The Man Who Laughs

(Redirected from L'Homme qui rit.)

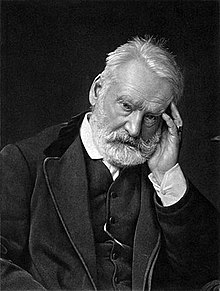

The Man Who Laughs (also published under the title By Order of the King) is a novel by Victor Hugo. It was published in April 1869 under the French title L'Homme qui rit.

Quotes[edit]

- They had done him the honor to take him for a madman, but had set him free on discovering that he was only a poet.

- Any one who has lived a solitary life knows how deeply seated monologue is in one's nature. Speech imprisoned frets to find a vent. To harangue space is an outlet. To speak out aloud when alone is as it were to have a dialogue with the divinity which is within.

- Fortunately Ursus had never gone into the Low Countries; there they would certainly have weighed him, to ascertain whether he was of the normal weight, above or below which a man is a sorcerer. In Holland this weight was sagely fixed by law. Nothing was simpler or more ingenious. It was a clear test. They put you in a scale, and the evidence was conclusive if you broke the equilibrium. Too heavy, you were hanged; too light, you were burned. To this day the scales in which sorcerers were weighed may be seen at Oudewater, but they are now used for weighing cheeses; how religion has degenerated!

- Ursus had communicated to Homo a portion of his talents: such as to stand upright, to restrain his rage into sulkiness, to growl instead of howling, etc.; and on his part, the wolf had taught the man what he knew—to do without a roof, without bread and fire, to prefer hunger in the woods to slavery in a palace.

- By friction gold loses every year a fourteen hundredth part of its bulk. This is what is called the Wear. Hence it follows that on fourteen hundred millions of gold in circulation throughout the world, one million is lost annually. This million dissolves into dust, flies away, floats about, is reduced to atoms, charges, drugs, weighs down consciences, amalgamates with the souls of the rich whom it renders proud, and with those of the poor whom it renders brutish.

- He did not smile, as we have already said, but he used to laugh; sometimes, indeed frequently, a bitter laugh. There is consent in a smile, while a laugh is often a refusal.

- Barbara, Duchess of Cleveland and Countess of Southampton, had a marmoset for a page. Frances Sutton, Baroness Dudley, eighth peeress in the bench of barons, had tea served by a baboon clad in cold brocade, which her ladyship called My Black. Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester, used to go and take her seat in Parliament in a coach with armorial bearings, behind which stood, their muzzles stuck up in the air, three Cape monkeys in grand livery. A Duchess of Medina-Celi, whose toilet Cardinal Pole witnessed, had her stockings put on by an orang-outang. These monkeys raised in the scale were a counterpoise to men brutalized and bestialized.

- It is very fortunate that kings cannot err. Hence their contradictions never perplex us.

- Not only did the Comprachicos take away his face from the child, they also took away his memory. At least they took away all they could of it; the child had no consciousness of the mutilation to which he had been subjected. This frightful surgery left its traces on his countenance, but not on his mind.

- Sometimes the king went so far as to avow his complicity. These are audacities of monarchical terrorism. The disfigured one was marked with the fleur-de-lis; they took from him the mark of God; they put on him the mark of the king.

- The laws against vagabonds have always been very rigorous in England. England, in her Gothic legislation, seemed to be inspired with this principle, Homo errans fera errante pejor. One of the special statutes classifies the man without a home as "more dangerous than the asp, dragon, lynx, or basilisk."

- Freedom which exists in the wanderer terrified the law.

- It was an immemorial custom in England to tar smugglers. They were hanged on the seaboard, coated over with pitch and left swinging. Examples must be made in public, and tarred examples last longest. The tar was mercy: by renewing it they were spared making too many fresh examples. They placed gibbets from point to point along the coast, as nowadays they do beacons. The hanged man did duty as a lantern. After his fashion, he guided his comrades, the smugglers. The smugglers from far out at sea perceived the gibbets. There is one, first warning; another, second warning. It did not stop smuggling; but public order is made up of such things. The fashion lasted in England up to the beginning of this century. In 1822 three men were still to be seen hanging in front of Dover Castle. But, for that matter, the preserving process was employed not only with smugglers. England turned robbers, incendiaries, and murderers to the same account. Jack Painter, who set fire to the government storehouses at Portsmouth, was hanged and tarred in 1776. L'Abbé Coyer, who describes him as Jean le Peintre, saw him again in 1777. Jack Painter was hanging above the ruin he had made, and was re-tarred from time to time. His corpse lasted—I had almost said lived—nearly fourteen years. It was still doing good service in 1788; in 1790, however, they were obliged to replace it by another. The Egyptians used to value the mummy of the king; a plebeian mummy can also, it appears, be of service.

- Le monologue est la fumée des feux intérieurs de l’esprit.

- Soliloquy is the smoke exhaled by the inmost fires of the soul.

- Part I. Book II. Chapter IV.

- Soliloquy is the smoke exhaled by the inmost fires of the soul.

- A child is protected by the limit of feebleness against emotions which are too complex. He sees the fact, and little else beside. The difficulty of being satisfied by half-ideas does not exist for him. It is not until later that experience comes, with its brief, to conduct the lawsuit of life. Then he confronts groups of facts which have crossed his path; the understanding, cultivated and enlarged, draws comparisons; the memories of youth reappear under the passions, like the traces of a palimpsest under the erasure; these memories form the bases of logic, and that which was a vision in the child's brain becomes a syllogism in the man's.

- The child felt the coldness of men more terribly than the coldness of night. The coldness of men is intentional. He felt a tightening on his sinking heart which he had not known on the open plains. Now he had entered into the midst of life, and remained alone. This was the summit of misery. The pitiless desert he had understood; the unrelenting town was too much to bear.

- At intervals, that we should not become too discouraged, that we may have the stupidity to consent to bear our being, and not profit by the magnificent opportunities to hang ourselves which cords and nails afford, nature puts on an air of taking a little care of man—not to-night, though. The rogue causes the wheat to spring up, ripens the grape, gives her song to the nightingale. From time to time a ray of morning or a glass of gin, and that is what we call happiness! It is a narrow border of good round a huge winding-sheet of evil. We have a destiny of which the devil has woven the stuff and God has sewn the hem.

- The true virtue is common sense—what falls ought to fall, what succeeds ought to succeed. Providence acts advisedly, it crowns him who deserves the crown; do you pretend to know better than Providence? When matters are settled—when one rule has replaced another—when success is the scale in which truth and falsehood are weighed, in one side the catastrophe, in the other the triumph; then doubt is no longer possible, the honest man rallies to the winning side, and although it may happen to serve his fortune and his family, he does not allow himself to be influenced by that consideration, but thinking only of the public weal, holds out his hand heartily to the conqueror. What would become of the state if no one consented to serve it? Would not everything come to a standstill? To keep his place is the duty of a good citizen. Learn to sacrifice your secret preferences. Appointments must be filled, and some one must necessarily sacrifice himself. To be faithful to public functions is true fidelity. The retirement of public officials would paralyse the state. What! banish yourself!—how weak! As an example?—what vanity! As a defiance?—what audacity! What do you set yourself up to be, I wonder? Learn that we are just as good as you. If we chose we too could be intractable and untameable and do worse things than you; but we prefer to be sensible people. Because I am a Trimalcion, you think that I could not be a Cato! What nonsense!