John Sartain

John Sartain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 24, 1808 London, England |

| Died | October 25, 1897 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | British, American |

| Signature | |

John Sartain (October 24, 1808 – October 25, 1897) was an English-born American artist who pioneered mezzotint engraving in the United States.[1]

Biography[edit]

John Sartain was born in London, England. He learned line engraving, and produced several of the plates in William Young Ottley's Early Florentine School (1826). In 1828, he began to make mezzotints. He studied painting under John Varley and Henry James Richter.

In 1830, at the age of 22, he emigrated to the United States and settled in Philadelphia. There he studied with Joshua Shaw and Manuel J. de Franca. For about ten years after his arrival in the United States, he painted portraits in oil and miniatures on ivory. During the same time, he found employment in making designs for banknote vignettes, and also in drawing on wood for book illustrations. He was a 33 degree Mason. He pioneered mezzotint engraving in the United States. He engraved plates in 1841–48 for Graham's Magazine, published by George Rex Graham, and believed his work was responsible for the publication's sudden success.[2] Sartain became editor and proprietor of Campbell's Foreign Semi-Monthly Magazine in 1843. He had an interest at the same time in the Eclectic Museum, for which, later, when John H. Agnew was alone in charge, he simply engraved the plates.

-

Pennsylvania Hall burning, 1838. Sartain was an eyewitness.

-

John Sartain, Mary, Queen of Scots, The Evening Before Her Execution

-

John Sartain, Zachary Taylor

Sartain's Magazine[edit]

In 1848, he purchased a half interest in the Union Magazine, a New York-based periodical. He transferred it to Philadelphia, where it was renamed Sartain's Union Magazine, and from 1849 to 1852 he published it with Graham. It became very well known during those four years.

During this time, besides his editorial work and the engravings that had to be made regularly for the periodicals with which he was connected, Sartain produced an enormous quantity of plates for book-illustration.

-

John Sartain

-

John Sartain, Edgar Allan Poe

Sartain was a colleague and friend of Edgar Allan Poe. Around July 2, 1849, about four months before Poe's death, the author unexpectedly visited Sartain's house in Philadelphia. Looking "pale and haggard" with "a wild and frightened expression in his eyes", Poe told Sartain that he was being pursued and needed protection;[3] Poe asked for a razor so that he could shave off his mustache to become less recognizable. Sartain offered to cut it off himself using scissors.[4] Poe had said he had overheard people while on the train who were conspiring to murder him. Sartain asked why anyone would want to kill him, Poe answered it was "a woman trouble". However, later when Sartain let Poe stay the night with him at his house, Poe informed him that he may have been hallucinating. This incident was four months before Poe's death.[3] Poe gave Sartain a new poem, The Bells, which was published in Sartain's Union Magazine in November 1849, a month after Poe's death.[5] Sartain's also published the first authorized printing of Annabel Lee, also posthumously.[6]

Years in Philadelphia[edit]

After his arrival in Philadelphia, Sartain took an active interest in art matters there. He held various offices in the Artists' Fund Society, the School of Design for Women, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and was actively connected with other educational institutions in the city. He had visited Europe several times, and on the occasion of his second visit in 1862 he was elected a member of the society "Artis et Amicitiæ" in Amsterdam.[7]

Sartain had charge of the art department of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, in 1876. In recognition of his services there, the king of Italy conferred on him the title of cavaliere of the Order of the Crown of Italy. His architectural knowledge was frequently requisitioned: he took a prominent part in the work of the committee on the Washington Memorial by Rudolf Siemering in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, and he designed medallions for the monument to George Washington and Lafayette erected in 1869 in Monument Cemetery, Philadelphia.[7] His Reminiscences of a Very Old Man (New York, 1899) are of unusual interest.[1]

-

John Sartain, William Henry Harrison

-

John Sartain, Alexander Pope

-

John Sartain, Cinque (The Amistad Case)

Sartain was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1897.[8] Upon his death later that year, the 89-year-old Sartain was buried in Monument Cemetery.[9] Shortly before his death, The Philadelphia School of Design for Women created the John Sartain Fellowship in recognition of his 28 year tenure as Director.[10]

In 1956 the cemetery was condemned by the city and given to Temple University which cleared it for a parking lot. Sartain's body was not claimed and he and approximately 20,000 other unclaimed bodies were re-interred in a large mass grave at Lawnview Cemetery.[11] The tombstones, including the cemetery's 70 feet high central monument to George Washington and General Lafayette and his family monument (all designed by Sartain) were dumped into the Delaware River to serve as the foundations for the Betsy Ross Bridge.[12]

Family[edit]

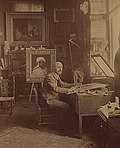

John Sartain married Susannah Longmate Swaine[13] and they had eight children.[14] Samuel (1830-1906), who was an engraver; Henry (1833-1895); William (1843-1925); and Emily Sartain pursued careers as artists.[15][16] Emily Sartain first practised art as an engraver under her father.[14] She studied at the Pennsylvania Academy under Christian Schussele,[17][18] and then, until 1875, with Évariste Vital Luminais in Paris.[13] In 1886, she became principal of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women.[19] William Sartain engraved under his father's supervision until he was about 24. From 1867 to 1868, he studied under Christian Schussele and at the Pennsylvania Academy. He then went to Paris, where he studied with Léon Bonnat. In 1877, he returned to the United States, settling in New York, where he was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1880. He was one of the founders of the Society of American Artists. He painted both landscape and figure subjects.[20]

-

Emily Sartain, 1876 plate

-

William Sartain in his studio, circa 1900

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998: 330. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9.

- ^ a b Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991: 416. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 246. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books, 2001: 25. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. New York: Cooper Square Press, 1992: 244. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ^ a b Wilson & Fiske 1889.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2024-02-21.

- ^ Abstract of Proceedings of the Supreme Council of Sovreign Grand Inspectors-General of the Thirty-Third and Last Degree Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite. Binghamton, NY: Binghamton Republican Printers. 1898. p. 137. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "An experiment in training for the useful and the beautiful ; Training for the useful and the beautiful ; a history". Women Working, 1800-1930 - CURIOSity Digital Collections. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ Campbell, Tad D. "Charles M. Appleton Biography". www.suvpac.org. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Stone Angels, 6 May 2011, "How Monument Cemetery Was Destroyed". Accessed 25 July 2011.

- ^ a b Dowd, M. Jane (1978). Ohles, John F. (ed.). Biographical Dictionary of American Educators. Vol. 3. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 1148–1149 – via Q.[dead link]

- ^ a b Martinez, Katharine; Talbott, Page; Johns, Elizabeth (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- ^ "The Sartain family: PAFA's most famous artistic dynasty". Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ Morgan, Ann Lee (Former Visiting Assistant Professor University of Illinois at Chicago) (27 June 2007). The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists. Oxford University Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-19-802955-7.

- ^ Clement, Russell T.; Houzé, Annick; Erbolato-Ramsey, Christiane (2000). "The Women Impressionists: A Sourcebook". Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 32.[dead link]

- ^ Ricci, Patricia Likos (2000). "Bella, Cara Emilia: The Italianate Romance of Emily Sartain and Thomas Eakins". In Martinez, Katherine; Talbott, Page (eds.). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 120–137. ISBN 978-1566397919.

- ^ Hoffmann, Mott; Sharon, Amanda (2008). Moore College of Art & Design. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5659-8.

- ^ Wilson & Fiske 1900.

References[edit]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sartain, John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton., Wilson and Fiske

External links[edit]

- Sartain Images Archived 2018-11-24 at the Wayback Machine Link to some John Sartain engravings at Old Book Art.

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on John Sartain.

- Sartain's Union Magazine at Google Book Search

- John Sartain's The reminiscences of a very old man, 1808–1897, publ. 1899, D. Appleton, NY

- "Sartain family papers, 1795–1944", Archives of American Art

- Poe: Influences Friends – John Sartain