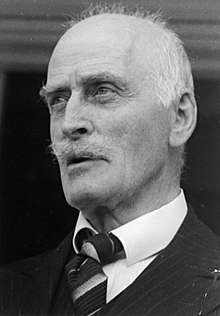

Knut Hamsun

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Knut Hamsun (August 4, 1859 – February 19, 1952) was a Norwegian author and Nobel laureate.

| This article on an author is a stub. You can help Wikiquote by expanding it. |

Quotes[edit]

- Nothing helped; I was fading helplessly away with open eyes, staring straight at the ceiling. Finally I stuck my forefinger in my mouth and took to sucking on it. Something began stirring in my brain, some thought in there scrambling to get out, a stark-staring mad idea: what if I gave a bite? And without a moment's hesitation I squeezed my eyes shut and clenched my teeth together. I jumped up. I was finally awake.

- Hunger (1890), p. 110 in Robert Bly's translation.

- And love became the world's origin and the world's ruler, yet littered its path is with flowers and blood, flowers and blood.

- Victoria (1898)

- In old age... we are like a batch of letters that someone has sent. We are no longer in the past, we have arrived.

- Wanderers (1909)

- I am not worthy to speak loudly of Adolf Hitler, nor do his life and deeds call for sentimental arousal. He was a warrior, a warrior for mankind, and a preacher of the gospel of justice for all nations. He was a reformer of the highest order, and his historical fate was that he lived in a time of unequalled cruelty, which felled him in the end. Thus the ordinary Western European may look upon Adolf Hitler. And we, his close followers, bow our heads at his death.

- An obituary for Adolf Hitler, Aftenposten (7 May 1945)

Novels[edit]

Hunger (1890)[edit]

- It was in those days when I wandered about hungry in Kristiania, that strange city which no one leaves before it has set its mark upon him. . . .

- Part One - p.3 (Book opening line) [Page numbers per the 2016 Canongate Books Ltd. paperback edition (which incorporates the 1996 Sverre Lyngstad translation into English).]

- I sit there on the bench and write 1848 dozens of times; I write this number criss-cross in all possible shapes and wait for a usable idea to occur to me. A swarm of loose thoughts is fluttering about in my head. The mood of the dying day makes me despondent and sentimental. Autumn has arrived and has already begun to put everything into a deep sleep; flies and other insects have suffered their first setback, and up in the trees and down on the ground you can hear the sounds of struggling life, pottering, ceaselessly rustling, labouring not to perish. All crawling things are stirring once more; they stick their yellow heads out of the moss, lift their legs and grope their way with their long feelers, before they suddenly give out, rolling over and turning up their bellies. Every growing thing has received its distinctive mark, a gentle breath of the first frost; the grass stems, stiff and pale, strain upwards towards the sun, and the fallen leaves rustle along the ground with a sound like that of wandering silkworms. It's autumn, the very carnival of transience; the roses have an inflamed flush, their blood-red colour tinged with a wonderfully hectic hue.

I felt I was myself a crawling insect doomed to perish, seized by destruction in the midst of a whole world ready to go to sleep.- Part One - p.29-30

- Suddenly one or two good sentences occur to me, suitable for a sketch or story, nice linguistic flukes the likes of which I had never experienced before. I lie there repeating these words to myself and find that they are excellent. Presently they're joined by others, I'm at once wide awake, sit up and grab paper and pencil from the table behind my bed. It was as though a vein had burst inside me - one word follows another, they connect with one another and turn into situations; scenes pile on top of other scenes, actions and dialogue well up in my brain, and a wonderful sense of pleasure takes hold of me. I write as if possessed, filling one page after another without a moment's pause. My thoughts strike me so suddenly and continue to pour out so abundantly that I lose a lot of minor details I'm not able to write down fast enough, though I am working at full blast. They continue to crowd in on me, I am full of my subject, and every word I write is put in my mouth.

It goes on and on, it takes such a wonderfully long time before this singular moment ceases to be; I have 15 to 20 written pages lying on my knees in front of me when I finally stop and put my pencil away. Now, if these pages were really worth something, then I was saved!- Part One - p.33

- I walked very slowly, passed Majorstuen, continued onward, always onward, walked for hours, and finally got out to the Bogstad Woods.

Here I stepped off the road and sat down to rest. Then I busied myself looking for a likely place, began to scrape together some heather and juniper twigs and made a bed on a small slope where it was fairly dry, opened my parcel and took out the blanket. I was tired and fagged out from the long walk and went to bed at once. I tossed and turned many times before I finally got settled; my ear hurt - it was a bit swollen from the blow of the fellow on the hay load and I couldn't lie on it. I took off my shoes and placed them under my head, with the big wrapping paper on top of them.

A brooding darkness was all around me. Everything was still, everything. But up aloft soughed the eternal song of wind and weather, that remote, tuneless hum which is never silent. I listened so long to this endless, faint soughing that it began to confuse me; it could only be the symphonies coming from the whirling worlds above me, the stars intoning a hymn. . . .- Part One - p.45

- Here I was walking around so hungry that my intestines were squirming inside me like snakes, and I had no guarantee there would be something in the way of food later in the day either. And as time went on I was getting more and more hollowed out, spiritually and physically, and I stooped to less and less honourable actions every day. I lied without blushing to get my way, cheated poor people out of their rent, even had to fight off the thought, mean as could be, of laying hands on other people's blankets, all without remorse, without a bad inner conscience. Rotten patches were beginning to appear in my inner being, black spongy growths that were spreading more and more. And God sat up in his heaven keeping a watchful eye on me, making sure that my destruction took place according to all the rules of the game, slowly and steadily, with no let-up. But in the pit of hell the devils were raising their hackles in fury because it was taking me such a long time to commit a cardinal sin, an unforgivable sin for which God in his righteousness had to cast me down. . . .

- Part One - p.49-50

- If only one had a piece of bread! One of those delicious little loaves of rye bread that you could munch on as you walked the streets. And I kept picturing to myself just the sort of rye bread it would have been good to have. I was bitterly hungry, wished myself dead and gone, grew sentimental and cried. There would never be an end to my misery!

[...] My hunger pains were excruciating and didn't leave me for a moment. [...] I hadn't had enough to eat for many, many weeks before this thing came up, and my strength had diminished considerably lately. [...] And hadn't I lived like a miser, eaten bread and milk when I had plenty, bread when I had little, and gone hungry when I had nothing?

[...] I reviled myself for my poverty, shouted epithets at myself, invented insulting names, priceless treasures of coarse abusive language that I heaped on myself. I kept this up until I was nearly home.- Part Two - p.66, 67, 68

- I passed my hand up along my cheeks: thin - of course I was thin, my cheeks were like two bowls with the bottoms in. Oh Lord! I shuffled on.

But I stopped again. I must be just incredibly thin. My eyes were sinking deep into my skull. What, exactly, did I look like? The devil only knew why you had to be turned into a veritable freak just because of hunger! I experienced rage once more, its final flare-up, a spasm. God help us, what a face, eh? Here I was, with a head on my shoulders without its equal in the whole country, and with a pair of fists, by golly, that could grind the town porter to fine dust, and yet I was turning into a freak from hunger, right here in the city of Kristiania! Was there any rhyme or reason in that? I had put my shoulders to the wheel and toiled day and night, like a nag lugging a parson; I had read till my eyes were bursting from their sockets and starved till my wits took leave of my brain - and where the hell had it gotten me? Even the streetwalkers prayed to God to free them from the sight of me. But now it was going to stop, understand; it was going to stop, or I'd be damned! . . .- Part Two - p.96-97

- Then, one afternoon, one of my articles was finished at last and, pleased and happy, I stuck it in my pocket and went up to the 'Commander'. It was high time I bestirred myself to get some money again. I didn't have very many øre left. [...]

He takes the papers out of my hand and starts leafing through them. He turns his face in my direction. [...]

"Everything we can use must be so popular," he answers. "You know the sort of public we have. Couldn't you try to make it a bit simpler? Or else come up with something that people understand better?"- Part Three - p.110, 111

- Good God, what an awful state I was in! I was so thoroughly sick and tired of my whole wretched life that I didn't find it worth my while to go on fighting in order to hang onto it. The hardships had got the better of me, they had been too gross; I was so strangely ruined, nothing but a shadow of what I once was. My shoulders had slumped completely to one side, and I had fallen into the habit of leaning over sharply when I walked, in order to spare my chest what little I could. I had examined my body a few days ago, at noon up in my room, and I had stood there and cried over it the whole time. I had been wearing the same shirt for weeks on end, it was stiff with old sweat and had gnawed my naval to bits.

- Part Three - p.142-143

Quotes about Knut Hamsun[edit]

- Closing the door, I opened a suitcase and took out a copy of Knut Hamsun's Hunger. It was a treasured piece, constantly with me since the day I stole it from the Boulder library. I had read it so many times that I could recite it.

- per Arturo Bandini, a fictional character created by John Fante. From the final page of John Fante's fourth Bandini novel, Dreams from Bunker Hill (1982).