Edwin H. Land

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

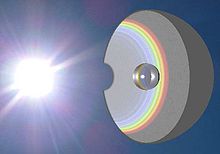

Edwin Herbert Land (May 7, 1909 – March 1, 1991) was an American scientist and inventor. Among other things, he invented inexpensive filters for polarizing light, a practical system of in-camera instant photography, and his retinex theory of color vision.

Quotes[edit]

- We live in a world changing so rapidly that what we mean frequently by common sense is doing the thing that would have been right last year.

- Statement to Polaroid Corporation employes (25 June 1958), as quoted in Insisting on the Impossible : The Life of Edwin Land (1998) by Victor K. McElheny, p. 189

- Now, partly that was work, and partly that was brains, but very largely it was having the guts, the guts to be immodest in the right way.

- On the growth of Polaroid, in a statement to employees (25 June 1958), as quoted in Insisting on the Impossible : The Life of Edwin Land (1998) by Victor K. McElheny, p. 198

- One of the best ways to keep a great secret is to shout it.

- Address to Polaroid employees at Symphony Hall in Boston, Massachusetts (5 February 1960), as quoted in Insisting on the Impossible : The Life of Edwin Land (1998) by Victor K. McElheny, p. 7

- Land was not the first to make such observations; in One Man in His Time (1922), p. 162, Ellen Glasgow has a character state:

- Half the time when he is telling the truth, it sounds like a joke, and that keeps people from believing him. He says the best way to keep a secret is to shout it from the housetops; and I've heard him say things straight out that sounded so far fetched nobody would think he was in earnest. I was the only person who knew that he was speaking the truth.

- In a few wretched buildings, we created a whole new industry with international significance.

- Address to Polaroid employees at Symphony Hall in Boston, Massachusetts (5 February 1960), as quoted in Insisting on the Impossible : The Life of Edwin Land (1998) by Victor K. McElheny, p. 198

- It was not a question of the ineptitude that might be revealed by the truth, or the possible damage that the whole program of negotiation for peace may have suffered … and it was not a question of whether with foresight that particular crisis could have been avoided. The issue was this: Does an American, when he represents all Americans, have to tell the truth at any cost? The answer is yes, and the consequence of the answer is that our techniques for influencing the rest of the world cannot be rich and flexible like the techniques of our competitors. We can be dramatic, even theatrical; we can be persuasive; but the message we are telling must be true.

- On the lessons of the U-2 crisis, in an address in 1960, quoted in "Edwin H. Land : Science, And Public Policy" (9 November 1991) by Richard L. Garwin

- The world is a scene changing so rapidly that it takes every bit of intuitive ability you have, every brain cell each one of you has, to make the sensible decision about what to do next. You cannot rely upon what you have been taught. All you have learned from history is old ways of making mistakes. There is nothing that history can tell you about what we must do tomorrow. Only what we must not do.

- Address to Polaroid employees at Symphony Hall in Boston, Massachusetts (5 February 1960), as quoted in Insisting on the Impossible : The Life of Edwin Land (1998) by Victor K. McElheny, p. 198

- Our society is changing so rapidly that none of us can know what it is or where it is going. All of us who are mature feel that there are historic principles of behavior and morality, of things that we all believe in that are being lost, not because young people couldn't believe in them, but because there is no language for translating them into contemporary terms.

The search for that language, the search for the ways to tell young people what we know as we grow older — the permanent and wonderful things about life — will be one of the great functions of this system. We are losing this generation. We all know that. We need a way to get them back.- Testimony in The Public Television Act of 1967 : Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Communications, by the United States Congress, p. 167

- An essential aspect of creativity is not being afraid to fail. Scientists made a great invention by calling their activities hypotheses and experiments. They made it permissible to fail repeatedly until in the end they got the results they wanted. In politics or government, if you made a hypothesis and it didn't work out, you had your head cut off.

- As quoted in "A Genius and His Magic Camera" in LIFE magazine (27 October 1972); also in The Instant Image : Edwin Land and the Polaroid Experience (1978) by Mark Olshaker, p. 65

- My whole life has been spent trying to teach people that intense concentration for hour after hour can bring out in people resources they didn't know they had.

- "A Talk with Polaroid's Dr. Edwin Land" in Forbes Vol. 115, No. 7 (1 April 1975), p. 49

- Over the years, I have learned that every significant invention has several characteristics. By definition it must be startling, unexpected, and must come into a world that is not prepared for it. If the world were prepared for it, it would not be much of an invention.

- "A Talk with Polaroid's Dr. Edwin Land" in Forbes Vol. 115, No. 7 (1 April 1975), p. 50

- There's a rule they don't teach you at the Harvard Business School. It is, if anything is worth doing, it's worth doing to excess.

- Comment after a 1977 Polaroid shareholder's meeting, as quoted in The Icarus Paradox : How Exceptional Companies Bring About Their Own Downfall; New Lessons in the Dynamics of Corporate Success, Decline, and Renewal (1990) by Danny Miller, p. 126

- Ordinarily when we talk about the human as the advanced product of evolution and the mind as being the most advanced product of evolution, there is an implication that we are advanced out of and away from the structure of the exterior world in which we have evolved, as if a separate product had been packaged, wrapped up, and delivered from a production line. The view I am presenting proposes a mechanism more and more interlocked with the totality of the exterior. This mechanism has no separate existence at all, being in a thousand ways united with and continuously interacting with the whole exterior domain. In fact there is no exterior red object with a tremendous mind linked to it by only a ray of light. The red object is a composite product of matter and mechanism evolved in permanent association with a most elaborate interlock. There is no tremor in what we call the "outside world" that is not locked by a thousand chains and gossamers to inner structures that vibrate and move with it and are a part of it.

The reason for the painfulness of all philosophy is that in the past, in its necessary ignorance of the unbelievable domains of partnership that have evolved in the relationship between ourselves and the world around us, it dealt with what indeed have been a tragic separation and isolation. Of what meaning is the world without mind? The question cannot exist.- Address to the Society of Photographic Scientists and Engineers, Los Angeles, California (5 May 1977), published Harvard Magazine (January-February 1978), pp. 23–26

- My motto is very personal and may not fit anyone else or any other company. It is: Don't do anything that someone else can do. Don't undertake a project unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible.

- As quoted in "The Vindication of Edwin Land" in Forbes magazine, Vol. 139 (4 May 1987) p. 83; this was later humorously altered:

- Don't do anything that someone else can do. Don't undertake a project unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible.

- Edwin Ladd, Department of Astronomy, Harvard University (August, 1990), as quoted by Lincoln J. Greenhill at Harvard University

- Don't do anything that someone else can do. Don't undertake a project unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible.

- We have not found anti-intellectualism a problem at the Polaroid Corporation, except in the very initial state of penetration. It only takes a day to change someone from an anti-intellectual to an intellectual by persuading him that he might be one!

- Speaking at Columbia University, as quoted in The Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, Vol. 37, No. 3 (1992), p. 537

- There's a tremendous popular fallacy which holds that significant research can be carried out by trying things. Actually it is easy to show that in general no significant problem can be solved empirically, except for accidents so rare as to be statistically unimportant. One of my jests is to say that we work empirically — we use bull's eye empiricism. We try everything, but we try the right thing first!

- As quoted in The Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, Vol. 37, No. 3 (1992), p. 537

- You always start with a fantasy. Part of the fantasy technique is to visualize something as perfect. Then with the experiments you work back from the fantasy to reality, hacking away at the components.

- As quoted in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 146, no. 1, (March 2002), p. 115

- If you sense a deep human need, then you go back to all the basic science. If there is some missing, then you try to do more basic science and applied science until you get it. So you make the system to fulfill that need, rather than starting the other way around, where you have something and wonder what to do with it.

- As quoted in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 146, no. 1, (March 2002), p. 115

Research by the Business Itself (1945)[edit]

- "Research by the Business Itself" in The Future of Industrial Research : Papers and Discussion (1945) edited by Thomas Midgley

- I believe quite simply that the small company of the future will be as much a research organization as it is a manufacturing company, and that this new company is the frontier for the next generation.

- I believe it is pretty well established now that neither the intuition of the sales manager nor even the first reaction of the public is a reliable measure of the value of a product to the consumer. Very often the best way to find out whether something is worth making is to make it, distribute it, and then to see, after the product has been around a few years, whether it was worth the trouble.

- Who can object to a monopoly when there are several thousands of them? Who can object to a monopoly when every few years the company enjoying the monopoly revises, alters, perhaps even discards its product, in order to supply a superior one to the public? Who can object to a monopoly when any new company, if it is built around a scientific nucleus, can create a new monopoly of its own by creating a wholly new field?

Congressional testimony (1945)[edit]

- Statement to the US Senate Military Affairs Committee at the Joint Hearings on Science Bills (October 1945)

- Most large industrial concerns are limited by policy to special directions of expansion within the well-established field of the company. On the other hand, most small companies do not have the resources or the facilities to support "scientific prospecting." Thus the young man leaving the university with a proposal for a new kind of activity is frequently not able to find a matrix for the development of his ideas in any established industrial organization.

- As I visualize it, the business of the future will be a scientific, social and economic unit. It will be vigorously creative in pure science where its contributions will compare with those of the universities... the machinist will be proud of and informed about the company's scientific advances; the scientist will enjoy the reduction to practice of his basic perceptions. … year by year our national scene would change in the way, I think, all Americans dream of. Each individual will be a member of a group small enough so that he feels a full participant in the purpose and activity of the group. His voice will be heard and his individuality recognized.

Generation of Greatness (1957)[edit]

- What do I mean by the Generation of Greatness?

I mean that in this age, in this country, there is an opportunity for the development of man's intellectual, cultural, and spiritual potentialities that has never existed before in the history of our species. I mean not simply an opportunity for greatness for a few, but an opportunity for greatness for the many.

- I believe that each young person is different from any other who has ever lived, as different as his fingerprints: that he could bring to the world a wonderful and special way of solving unsolved problems, that in his special way, he can be great. Now don't misunderstand me. I recognize that this merely great person, as distinguished from the genius, will not be able to bridge from field to field. He will not have the ideas that shorten the solution of problems by hundreds of years. He will not suddenly say that mass is energy, that is genius. But within his own field he will make things grow and flourish; he will grow happy helping other people in his field, and to that field he will add things that would not have been added, had he not come along.

- I believe there are two opposing theories of history, and you have to make your choice. Either you believe that this kind of individual greatness does exist and can be nurtured and developed, that such great individuals can be part of a cooperative community while they continue to be their happy, flourishing, contributing selves — or else you believe that there is some mystical, cyclical, overriding, predetermined, cultural law — a historic determinism.

The great contribution of science is to say that this second theory is nonsense. The great contribution of science is to demonstrate that a person can regard the world as chaos, but can find in himself a method of perceiving, within that chaos, small arrangements of order, that out of himself, and out of the order that previous scientists have generated, he can make things that are exciting and thrilling to make, that are deeply spiritual contributions to himself and to his friends. The scientist comes to the world and says, "I do not understand the divine source, but I know, in a way that I don't understand, that out of chaos I can make order, out of loneliness I can make friendship, out of ugliness I can make beauty."

I believe that men are born this way — that all men are born this way. I know that each of the undergraduates with whom I talked shares this belief. Each of these men felt secretly — it was his very special secret and his deepest secret — that he could be great.

But not many undergraduates come through our present educational system retaining this hope. Our young people, for the most part — unless they are geniuses — after a very short time in college give up any hope of being individually great. They plan, instead, to be good. They plan to be effective, They plan to do their job. They plan to take their healthy place in the community. We might say that today it takes a genius to come out great, and a great man, a merely great man, cannot survive. It has become our habit, therefore, to think that the age of greatness has passed, that the age of the great man is gone, that this is the day of group research, that this is the day of community progress. Yet the very essence of democracy is the absolute faith that while people must cooperate, the first function of democracy, its peculiar gift, is to develop each individual into everything that he might be. But I submit to you that when in each man the dream of personal greatness dies, democracy loses the real source of its future strength.

- The fact that civilization is becoming more intricate must not mean that we treat men for a longer period as immature. Does it not mean, perhaps, the opposite: that we must skillfully make them mature sooner, that we must find ways of handling the intricacy of our culture?

- Now this error in attitude — mistaking these men for boys — permeates the whole scholastic domain, permeates it so thoroughly that it is hard for anyone within the domain to recognize it.

What do I mean by saying that a man is treated as a boy? I mean that he is told, the moment he arrives, that his secret dream of greatness is a pipe-dream; that it will be a long time before he makes a significant, personal contribution — if ever.

He is told this not with words. He is told this in a much more convincing way. He is shown, in everything that happens to him, that nobody could dream that he could make a significant, personal contribution.

- The role of science is to be systematic, to be accurate, to be orderly, but it certainly is not to imply that the aggregated, successful hypotheses of the past have the kind of truth that goes into a number system.

- I would urge that just as democracy initially meant the right of man to defend himself, to have a sword, and then meant the right to write, and then meant the right to read — so, now, democracy means the right to have the scientific experience.

- A contemporary man who has not participated intimately in actual work in science is, in my opinion, not a modern man. I believe that this experience in science should come early in the life of all of our pupils.

- There are areas where untrained people may work effectively and with limited equipment. Our pupil doesn't need a big laboratory to do this, he needs freedom; he needs encouragement.

- I think we must say this to each department: "Sharpen up the edges of ideas for the students in fields other than your own. They will not have years in which to find out what you meant, years during which they might achieve a sense of rich insight into your domain. But they are intelligent, they are earnest in their own department; they will profit all their lives from one year of brilliant teaching."

- In thinking about what the human animal might have gone through in the evolutionary process, have you wondered how some of the small changes which must have occurred could have had survival value? Haven't you wondered how they could have survived, when, in all of our experimental work every small change we make dies? … How many changes must have occurred in the human eye, occurred and died, before one change came along — an apparently trivial change … that gave the whole animal a significant increase in its power to perceive and hunt down its enemies and find its food. This is the kind of change that survives.

- In my opinion, neither organisms nor organizations evolve slowly and surely into something better, but drift until some small change occurs which has immediate and overwhelming significance. The special role of the human being is not to wait for these favorable accidents but deliberately to introduce the small change that will have great significance.

To treat young men like men; to use modern recording techniques to capture the moment of exciting teaching; to gather ninety great men out of our one-hundred and seventy million — these, in retrospect, will seem like small changes indeed if they succeed in building a generation of greatness.

Quotes about Land[edit]

- Edwin Land worked passionately to realize his vision for the betterment of society. … His vision of science for the public was a great one, and highly original. … Although Edwin Land must have realized that much about him was unique, he tried to identify those elements of his own being and experience that could be replicated to the benefit of his nation and the world. … As Ken Olsen observed in his talk this morning about Land and Polaroid, knowing where you want to go is a big advantage.

- I always thought of myself as a humanities person as a kid, but I liked electronics. Then I read something that one of my heroes, Edwin Land of Polaroid, said about the importance of people who could stand at the intersection of humanities and sciences, and I decided that's what I wanted to do.

- Steve Jobs as quoted in: Isaacson, Walter (2013). Steve Jobs. Simon and Schuster. p. xix. (1st edition 2011)

- Land was legendary for his eccentric and exhausting work habits, which dated back to his Harvard days. Like the proverbial mad scientist, when Land was immersed in a project, he would lock himself in the lab for days on end, stopping only long enough to eat and often not bothering to change clothes.

When he was on one of these jags, Land's assistants would be scheduled in shifts to keep up with him since they had a tendency to fold at the knees without sleep.

- Besides energy, the dominant impressions Land created were artistic sensibility, a sense of drama, delight in experiment, relentless optimism. Less evident was a remarkable ability to keep both work and people in compartments. Less than six feet tall, Land had intense eyes and a shock of black hair that riveted attention on him. Despite a soft voice and frequent use of half-sentences, Land was able to convert interior monologues into dramatic public presentations. The watchword was: "If anything is worth doing, it's worth doing to excess."

- Victor K. McElheny, in "Edwin Herbert Land" in Biographical Memoirs, Vol. 77 (1999) by the National Academy of Sciences

- Din never had an ordinary reaction to anything!

- Jerome Wiesner, as quoted in "Edwin Herbert Land" by Victor K. McElheny, in Biographical Memoirs Vol. 77 (1999) by the National Academy of Sciences ("Din" was a nickname Land acquired in childhood.)