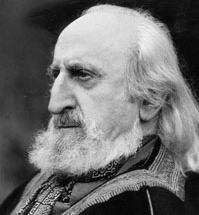

Frithjof Schuon

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Frithjof Schuon (Switzerland, 18 June 1907 – U.S.A., 5 May 1998) was a Swiss metaphysician and spiritual master of German descent, belonging to the Perennialist or Traditionalist School of thought. He was the author of more than twenty works in French on metaphysics, spirituality, the religious phenomenon, anthropology and art, which have been translated into English and many other languages. He was also a painter and a poet.

to actualize in thought the certitudes contained, not in the thinking ego, but in the transpersonal substance of human intelligence."

(Frithjof Schuon, Introduction to Form and Substance in the Religions, World Wisdom, 2002, page viii)Human being[edit]

Origin[edit]

- Original man was not a simian creature barely capable of speaking and standing upright; he was a quasi-immaterial being enclosed in an aura still celestial, but deposited on earth; an aura similar to the "chariot of fire" of Elijah or the "cloud" that enveloped Christ during his ascension. That is to say, our conception of the origin of mankind is based on the doctrine of the projection of the archetypes ab intra; thus our position is that of classical emanationism – in the Neoplatonic or gnostic sense of the term – which avoids the pitfall of anthropomorphism while agreeing with the theological conception of creatio ex nihilo. Evolutionism, for its part, is the very negation of the archetypes and consequently of the divine Intellect; it is therefore the negation of an entire dimension of the real, namely that of form, of the static, of the immutable; concretely speaking, it is as if one wished to make a fabric of the wefts only, omitting the warps.

- To Have a Center. World Wisdom. 2015. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-936597-44-4.

- One must not tire of affirming this: the origin of a creature is not a substance of a material kind, it is a perfect and non-material archetype: perfect, therefore without any need of a transformative evolution; non-material, therefore having its origin in the Spirit, not in matter. Assuredly, there is a trajectory; but this proceeds not from an inert and unconscious substance, but from the Spirit − the matrix of all possibilities − to the earthly result, the creature; and this result issued from the invisible at a cyclic moment when the physical world was still far less separate from the psychic world than in later and progressively more "hardened" periods. When one speaks traditionally of creatio ex nihilo, what is meant, on the one hand, is that creatures do not derive from a pre-existing matter and, on the other, that the "incarnation" of possibilities cannot in any way affect the immutable plenitude of the Principle.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- A classic example of a naive dogma is the Biblical story of creation, followed by that of the first human couple: if we are skeptical, we balk at the childishness of the literal meaning; but if we are intuitive − as every man ought to be − we will be sensitive to the irrefutable truths of the images; we feel that we bear these images within ourselves, that they have a universal and timeless validity. The same observation applies to myths and even to fairy tales: in describing principles − or situations − concerning the universe, they describe at the same time psychological and spiritual realities of the soul; and in this sense it can be said that the symbolisms of religion or of popular tradition are a part of our common experience, both on the surface and in depth.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

Deiformity[edit]

- To say that man is "made in the image of God" means that he represents a central and not a peripheral subjectivity, and consequently a subject which, emanating directly from the Divine Intellect, participates in principle in the power of the latter; man can know all that is real, hence knowable, otherwise he would not be that earthly divinity which in fact he is.

- The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Quest Books. 1993. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8356-0587-8.

- It is in man’s theomorphic nature that in his capacity as man and in God’s creative intention, he cannot be something fragmentary or incomplete − which cuts short the absurdities of transformist evolution − thus that he must be something which is everything, and would be nothing if it were not everything; and it is in this sense that it has been said that man’s fundamental vocation is to "become what he is".

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- Man is a divine manifestation, not in his accidentality and his fallen state, but in his theomorphism and his primordial and principial perfection. He is the "field of manifestation" of the intellect, which reflects the universal Spirit and thereby the divine Intellect; man as such reflects the cosmic totality, the Creation, and thereby the Being of God.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- Moral liberty and intellectual objectivity constitute a priori man’s deiformity.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

Specificities[edit]

- The human being, by his nature, is condemned to the supernatural.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- Objective intelligence, free will, virtuous soul: these are the three prerogatives that constitute man.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- The double mission of man: to know the Absolute from the standpoint of the contingent, and to manifest the Absolute within the contingent.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- It has been said that man is a rational animal; while this formulation is insufficient and ill-sounding, it nonetheless points to an undeniable truth, though in an elliptical fashion, for the rational faculty actually serves to underscore the transcendence of man in relation to the animal. Man is rational because he possesses the Intellect, which by definition has a capacity for the absolute and therefore a sense of the relative; and he possesses the Intellect because he is made "in the image of God", which, moreover, he demonstrates physically by his corporeal form and his cranial form, as well as by his vertical posture, then by language and his productive capacity. Man is a theophany in his form as much as in his faculties.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- One of the keys to understanding our true nature and our ultimate destiny is the fact that the things of this world are never proportionate to the actual range of our intelligence. Our intelligence is made for the Absolute, or else it is nothing; the Absolute alone confers on our intelligence the power to accomplish to the full what it can accomplish and to be wholly what it is. Similarly, in the case of the will, which is no more than a prolongation or complement of the intelligence: the objects it commonly sets out to achieve, or those that life imposes on it, do not measure up to the fullness of its range; only the "divine dimension" can satisfy the thirst for plenitude in our willing or our love.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.

- One of the proofs of our immortality is that the soul − which is essentially intelligence and consciousness − cannot have an end that is beneath itself, namely matter or the mental reflections of matter; the higher cannot be merely a function of the lower, it cannot be merely a means in relation to what it surpasses. Thus it is intelligence in itself − and with it our freedom − which proves the divine scope of our nature and our destiny. Whether people understand it or not, the Absolute alone is proportionate to the essence of our intelligence.

- Understanding Islam. World Wisdom. 1998. p. 92. ISBN 0-941532-24-0.

- The human vocation is to realize that which constitutes man's raison d’être: a projection of God and, therefore, a bridge between earth and Heaven; or a point of view that allows God to see Himself starting from an other-than-Himself, even though this other, in the final analysis, can only be Himself, for God is known only through God.

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 45. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- Human intelligence is essentially objective, hence total: it is capable of disinterested judgment, reasoning, assimilating and deifying meditation, with the help of grace. This attribute of objectivity also belongs to the will − it is this attribute that makes it human − and this is why our will is free, in other words capable of self-transcendence, sacrifice, and ascesis; our willing is not inspired by our desires alone, it is inspired fundamentally by the truth, which is separate from our immediate interests. Likewise for our soul, our sensibility, our capacity for loving: this capacity, being human, is by definition objective and thus disinterested in its essence or in its primordial and innocent perfection; it is capable of goodness, generosity, compassion. This means that it is capable of finding its happiness in the happiness of others, and to the detriment of its own satisfactions; likewise, it is capable of finding its happiness above itself, in its celestial personality, which is not yet completely its own. It is from this specific nature, made of totality and objectivity, that the vocation of man derives, together with his rights and his duties.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- Man is by definition pontifex, "builder of bridges", or "builder of a bridge". For man possesses essentially two dimensions, an outward and an inward; he therefore has the right to both, or else he would not be man, precisely; to speak of a man without surroundings is as contradictory as to speak of a man without a core. On the one hand, we live among the phenomena which surround us and of which we are a part, and on the other hand, our hearts are rooted in God; consequently we must realize as perfect an equilibrium as possible between our life in the world and our life directed toward the Divine. Obviously this second life determines the first and gives it all its meaning; the rights of outwardness depend upon measures which pertain to the inward and which the inward imposes upon us.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.

- God has opened a gate in the middle of creation, and this open gate of the world towards God is man; this opening is God’s invitation to look towards Him, to tend towards Him, to persevere with regard to Him, and to return to Him. And this enables us to understand why the gate shuts at death when it has been scorned during life; for to be man means nothing other than to look beyond and to pass through the gate. Unbelief and paganism are whatever turns its back on the gate; on its threshold light and darkness separate. The notion of Hell becomes perfectly clear when we think how senseless it is − and what a waste and a suicide − to slip through the human state without being truly man, that is, to pass God by, and thus to pass our own souls by, as if we had any right to human faculties apart from the return to God, and as if there were any point in the miracle of the human state apart from the end which is prefigured in man himself; or again: as if God had had no motive in giving us an intelligence which discerns and a will which chooses.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

Body[edit]

- To say that man, and consequently the human body, is "made in the image of God" means a priori that it manifests something absolute and for that very reason something unlimited and perfect. What above all distinguishes the human form from animal forms is its direct reference to absoluteness, starting with its vertical posture; as a result, if animal forms can be transcended − and they are so by man, precisely − such could not be the case for the human form; this form marks not only the summit of earthly creatures, but also, and for this very reason, the exit from their condition, or from the samsāra as Buddhists would say. To see man is to see not only the image of God, but also a door open towards bodhi, liberating enlightenment; or, let us say, towards a blessed centering in the divine proximity.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- Being absolute, the supreme Principle is ipso facto infinite; the masculine body accentuates the first aspect, and the feminine body the second. On the basis of these two hypostatic aspects, the divine Principle is the source of all possible perfection; in other words, being the Absolute and the Infinite, It is necessarily also Perfection or the Good. Now each of the two bodies, the masculine and the feminine, manifests modes of perfection which their respective gender evokes by definition; indeed, all cosmic qualities are divided into two complementary groups: the rigorous and the gentle, the active and the passive, the contractive and the expansive. The human body is an image of Deliverance: now the liberating way maybe either "virile" or "feminine", although it is not possible to have a strict line of demarcation between the two modes, for man (homo, anthropos) is always man; the non-material being that was the primordial androgyne survives in each of us.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- A priori, virility refers to the Principle, and feminity to Manifestation; but in an altogether different respect, that of complementarity in divinis, the masculine body expresses transcendence, and the feminine body, immanence; immanence being close to love, and transcendence to knowledge.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 81-82. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- Much could be said about the abstract and concrete symbolism of the different regions or parts of the body. A symbolism is abstract inasmuch as it signifies a principial reality; it is concrete inasmuch as it communicates the nature of this reality, that is, inasmuch as it makes it present to our experience. One of the most striking characteristics of the human body is the breast, which is a solar symbol, the accentuation differing according to sex: noble and glorious radiation in both male and female, but manifesting power in the first case and generosity in the second − the power and generosity of pure Being.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

Ego[edit]

- The ego is at the same time a system of images and a cycle; it is something like a museum, and a unique and irreversible journey through that museum. The ego is a moving fabric made of images and tendencies; the tendencies come from our own substance, and the images are furnished by the environment. We put ourselves into things, and we place things in ourselves, whereas our true being is independent of them.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.

- We live at the same time in the body, the head, and the heart, so that we may sometimes ask ourselves where the genuine "I" is located; in fact the ego proper, the empirical "I", has its sensory seat in the brain, but it readily gravitates toward the body and tends to identify itself with it, whereas the heart is the symbolic seat of the Self, of which we may or may not be aware, but which is our true existential, intellectual, and therefore universal center.

- Gnosis: Divine Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-933316-18-5.

- There are in man two subjects − or two subjectivities − with no common measure and with opposite tendencies, though there is also, in some respect, coincidence between the two. On the one hand, there is the anima or empirical ego, woven out of objective as well as subjective contingencies, such as memories and desires; on the other hand, there is the spiritus or pure Intelligence, whose subjectivity is rooted in the Absolute, so that it sees the empirical ego as being no more than a husk, that is, something outward and foreign to the true "my-self", or rather "One-self", at once transcendent and immanent.

- Form and Substance in the Religions. World Wisdom. 2002. p. 243. ISBN 0-941532-25-9.

- When the soul has recognized that its true being is beyond this phenomenal nucleus which is the empirical ego and when it willingly holds fast to the Center − and this is the chief virtue, poverty, or effacement, or humility − the ordinary ego appears to the soul as outward to itself, and the world, on the contrary, appears to it as its own prolongation; all the more so since it feels itself everywhere in the Hand of God.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

Character[edit]

- In spirituality more than in any other domain, it is important to understand that a person’s character is part of his intelligence: without a good character − a normal and therefore noble character −, intelligence, even that of a metaphysician, is partially inoperative, for the simple reason that full knowledge of what lies outside us requires a full knowledge of ourselves. A person’s character is, on the one hand, what he wills, and on the other hand, what he loves; will and sentiment prolong intelligence; like the intelligence − which obviously penetrates them − they are faculties of adequation. To know the Sovereign Good really is, ipso facto, on the one hand to will what brings us closer to it and on the other hand to love what bears witness to it; every virtue in the final analysis derives from this will and this love. Intelligence that is not accompanied by virtues gives rise to an as it were planimetric knowledge: it is as if one were to grasp but the circle or the square, and not the sphere or the cube.

- To Have a Center. World Wisdom. 2015. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-936597-44-4.

Intellect[edit]

- The Intellect constitutes the raison d’être of the human condition.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- Reason perceives the general and proceeds by logical operations, whereas Intellect perceives the principial − the metaphysical − and proceeds by intuition.

- Gnosis: Divine Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-933316-18-5.

- The Divine Order is absolute with respect to human relativity, although not with respect to the pure Intellect, which transcends all relativity − effectively or potentially − otherwise we would not even have the notion of the Absolute.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- What animals and man have in common is, first of all, sensorial and instinctual intelligence, then the faculties of the senses, and finally basic feelings. What is proper to man alone is the intellect open to the Absolute; and also, owing to that very fact, reason, which extends the Intellect in the direction of relativity; and consequently it is the capacity for integral knowledge, for sacralization, and for ascension. Man shares with animals the wonder of subjectivity − but strangely a wonder that is not understood by the evolutionists; however, the subjectivity of animals is only partial, whereas that of man is total; the sense of the Absolute coincides with totality of intelligence.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- If it were necessary or useful to prove the Absolute, the objective and transpersonal character of the human Intellect would be a sufficient testimony, for this Intellect is the indisputable sign of a purely spiritual first Cause, a Unity infinitely central but containing all things, an Essence at once immanent and transcendent. It has been said more than once that total Truth is inscribed in an eternal script in the very substance of our spirit; what the different Revelations do is to "crystallize" and "actualize", in different degrees according to the case, a nucleus of certitudes that not only abides forever in the divine Omniscience, but also sleeps by refraction in the "naturally supernatural” kernel of the individual, as well as in that of each ethnic or historical collectivity or the human species as a whole.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.

- Human intelligence, or the intellect, cannot disclose to us the aseity of the Absolute, and no sensible person would ask this of it; the intellect can give us points of reference, and this is all that is necessary as regards discriminative and introductory knowledge, the knowledge that can be expressed through words. But the intellect is not only discriminative, it is also contemplative, hence unitive, and in this respect it cannot be said to be limited, any more than a mirror limits the light reflected in it; the contemplative dimension of the intellect coincides with the ineffable.

- The Play of Masks. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-94153214-3.

Intelligence[edit]

- Man's thought, or his intelligence, is made for the divine Truth, and man's heart, or his being, is made for the divine Presence.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 4. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- It is logical that those who rely exclusively upon Revelation and not upon Intellection should be inclined to discredit intelligence, whence the notion of "intellectual pride". They are justified when it is a question of "our" intelligence "alone", but not when it is a question of intelligence in itself, inspired by the Intellect which is ultimately divine. For the sin of the philosophers consists, not in relying upon intelligence as such, but in relying upon their own intelligence, hence upon intelligence severed from its supernatural roots.

- The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Quest Books. 1993. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8356-0587-8.

- Normally and primordially, human intelligence realizes a perfect equilibrium between the intelligence of the brain and that of the heart: the first is the rational capacity with the various skills connected to it; the second is intellectual or spiritual intuition, or in other words it is the eschatological realism that permits one to choose the saving truth even without any mental speculation. Cardiac intelligence, even when reduced to its minimum, is always right; it is from this that faith is derived when it is profound and unshakeable, and such is the intelligence of a great number of saints.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- Consciousness of the Absolute is the prerogative of human intelligence, and also its aim.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

Intellection (intellectual intuition)[edit]

- Intellectual genius should not be confused with the mental acuity of logicians: intellectual intuition comprises in its essence a contemplativity that is in no way part of the rational capacity, this capacity being logical rather than contemplative; now it is contemplative power, receptivity toward the uncreated Light, the opening of the Eye of the heart, which distinguishes transcendent intelligence from reason.

- Gnosis: Divine Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-933316-18-5.

- Whereas metaphysics proceeds wholly from intellectual intuition, religion proceeds from Revelation. The latter is the Word of God spoken to His creatures, whereas intellectual intuition is a direct and active participation in divine Knowledge and not an indirect and passive participation, as is faith. In other words, in the case of intellectual intuition, knowledge is not possessed by the individual insofar as he is an individual, but insofar as in his innermost essence he is not distinct from his Divine Principle. Thus metaphysical certitude is absolute because of the identity between the knower and the known in the Intellect.

- The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Quest Books. 1993. p. xxx. ISBN 978-0-8356-0587-8.

- Direct and supra-mental intellection is in reality a "remembering" and not an "acquisition": intelligence in this realm does not take cognizance of something located in principle outside itself, but all possible knowledge is on the contrary contained in the luminous substance of the Intellect − which is identified with the Logos by "filiation of essence" − so that the "remembering" is nothing other than an actualization, thanks to an occasional external cause or an internal inspiration, of a given eternal potentiality of the intellective substance.

- Gnosis: Divine Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-933316-18-5.

- If every man possessed intellect, not merely in a fragmentary or virtual state, but as a fully developed faculty, there would be no Revelations, because total intellection would be a natural thing; but as this has not been so since the end of the Golden Age, Revelation is not only necessary, but even normative with regard to individual intellection, or rather with regard to its formal expression. No intellectuality is possible outside a revealed mode of expression, a scriptural or oral tradition, although intellection can occur, as an isolated miracle, wherever the intellective faculty exists; but an intellection outside tradition will have neither authority nor efficacy. Intellection has need of occasional causes in order to become fully aware of itself and exercised without constraints; therefore in milieus that are practically speaking deprived of Revelation − or forgetful of the sapiential meanings of the revealed Word − intellectuality generally exists only in a latent state; even where it is still affirmed despite everything, perceived truths are made inoperative by their overly fragmentary character and by the mental chaos which surrounds them. For the intellect, Revelation is like a principle of actualization, expression and control; in practice the revealed "letter" is indispensable in intellectual life.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

God[edit]

Outline[edit]

- The word "God" does not and cannot admit of any restriction, for the simple reason that God is "all that is purely principial", hence also − and a fortiori − "Beyond-Being"; one may not know this or may deny it, but it cannot be denied that God is "That which is supreme", hence That which nothing can surpass.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- There are three great theophanies, or three hypostases, which are, in descending order: firstly, Beyond-Being or the Self, Absolute Reality, Âtmâ; secondly, Being or the Lord, who creates, reveals and judges; and thirdly, the manifested Divine Spirit, which Itself possesses three modes: the universal or archangelic Intellect, the Man-Logos, who reveals in a human language, and the Intellect in ourselves, which is "neither created or uncreated", and which confers upon the human species its central, axial and "pontifical" rank, one which is virtually divine with regard to other creatures.

- Form and Substance in the Religions. World Wisdom. 2002. p. 95. ISBN 0-941532-25-9.

- Some will no doubt point out that Buddhism proves that the notion of God has nothing fundamental about it and that one can very well dispense with it in both metaphysics and spirituality; they would be right if Buddhists did not possess the idea of the Absolute or of transcendence, or of immanent Justice with its complement, Mercy; this is all that is needed to show that Buddhism, though it does not possess the word − or not our word − nonetheless possesses the reality itself.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

- Divine anthropomorphism responds to human theomorphism: if God can manifest Himself in human modalities, it is because man is "made in the image of God", and this is the very reason for man’s existence and for the cosmic miracle that he is.

- Christianity / Islam. World Wisdom. 2008. p. 105-106. ISBN 978-1-933316-49-9.

- To say that God is "unknowable" is, on the one hand simply a manner of speaking which intends to emphasize that reason is limited in principle, and on the other hand that the intellect, accidentally obscured, is limited in fact. To possess total Knowledge is to be possessed by it: it is to be a "knower by God" (ʿārif bi ʾLlāh), in the sense that God reveals Himself to the extent that He is, in us, both the Subject and the Object of Knowledge.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- Certainly, God is ineffable, nothing can describe Him or enclose Him in words; but on the other hand, truth exists, that is to say that there are conceptual points of reference which provide a sufficient expression of the nature of God; otherwise our intelligence would not be human, which amounts to saying that it would not exist, or simply that it would be inoperative with respect to what constitutes the reason for man’s existence. God is both unknowable and knowable, a paradox which implies − on pain of absurdity − that the relationships are different, first of all on the plane of mere thought and then in virtue of everything that separates mental knowledge from that of the heart; the first is a "perceiving", and the second a "being". "The soul is all that which it knows", said Aristotle; one must add that the soul is able to know all that which it is; and that in its essence it is none other than That which is, and That which alone is.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- In pure theosophy there is no question of wishing to remove from God His mysteries by means of unveilings and specifications; for however acute our discernments, the divine mystery remains complete by reason of the Infinitude of the Real.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- The man who rejects religion because, when taken literally, it sometimes seems absurd − since truths have to be selectively chosen and parceled out in a manner required by the formal crystallization and by the adaptation to an intellectually minimal collective mentality − such a man overlooks one essential thing, despite the logic of his reaction: namely, that the imagery, contradictory though it may be at first sight, nonetheless conveys information that in the final analysis is coherent and even dazzlingly evident for those who are capable of having a presentiment of it or of grasping it. It is true that there is, a priori, a contradiction between an omniscient, omnipotent, and infinitely good God who created man without foreseeing the fall; who grants him too great a freedom with respect to his intelligence, or too small an intelligence in proportion to his freedom; who finds no other means of saving man than to sacrifice His own Son, and doing so without the immense majority of men being informed of this − and being able to be informed of it in time − when in fact this information is the conditio sine qua non of salvation; who after having powerfully revealed that He is One, waits for centuries before revealing that He is Three; who condemns man to an eternal hell for temporal faults; a God who on the one hand "wants" man not to sin, and on the other "wills" that a particular sin be committed, or who predestines man to a particular sin, on the one hand, and, on the other, punishes him for having committed it; or again, a God who gives us intelligence and then forbids us to use it, as practically every fideism would have it; and so on. But whatever may be the contradiction between an omniscient and omnipotent God and the actions attributed to Him by scriptural symbolism and anthropomorphist, voluntaristic, and sentimental theology, there is, beyond all this imagery − whose contradictions are perfectly resolvable in metaphysics − an Intelligence, or a Power, which is fundamentally good and which − with or without predestination − is disposed to saving us from a de facto distress, on the sole condition that we resign ourselves to following its call; and this reality is a "categorical imperative" which is so to speak in the air we breathe and independent of all requirements of logic and all need for coherence.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 4-6. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- When God is absent, pride fills the void.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

Proofs[edit]

- In the spiritual order a proof is of assistance only to the man who wishes to understand and who, because of this wish, has in some measure understood already; it is of no practical use to one who, deep in his heart, does not want to change his position and whose philosophy merely expresses this desire.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

- There is nothing more contradictory than a cerebral intelligence opposing itself to cardiac intelligence, whether it be to deny the possibility of knowledge or to deny the ultimate Knower: how can one not feel instinctively, "viscerally", existentially, that one cannot be intelligent, even very relatively so, without an Intelligence "in itself" that is both transcendent and immanent, and not grasp that subjectivity by itself is an immediate and quasi-fulgurating proof of the Omniscient, a proof almost too blindingly evident to be able to be formulated in words?

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- The fundamental solution to the problem of the credibility of religious axioms, and consequently the quintessence of the proofs of God, lies in the ontological correspondence between the macrocosm and the microcosm, that is, in the fact that the microcosm has to mirror the macrocosm; in other words, the subjective dimension, taken in its totality, coincides with the objective dimension, from which the religious and metaphysical truths derive in the first place. What matters is to actualize this coincidence, and this is what Revelation does, in principle or de facto, by awakening, if not always direct intellection, at least the indirect intellection which is faith; credo ut intelligam.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

Reverential fear and love[edit]

- If we must love God, and love him more than ourselves and our neighbor, it is because love exists before us and because we are issued from it; we love by virtue of our very existence.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- To love God does not mean to cultivate a sentiment − that is to say, something we enjoy without knowing whether God enjoys it − but to eliminate from the soul what prevents God from entering it.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- Love of God is firstly the attachment of the intelligence to the Truth, then the attachment of the will to the Good, and finally the attachment of the soul to the Peace that is given by the Truth and the Good.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- One cannot love God without fearing him, any more than one can love one's neighbor without respecting him; not to fear God is to prevent Him showing mercy.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- To fear God is first of all to see, on the level of action, consequences in causes, sanction in sin, suffering in error; to love God is first to choose God, that is to say, to prefer what brings one nearer Him over what estranges from Him.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- Without fear of God as a basis, nothing is possible spiritually, for the absence of fear is a lack of self-knowledge.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- The fear of God is not in any way a matter of feeling any more than is the love of God; like love, which is the tendency of our whole being toward transcendent Reality, fear is an attitude of the intelligence and the will: it consists in taking account at every moment of a Reality which infinitely surpasses us, against which we can do nothing, in opposition to which we could not live, and from the teeth of which we cannot escape.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- Love of God is something universal: the term "love" designates not only a path depending on will and feeling, but also − and this is its broadest meaning − every path insofar as it attaches us to the Divine; "love" is everything which makes us prefer God to the world and contemplation to earthly activity, wherever this alternative has a meaning. The best love will be, not that which most resembles what the word "love" can evoke in us a priori, but that which will attach us most steadfastly or most profoundly to Reality; to love God is to keep oneself near to Him, in the midst of the world just as beyond the world; God wants our souls, whatever may be our attitudes or our methods.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

Beauty[edit]

- Beauty, whatever use man may make of it, belongs fundamentally to its Creator, who through it projects into the world of appearances something of His being.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- The beautiful is not that which we love and because we love it, but that which by its objective value obliges us to love it.

- Sufism: Veil and Quintessence. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-933316-28-4.

- Beauty is a reflection of divine beatitude; and since God is Truth, the reflection of His beatitude will be that blend of happiness and truth found in all beauty.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- The beauty of the sacred is a symbol or a foretaste of, and sometimes a means for, the joy that God alone procures.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- The interiorization of beauty presupposes nobility of soul and at the same time produces it.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 59. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- The cosmic, and more particularly the earthly, function of beauty is to actualize in the intelligent and sensitive creature the Platonic recollection of the archetypes, and thus open the way towards the luminous Night of the one and infinite Essence.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- The perception of beauty, being a strict adequation and not a subjective illusion, essentially entails, on the one hand, a sense of satisfaction for the intelligence, and on the other, a sentiment at once of security, infinity, and love. Of security: because beauty is unitive and excludes, by means of a kind of musical evidence, the fissures of doubt and worry; of infinity: because beauty, by its very musicality, melts all hardness and limitations, thus freeing the soul from its constrictions, be it only in a minute and remote manner; of love: because beauty conjures love, that is to say, it draws the soul to union and hence to unitive extinction.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- Beauty is a message that implies a reciprocity and a commitment: it implies a reciprocity between God and man, and a commitment from man to God. In and by beauty, God gives us a message of His nature; He reveals for our sake an archetype and an essence. Beauty is a manifestation of Mercy. Man’s gratitude is that, having glimpsed divine Beauty, he gives himself to God in his heart; to give oneself to God is the response proportionate to the earthly beauty in which God, in revealing Mercy, has given Himself to man.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

Spiritual life[edit]

Outline[edit]

- The chief difficulty of the spiritual life is to maintain a simple, qualitative, heavenly position in a complex, quantitative, earthly setting.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 20. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- The worldly or imperfect man journeys through life as if on a long road; if he is a believer, he sees God above him in the far distance, and also at the end of this road. However the spiritual man stands in God, and life passes before him like a stream.

- Vers l’Essentiel : lettres d’un maître spirituel. Les Sept Flèches. 2013. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-97003-258-8.

- It is less the pettinesses of the world that poison us than the fact of thinking of them too much. We should never lose our awareness of the luminous and calm grandeur of the Sovereign Good, which dissolves all the knots of this world here below.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- We are agitated because we believe we have a motive for being so, that is to say, we take into account the accidents only, instead of looking toward the Substance; phenomena draw us into a vicious circle and make us forget that we bear within ourselves that which we are seeking outside.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 20. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- There are two moments in life which are everything, and these are the present moment, when we are free to choose what we wish to be, and the moment of death, when we no longer have any choice and the decision belongs to God. Now if the present moment is good, death shall be good; if we are with God now − in this present which is ceaselessly being renewed but which always remains this one and only moment of actuality − God shall be with us at the moment of our death. The remembrance of God is a death in life; it shall be a life in death.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- We must distinguish between natural life, which is centrifugal, and supernatural life, which is centripetal; the first pulls the soul away from God and drives it into the world, whereas the second draws the soul away from the world and leads it back to God. Natural or centrifugal life comprises one effect which is dispersion and another which is compression: the profane or worldly man loses himself in the multitude of things, on the one hand, and becomes hardened in his passional attachments, on the other hand. The supernatural life, on the contrary, comprises one effect which is dilation and another which is concentration: the spiritual man is dilated towards the Interior, on the one hand, and is united to the Unique on the other hand, the one being the function of the other.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 15. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- We are surrounded by a world of tumult and incertitude; and there are sudden encounters with things that are surprising, incomprehensible, absurd or disappointing. But these things have no right to be problems for us, if only because every phenomenon has its causes, whether we know them or not. Whatever may be the phenomena and whatever their causes, there is always That Which Is; and That Which Is, lies beyond the world of tumult, contradictions, and disappointments. That Which Is can be troubled and diminished by nothing; It is Truth, Peace, and Beauty. Nothing can tarnish It, and no one can take It from us.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

Truth[edit]

- Truth is the raison d’être for man’s existence; it constitutes our grandeur and reveals to us our smallness.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- Truth and Holiness: all values are in these two terms; all that we must love and all that we must be.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- What the virtues are to existential perfection, truths are to intellectual perfection; virtue is essentially simplicity, inward beauty, generosity, whereas truth, for its part, lies entirely in the discernment between the Real and the illusory or between the Absolute and the contingent.

- The Transfiguration of Man. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-94153219-8.

- The first of the virtues is veracity, for without truth we can do nothing. The second virtue is sincerity, which consists in drawing the consequences of what we know to be true, and which implies all the other virtues; for it is not enough to acknowledge the truth objectively, in thought, it must also be assumed subjectively, in acts, whether outward or inward. Truth excludes heedlessness and hypocrisy as much as error and lying.

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 113. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- One cannot state too clearly that a doctrinal formulation is perfect, not because it exhausts the infinite Truth on the plane of logic, which is impossible, but because it realizes a mental form capable of communicating, to whoever is intellectually apt to receive it, a ray of that Truth, and thereby a virtuality of the total Truth. This explains why the traditional doctrines are always apparently naive, at least from the point of view of philosophers − that is to say, of men who do not understand that the goal and sufficient reason of wisdom do not lie on the plane of its formal affirmation; and that, by definition, there is no common measure and no continuity between thought, whose operations have no more than a symbolic value, and pure Truth, which is identical with That which "is" and thereby includes him who thinks.

- The Eye of the Heart. World Wisdom. 2021. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-93659770-3.

Faith[edit]

- Faith is to say "yes" to God. When man says "yes" to God, God says "yes" to man.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- If faith is a mystery, it is because its nature is inexpressible in the measure that it is profound, for it is not possible to convey fully by words this vision which is still blind, and this blindness which already sees.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- It could be said that faith is that something which makes intellectual certitude become holiness; or which is the realizatory power of certitude.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- The fact that spiritual realism, or faith, pertains to the intelligence of the heart and not to that of the mind, enables one to understand that in spirituality, the moral qualification takes precedence over the intellectual qualification, and by far.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- Humanly, no one escapes the obligation to "believe in order to be able to understand" (credo ut intelligam).

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- In the elementary sense of the word, faith is our assent to a truth that transcends us; but spiritually speaking, it is our assent, not to transcendent concepts, but to immanent realities, or to Reality as such; now this Reality is our very substance.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- A man may have metaphysical certainty without having "faith", that is, without this certainty residing in his soul as a continuously active presence. But if metaphysical certainty suffices on doctrinal grounds, it is far from being sufficient on the spiritual plane, where it must be completed and brought to life by faith. Faith is nothing other than the adherence of our whole being to Truth, whether we have a direct intuition of this Truth or an indirect notion.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- Faith is peace of heart arising from an almost boundless certainty, thus by its very nature falling outside the jurisdiction of doubt; human intelligence is made for transcendence, for otherwise it would be nothing more than an increase in animal intelligence. Apart from the content that completes it, faith is our disposition to know before knowing; indeed this disposition is already knowledge in that it is derived from innate wisdom, which it is precisely the function of the revealed content of faith to revive.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

Sense of the sacred[edit]

- The sacred is an apparition of the Center, it immobilizes the soul and turns it towards the Inward.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- Love of the sacred implies love of God, and inversely, the sacred is the perfume of Heaven.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 60. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- The sense of the sacred is the capacity to perceive, or feel, the presence of the Celestial in earthly symbols, whether sacramental or natural; and this implies the sense of dignity as well as of devotion.

- La conscience de l’Absolu. Hozhoni. 2016. p. 57. ISBN 978-2-37241-020-5.

- To have a sense of the sacred is to be aware that all qualities or values not only proceed from the Infinite but also attract towards It.

- The Play of Masks. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-94153214-3.

- The sacred introduces a quality of the absolute into relativities and confers on perishable things a texture of eternity.

- Understanding Islam. World Wisdom. 1998. p. 45. ISBN 0-941532-24-0.

- The sense of the sacred, or the love of sacred things − whether of symbols or modes of Divine Presence − is a conditio sine qua non of Knowledge, which engages not only our intelligence, but all the powers of our soul; for the Divine All demands the human all. The sense of the sacred, which is none other than the quasi-natural predisposition to the love of God and the sensitivity to theophanic manifestations or to celestial perfumes − this sense of the sacred essentially implies both the sense of beauty and the tendency toward virtue; beauty being as it were outward virtue, and virtue, inward beauty. It also implies the sense of the metaphysical transparency of phenomena, that is, the capacity of grasping the principial within the manifested, the uncreated within the created.

- The Transfiguration of Man. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-94153219-8.

- The "pneumatic" is the man in whom the sense of the sacred takes precedence over other tendencies, whereas in the case of the "psychic" it is the attraction of the world and the accentuation of the ego that take priority, without mentioning the "hylic" or "somatic", who sees in sensory pleasure an end in itself. It is not a particularly high degree of intelligence that constitutes initiatic qualification; it is a sense of the sacred − or the degree of this sense − with all the moral and intellectual consequences it implies. The sense of the sacred draws one away from the world and at the same time transfigures it.

- Sufism: Veil and Quintessence. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-933316-28-4.

Trials[edit]

- Every injustice that we suffer at the hands of men is at the same time a trial that comes to us from God.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- Man has the right not to accept an injustice − major or minor − from men, but he does not have the right not to accept it as a trial coming from God. He has the right − for it is human − to suffer from an injustice insofar as he cannot rise above it, but he must make an effort to do so; in no case has he the right to plunge himself into a pit of bitterness, for such an attitude leads to hell. Man has no interest, primarily, in overcoming an injustice; he has an interest primarily in saving his soul and in winning Heaven. Thus it would be a bad bargain to obtain justice at the price of our ultimate interests, to win on the side of the temporal and to lose on the side of the eternal, which is what man seriously risks when concern for his rights deteriorates his character or reinforces its faults.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- To accept a trial is to thank God for it, with the understanding that it permits us a victory, a detachment with regard to the world and with regard to the ego.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- Man has the duty to resign himself to the will of God, but by the same token he has the right to transcend spiritually the suffering of the soul to the extent that this is possible for him; and this, precisely, is not possible without a prior attitude of acceptance and resignation, which alone brings out fully the serenity of the intelligence and which alone opens the soul to help from Heaven.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- First of all one has to answer the question of why the painful experiences that man must undergo are called "trials". We would reply that these experiences are trials in relation to our faith, which indicates that with regard to troubling or painful experiences we have duties resulting from our human vocation; in other words, we must prove our faith in relation to God and in relation to ourselves. In relation to God, by our intelligence, our sense of the absolute, and thus our sense of relativities and proportions; and in relation to ourselves, by our character, our resignation to destiny, our gratitude. There are in fact two ways to overcome the traces that evil, or more precisely suffering, leaves in the soul: these are, firstly, our awareness of the Sovereign Good, which coincides with our hope to the extent that this awareness penetrates us; and secondly, our acceptance of what, in religious language, is called the "will of God"; and assuredly it is a great victory over oneself to accept a destiny because it is God's will and for no other reason.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

Happiness[edit]

- In order to be happy, man must have a center; now this center is above all the certitude of the One. The greatest calamity is the loss of the center and the abandonment of the soul to the caprices of the periphery. To be man is to be at the center; it is to be center.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- The stability of happiness depends − quite apart from any question of destiny − not only on the beauty and wisdom of our attitude but also, and above all, on an opening towards Heaven which confers upon the experience of happiness a life continually renewed. One must realize in earthly mode that which will be realized in heavenly mode; this is the very definition of nobility of character.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- Beauty, and the love of beauty, give to the soul the happiness to which it aspires by its very nature. If the soul wishes to be happy in an unconditional and permanent fashion, it must bear the beautiful within itself; now the soul can only do this through realizing virtue, which we could also term goodness or piety.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- Happiness is religion and character; faith and virtue. It is a fact that man cannot find happiness within his own limits; his very nature condemns him to surpass himself, and in surpassing himself, to free himself.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- One of the first conditions of happiness is the renunciation of the superficial and habitual need to feel happy. But this renunciation cannot spring from the void; it must have a meaning, and this meaning cannot but come from above, from what constitutes our raison d'être. In fact, for too many men, the criterion of the value of life is a passive feeling of happiness which is determined a priori by the outer world; when this feeling does not occur or when it fades − which may have subjective as well as objective causes − they become alarmed, and are as if possessed by the question: "Why am I not happy as I was before?" and by the awaiting of something that could restore their feeling of being happy. All this, it is unnecessary to stress, is a perfectly worldly attitude, hence incompatible with the least of spiritual perspectives. To become enclosed in an earthly happiness is to create a barrier between man and Heaven.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

Sacred art[edit]

- Sacred art helps man find his own center, that kernel whose nature is to love God.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- Apart from its purely didactic role, the essential function of sacred art is to bring Substance − at once single and inexhaustible − into the world of accident and to bring accidental consciousness back to Substance. We could also say that sacred art brings Being into the world of existence, action, or becoming, or that in a certain fashion it brings the Infinite into the finite world, or Essence into the world of forms; thus it suggests a continuity proceeding from the one to the other, a path starting from appearance or accident and issuing into Substance or its celestial reverberations.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

- No art in itself is a human creation; however, what distinguishes sacred art is that its essential content is a revelation, that it manifests a properly sacramental form of heavenly reality, such as the icon of the Virgin and Child, painted by an angel, or by St Luke inspired by an angel, and the icon of the Holy Face, which dates back to the Holy Shroud and St Veronica; or such as the statue of Shiva dancing, or the painted or carved images of the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and Taras.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- [In sacred art], true genius can develop without making innovations: it attains perfection, depth and power of expression almost imperceptibly by means of the imponderables of truth and beauty ripened in that humility without which there can be no true greatness.

- Language of the Self. World Wisdom. 1999. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-94153226-6.

Spiritual path[edit]

Outline[edit]

- In fact, what separates man from divine Reality is but a thin partition: God is infinitely close to man, but man is infinitely far from God. This partition, for man, is a mountain; man stands before a mountain which he must remove with his own hands. He digs away the earth, but in vain, the mountain remains; man however goes on digging, in the name of God. And the mountain vanishes. It was never there.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- The intelligence may well affirm metaphysical and eschatological truths; the imagination − or the subconscious − continues to believe firmly in the world, neither in God nor in the hereafter; every man is a priori hypocritical. The path is precisely the passage from natural hypocrisy to spiritual sincerity.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- To transcend oneself: this is the great imperative of the human condition; and there is another that anticipates it and at the same time prolongs it: to dominate oneself. The noble man is one who dominates himself; the holy man is one who transcends himself. Nobility and holiness are the imperatives of the human state.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- In fact, if metaphysical knowledge remains purely mental, it is worth practically nothing; knowledge is of value only on condition that it be prolonged in both love and will. Consequently, the goal of the way is first of all to mend this hereditary break, and then − on that foundation − to bring about an ascension towards the Sovereign Good, which, in virtue of the mystery of immanence, is our own true Being.

- The Play of Masks. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-94153214-3.

- The essential function of human intelligence is discernment between the Real and the illusory or between the Permanent and the impermanent, and the essential function of the will is attachment to the Permanent or the Real. This discernment and this attachment are the quintessence of all spirituality; carried to their highest level or reduced to their purest substance, they constitute the underlying universality in every great spiritual patrimony of humanity, or what may be called the religio perennis; this is the religion to which the sages adhere, one which is always and necessarily founded upon formal elements of divine institution.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 119-120. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.

- Among the qualities indispensable for spirituality in general, we shall first mention a mental attitude that for want of a better term could be designated by the word "objectivity": this is a perfectly disinterested attitude of the intelligence, hence one that is free from ambition and bias and thereby accompanied by serenity. Secondly, we would mention a quality concerning the psychic life of the individual: this is nobility, or the capacity of the soul to rise above all things that are petty and mean; basically this is a discernment, in psychic mode, between the essential and the accidental, or between the real and the unreal. Finally, there is the virtue of simplicity: man is freed from all unconscious tenseness stemming from self‑love; towards creatures and things he has a perfectly original and spontaneous attitude, in other words, he is without artifice; he is free from all pretension, ostentation, or dissimulation; in a word, he is without pride. Every spiritual method demands above all an attitude of poverty, humility, and simplicity or effacement, an attitude that is like an anticipation of Extinction in God.

- The Eye of the Heart. World Wisdom. 2021. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-93659770-3.

Esoterism[edit]

- Esoterism as such is metaphysics, to which is necessarily joined an appropriate method of realization. But the esoterism of a particular religion − of a particular exoterism precisely − tends to adapt itself to this religion and thereby enter into theological, psychological and legalistic meanders foreign to its nature, while preserving in its secret center its authentic and plenary nature, but for which it would not be what it is.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- Esoteric truth is a two-edged sword: there are men who lose God because they are ignorant of this truth, which alone would save them, and there are others who think they understand it and forge for themselves an illusory and arrogant faith, which they put practically in place of God.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- Knowledge of the various traditional worlds, thus of the relativity of doctrinal formulations and formal perspectives, reinforces the need for essentiality on the one hand and universality on the other; and the essential and the universal are all the more imperative because we live in a world of philosophical supersaturation and spiritual disintegration.

- Understanding Islam. World Wisdom. 1998. p. 101-102. ISBN 0-941532-24-0.

- Esoterism comprises four principal dimensions: an intellectual dimension, represented by doctrine; a volitive or technical dimension, which encompasses the direct and indirect means of the way; a moral dimension, which concerns the intrinsic and extrinsic virtues; and an aesthetic dimension, to which pertain symbolism and art from both the subjective and objective point of view.

- Esoterism as Principle and as Way. World Wisdom. 2019. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-93659765-9.

- There is no theophany that is not prefigured in the very constitution of the human being, made as it is "in the image of God"; and esoterism aims at actualizing what is divine in this mirror of God that is man.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- The spiritual anthropology of authentic esoterism starts from the idea that man is defined by a total and "deiform" intelligence, whereas the common religion readily defines man as "sinner," "slave," even "nothing"; hence in accordance with the "fall" or with creaturely limitation alone, rather than with his inalienable substance or, consequently, with the "divine content".

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 91-92. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- The whole question is knowing whether man possesses a "pre-logical" intuition of Substance or whether he is fundamentally bound up with accidentality; in the first case his intelligence is made for gnosis, and arguments − or imagery − confined to the accidental will ultimately have no hold upon him. For the average man, existence begins with man placed on earth: there is space, and there are things; there is "I" and "other"; we want this, and another wants that; there is good and evil, reward and punishment, and above all this there is God with His unfathomable wishes. But for the born contemplative, everything begins with Truth, which is sensed as an underlying and omnipresent Being; other things can be fully comprehended only through it and in it; outside of it the world is no more than an unintelligible dream. First there is Truth, the nature of things; then there are the consciousnesses that are its receptacles: man is before all else a consciousness in which the True is reflected and around which the True or the Real manifests itself in an endless play of crystallizations. For the contemplative, phenomena and events do not constitute a compact and naive postulate; they are intelligible or bearable only in connection with the initial Truth.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

Metaphysics[edit]

- Metaphysics is the science of the Absolute or the true nature of things.

- Logic and Transcendence. World Wisdom. 2009. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-933316-73-4.

- The content of the universal and primordial doctrine is the following, expressed in Vedantic terms: "Brahma is Reality; the world is appearance; the soul is not other than Brahma". These are the three great theses of integral metaphysics; one positive, one negative, one unitive.

- (1995)"Norms and Paradoxes in Spiritual Alchemy". Sophia: The Journal of Traditional Studies 1 (1): 8.

- Gnosis is essentially the path of the intellect and thus of intellection; the motive force of this path is above all intelligence, not will and sentiment as is the case in the Semitic monotheistic mysticisms—including average Sufism. Gnosis is characterized by its recourse to pure metaphysics: the distinction between Ātmā and Māyā and the consciousness of the potential identity between the human subject, jīvātmā, and the Divine Subject, Paramātmā.

- To Have a Center. World Wisdom. 2015. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-936597-44-4.

- Metaphysics intends to furnish dialectically only reference points; it offers − and this is its entire reason for being − a system of perfectly sufficient keys, through a language that cannot be other than indicative and elliptical.

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 21. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- The principal cause of a lack of metaphysical understanding is not so much a fundamental intellectual incapacity as a passional attachment to concepts that are congruent with man’s natural individualism. On the one hand, transcending this individualism predisposes man to such an understanding; on the other hand, total metaphysics contributes to this transcending; every spiritual realization has two poles or two points of departure, one being situated in our thought, and the other in our being.

- Form and Substance in the Religions. World Wisdom. 2002. p. 253. ISBN 0-941532-25-9.

Symbolism[edit]

- The language of Sophia perennis is above all symbolism in all its forms, thus the openness to the message of symbols is a gift proper to primordial man and his heirs in every age.

- The Transfiguration of Man. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-94153219-8.

- A symbolism is abstract inasmuch as it signifies a principial reality; it is concrete inasmuch as it communicates the nature of this reality, that is, inasmuch as it renders it present to our experience.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- The language of religion is symbolism, and symbolism is what both separates and unites. It is the symbolism that constitutes the particularity, at once enlightening and separative, characterizing the different religions, and it is symbolism yet again that on the contrary, owing to its universal validity and its illimitation in depth, permits one to reach the religio perennis; to bring out the oneness of the content − and the raison d’être − of the religious phenomenon.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. xii. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

- What is lacking in today's world is a penetrating and comprehensive knowledge of the nature of things; the fundamental truths are always accessible, but they are not obvious for those who refuse to take them into consideration. It goes without saying that it is not a question here of the altogether outward data with which experimental science can provide us, but of realities with which this science does not deal, and cannot deal, and which are transmitted to us by quite different channels, especially those of mythological and metaphysical symbolism, not to mention intellectual intuition, the possibility of which resides principially in every man. The symbolic language of the great traditions of mankind may seem difficult and disconcerting for certain minds, but it is nevertheless intelligible in the light of the orthodox commentaries; symbolism − it must be stressed − is a real and rigorous science, and nothing is more aberrant than to believe that its apparent naivety issues from a crude and "prelogical" mentality. This science, which we may term "sacred," cannot be adapted to the experimental method of the moderns; the domain of revelation, of symbolism, of pure intellection, obviously transcends the physical and psychic planes and is thus situated beyond the domain of methods termed scientific. If we believe that we cannot accept the language of traditional symbolism because it seems to us fantastical and arbitrary, this only shows that we have not yet understood this language and certainly not that we have gone beyond it.

- The Play of Masks. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-94153214-3.

Wisdom[edit]

- Wisdom consists not only in knowing truths and being able to communicate them, but also in the sage’s capacity to recognize the most subtle limitations or hazards of human nature.

- Christianity / Islam. World Wisdom. 2008. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-933316-49-9.

- Wisdom consists not only in becoming detached from the reflections, but also in knowing and feeling that the archetypes are to be found within ourselves and are accessible in the depths of our hearts; we possess what we love to the extent that what we love is worthy of being loved.

- The Transfiguration of Man. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-94153219-8.

- The divine Māyā − Femininity in divinis − is not only that which projects and creates, it is also that which attracts and liberates. The Blessed Virgin as Sedes Sapientiae personifies this merciful Wisdom that descends towards us and that we also bear in our very essence, whether we know it or not; and it is precisely by virtue of this potentiality or virtuality that Wisdom comes down upon us. The immanent seat of Wisdom is the heart of man.

- In the Face of the Absolute. World Wisdom. 2014. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-936597-41-3.

Knowledge[edit]

- Starting from the axiom that all knowledge, by definition, comprises a subject and an object, we shall specify the following: the subject of the knowledge of sensible phenomena is obviously a particular sensorial faculty or the combination of these faculties; the subject of the knowledge of physical principles, or of cosmic categories, is the rational faculty; and the subject of the knowledge of metaphysical principles is the pure intellect and hence intellectual intuition; intuition or intellection and not discursive operation. A knowledge whose subject is not the intellect could not be metaphysical; starting from the observation of phenomena, one cannot reach a reality that only "God in us" can cause us to perceive. Three subjectivities, three modes of certitude: from the relative to the absolute.

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 15-16. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- The principle of knowledge does not of itself imply any limitation; to know is to know all that is knowable, and the knowable coincides with the real, given that a priori and in the Absolute the subject and the object are indistinguishable: to know is to be, and conversely. If we are told that the Absolute is unknowable, this applies, not to our intellective faculty as such, but to a particular de facto modality of this faculty; to a particular husk, not to the substance.

- To Have a Center. World Wisdom. 2015. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-936597-44-4.

- To know God, the Real in itself, the supremely Intelligible, and then to know things in the light of this knowledge, and in consequence also to know ourselves: these are the dimensions of intrinsic and integral intelligence, the only one worthy of the name, strictly speaking, since it alone is properly human.

- Roots of the Human Condition. World Wisdom. 1991. p. 7. ISBN 0-941532-11-9.

- Will for the Good and love of the Beautiful are the necessary concomitants of knowledge of the True, and their repercussions are incalculable.

- The Transcendent Unity of Religions. Quest Books. 1993. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8356-0587-8.

- Only the science of the Absolute gives meaning and discipline to the science of the relative.

- From the Divine to the Human. World Wisdom. 2013. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-936597-32-1.

- It is appropriate to distinguish between a knowledge that is active and mental, namely doctrinal discernment, by which we become conscious of the Truth, and a knowledge that is passive, receptive and cardiac, namely invocatory contemplation, by which we assimilate what we have become aware of.

- Echoes of Perennial Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2012. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-93659700-0.

- The passage from distinctive or mental knowledge to unitive or cardiac knowledge follows from the very content of thought: either we understand imperfectly what the notions of Absolute, Infinite, Essence, Substance, Unity mean, in which case we content ourselves with concepts − and this is what is done by philosophers in the conventional sense of the word; or else we understand these notions perfectly, in which case they oblige us, by virtue of their very content, to transcend conceptual separativity in order to find the Real in the depths of the Heart, not as adventurers, but by availing ourselves of the traditional means without which we can do nothing and are entitled to nothing. Transcendent and exclusive Substance then reveals Itself as immanent and inclusive. It could also be said that since God is All that is, it behooves us to know Him with all that we are; and to know What is infinitely lovable − since but for Him nothing would be lovable − is to love Him infinitely.

- Form and Substance in the Religions. World Wisdom. 2002. p. 49-50. ISBN 0-941532-25-9.

Prayer[edit]

- Every time man stands before God wholeheartedly − that is, "poor" and without being puffed up − he stands on the ground of absolute certitude, the certitude of his conditional salvation and the certitude of God. And that is why God has given us the gift of this supernatural key that is prayer: in order that we might stand before Him as in the primordial state, and as always and everywhere; or as in eternity.

- Survey of Metaphysics and Esoterism. World Wisdom. 2003. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-94153227-3.

- Prayer − in the widest sense − triumphs over the four accidents of our existence: the world, life, the body, the soul; we might also say: space, time, matter, desire. It is situated in existence like a shelter, like an islet. In it alone we are perfectly ourselves, because it puts us into the presence of God. It is like a diamond, which nothing can tarnish and nothing can resist.

- Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts. World Wisdom. 2007. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-933316-42-0.

- The aim of individual prayer is not only to obtain particular favors, but also the purification of the soul: it loosens psychic knots or, in other words, dissolves subconscious coagulations and drains away many secret poisons; it externalizes before God the difficulties, failures and tensions of the soul, which presupposes that the soul be humble and genuine, and this externalization − carried out in the face of the Absolute − has the virtue of reestablishing equilibrium and restoring peace; in a word, of opening us to grace.

- Stations of Wisdom. World Wisdom. 2005. p. 121-122. ISBN 978-0-94153218-1.

- The gift of oneself to God is always the gift of oneself to all; to give oneself to God − though it were hidden from all − is to give oneself to man, for this gift of self has a sacrificial value of an incalculable radiance.

- Light on the Ancient Worlds. World Wisdom. 2006. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-941532-72-3.