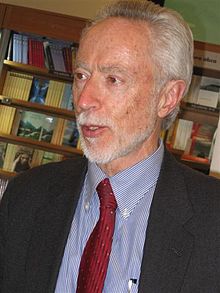

J. M. Coetzee

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

John Maxwell Coetzee (born 9 February 1940), often called J. M. Coetzee, is a South African-born writer and academic. A novelist and literary critic as well as a translator, Coetzee won the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature. He now lives in Australia.

Quotes[edit]

- Erasmus dramatizes a well-established political position: that of the fool who claims license to criticize all and sundry without reprisal, since his madness defines him as not fully a person and therefore not a political being with political desires and ambitions. The Praise of Folly, therefore sketches the possibility of a position for the critic of the scene of political rivalry, a position not simply impartial between the rivals but also, by self-definition, off the stage of rivalry altogether.

- “Erasmus’s Praise of Folly: Rivalry and Madness,” Neophilologus 76 (1992), p. 1

- It is not, then, in the content or substance of folly that its difference from truth lies, but in where it comes from. It comes not from ‘the wise man’s mouth’ but from the mouth of the subject assumed not to know and speak the truth.

- “Erasmus: Madness and Rivalry,” Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship (1996), p. 94

- In its conception the literature prize belongs to days when a writer could still be thought of as, by virtue of his or her occupation, a sage, someone with no institutional affiliations who could offer an authoritative word on our times as well as on our moral life. (It has always struck me as strange, by the way, that Alfred Nobel did not institute a philosophy prize, or for that matter that he instituted a physics prize but not a mathematics prize, to say nothing of a music prize - music is, after all, more universal than literature, which is bound to a particular language.) The idea of writer as sage is pretty much dead today. I would certainly feel very uncomfortable in the role.

- Dagens Nyheter interview with David Attwell (December 8, 2003)

- [Being peppered with invitations to travel far and wide to give lectures] has always seemed to me one of the stranger aspects of literary fame: you prove your competence as a writer and an inventor of stories, and then people clamour for you to make speeches and tell them what you think about the world.

- Dagens Nyheter interview with David Attwell (December 8, 2003)

- As for September 11, let us not too easily grant the Americans possession of that date on the calendar. Like May 1 or July 14 or December 25, September 11 may seem full of significance to some people, while to other people it is just another day.

- Dagens Nyheter interview with David Attwell (December 8, 2003)

- To any thinking person, it must be obvious that there is something badly wrong in relations between human beings and the animals that human beings rely on for food; and that in the past 100 or 150 years whatever is wrong has become wrong on a huge scale, as traditional animal husbandry has been turned into an industry using industrial methods of production. … It would be a mistake to idealise traditional animal husbandry as the standard by which the animal-products industry falls short: traditional animal husbandry is brutal enough, just on a smaller scale. A better standard by which to judge both practices would be the simple standard of humanity: is this truly the best that human beings are capable of?

- “Animals can't speak for themselves - it's up to us to do it!,” in theage.com.au (February 22, 2007)

- A dictum [Beckett] quotes from his favourite philosopher, the second-generation Cartesian Arnold Geulincx (1624-1669) suggests his overall stance toward the political: ubi nihil vales, ibi nihil velis, which may be glossed: Don’t invest hope or longing in an arena where you have no power.

- “The Making of Samuel Beckett,” New York Review of Books, vol. LVI, no. 7 (April 30, 2009), p. 13

- Light in tone, the novel [Murphy] is Beckett’s response to the therapeutic orthodoxy that the patient should learn to engage with the larger world on the world’s terms.

- “The Making of Samuel Beckett,” New York Review of Books, vol. LVI, no. 7 (April 30, 2009), p. 14

- The activity of writing, then, is not to be distinguished from the activity of self-exploration. It consists in contemplating the sea of internal images, discerning connections, and setting these out in grammatical sentences (“I could never conceive of a network of meaning too complex to be expressed in a series of grammatical sentences,” says Murnane, whose views on grammar are firm, even pedantic.)

- “The quest for the girl from Bendigo Street,” The New York Review of Books, v. 59. n. 20, December 20, 2012

Life & Times of Michael K (1983)[edit]

- I could live here forever, he thought, or till I die. Nothing would happen, every day would be the same as the day before, there would be nothing to say. The anxiety that belonged to the time on the road began to leave him. Sometimes, as he walked, he did not know whether he was awake or asleep. He could understand that people should have retreated here and fenced themselves in with miles and miles of silence; he could understand that they should have wanted to bequeath the privilege of so much silence to their children and grandchildren in perpetuity (though by what right he was not sure); he wondered whether there were not forgotten corners and angles and corridors between the fences, land that belonged to no one yet. Perhaps if one flew high enough, he thought, one would be able to see.

- There seemed nothing to do but live.

- He closed his eyes and tried to recover in his imagination the mudbrick walls and reed roof of her stories, the garden of prickly pear, the chickens scampering for the feed scattered by the little barefoot girl. And behind that child, in the doorway, her face obscured by shadow, he searched for a second woman, the woman from whom his mother had come into the world. When my mother was dying in the hospital, he thought, when she knew her end was coming, it was not me she looked to but someone who stood behind me: her mother or the ghost of her mother. To me she was a woman but to herself she was still a child calling to her mother to hold her hand and help her. And her own mother, in the secret life we do not see, was a child too. I come from a line of children without end.

- Do any of us believe in what we are doing here? I doubt it. Her NCO husband least of all. We are given an old racetrack and a quantity of barbed wire and told to effect a change in men's souls. Not being experts on the soul but assuming cautiously that it has some connection with the body, we set our captives to doing pushups and marching back and forth.

- He is like a stone, a pebble that, having lain around quietly minding its own business since the dawn of time, is now suddenly picked up and tossed randomly from hand to hand. A hard little stone, barely aware of its surroundings, enveloped in itself and its interior life. He passes through these institutions and camps and hospitals and God knows what else like a stone. Through the intestines of war. An unbearing, unborn creature.

- Though this is a large country, so large that you would think there would be space for everyone, what I have learned from life tells me that it is hard to keep out of the camps. Yet I am convinced there are areas that lie between the camps and belong to no camp, not even to the catchment areas of the camps — certain mountaintops, for example, certain islands in the middle of swamps, certain arid strips where human beings may not find it worth their while to live. I am looking for such a place in order to settle there, perhaps only till things improve, perhaps forever. I am not so foolish, however, as to imagine that I can rely on maps and roads to guide me. Therefore I have chosen you to show me the way.

Boyhood (1998)[edit]

- Coming to the farm from Worcester, where Coloured people seem to have to beg for whatever they get, he is relieved at how correct and formal relations are between his uncle and the volk. Each morning, his uncle confers with his two men about the day's tasks. He does not give them orders. Instead he proposes the tasks that need to be done, as if dealing cards on a table; his men deal their own cards too. In between, there are pauses, long, reflective silences in which nothing happens.

- The secret and sacred word that binds him to the farm is 'belong'. Out in the veld by himself he can breathe the word aloud: I belong on the farm. What he really believes but does not utter, what he keeps to himself for fear that the spell will end, is a different form of the word: I belong to the farm. He tells no one because the word is misunderstood so easily, turned so easily to its inverse: The farm belongs to me. The farm will never belong to him, he will never be more than a visitor: he accepts that.

- Sometimes when he is among the sheep — when they have been rounded up to be dipped, and are penned tight and cannot get away — he wants to whisper to them, warn them of what lies in store. But then in their yellow eyes he catches a glimpse of something that silences him: a resignation, a foreknowledge not only of what happens to sheep at the hands of Ros behind the shed, but of what awaits them at the end of their long, thirsty ride to Cape Town on the transport lorry. They know it all, down to the finest detail, and yet they submit. They have calculated the price and are prepared to pay it — the price of being on earth, the price of being alive.

- The boy is special, Aunt Annie told his mother, and his mother in turn told him. But what kind of special? No one ever says.

Disgrace (1999)[edit]

- Although he devoted hours of each day to his new discipline, he finds its first premise, as enunciated in the Communications 101 handbook, preposterous: 'Human society has created language in order that we may communicate our thoughts, feelings, and intentions to each other.' His own opinion, which he does not air, is that the origins of speech lie in song, and the origins of song in the need to fill out with sound the overlarge and rather empty human soul.

- p. 3-4

- Isaacs has a cheap Bic pen in his hand. He runs his fingers down the shaft, inverts it, runs his fingers down the shaft, over and over, in a motion that is mechanical rather than impatient.

- Talking to Petrus is like punching a bag of sand.

'Are you giving him up?'

'Yes, I am giving him up.'

The Lives of Animals (1999)[edit]

- Princeton University Press, Human Values series, 1999. On Google Books.

- The people who lived in the countryside around Treblinka—Poles, for the most part—said that they did not know what was going on in the camp; said that, while in a general way they might have guessed what was going on, they did not know for sure; said that, while in a sense they might have known, in another sense they did not know, could not afford to know, for their own sake.

- p. 19

- I return one last time to the places of death all around us, the places of slaughter to which, in a huge communal effort, we close our hearts. Each day a fresh holocaust, yet, as far as I can see, our moral being is untouched.

- p. 35

- What he dreads is that, during a lull in the conversation, someone will come up with what he calls The Question—“What led you, Mrs. Costello, to become a vegetarian?”—and that she will then get on her high horse and produce what he and Norma call The Plutarch Response. … The response in question comes from Plutarch's moral essays. His mother has it by heart; he can reproduce it only imperfectly. “You ask me why I refuse to eat flesh. I, for my part, am astonished that you can put in your mouth the corpse of a dead animal, am astonished that you do not find it nasty to chew hacked flesh and swallow the juices of death-wounds.” Plutarch is a real conversation-stopper: it is the word juices that does it. Producing Plutarch is like throwing down a gauntlet; after that, there is no knowing what will happen.

- p. 38

- “But your own vegetarianism, Mrs. Costello,” says President Garrard, pouring oil on troubled waters: “it comes out of moral conviction, does it not?”

“No, I don't think so,” says his mother. “It comes out of a desire to save my soul.”

Now there truly is a silence, broken only by the clink of plates as the waitresses set baked Alaskas before them.

“Well, I have a great respect for it,” says Garrard. “As a way of life.”

“I'm wearing leather shoes,” says his mother. “I'm carrying a leather purse. I wouldn't have overmuch respect if I were you.”

“Consistency,” murmurs Garrard. “Consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds. Surely one can draw a distinction between eating meat and wearing leather.”

“Degrees of obscenity,” she replies.- pp. 43-44

- It was from the Chicago stockyards that the Nazis learned how to process bodies.

- p. 53

- “It's been such a short visit, I haven't had time to make sense of why you have become so intense about the animal business.”

She watches the wipers wagging back and forth. “A better explanation,” she says, “is that I have not told you why, or dare not tell you. When I think of the words, they seem so outrageous that they are best spoken into a pillow or into a hole in the ground, like King Midas.”

“What is it you can't say?”

“It's that I no longer know where I am. I seem to move around perfectly easily among people, to have perfectly normal relations with them. Is it possible, I ask myself, that all of them are participants in a crime of stupefying proportions? Am I fantasizing it all? I must be mad! Yet every day I see the evidences. The very people I suspect produce the evidence, exhibit it, offer it to me. Corpses. Fragments of corpses that they have bought for money. It is as if I were to visit friends, and to make some polite remark about the lamp in their living room, and they were to say, ‘Yes, it's nice, isn't it? Polish-Jewish skin it's made of, we find that's best, the skins of young Polish-Jewish virgins.’ And then I go to the bathroom and the soap-wrapper says, ‘Treblinka— 100% human stearate.’ Am I dreaming, I say to myself?”- p. 69

Youth (2002)[edit]

- At the Everyman Cinema there is a season of Satyajit Ray. He watches the Apu trilogy on successive nights in a state of rapt absorption. In Apu's bitter, trapped mother, his engaging, feckless father he recognizes, with a pang of guilt, his own parents. But it is the music above all that grips him, dizzyingly complex interplays between drums and stringed instruments, long arias on the flute whose scale or mode — he does not know enough about music theory to be sure which — catches at his heart, sending him into a mood of sensual melancholy that last long after the film has ended.

- Hitherto he has found in Western music, in Bach above all, everything he needs. Now he encounters something that is not in Bach, though there are intimations of it: a joyous yielding of the reasoning, comprehending mind to the dance of the fingers. He hunts through record shops, and in one of them finds an LP of a sitar player named Ustad Vilayat Khan, with his brother — a younger brother, to judge from the picture — on a veena, and an unnamed tabla player. He does not have a gramophone of this own, but he is able to listen to the first ten minutes in the shop. It is all there: the hovering exploration of tone-sequences, the quivering emotion, the ecstatic rushes. He cannot believe his good fortune. A new continent and all for a mere nine shillings! He takes the record back to his room, packs it away between sleeves of cardboard till the day he will able to listen to it again.

Elizabeth Costello (2003)[edit]

- She no longer believes very strongly in belief... Belief may be no more, in the end, than a source of energy, like a battery which one clips into an idea to make it run. As happens when one writes: believing whatever has to be believed in order to get the job done.

Slow Man (2004)[edit]

- But truth is not spoken in anger. Truth is spoken, if it ever comes to be spoken, in love.

- Can desire grow out of admiration, or are the two quite distinct species? What would it be like to lie side by side, naked, breast to breast, with a woman one principally admires?

- Paul here is unhappy because unhappiness is second nature to him but more particularly because he has not the faintest idea of how to bring about his heart's desire. And I am unhappy because nothing is happening. Four people in four corners, moping, like tramps in Beckett, and myself in the middle, wasting time, being wasted by time.

- Why does love, even such love as he claims to practise, need the spectacle of beauty to bring it to life? What, in the abstract, do shapely legs have to do with love, or for that matter with desire? Or is that just the nature of nature, about which one does not ask questions?

- Our lies reveal as much about us as our truths.

Diary of a Bad Year (2007)[edit]

- Someone should put together a ballet under the title Guantanamo, Guantanamo! A corps of prisoners, their ankles shackled together, thick felt mittens on their hands, muffs over their ears, black hoods over their heads, do the dances of the persecuted and the desperate. Around them, guards in olive green uniforms prance with demonic energy and glee, cattle prods and billy-clubs at the ready. They touch the prisoners with the prods and the prisoners leap; they wrestle prisoners to the ground and shove the clubs up their anuses and the prisoners go into spasms. In a corner, a man on stilts in a Donald Rumsfeld mask alternately writes at his lectern and dances ecstatic little jigs.

One day it will be done, though not by me. It may even be a hit in London and Berlin and New York. It will have absolutely no effect on the people it targets, who could not care less what ballet audiences think of them.

- As during the time of kings it would have been naive to think that the king’s firstborn son would be the fittest to rule, so in our time it is naive to think that the democratically elected ruler will be the fittest. The rule of succession is not a formula for identifying the best ruler, it is a formula for conferring legitimacy on someone or other and thus forestalling civil conflict.

- p. 14

- If you have reservations about the system and want to change it, the democratic argument goes, do so within the system: put yourself forward as a candidate for political office, subject yourself to the scrutiny and the vote of fellow citizens. Democracy does not allow for politics outside the democratic system. In this sense, democracy is totalitarian.

- p. 15

- Machiavelli says that if as a ruler you accept that your every action must pass moral scrutiny, you will without fail be defeated by an opponent who submits to no such moral test. To hold on to power, you have not only to master the crafts of deception and treachery but to be prepared to use them where necessary.

- p. 17

- The modern state appeals to morality, to religion, and to natural law as the ideological foundation of its existence. At the same time it is prepared to infringe any or all of these in the interest of self-preservation.

- p. 17

- The typical reaction of liberal intellectuals is to seize on the contradiction here: How can something be both wrong and right, or at least both wrong and OK, at the same time? What liberal intellectuals fail to see is that this so-called contradiction expresses the quintessence of the Machiavellian and therefore the modern, a quintessence that has been thoroughly absorbed by the man in the street. The world is ruled by necessity, says the man in the street, not by some abstract moral code. We have to do what we have to do.

If you wish to counter the man in the street, it cannot be by appeal to moral principles, much less by demanding that people should run their lives in such a way that there are no contradictions between what they say and what they do. Ordinary life is full of contradictions; ordinary people are used to accommodating them. Rather, you must attack the metaphysical, supra-empirical status of necessità and show that to be fraudulent.- p. 17

Quotes about J M Coetzee[edit]

- I admire writers like J.M. Coetzee, Nuruddin Farah, Michael Ondaatje, I can name several.

- Abdulrazak Gurnah Interview (2021)

- (whom of those you have read recently have you found impressive?) AO: The South Africans: Nadine Gordimer, J. M. Coetzee, and André Brink.

- Amos Oz 1986 interview in We Are All Close: Conversations with Israeli Writers by Haim Chertok (1989)

External links[edit]

- Biography at nobelprize.org

- Nobel Lecture at nobelprize.org

- J. M. Coetzee at the Nobel Prize Internet Archive

- "The Lives of Animals", delivered for The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Princeton (1997)

- "A Word from J. M. Coetzee", address read by Hugo Weaving at the opening of the exhibition "Voiceless: I Feel Therefore I Am" by Voiceless: The Animal Protection Institute, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (22 February 2007)

- J. M. Coetzee at The New York Review of Books

- J. M. Coetzee at The New York Times

- An academic blog about writing a dissertation on Coetzee

- J. M. Coetzee: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center

- J. M. Coetzee's page as a member of the Australian Research Council project, 'Other Worlds: Forms of World Literature'

- Videos

Categories:

- Academics from South Africa

- Novelists from South Africa

- Essayists

- Linguists

- Booker Prize winners

- 1940 births

- Living people

- Vegetarians

- Literary critics

- Translators

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- People from Cape Town

- Postmodern authors

- Anti-apartheid activists

- Atheists

- Nobel laureates from South Africa

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- University of Chicago faculty