying peters out, he will try to hold it by embracing new truths. His ear is ever close to the ground.

- Notes on Democracy (1926), Part II, p. 99

- Public opinion, in its raw state, gushes out in the immemorial form of the mob's fear. It is piped into central factories, and there it is flavoured and coloured and put into cans.

- Notes on Democracy (1926)

- I believe that liberty is the only genuinely valuable thing that men have invented, at least in the field of government, in a thousand years. I believe that it is better to be free than to be not free, even when the former is dangerous and the latter safe. I believe that the finest qualities of man can flourish only in free air – that progress made under the shadow of the policeman's club is false progress, and of no permanent value. I believe that any man who takes the liberty of another into his keeping is bound to become a tyrant, and that any man who yields up his liberty, in however slight the measure, is bound to become a slave.

- "Why Liberty?", in the Chicago Tribune (30 January 1927)

- Shave a gorilla and it would be almost impossible, at twenty paces, to distinguish him from a heavyweight champion of the world. Skin a chimpanzee, and it would take an autopsy to prove he was not a theologian.

- Baltimore Evening Sun (4 April 1927)

- No man ever entered the White House under the burden of a more inconvenient past. And no President was ever denounced with greater ferocity. -- said of Andrew Jackson

- Review of Andrew Jackson: An Epic in Homespun by Gerald W. Johnson, The American Mercury, March 1928, pp. 382-383 (March 1928)

- The most curious social convention of the great age in which we live is the one to the effect that religious opinions should be respected. Its evil effects must be plain enough to everyone. All it accomplishes is (a) to throw a veil of sanctity about ideas that violate every intellectual decency, and (b) to make every theologian a sort of chartered libertine. No doubt it is mainly to blame for the appalling slowness with which really sound notions make their way in the world. The minute a new one is launched, in whatever field, some imbecile of a theologian is certain to fall upon it, seeking to put it down. The most effective way to defend it, of course, would be to fall upon the theologian, for the only really workable defense, in polemics as in war, is a vigorous offensive. But the convention that I have mentioned frowns upon that device as indecent, and so theologians continue their assault upon sense without much resistance, and the enlightenment is unpleasantly delayed.

There is, in fact, nothing about religious opinions that entitles them to any more respect than other opinions get. On the contrary, they tend to be noticeably silly. If you doubt it, then ask any pious fellow of your acquaintance to put what he believes into the form of an affidavit, and see how it reads... . "I, John Doe, being duly sworn, do say that I believe that, at death, I shall turn into a vertebrate without substance, having neither weight, extent nor mass, but with all the intellectual powers and bodily sensations of an ordinary mammal; . . . and that, for the high crime and misdemeanor of having kissed my sister-in-law behind the door, with evil intent, I shall be boiled in molten sulphur for one billion calendar years." Or, "I, Mary Roe, having the fear of Hell before me, do solemnly affirm and declare that I believe it was right, just, lawful and decent for the Lord God Jehovah, seeing certain little children of Beth-el laugh at Elisha's bald head, to send a she-bear from the wood, and to instruct, incite, induce and command it to tear forty-two of them to pieces." Or, "I, the Right Rev._____ _________, Bishop of _________,D.D., LL.D., do honestly, faithfully and on my honor as a man and a priest, declare that I believe that Jonah swallowed the whale," or vice versa, as the case may be. No, there is nothing notably dignified about religious ideas. They run, rather, to a peculiarly puerile and tedious kind of nonsense. At their best, they are borrowed from metaphysicians, which is to say, from men who devote their lives to proving that twice two is not always or necessarily four. At their worst, they smell of spiritualism and fortune telling. Nor is there any visible virtue in the men who merchant them professionally. Few theologians know anything that is worth knowing, even about theology, and not many of them are honest. One may forgive a Communist or a Single Taxer on the ground that there is something the matter with his ductless glands, and that a Winter in the south of France would relieve him. But the average theologian is a hearty, red-faced, well-fed fellow with no discernible excuse in pathology. He disseminates his blather, not innocently, like a philosopher, but maliciously, like a politician. In a well-organized world he would be on the stone-pile. But in the world as it exists we are asked to listen to him, not only politely, but even reverently, and with our mouths open.- The American Mercury (March, 1930); first printed, in part, in the Baltimore Evening Sun (9 December 1929)

Prejudices, Third Series (1922)[edit]

- The older I grow the more I distrust the familiar doctrine that age brings wisdom. . . . Certainly it would be difficult to imagine any committee of relatively young men, of thirty or thirty-five, showing the unbroken childishness, ignorance and lack of humor of the Supreme Court of the United States. The average age of the learned justices must be well beyond sixty, and all of them are supposed to be of finished and mellowed sagacity. Yet their knowledge of the most ordinary principles of justice often turns out to be extremely meager, and when they spread themselves grandly upon a great case their reasoning powers are usually found to be precisely equal to those of a respectable Pullman conductor.

- "Advice to Young Men" in Prejudices: Third Series (1922).

- There are no mute, inglorious Miltons, save in the hallucinations of poets. The one sound test of Milton is that he functions as a Milton.

- Ch. 3

- Truth, indeed, is something that is believed in completely only by persons who have never tried personally to pursue it to its fastness and grab it by the tail. It is the adoration of second-rate men — men who always receive it as second-hand. Pedagogues believe in immutable truths and spend their lives trying to determine them and propagate them; the intellectual progress of man consists largely of a concerted effort to block and destroy their enterprise. Nine times out of ten, in the arts as in life, there is actually no truth to be discovered; there is only error to be exposed. In whole departments of human inquiry it seems to me quite unlikely that the truth ever will be discovered. Nevertheless, the rubber-stamp thinking of the world always makes the assumption that the exposure of an error is identical with the discovery of truth — that error and truth are simply opposites. They are nothing of the sort. What the world turns to, when it has been cured of one error, is usually simply another error, and maybe one worse than the first one. This is the whole history of the intellect in brief. The average man of today does not believe in precisely the same imbecilities that the Greek of the Fourth Century before Christ believed in, but the things that he does believe in are often quite as idiotic.

Perhaps this statement is a bit too sweeping. There is, year by year, a gradual accumulation of what may be called, provisionally, truths — there is a slow accretion of ideas that somehow manage to meet all practicable human tests, and so survive. But even so, it is risky to call them absolute truths. All that one may safely say of them is that no one, as yet, has demonstrated that they are errors. Soon or late, if experience teaches us anything, they are likely to succumb too. The profoundest truths of the Middle Ages are now laughed at by schoolboys. The profoundest truths of democracy will be laughed at, a few centuries hence, even by school-teachers.- Ch. 3 "Footnote on Criticism", pp. 85-104

- Upon the low value of "constructive" criticism I can offer testimony out of my own experience. My books have been commonly reviewed at length, and many critics have devoted themselves to pointing out what they conceive to be my errors, both of fact and of taste. Well, I cannot recall a case in which any suggestion offered by a "constructive" critic has helped me in the slightest, or even actively interested me. Every such wet-nurse of letters has sought fatuously to make me write in a way differing from that in which the Lord God Almighty, in His infinite wisdom, impels me to write — that is, to make me write stuff which, coming from me, would be as false as an appearance of decency in a Congressman. All the benefits I have ever got from the critics of my work have come from the destructive variety. A hearty slating always does me good, particularly if it be well written. It begins by enlisting my professional respect; it ends by making me examine my ideas coldly in the privacy of my chamber. Not, of course, that I usually revise them, but I at least examine them. If I decide to hold fast to them, they are all the dearer to me thereafter, and I expound them with a new passion and plausibility. If, on the contrary, I discern holes in them, I shelve them in a pianissimo manner, and set about hatching new ones to take their place. But "constructive" criticism irritates me. I do not object to being denounced, but I can't abide being schoolmastered, especially by men I regard as imbeciles.

- Ch. 3 "Footnote on Criticism", pp. 85-104

- Injustice is relatively easy to bear; what stings is justice.

- Ch. 3

- The older I grow the more I distrust the familiar doctrine that age brings wisdom.

- Ch. 3

- The Gettysburg speech was at once the shortest and the most famous oration in American history... But let us not forget that it is poetry, not logic; beauty, not sense. Think of the argument in it! Put it into the cold words of everyday! The doctrine is simply this: that the Union soldiers who died at Gettysburg sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination – "that government of the people, by the people, for the people, should not perish from the earth". It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in the battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves.

- Ch. 8

- Faith may be defined briefly as an illogical belief in the occurrence of the improbable.

- Ch. 14 "Types of Men" - 3 : The Believer

- A man full of faith is simply one who has lost (or never had) the capacity for clear and realistic thought. He is not a mere ass; he is actually ill. Worse, he is incurable, for disappointment, being essentially an objective phenomenon, cannot permanently affect his subjective infirmity. His faith takes on the virulence of a chronic infection. What he usually says, in substance, is this: "Let us trust in God, who has always fooled us in the past.

- Ch. 14 "Types of Men" - 3 : The Believer

- The professor must be an obscurantist or he is nothing; he has a special and unmatchable talent for dullness, his central aim is not to expose the truth clearly, but to exhibit his profundity, his esotericity - in brief to stagger sophomores and other professors.

- Ch. 15 "The Dismal Science"

Notes on Democracy (1926)[edit]

- No man, I suppose, ever admits to himself candidly that he gets his living in a dishonourable way.

- Democratic man, dreaming eternally of Utopias, is ever a prey to shibboleths.

- Democratic man can understand the aims and aspirations of capitalism; they are, greatly magnified, simply his own aims and aspirations.

- An aristocratic society may hold that a soldier or a man of learning is superior to a rich manufacturer or banker, but in a democratic society the latter are inevitably put higher, if only because their achievement is more readily comprehended by the inferior man, and he can more easily imagine himself, by some favour of God, duplicating it.

- My business is not prognosis, but diagnosis. I am not engaged in therapeutics, but in pathology.

- Democracy is shot through with this delight in the incredible, this banal mysticism. I have alluded to its touching acceptance of the faith that progress is illimitable and ordained of God - that every human problem, in the very nature of things, may be solved.

- Democracy, in fact, is always inventing class distinctions, despite its theoretical abhorrence of them.

- What is not true, as everyone knows, is always immensely more fascinating and satisfying to the vast majority of men than what is true. Truth has a harshness that alarms them, and an air of finality that collides with their incurable romanticism.

- The demagogue is one who preaches doctrines he knows to be untrue to men he knows to be idiots. The demaslave is one who listens to what these idiots have to say and pretends to believe it himself.

- Ostensibly he is an altruist devoted whole-heartedly to the service of his fellow-men, and so abjectly public-spirited that his private interest is nothing to him. Actually, he is a sturdy rogue whose principal, and often sole aim in life is to butter his parsnips. His technical equipment consists simply of an armamentarium of deceits. It is his business to get and hold his job at all costs. If he can hold it by lying he will hold it by lying. if lying peters out he will try and hold it by embracing new truths. His ear is ever close to the ground.

- On elected politicians

- It is moral by his code to get into office by false pretences. It is moral to change convictions overnight. Anything is moral that furthers the main concern of his soul, which is to keep a place at the public trough.

- On elected politicians

- For what democracy needs most of all is a party that will separate the good that is in it theoretically from the evils that beset it practically, and then try to erect that good into a workable system. What it needs beyond everything is a party of liberty. It produces, true enough, occasional libertarians, just as despotism produces occasional regicides, but it treats them in the same drum-head way. It will never have a party of them until it invents and installs a genuine aristocracy, to breed them and secure them.*

- Thus the ideal of democracy is reached at last: it has become a psychic impossibility for a gentleman to hold office under the Federal Union, save by a combination of miracles that must tax the resourcefulness even of God. The fact has been rammed home by a constitutional amendment: every office-holder, when he takes oath to support the Constitution, must swear on his honour that, summoned to the death-bed of his grandmother, he will not take the old lady a bottle of wine. He may say so and do it, which makes him a liar, or he may say so and not do it, which makes him a pig. But despite that grim dilemma there are still idealists, chiefly professional Liberals, who argue that it is the duty of a gentleman to go into politics—that there is a way out of the quagmire in that direction. The remedy, it seems to me, is quite as absurd as all the other sure cures that Liberals advocate. When they argue for it, they simply argue, in words but little changed, that the remedy for prostitution is to fill the bawdyhouses with virgins. My impression is that this last device would accomplish very little: either the virgins would leap out of the windows, or they would cease to be virgins.

- Liberty means self-reliance, it means resolution, it means enterprise, it means the capacity for doing without. The free man is one who has won a small and precarious territory from the great mob of his inferiors, and is prepared and ready to defend it and make it support him. All around him are enemies, and where he stands there is no friend. He can hope for little help from other men of his own kind, for they have battles of their own to fight. He has made of himself a sort of god in his little world, and he must face the responsibilities of a god, and the dreadful loneliness.

- What the common man longs for in this world, before and above all his other longings, is the simplest and most ignominious sort of peace: the peace of a trusty in a well-managed penitentiary. He is willing to sacrifice everything else to it. He puts it above his dignity and he puts it above his pride. Above all, he puts it above his liberty. The fact, perhaps, explains his veneration for policemen, in all the forms they take–his belief that there is a mysterious sanctity in law, however absurd it may be in fact.

A policeman is a charlatan who offers, in return for obedience, to protect him (a) from his superiors, (b) from his equals, and (c) from himself. This last service, under democracy, is commonly the most esteemed of them all. In the United States, at least theoretically, it is the only thing that keeps ice-wagon drivers, Y.M.C.A. secretaries, insurance collectors and other such human camels from smoking opium, ruining themselves in the night clubs, and going to Palm Beach with Follies girls . . . Under the pressure of fanaticism, and with the mob complacently applauding the show, democratic law tends more and more to be grounded upon the maxim that every citizen is, by nature, a traitor, a libertine, and a scoundrel. In order to dissuade him from his evil-doing the police power is extended until it surpasses anything ever heard of in the oriental monarchies of antiquity.

- I have spoken hitherto of the possibility that democracy may be a self-limiting disease, like measles. It is, perhaps, something more: it is self-devouring. One cannot observe it objectively without being impressed by its curious distrust of itself—its apparently ineradicable tendency to abandon its whole philosophy at the first sign of strain. I need not point to what happens invariably in democratic states when the national safety is menaced. All the great tribunes of democracy, on such occasions, convert themselves, by a process as simple as taking a deep breath, into despots of an almost fabulous ferocity.

- Democracy always seems bent upon killing the thing it theoretically loves. I have rehearsed some of its operations against liberty, the very cornerstone of its political metaphysic. It not only wars upon the thing itself; it even wars upon mere academic advocacy of it. I offer the spectacle of Americans jailed for reading the Bill of Rights as perhaps the most gaudily humorous ever witnessed in the modern world. Try to imagine monarchy jailing subjects for maintaining the divine right of Kings! Or Christianity damning a believer for arguing that Jesus Christ was the Son of God! This last, perhaps, has been done: anything is possible in that direction. But under democracy the remotest and most fantastic possibility is a common place of every day. All the axioms resolve themselves into thundering paradoxes, many amounting to downright contradictions in terms. The mob is competent to rule the rest of us—but it must be rigorously policed itself. There is a government, not of men, but of laws—but men are set upon benches to decide finally what the law is and may be. The highest function of the citizen is to serve the state—but the first assumption that meets him, when he essays to discharge it, is an assumption of his disingenuousness and dishonour. Is that assumption commonly sound? Then the farce only grows the more glorious.

I confess, for my part, that it greatly delights me. I enjoy democracy immensely. It is incomparably idiotic, and hence incomparably amusing. Does it exalt dunderheads, cowards, trimmers, frauds, cads? Then the pain of seeing them go up is balanced and obliterated by the joy of seeing them come down. Is it inordinately wasteful, extravagant, dishonest? Then so is every other form of government: all alike are enemies to laborious and virtuous men. Is rascality at the very heart of it? Well, we have borne that rascality since 1776, and continue to survive. In the long run, it may turn out that rascality is necessary to human government, and even to civilization itself—that civilization, at bottom, is nothing but a colossal swindle. I do not know: I report only that when the suckers are running well the spectacle is infinitely exhilarating. But I am, it may be, a somewhat malicious man: my sympathies, when it comes to suckers, tend to be coy. What I can't make out is how any man can believe in democracy who feels for and with them, and is pained when they are debauched and made a show of. How can any man be a democrat who is sincerely a democrat?

1930s[edit]

- Laws are no longer made by a rational process of public discussion; they are made by a process of blackmail and intimidation, and they are executed in the same manner. The typical lawmaker of today is a man wholly devoid of principle — a mere counter in a grotesque and knavish game. If the right pressure could be applied to him, he would be cheerfully in favor of polygamy, astrology or cannibalism.

It is the aim of the Bill of Rights, if it has any remaining aim at all, to curb such prehensile gentry. Its function is to set a limitation upon their power to harry and oppress us to their own private profit. The Fathers, in framing it, did not have powerful minorities in mind; what they sought to hobble was simply the majority. But that is a detail. The important thing is that the Bill of Rights sets forth, in the plainest of plain language, the limits beyond which even legislatures may not go. The Supreme Court, in Marbury v. Madison, decided that it was bound to execute that intent, and for a hundred years that doctrine remained the corner-stone of American constitutional law.- The American Mercury (May 1930)

- All the benefit that a New Yorker gets out of Kansas is no more than what he might get out of Saskatchewan, the Argentine pampas, or Siberia. But New York to a Kansan is not only a place where he may get drunk, look at dirty shows and buy bogus antiques; it is also a place where he may enforce his dunghill ideas upon his betters.

- "The Calamity of Appomattox," The American Mercury (September 1930)

- Men become civilized, not in proportion to their willingness to believe, but in proportion to their readiness to doubt. The more stupid the man, the larger his stock of adamantine assurances, the heavier his load of faith.

- "What I Believe" in The Forum 84 (September 1930), p. 136

- I believe that religion, generally speaking, has been a curse to mankind — that its modest and greatly overestimated services on the ethical side have been more than overcome by the damage it has done to clear and honest thinking.

I believe that no discovery of fact, however trivial, can be wholly useless to the race, and that no trumpeting of falsehood, however virtuous in intent, can be anything but vicious.

I believe that all government is evil, in that all government must necessarily make war upon liberty; and the democratic form is as bad as any of the other forms.

I believe that the evidence for immortality is no better than the evidence of witches, and deserves no more respect.

I believe in the complete freedom of thought and speech — alike for the humblest man and the mightiest, and in the utmost freedom of conduct that is consistent with living in organized society.

I believe in the capacity of man to conquer his world, and to find out what it is made of, and how it is run.

I believe in the reality of progress.

I —But the whole thing, after all, may be put very simply. I believe that it is better to tell the truth than to lie. I believe that it is better to be free than to be a slave. And I believe that it is better to know than be ignorant.- "What I Believe" in The Forum 84 (September 1930), p. 139; some of these expressions were also used separately in other Mencken essays.

- To a clergyman lying under a vow of chastity any act of sex is immoral, but his abhorrence of it naturally increases in proportion as it looks safe and is correspondingly tempting. As a prudent man, he is not much disturbed by incitations which carry their obvious and certain penalties; what shakes him is the enticement bare of any probable secular retribution. Ergo, the worst and damndest indulgence is that which goes unwhipped. So he teaches that it is no sin for a woman to bear a child to a drunken and worthless husband, even though she may believe with sound reason that it will be diseased and miserable all its life, but if she resorts to any mechanical or chemical device, however harmless, to prevent its birth, she is doomed by his penology to roast in Hell forever, along with the assassin of orphans and the scoundrel who forgets his Easter duty.

- Treatise on the Gods (1930), p. 115

- The Jews could be put down very plausibly as the most unpleasant race ever heard of. As commonly encountered they lack any of the qualities that mark the civilized man: courage, dignity, incorruptibility, ease, confidence. They have vanity without pride, voluptuousness without taste, and learning without wisdom. Their fortitude, such as it is, is wasted upon puerile objects, and their charity is mainly a form of display.

- Treatise on the Gods (1930), pp. 345-346

- One hears murmurs against Mussolini on the ground that he is a desperado: the real objection to him is that he is a politician. Indeed, he is probably the most perfect specimen of the genus politician on view in the world today. His career has been impeccably classical. Beginning life as a ranting Socialist of the worst type, he abjured Socialism the moment he saw better opportunities for himself on the other side, and ever since then he has devoted himself gaudily to clapping Socialists in jail, filling them with castor oil, sending blacklegs to burn down their houses, and otherwise roughing them. Modern politics has produced no more adept practitioner.

- "Mussolini" in the Baltimore Evening Sun (3 August 1931), also in A Second Mencken Chrestomathy : New Selections from the Writings of America's Legendary Editor, Critic, and Wit (1994) edited by Terry Teachout, p. 34

- What are the hallmarks of a competent writer of fiction? The first, it seems to me, is that he should be immensely interested in human beings, and have an eye sharp enough to see into them, and a hand clever enough to draw them as they are. The second is that he should be able to set them in imaginary situations which display the contents of their psyches effectively, and so carry his reader swiftly and pleasantly from point to point of what is called a good story.

- The American Mercury (May 1933), p. 136

- If he became convinced tomorrow that coming out for cannibalism would get him the votes he needs so sorely, he would begin fattening a missionary in the White House yard come Wednesday.

- The American Mercury (March 1936) - referring to Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Fascism is not likely to be identical with the kinds on tap in Germany, Italy and Russia; indeed, it is very apt to come in under the name of anti-Fascism.

- The Baltimore Sun “Of The People, By The People,” (Nov. 6, 1938), p. 8.

- No man can get anywhere in this world in any really and endurable manner without some recourse to books.

- The Evening Sun (1939) in an editorial calling for adequate financial support for the Pratt Library; affixed to the wall inside the entrance to the Enoch Pratt Free Library Branch 2[2]

1940s–present[edit]

- When A annoys or injures B on the pretense of saving or improving X, A is a scoundrel.

- Newspaper Days: 1899-1906 (1941)

- Having lived all my life in a country swarming with messiahs, I have been mistaken, perhaps quite naturally, for one myself, especially by the others. It would be hard to imagine anything more preposterous. I am, in fact, the complete anti-Messiah, and detest converts almost as much as I detest missionaries. My writings, such as they are, have had only one purpose: to attain for H. L. Mencken that feeling of tension relieved and function achieved which a cow enjoys on giving milk. Further than that, I have had no interest in the matter whatsoever. It has never given me any satisfaction to encounter one who said my notions had pleased him. My preference has always been for people with notions of their own. I have believed all my life in free thought and free speech—up to and including the utmost limits of the endurable.

- "For the Defense Written for the Associated Press, for use in my obituary" (20 November 1940)

- In the present case it is a little inaccurate to say I hate everything. I am strongly in favor of common sense, common honesty and common decency. This makes me forever ineligible to any public office of trust or profit in the Republic. But I do not repine, for I am a subject of it only by force of arms.

- As quoted in LIFE magazine, Vol. 21, No. 6, (5 August 1946), p. 52; this has also been paraphrased as "It is inaccurate to say I hate everything. I am strongly in favor of common sense, common honesty, and common decency. This makes me forever ineligible for public office."

- A professional politician is a professionally dishonorable man. In order to get anywhere near high office he has to make so many compromises and submit to so many humiliations that he becomes indistinguishable from a streetwalker.

- As quoted in LIFE magazine, Vol. 21, No. 6, (5 August 1946), p. 48

- I believe in only one thing and that thing is human liberty. If ever a man is to achieve anything like dignity, it can happen only if superior men are given absolute freedom to think what they want to think and say what they want to say. I am against any man and any organization which seeks to limit or deny that freedom. . . [and] the superior man can be sure of freedom only if it is given to all men.

- As quoted in Letters of H. L. Mencken (1961) edited by Guy J. Forgue, p. xiii

- The state — or, to make the matter more concrete, the government — consists of a gang of men exactly like you and me. They have, taking one with another, no special talent for the business of government; they have only a talent for getting and holding office. Their principal device to that end is to search out groups who pant and pine for something they can't get and to promise to give it to them. Nine times out of ten that promise is worth nothing. The tenth time is made good by looting A to satisfy B. In other words, government is a broker in pillage, and every election is sort of an advance auction sale of stolen goods.

- As quoted in Charting the Candidates '72 (1972) by Ronald Van Doren, p. 7

- I well recall my emotions when I came upon the grave of Beethoven in the Central Friedhof, with its incomparable guard of honor — Mozart, Schubert, Gluck, Brahms, Hugo Wolf and Johann Strauss!

- H.L. Mencken : Thirty-five Years of Newspaper Work (1994) , p. 190; this work was written in 1941-1942 but sealed until 1991.

A Mencken Chrestomathy (1949)[edit]

- Nature abhors a moron.

- The most costly of all follies is to believe passionately in the palpably not true. It is the chief occupation of mankind.

- Conscience is the inner voice that warns us somebody may be looking.

- Immorality is the morality of those who are having a better time. You will never convince the average farmer's mare that the late Maud S. was not dreadfully immoral.

- An idealist is one who, on noticing that roses smell better than a cabbage, concludes that it will also make better soup.

- A celebrity is one who is known to many persons he is glad he doesn't know.

- Platitude — An idea (a) that is admitted to be true by everyone, and (b) that is not true.

- Remorse — Regret that one waited so long to do it.

- Self-respect — The secure feeling that no one, as yet, is suspicious.

- Truth — Something somehow discreditable to someone.

- We are here and it is now: further than that, all human knowledge is moonshine.

- Before a man speaks it is always safe to assume that he is a fool. After he speaks, it is seldom necessary to assume it.

- Historian — An unsuccessful novelist.

- Christian — One who is willing to serve three Gods, but draws the line at one wife.

- The New Deal began, like the Salvation Army, by promising to save humanity. It ended, again like the Salvation Army, by running flop-houses and disturbing the peace.

- Democracy is the art and science of running the circus from the monkey cage.

- The theory seems to be that so long as a man is a failure he is one of God's chillun, but that as soon as he has any luck he owes it to the Devil.

- Judge — A law student who marks his own examination-papers.

- Jury — A group of twelve men who, having lied to the judge about their hearing, health and business engagements, have failed to fool him.

- Lawyer — One who protects us against robbers by taking away the temptation.

- Jealousy is the theory that some other fellow has just as little taste.

- Wealth — Any income that is at least $100 more a year than the income of one's wife's sister's husband.

- Misogynist — A man who hates women as much as women hate one another.

- A man may be a fool and not know it — but not if he is married.

- Every decent man is ashamed of the government he lives under.

- In this world of sin and sorrow there is always something to be thankful for. As for me, I rejoice that I am not a Republican.

- Theology — An effort to explain the unknowable by putting it into terms of the not worth knowing.

- Creator — A comedian whose audience is afraid to laugh.

- Sunday — A day given over by Americans to wishing that they themselves were dead and in Heaven, and that their neighbors were dead and in Hell.

- A newspaper is a device for making the ignorant more ignorant and the crazy crazier.

- Conscience is a mother-in-law whose visit never ends.

- Q: If you find so much that is unworthy of reverence in the United States, then why do you live here?

A: Why do men go to zoos?

- A man who has throttled a bad impulse has at least some consolation in his agonies, but a man who has throttled a good one is in a bad way indeed.

- When women kiss, it always reminds one of prize-fighters shaking hands.[3]

- In every unbeliever's heart there is an uneasy feeling that, after all, he may awake after death and find himself immortal. This is his punishment for his unbelief. This is the agnostic's Hell.

- Puritanism: The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.

- Sententiæ: The Citizen and the State, p. 624

- The lunatic fringe wags the underdog.

- Sententiæ: The Citizen and the State

- If x is the population of the United States and y is the degree of imbecility of the average American, then democracy is the theory that x × y is less than y.

- Sententiæ: The Citizen and the State

- Love is the delusion that one woman differs from another.

- Sententiæ

- No matter how happily a woman may be married, it always pleases her to discover that there is a nice man who wishes that she were not.

Minority Report : H.L. Mencken's Notebooks (1956)[edit]

- We must respect the other fellow's religion, but only in the sense and to the extent that we respect his theory that his wife is beautiful and his children smart.

- 1

- I have often argued that a poet more than thirty years old is simply an overgrown child. I begin to suspect that there may be some truth in it.

- 13

- My guess is that well over eighty per cent of the human race goes through life without ever having a single original thought. That is to say, they never think anything that has not been thought before, and by thousands.

A society made up of individuals who were all capable of original thought would probably be unendurable. The pressure of ideas would simply drive it frantic. The normal human society is very little troubled by them. Whenever a new one appears the average man displays signs of dismay and resentment. The only way he can take in such a new idea is by translating it crudely into terms of more familiar ideas. That translation is one of the chief functions of politicians, not to mention journalists. They devote themselves largely to debasing the ideas launched by their betters. This debasement is intellectually reprehensible, but probably necessary to carry on the business of the world.- 13

- Human life is basically a comedy. Even its tragedies often seem comic to the spectator, and not infrequently they actually have comic touches to the victim. Happiness probably consists largely in the capacity to detect and relish them. A man who can laugh, if only at himself, is never really miserable.

- 15

- No government is ever really in favor of so-called civil rights. It always tries to whittle them down. They are preserved under all governments, insofar as they survive at all, by special classes of fanatics, often highly dubious.

- 33

- God is the immemorial refuge of the incompetent, the helpless, the miserable. They find not only sanctuary in His arms, but also a kind of superiority, soothing to their macerated egos: He will set them above their betters.

- 35

- Equality before the law is probably forever inattainable. It is a noble ideal, but it can never be realized, for what men value in this world is not rights but privileges.

- 36

- Government is actually the worst failure of civilized man. There has never been a really good one, and even those that are most tolerable are arbitrary, cruel, grasping and unintelligent. Indeed, it would not be far wrong to describe the best as the common enemy of all decent citizens. But there will be small hope of gaining adherents to this idea so long as government is thought of as an independent and somehow super-human organism, with powers, rights, and privileges transcending those of any other human aggregation.

- 68

- There are people who read too much: the bibliobibuli. I know some who are constantly drunk on books, as other men are drunk on whiskey or religion. They wander through this most diverting and stimulating of worlds in a haze, seeing nothing and hearing nothing.

- 71

- It is impossible to imagine the universe run by a wise, just and omnipotent God, but it is quite easy to imagine it run by a board of gods. If such a board actually exists it operates precisely like the board of a corporation that is losing money.

- 79

- The fact that what are commonly spoken of as rights are often really privileges is demonstrated in the case of the Jews. They resent bitterly their exclusion from certain hotels, resorts and other places of gathering, and make determined efforts to horn in. But the moment any considerable number of them horns in, the attractions of the place diminish, and the more pushful Jews turn to one where they are still nicht gewuenscht.

- 110

- Government, like any other organism, refuses to acquiesce in its own extinction. This refusal, of course, involves the resistance to any effort to diminish its powers and prerogatives. There has been no organized effort to keep government down since Jefferson's day. Ever since then the American people have been bolstering up its powers and giving it more and more jurisdiction over their affairs. They pay for that folly in increased taxes and diminished liberties. No government as such is ever in favor of the freedom of the individual. It invariably seeks to limit that freedom, if not by overt denial, then by seeking constantly to widen its own functions.

- 197

- Mankind has failed miserably in its effort to devise a rational system of government. [...] The art of government is the exclusive possession of quacks and frauds. It has been so since the earliest days, and it will probably remain so until the end of time.

- 201