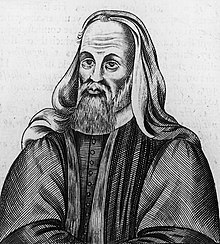

Pelagius

(Redirected from Pelagianism)

Pelagius (c. 390-418) was an Irish or British ascetic moralist, who became well known throughout the Roman Empire in Late Antiquity. He was declared a heretic by the Council of Carthage. His doctrine became known as Pelagianism.

Quotes[edit]

On The Christian Life[edit]

- as translated by B. R. Rees in Pelagius: Life and Letters (Boydell Press: 2004)

- Their faith alone will not profit them, because they have not done works of righteousness.

- Unless a man has despised worldly things, he shall not receive those which are divine.

- Let no man judge himself to be a Christian, unless he is one who both follows the teaching of Christ and imitates his example.

- Do you consider a man to be a Christian by whose bread no hungry man is ever filled?

- He is a Christian

- who shows compassion to all,

- who is not at all provoked by wrong done to him,

- who does not allow the poor to be oppressed in his presence,

- who helps the wretched,

- who succors the needy,

- who mourns with the mourners,

- who feels another's pain as if it were his own,

- who is moved to tears by the tears of others,

- whose house is common to all,

- whose door is closed to no one,

- whose table no poor man does not know,

- whose food is offered to all,

- whose goodness all know and at whose hands no one experiences injury,

- who serves God all day and night,

- who ponders and meditates upon his commandments unceasingly,

- who is made poor in the eyes of the world so that he may become rich before God.

- He is a Christian ...

- who is seen to have no feigning or pretense in his heart,

- whose soul is open and unspotted,

- whose conscience is faithful and pure,

- whose whole mind is on God,

- whose whole hope is in Christ,

- who desires heavenly things rather than earthly.

- Whenever I have to speak on the subject of moral instruction and conduct of a holy life, it is my practice first to demonstrate the power and quality of human nature and to show what it is capable of achieving, and then to go on to encourage the mind of my listener to consider the idea of different kinds of virtues, in case it may be of little or no profit to him to be summoned to pursue ends which he has perhaps assumed hitherto to be beyond his reach; for we can never end upon the path of virtue unless we have hope as our guide and compassion.

- p. 36

- It was because God wished to bestow on the rational creature the gift of doing good of his own free will and the capacity to exercise free choice, by implanting in man the possibility of choosing either alternative. ... He could not claim to possess the good of his own volition, unless he was the kind of creature that could also have possessed evil. Our most excellent creator wished us to be able to do either but actually to do only one, that is, good, which he also commanded, giving us the capacity to do evil only so that we might do His will by exercising our own. That being so, this very capacity to do evil is also good – good, I say, because it makes the good part better by making it voluntary and independent, not bound by necessity but free to decide for itself.

- p. 38

- Yet we do not defend the good of nature to such an extent that we claim that it cannot do evil, since we undoubtedly declare also that it is capable of good and evil; we merely try to protect it from an unjust charge, so that we may not seem to be forced to do evil through a fault of our nature, when, in fact, we do neither good nor evil without the exercise of our will and always have the freedom to do one of the two, being always able to do either.

- p. 43

- Nothing impossible has been commanded by the God of justice and majesty. ... Why do we indulge in pointless evasions, advancing the frailty of our own nature as an objection to the one who commands us? No one knows better the true measure of our strength than he who has given it to us nor does anyone understand better how much we are able to do than he who has given us this very capacity of ours to be able; nor has he who is just wished to command anything impossible or he who is good intended to condemn a man for doing what he could not avoid doing.

- p. 53

Letter to Demetrias[edit]

- as translated by B. Rees, in Readings in World Christian History (2013), pp. 206-210

- Whenever I have to speak on the subject of moral instruction and the conduct of a holy life, it is my practice first to demonstrate the power and quality of human nature.

- We can never enter upon the path to virtue unless we have hope as our guide and companion.

- The best incentive for the mind consists in teaching it that it is possible to do anything which one really wants to do.

- We must now take precautions to prevent you from being embarrassed by something in which the ignorant majority is at fault for lack of proper consideration, and so from supposing with them, that man has not been created truly good simply because he is able to do evil. ... If you reconsider this matter carefully and force your mind to apply a more acute understanding to it, it will be revealed to you that man's status is better and higher for the very reason for which it is thought to be inferior: it is on this choice between two ways, on this freedom to choose either alternative, that the glory of the rational mind is based, it is in this that the whole honor of our nature consists, it is from this that its dignity is derived.

- Love of wealth is insatiable, desire for honour knows no fulfilment; possessions destined to meet with a speedy end are sought endlessly. But divine wisdom, heavenly riches, immortal honours we neglect in our indifference and sloth, and, as for spiritual riches, either we do not touch them at all or, if we get a slight taste of them, we at once suppose that we have had enough. The divine Wisdom invites us to its feasts in quite different terms: Those who eat me, she says, will hunger for more, and those who drink me will thirst for more (Sir.24.21). No one can have enough of such feasts or ever suffers from squeamishness because he has had too much: the more he drinks from that source the greater will be each man's capacity and eagerness for more.

On Virginity[edit]

- If you depart from evil but fail to do good, you transgress the law, which is fulfilled not simply by abominating evil deeds but also by performing good works.

- Harrison, Carol (2016). "Truth in a Heresy?". The Expository Times 112 (3): 78–82. DOI:10.1177/001452460011200302.

On The Possiblity of Not Sinning[edit]

- as translated by B. R. Rees in Pelagius: Life and Letters (Boydell Press: 2004)

- When will a man guilty of any crime or sin accept with a tranquil mind that his wickedness is a product of his own will, not of necessity, and allow what he now strives to attribute to nature to be ascribed to his own free choice? It affords endless comfort to transgressors of the divine law if they are able to believe that their failure to do something is due to inability rather than disinclination, since they understand from their natural wisdom that no one can be judged for failing to do the impossible and that what is justifiable on grounds of impossibility is either a small sin or none at all.

- p. 167

- Under the plea that it is impossible not to sin, they are given a false sense of security in sinning ... Anyone who hears that it is not possible for him to be without sin will not even try to be what he judges to be impossible, and the man who does not try to be without sin must perforce sin all the time, and all the more boldly because he enjoys the false security of believing that it is impossible for him not to sin ... But if he were to hear that he is able not to sin, then he would have exerted himself to fulfil what he now knows to be possible when he is striving to fulfil it, to achieve his purpose for the most part, even if not entirely.

- p. 168