Robert A. Heinlein

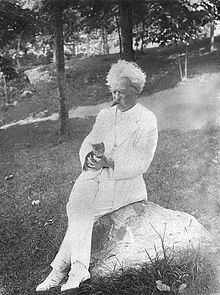

Appearance

(Redirected from Heinlein)

Robert Anson Heinlein (7 July 1907 – 8 May 1988) was one of the most popular, influential, and controversial authors of science fiction of the 20th Century.

See also pages for the novels:

- Starship Troopers (1959)

- Stranger in a Strange Land (1961)

- Glory Road (1963)

- The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966)

- Time Enough for Love (1973)

- Job: A Comedy of Justice (1984)

Quotes

[edit]

- I think that science fiction, even the corniest of it, even the most outlandish of it, no matter how badly it's written, has a distinct therapeutic value because all of it has as its primary postulate that the world does change. I cannot overemphasize the importance of that idea.

- "The Discovery of the Future," Guest of Honor Speech, 3rd World Science Fiction Convention, Denver, Colorado (4 July 1941)

- How anybody expects a man to stay in business with every two-bit wowser in the country claiming a veto over what we can say and can't say and what we can show and what we can't show — it's enough to make you throw up. The whole principle is wrong; it's like demanding that grown men live on skim milk because the baby can't eat steak.

- On censorship, in The Man Who Sold the Moon (1950), p. 188; this may be the origin of a remark which in recent years has sometimes become misattributed to Mark Twain: Censorship is telling a man he can't have a steak just because a baby can't chew it.

- Never worry about theory as long as the machinery does what it's supposed to do.

- Waldo & Magic, Inc. (1950)

- The Koran cannot be translated — the "map" changes on translation no matter how carefully one tries.

- Robert A. Heinlein, in Stranger in a Strange Land (1961)

- The answer to any question starting, "Why don't they—" is almost always, "Money".

- Shooting Destination Moon (1950)

- Take sex away from people. Make it forbidden, evil. Limit it to ritualistic breeding. Force it to back up into suppressed sadism. Then hand the people a scapegoat to hate. Let them kill a scapegoat occasionally for cathartic release. The mechanism is ages old. Tyrants used it centuries before the word "psychology" was ever invented. It works, too.

- Revolt in 2100 (1953)

- The capacity of the human mind for swallowing nonsense and spewing it forth in violent and repressive action has never yet been plumbed.

- Revolt in 2100 (1953), postscript

- The death rate is the same for us as for anybody ... one person, one death, sooner or later.

- Tunnel in the Sky (1955), Captain Helen Walker, Ch. 2

- I also think there are prices too high to pay to save the United States. Conscription is one of them. Conscription is slavery, and I don't think that any people or nation has a right to save itself at the price of slavery for anyone, no matter what name it is called. We have had the draft for twenty years now; I think this is shameful. If a country can't save itself through the volunteer service of its own free people, then I say : Let the damned thing go down the drain!

- Guest of Honor Speech at the 29th World Science Fiction Convention, Seattle, Washington (1961)

- The difference between science and the fuzzy subjects is that science requires reasoning, while those other subjects merely require scholarship.

- In: Time Enough for Love: the lives of Lazarus Long; a novel , (1973), p. 366

- At the time I wrote Methuselah’s Children I was still politically quite naive and still had hopes that various libertarian notions could be put over by political processes… It [now] seems to me that every time we manage to establish one freedom, they take another one away. Maybe two. And that seems to me characteristic of a society as it gets older, and more crowded, and higher taxes, and more laws. I would say that my position is not too far from that of Ayn Rand's; that I would like to see government reduced to no more than internal police and courts, external armed forces — with the other matters handled otherwise. I'm sick of the way government sticks its nose in everything, now.

- The Robert Heinlein Interview, and other Heinleiniana (1973) by J. Neil Schulman (published in 1990)

- I would say that my position is not too far from that of Ayn Rand's; that I would like to see government reduced to no more than internal police and courts, external armed forces — with the other matters handled otherwise. I'm sick of the way the government sticks its nose into everything, now.

- The Robert Heinlein Interview (1973)

- I think that describes me, too — still a democrat not because I love the Common People and not because I think democracy is so successful (look around you) but, because in a lifetime of thinking about it and learning all that I could, I haven't found any other political organization that worked as well.

As for libertarian, I've been one all my life, a radical one. You might use the term "philosophical anarchist" or "autarchist" about me, but "libertarian" is easier to define and fits well enough.- 1975 Statement to Judith Merrill, who had called herself a democrat and a libertarian, stating that such terms described him as well, as quoted in Robert A. Heinlein : In Dialogue with His Century, Volume 2: The Man Who Learned Better | 1948-1988 (2014), p. 389

- I started clipping and filing by categories on trends as early as 1930 and my "youngest" file was started in 1945.

Span of time is important; the 3-legged stool of understanding is held up by history, languages, and mathematics. Equipped with these three you can learn anything you want to learn. But if you lack any one of them you are just another ignorant peasant with dung on your boots.- "The Happy Days Ahead" in Expanded Universe (1980)

- Each generation thinks it invented sex; each generation is totally mistaken. Anything along that line today was commonplace both in Pompeii and in Victorian England; the differences lie only in the degree of coverup — if any.

- Introduction to "Cliff and the Calories," in Expanded Universe, (1980), pg. 355

- My wife Ticky is an anarchist-individualist ... When she was in the Navy during the early 'forties she showed up one morning in proper uniform but with her red hair held down by a simple navy-blue band — a hair ribbon. It was neat (Ticky is always neat) and it suited the rest of her outfit esthetically, but it was undeniably a hair ribbon and her division officer had fits.

"If you can show me," Ticky answered with simple dignity, "where it says one word in the Navy Uniform Regulations on the subject of hair ribbons, I'll take it off. Otherwise not."

See what I mean? She doesn't have the right attitude.- Tramp Royale (1992)

Short fiction

[edit]The Past Through Tomorrow (1967)

[edit]- Page numbers from the hardcover first edition, published by G. P. Putnam's Sons

- See Robert A. Heinlein's Internet Science Fiction Database page for original publication details

- All ellipses and italics as in the book

- How can I possibly put a new idea into your heads, if I do not first remove your delusions?

- Life-Line (p. 15)

- He seeks order, not truth. Suppose truth defies order, will he accept it? Will you? I think not.

- Life-Line (p. 16)

- There are but two ways of forming an opinion in science. One is the scientific method; the other, the scholastic. One can judge from experiment, or one can blindly accept authority. To the scientific mind, experimental proof is all important and theory is merely a convenience in description, to be junked when it no longer fits. To the academic mind, authority is everything and facts are junked when they do not fit theory laid down by authority.

- Life-Line (p. 24)

- There has grown up in the minds of certain groups in this country the notion that because a man or corporation has made a profit out of the public for a number of years, the government and the courts are charged with the duty of guaranteeing such profit in the future, even in the face of changing circumstances and contrary public interest. This strange doctrine is not supported by statute nor common law. Neither individuals nor corporations have any right to come into court and ask that the clock of history be stopped, or turned back, for their private benefit.

- Life-Line (p. 25)

- There is nothing in this world so permanent as a temporary emergency.

- The Man Who Sold the Moon (p. 100)

- He decided to stay in his space suit; explosive decompression didn’t appeal to him. Come to think about it, death from old age was his choice.

- The Long Watch (p. 214)

- High I.Q., good compatibility index, superior education—everything that makes a person pleasant and easy and interesting to have around.

- The Long Watch (p. 255)

- History is never surprising—after it happens.

- Logic of Empire (p. 333)

- You have attributed conditions to villainy that simply result from stupidity.

- Logic of Empire (p. 335); this is one of the earliest known variants of an idea which has become known as Hanlon's razor.

- Don’t pay any attention to what she says. Half of it’s always wrong and she doesn’t mean the rest.

- The Menace from Earth (p. 351)

- I think perhaps of all the things a police state can do to its citizens, distorting history is possibly the most pernicious.

- If This Goes On— (p. 401)

- I began to sense faintly that secrecy is the keystone of all tyranny. Not force, but secrecy...censorship. When any government, or any church for that matter, undertakes to say to its subjects, “This you may not read, this you must not see, this you are forbidden to know,” the end result is tyranny and oppression, no matter how holy the motives. Mighty little force is needed to control a man whose mind has been hoodwinked; contrariwise, no amount of force can control a free man, a man whose mind is free. No, not the rack, not fission bombs, not anything—you can’t conquer a free man; the most you can do is kill him.

- If This Goes On— (p. 401)

- I was too busy to oblige them by dying just now.

- If This Goes On— (p. 412)

- Just now I’m writing a series of oh-so-respectful articles about the private life of the Prophet and his acolytes and attending priests, how many servants they have, how much it costs to run the Palace, all about the fancy ceremonies and rituals, and such junk. All of it perfectly true, of course, and told with unctuous approval. But I lay it on a shade too thick. The emphasis is on the jewels and the solid gold trappings and how much it all costs, and I keep telling the yokels what a privilege it is for them to be permitted to pay for such frippery and how flattered they should feel that God’s representative on earth lets them take care of him.

- If This Goes On— (p. 426)

- “Do you seriously expect to start a rebellion with picayune stuff like that?”

“It’s not picayune stuff, because it acts directly on their emotions, below the logical level. You can sway a thousand men by appealing to their prejudices quicker than you can convince one man by logic. It doesn’t have to be a prejudice about an important matter either.- If This Goes On— (p. 426)

- From my point of view, a great deal of openly expressed piety is insufferable conceit.

- If This Goes On— (p. 431)

- “Johnnie, the nice thing about citing God as an authority is that you can prove anything you set out to prove. It’s just a matter of selecting the proper postulates, then insisting that your postulates are ‘inspired.’ Then no one can possibly prove that you are wrong.”

- If This Goes On— (p. 432)

- First they junked the concept of “justice.” Examined semantically “justice” has no referent—there is no observable phenomenon in the space-time-matter continuum to which one can point, and say, “This is justice.” Science can deal only with that which can be observed and measured. Justice is not such a matter; therefore it can never have the same meaning to one as to another; any “noises” said about it will only add to confusion.

But damage, physical or economic, can be pointed to and measured. Citizens were forbidden by the Covenant to damage another. Any act not leading to damage, physical or economic, to some particular person, they declared to be lawful.- Coventry (pp. 500-501)

- Mass psychology is not simply a summation of individual psychologies; that is a prime theorem of social psychodynamics—not just my opinion; no exception has ever been found to this theorem. It is the social mass-action rule, the mob-hysteria law, known and used by military, political, and religious leaders, by advertising men and prophets and propagandists, by rabble rousers and actors and gang leaders, for generations before it was formulated in mathematical symbols. It works.

- Methuselah’s Children (p. 535)

- “What course of action do you favor?”

“Me? Why, none. Mary, if there is any one thing I have learned in the past couple of centuries, it’s this: These things pass. Wars and depressions and Prophets and Covenants—they pass. The trick is to stay alive through them.”- Methuselah’s Children (p. 539)

- “The truth of a proposition has little or nothing to do with its psychodynamics. The notion that ‘truth will prevail’ is merely a pious wish; history doesn’t show it.”

- Methuselah’s Children (p. 606)

- “Yes, maybe it’s just one colossal big joke with no point to it.” Lazarus stood up and stretched and scratched his ribs. “But I can tell you this, Andy, whatever the answers are, here’s one monkey that’s going to keep on climbing, and looking around him to see what he can see, as long as the tree holds out.”

- Methuselah’s Children (p. 667; closing words)

- Page numbers from the trade paperback edition, published by Tor, ISBN 0-312-87557-6

- See Robert A. Heinlein's Internet Science Fiction Database page for original publication details

- All dashes as in the book

- I don’t believe he would have conceded that he had five fingers on his right hand without an auditor to back him up.

- Magic, Inc. (p. 20)

- “We must make the fee contingent on results.”

“Did you ever hear of anyone in his right mind dealing with a wizard on any other basis?”- Magic, Inc. (p. 21)

- We white men in this country are inclined to underestimate the black man—I know I do—because we see him out of his cultural matrix. Those we know have had their own culture wrenched from them some generations back and a servile pseudo culture imposed on them by force. We forget that the black man has a culture of his own, older than ours and more solidly grounded, based on character and the power of the mind rather than the cheap, ephemeral tricks of mechanical gadgets. But it is a stern, fierce culture with no sentimental concern for the weak and the unfit, and it never quite dies out.

- Magic, Inc. (p. 49)

- He couldn’t be wrong, basically, yet the doctor had certainly pointed out logical holes in his position. From a logical standpoint the whole world might be a fraud perpetrated on everybody. But logic meant nothing—logic itself was a fraud, starting with unproved assumptions incapable of proving anything. The world is what it is!—And carries its own evidence of trickery.

But does it? What did he have to go on? Could he lay down the line between known facts and everything else and then make a reasonable interpretation of the world, based on facts alone—an interpretation free from complexities of logic and no hidden assumptions of points not certain. Very well—

First fact, himself. He knew himself directly. He existed.

Second facts, the evidence of his “five senses,” everything that he himself saw and heard and smelled and tasted with his physical senses. Subject to their limitations, he must believe his senses. Without them he was entirely solitary, shut up in a locker of bone, blind, deaf, cut off, the only being in the world.

And that was not the case. He knew that he did not invent the information brought to him by his senses. There had to be something else out there, some otherness that produced the things his senses recorded. All philosophies that claimed that the physical world around him did not exist except in his imagination were sheer nonsense.

But beyond that, what? Were there any third facts on which he could rely? No, not at this point. He could not afford to believe anything that he was told, or that he read, or that was implicitly assumed to be true about the world around him. No, he could not believe any of it, for the sum total of what he had been told and read and been taught in school was so contradictory, so senseless, so wildly insane that none of it could be believed unless he personally confirmed it.

Wait a minute—The very telling of these lies, these senseless contradictions, was a fact in itself, known to him directly. To that extent they were data, probably very important data.

The world as it had been shown to him was a piece of unreason, an idiot’s dream. Yet it was on too mammoth a scale to be without some reason. He came wearily back to his original point: Since the world could not be as crazy as it appeared to be it must necessarily have been arranged to appear crazy in order to deceive him as to the truth.

Why have they done it to him? And what was the truth behind the sham? There must be some clue in the deception itself. What thread ran through it all? Well, in the first place he had been given a superabundance of explanations of the world around him, philosophies, religions, “common sense” explanations. Most of them were so clumsy, so obviously inadequate, or meaningless, that they could hardly have expected him to take them seriously. They must have intended them simply as misdirection.- They— (pp. 115-116)

- It is true that most religions which have been offered me teach in mortality, but no the fashion in which they teach it. The surest way to lie convincingly is to tell the truth unconvincingly. They did not wish me to believe.

- They— (p. 118)

- It may possibly be urged the shape of a culture—its mores, evaluations, family organizations, eating habits, living patterns, pedagogical methods, institutions, forms of government, and so forth—arise from the economic necessities of its technology.

- Waldo (p. 134)

- It was fairly evident that at least 90 per cent of all magic, probably more, was balderdash and sheer mystification.

- Waldo (p. 186)

- Stop fidgeting, Mr. Randall! I know this is difficult for your little mind, but for once you really must think about something longer than your nose and wider than your mouth believe me!

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (p. 242)

- Why stay in Chicago; what did the town have to justify its existence? One decent boulevard, one decent suburb to the north, priced for the rich, two universities and a lake. As for the rest, endless miles of depressing, dirty streets. The town was one big stockyard.

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (p. 261)

- I sometimes think that my own weakness lies in not realizing the full depths of the weakness and stupidity of men. As a reasonable creature myself I seem to have an unfortunate tendency to expect others unlike myself to be reasonable.

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (p. 267)

- “Once there was a race, quite unlike the human race—quite. I have no way of describing to you what they looked like or how they lived, but they had one characteristic you can understand: they were creative. The creating and enjoying of works of art was their occupation and their reason for being. I say ‘art’ advisedly, for art is undefined, undefinable, and without limits. I can use the word without fear of misusing it, for it has no exact meaning. There are as many meanings as there are artists.”

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (p. 303)

- “But this is crazy, Pete. They must be absolute, complete and teetotal nuts.”

“Any law says a cop has to be sane to be on the force?”- Our Fair City (p. 322)

Off the Main Sequence (2005)

[edit]- Page numbers from the hardcover first edition, published by The Science Fiction Book Club, ISBN 1-58288-184-7

- See Robert A. Heinlein's Internet Science Fiction Database page for original publication details

- All ellipses and italics as in the book, unless noted

- Rotation through a fourth dimension can’t affect a three-dimensional figure any more than you can shake letters off a printed page.

- And He Built a Crooked House (p. 33)

- “Why do you like to play chess so well?”

“Because it is the only thing in the world where I can see all the factors and understand all the rules.”- They (p. 55)

- “People who looked like me and who should have felt very much like me, if what I was told was the truth. But what did they appear to be doing? ‘They went to work to earn the money to buy the food to get the strength to go to work to earn the money to buy the food to get the strength to go to work to get the strength to buy the food to earn the money to go to—’ until they fell over dead. Any slight basic variation in the basic pattern did not matter, for they always fell over dead. And everybody tried to tell me that I should be doing the same thing. I knew better!”

- They (pp. 55-56)

- It is true that most religions which have been offered me teach immortality, but note the fashion in which they teach it. The surest way to lie convincingly is to tell the truth unconvincingly. They did not wish me to believe.

- They (p. 60)

- It is very difficult to tuck a bugle call back into a bugle. Pandora’s Box is a one-way proposition. You can turn a pig into sausage, but not sausage into pig. Broken eggs stay broken.

- Solution Unsatisfactory (p. 67)

- Imperialism degrades both oppressor and oppressed.

- Solution Unsatisfactory (p. 98)

- There is no science of sociology. Perhaps there will be, some day, when a rigorous physics gives a finished science of colloidal chemistry and that leads in turn to a complete knowledge of biology, and from there to a definitive psychology. After that we may begin to know something about sociology and politics. Sometime around the year 5000 A.D., maybe—if the human race does not commit suicide before then.

- Solution Unsatisfactory (p. 98)

- “The trouble with you youngsters,” Joe said, “is that if you can’t understand a thing right off, you think it can’t be true. The trouble with your elders is, anything they didn’t understand they reinterpreted to mean something else and then thought they understood it. None of you has tried believing clear words the way they were written and then tried to understand them on that basis. Oh, no, you’re all too bloody smart for that—if you can’t see it right off, it ain’t so—it must mean something different.”

- Universe (p. 119)

- It is an emotional impossibility for any man to believe in his own death.

- Elsewhen (p. 152)

- “I think that’s unfair, Doctor. You certainly don’t expect a man to believe in things that run contrary to his good sense without offering him any reasonable explanation.”

Frost snorted. “I certainly do—if he has observed it with his own eyes and ears, or gets it from a source known to be credible. A fact doesn’t have to be understood to be true. Sure, any reasonable mind wants explanations, but it’s silly to reject facts that don’t fit your philosophy.”- Elsewhen (pp. 161-162)

- “But that’s not possible!”

Frost looked more weary than ever. Don’t you think it is about time you stopped using that term, son?”- Elsewhen (p. 164)

- Narby had no particular respect for engineers, largely because he had no particular talent for engineering.

- Elsewhen (p. 182)

- Bob Wilson admitted to himself that a Ph.D. and an appointment as an instructor was not his idea of existence. Still, it beat working for a living.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 234)

- In Wilson’s scale of evaluations breakfast rated just after life itself and ahead of the chance of immortality.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 238)

- Like many a man before him, he found himself forced into a lie because the truth simply would not be believed.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 243)

- Is it not better to be in ignorance than to believe falsely?

- By His Bootstraps (p. 249)

- Time after time he had fallen into the Cartesian fallacy, mistaking clear reasoning for correct reasoning.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 257)

- He thought of a way to state it: Ego is the point of consciousness, the latest term in a continuously expanding series along the line of memory duration. That sounded like a general statement, but he was not sure; he would have to try to formulate it mathematically before he could trust it. Verbal language had such queer booby traps in it.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 257)

- Free will was another matter. It could not be laughed off, because it could be directly experienced—yet his own free will had worked to create the same scene over and over again. Apparently human will must be considered as one of the factors which make up the processes in the continuum—”free” to the ego, mechanistic from the outside.

- By His Bootstraps (p. 271)

- When I was a young student, I thought modern psychology could tell me the answers, but I soon found out that the best psychologists didn’t know a damn thing about the real core of the matter. Oh, I am not disparaging the work that has been done; it was badly needed and had been very useful in its way. None of ’em know what life is, what thought is, whether free will is a reality or an illusion, or whether that last question means anything. The best of ’em admit their ignorance; the worst of them make dogmatic assertions that are obvious absurdities.

- Lost Legacy (p. 284)

- In the first place there isn’t a distinguished anthropologist in the world but what you’ll find one equally distinguished who will call him a diamond-studded liar. They can’t agree on the simplest elements of their alleged science.

- Lost Legacy (p. 301)

- Convinced of their destiny to rule, they convinced themselves that the end justified the means.

- Lost Legacy (p. 315)

- “We see the history of the world as a series of crises in a conflict between two opposing philosophies. Ours is based on the notion that life, consciousness, intelligence, ego is the important thing in the world.”...“That puts us in conflict with every force that tends to destroy, deaden, degrade the human spirit, or to make it act contrary to its nature.”

- Lost Legacy (p. 318; ellipsis represents a minor elision of description)

- Cold calculated awareness that their power lay in keeping the people in ignorance.

- Lost Legacy (p. 333)

- And all over the country the antagonists of human liberty, of human dignity—the racketeers, the crooked political figures, the shysters, the dealers in phony religions, the sweat-shoppers, the petty authoritarians, all of the key figures among the traffickers in human misery and human oppression, themselves somewhat adept in the arts of the mind and acutely aware of the danger of free knowledge—all of this unholy breed stirred uneasily and wondered what was taking place.

- Lost Legacy (p. 339)

- For vice has this defect; it cannot be truly intelligent. Its very motives are its weakness.

- Lost Legacy (p. 339)

- Good government grows out of the people; it cannot be handed to them.

- My Object All Sublime (p. 357)

- A half hour later I had a headache and a plan, but it called for an accomplice. The plan, I mean. The headache I could manage alone.

- My Object All Sublime (p. 360)

- He had the high degree of courage so common in the human race, a race capable of conceiving death, yet able to face its probability daily, on the highway, on the obstetrics table, on the battlefield, in the air, in the subway—and to face lightheartedly the certainty of death in the end.

- Goldfish Bowl (p. 381)

- It takes all nations to keep the peace, but it only takes one to start a war.

- Free Men (p. 414)

- “Joe, I’ve learned by bitter experience not to trust statements set off by ‘naturally,’ ‘of course,’ or ‘that goes without saying.’”

- Free Men (p. 418)

- No, chum, there’s a lot of guff talked about freedom. No man is free. There is no such thing as freedom. There are only various privileges.

- Free Men (p. 425)

- There’s one thing this has taught me: You can’t enslave a free man. Only person can do that to a man is himself. No, sir—you can’t enslave a free man. The most you can do is kill him.

- Free Men (p. 430)

- He was beginning definitely to dislike Mrs. Van Vogel, despite his automatic tendency to genuflect in the presence of a high credit rating.

- Free Men (p. 450)

- Men! Their minds were devious—they seemed to like twisted ways of doing things. It confirmed her opinion that men should not be allowed to vote.

- Jerry Was a Man (p. 458)

- “Mooncraft isn’t a game; it’s the real thing. ‘Did you stay alive?’ If you make a mistake, you flunk—and they bury you.”

- Nothing Ever Happens on the Moon (p. 485)

- “If you know any prayers, better say them.”

Sam shook his arm. “It’s not time to pray; it’s time to get busy.”- Nothing Ever Happens on the Moon (p. 497)

- A man without cash had one arm in a sling.

- Gulf (p. 525)

- Luck is a bonus that follows careful planning—it’s never free.

- Gulf (p. 534)

- “Man is not a rational animal; he is a rationalizing animal.

“For explanations of a universe that confuses him he seizes onto numerology, astrology, hysterical religions, and other fancy ways to go crazy. Having accepted such glorified nonsense, facts make no impression on him, even if at the cost of his own life. Joe, one of the hardest things to believe is the abysmal depth of human stupidity.”- Gulf (p. 542)

- “For a hundred and fifty years or so democracy, or something like it, could flourish safely. The issues were such as to be settled without disaster by votes of common men, befogged and ignorant as they were. But now, if the race is simply to stay alive, political decisions depend on real knowledge of such things as nuclear physics, planetary ecology, genetic theory, even system mechanics. They aren’t up to it, Joe. With goodness and more will than they possess less than one in a thousand could stay awake over one page of nuclear physics; they can’t learn what they must know.”

- Gulf (p. 544)

- Reason is poor propaganda when opposed by the yammering, unceasing lies of shrewd and evil and self-serving men. The little man has no way to judge and the shoddy lies are packaged more attractively. There is no way to offer color to a colorblind man, nor is there any way for us to give the man of imperfect brain the canny skill to distinguish a lie from a truth.

- Gulf (p. 544)

- A totalitarian political religion is incompatible with free investigation.

- Gulf (p. 545)

- The arrangement, classification, and accessibility of knowledge remains in all ages the most pressing problem.

- Gulf (p. 555)

- Don’t say that I don’t mix with the common people, Joe; I sell used ’copters for a living. You can’t get any commoner. And don’t imply that my heart is not with them. We are not like them, but we are tied to them by the strongest bond of all, for we are all, each every one, sickening with the same certainly fatal disease—we are alive.

- Gulf (pp. 556-557)

- Apparently she believes she is safe. Evil is essentially stupid, Joe; despite her brilliance, she believes what she wishes to believe. Or it may be that she is willing to risk her own death against the tempting prize of absolute power.

- Gulf (p. 559)

- “Jim, you’re a fool,”Bowles answered.

“No, I’m a bachelor. Why? Because I can’t stand the favorite sport of all women.”

“Which is?”

“Trying to geld stallions. Let’s get on with the job.”- Destination Moon (p. 570)

- “They’re crazy.”

“No, Meade. One such is crazy; a lot of them is a lemming death march.”- The Year of the Jackpot (p. 622)

- To be sure, some humans were always doing silly things—but at what point had prime damfoolishness become commonplace? When for example, had the zombie-like professional models become accepted ideals of American womanhood?

- The Year of the Jackpot (p. 628)

- “But you were right!”

“Since when has being right endeared a man to his boss?”- The Year of the Jackpot (p. 632)

- Aside from mathematics, just two things worth doing—kill a man and love a woman. He had done both; he was rich.

- The Year of the Jackpot (p. 642)

- What good is the race of man? Monkeys, he thought, monkeys with a spot of poetry in them, cluttering and wasting a second-string planet near a third-string star. But sometimes they finish in style.

- The Year of the Jackpot (p. 644)

- Earth, seen from space, looked as it had looked in color-stereo pictures, but he found that the real thing is as vastly more satisfying as a hamburger is better than a picture of one.

- A Tenderfoot in Space (p. 689)

- “Funny sort of science! I guess they were pretty ignorant in those days.”

“Don’t go running down our grandfathers. If it weren’t for them, you and I would be squatting in a cave, scratching fleas. No, Bub, they were pretty sharp; they just didn’t have all the facts. We’ve got more facts, but that doesn’t make us smarter.”- A Tenderfoot in Space (p. 691)

- “I don’t like cats.”

“Ever lived with a cat? No, I see you haven’t. How can you have the gall not to like something you don’t know anything about? Wait till you’ve lived with a cat, then tell me what you think. Until then...well, who told you you were entitled to an opinion?”

“Huh? Why, everybody is entitled to his own opinion!”

“Nonsense, Bub. Nobody is entitled to an opinion about something he is ignorant of. If the Captain told me how to bake a cake, I would politely suggest that he not stick his nose into my trade...contrariwise, I never tell him how to plan an orbit to Mars.”- A Tenderfoot in Space (p. 692)

- Hundred dollar bills have a hypnotic effect on a person not used to them.

- —All You Zombies— (p. 732)

Rocket Ship Galileo (1947)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ace Books (#73330)

- Hans had courage to burn. If he had been willing to knuckle under to the Nazis he would have stayed at Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. But Hans was a scientist. He wouldn’t trim his notion of truth to fit political gangsters.

- Chapter 4, “The Blood of Pioneers”, p. 34

- “I was just trying to show you,” he went on, “just how insubstantial a ‘common sense’ idea can be when you pin it down. Neither ‘common sense’ nor ‘logic’ can prove anything. Proof comes from experiment, or to put it another way, from experience, and from nothing else.”

- Chapter 10, “The Method of Science”, p. 105

- “You know the answers, but just between ourselves, that sketch smells a bit. It’s sloppy.”

“I never did have any artistic talent,” Art said defensively. “I’d rather take a photograph any day.”

“You’ve taken too many photographs, maybe. As for artistic talent, I haven’t any either, but I learned to sketch. Look, Art—the rest of you guys get this, too—if you can’t sketch, you can’t see. If you really see what you’re looking at, you can put it down on paper, accurately. If you really remember what you have looked at, you can sketch it accurately from memory.”

“But the lines don’t go where I intend them to.”

“A pencil will go where you push it. It hasn’t any life of its own. The answer is practice and more practice and thinking about what you are looking at. All of you lugs want to be scientists. Well, the ability to sketch accurately is as necessary to a scientist as his slipstick. More necessary, you can get along without a slide rule.”- Chapter 10, “The Method of Science”, p. 108

Beyond This Horizon (1948; originally serialized in 1942)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Signet (Q5695)

- The door dilated.

- Chapter 1, “All of them should have been very happy—”, p. 5 and several other times

- This offhand mention has become the simplest (three words!) and often-quoted exposition of the wonders of a different world, where what would be novel today has become simply the way things work.

- “He posed me a question which I must answer correctly—else he will not co-operate.”

“Huh? What was the question?

“I’ll ask you. Martha, what is the meaning of life?”

“What! Why, what a stupid question!”

“He did not ask it stupidly.”

“It’s a psychopathic question, unlimited, unanswerable, and, in all probability, sense free.”- Chapter 2, “Rich Man, Poor Man, Beggar Man, Thief—”, p. 35; see also pages 31, 33

- Since when did a mathematician need any tools but his own head? Pythagoras had done well enough with a stick and a stretch of sand.

- Chapter 4, “Boy meets Girl”, p. 45

- “Can I trust you, my friend?”

“If you can’t, then what is my assurance worth?”- Chapter 4, “Boy meets Girl”, p. 48

- “But what you’re talking about means giving up all that—just the noble primitive, simple and self-sufficient. He’s going to chop down a tree—who sold him the ax? He wants to shoot a deer—who made his gun?...There never was and there never could be a noble simple creature such as you described. He’d be an ignorant savage, with dirt on his skin and lice in his hair. He would work sixteen hours a day to stay alive at all. He’d sleep in a filthy hut on a dirt floor. And his point of view and his mental processes would be just two jumps above an animal.”

- Chapter 6, “We don’t speak the same lingo”, pp. 73-74

- Babies are fun. And they’re not much trouble. Feed ‘em occasionally, help them when they need it, and love them a lot. That’s all there is to it.

- Chapter 7, “Burn him down at once—”, p. 75

- So-called instincts are instructive, Felix. They point to survival values.

- Chapter 7, “Burn him down at once—”, p. 76

- The police of a state should never be stronger or better armed than the citizenry. An armed citizenry, willing to fight, is the foundation of civil freedom. That’s a personal evaluation, of course.

- Chapter 9, “When we die, do we die all over?”, p. 97

- I venture to predict that, when we get around to reviewing their records, we will find that the rebels were almost all—all, perhaps—men who had never been outstandingly successful at anything. Their only prominence was among themselves.

- Chapter 10, “—the only game in town”, p. 104

- “If there was anything, anything more at all, after this crazy mix-up we call living, I could feel that there might be some point to the whole frantic business, even if I did not know and could not know the full answer while I was alive.”

“And suppose there was not? Suppose that when a man’s body disintegrates, he himself disappears absolutely. I’m bound to say I find it a probable hypothesis.”

“Well— It wouldn’t be cheerful knowledge, but it would be better than not knowing. You could plan your life rationally, at least. A man might even be able to get a certain amount of satisfaction in planning things better for the future, after he’s gone. A vicarious pleasure in the anticipation.”- Chapter 10, “—the only game in town”, p. 105

- Hamilton took a deep breath, let it out, then said, “Listen to me. I don’t know much about women, and sometimes it seems like I didn’t know anything about them. But I’m sure of this—she won’t let a little thing like you taking a pot shot at her stand in the way if you ever had any chance with her at all. She’ll forgive you.”

“You don’t really mean that, do you?” Monroe-Alpha’s face was still tragic, but he clutched at the hope.

“Certainly I do. Women will forgive anything.” With a flash of insight he added, “Otherwise the race would have died out long ago.”- Chapter 10, “—the only game in town”, pp. 108-109

- There is no subject inappropriate for scientific research. Johann, we’ve let you fellows have a monopoly of such matters for too long. The most serious questions in the world have been left to faith or speculation. It is time for scientists to cope with them, or admit that science is no more than pebble counting.

- Chapter 11, “—then a man is something more than his genes!”, p. 111

- Protoplasm is protean; any simple protoplasm can become any complex form of life under mutation and selection.

- Chapter 13, “No more privacy than a guppy in an aquarium”, p. 126

- “The Great Egg must love human beings, he made a lot of them.”

“Same argument applies to oysters, only more so.”- Chapter 13, “No more privacy than a guppy in an aquarium”, p. 127

- Oh, we get along. She lets me have my own way, and later I find out I’ve done just what she wanted me to do.

- Chapter 14, “—and beat him when he sneezes”, p. 130

- At fourteen months he began speaking in sentences, short and of his own structure, but sentences. The subjects of his conversation, or, rather, his statements, were consistently egocentric. Normal again—no one expects an infant to write essays on the beauties of altruism.

- Chapter 14, “—and beat him when he sneezes”, p. 131

- Theobald ignored him. He could be deaf when he chose; he seemed to find it particularly difficult to hear the word “No.”

- Chapter 14, “—and beat him when he sneezes”, p. 132

- Natural selection—the dying out of the poorly equipped—goes on day in and day out, inexorable and automatic. It is as tireless, as inescapable, as entropy.

- Chapter 14, “—and beat him when he sneezes”, p. 134

- “What of it? I’d still be myself. I don’t care what people think.”

“You’re mistaken, son. To believe that you can live free of your cultural matrix is one of the easiest fallacies and has some of the worst consequences. You are part of your group whether you like it or not, and you are bound by its customs.”- Chapter 15, “Probably a blind alley—”, p. 146

- Well, in the first place an armed society is a polite society. Manners are good when one may have to back up his acts with his life. For me, politeness is a sine qua non of civilization. That’s a personal evaluation only. But gunfighting has a strong biological use. We do not have enough things to kill off the weak and the stupid these days. But to stay alive as an armed citizen a man has to be either quick with his wits or with his hands, preferably both. It’s a good thing.

- Chapter 15, “Probably a blind alley—”, p. 147

Space Cadet (1948)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Del Rey Books (#26072)

- Wong shook his head sadly. “I sometimes think that modern education is deliberately designed to handicap a boy.”

- Chapter 6 “Reading, and ’riting, and ’rithmetic—”, p. 71

- A military hierarchy automatically places a premium on conservative behavior and dull conformance with precedent; it tends to penalize original and imaginative thinking.

- Chapter 9 “Long Haul”, p. 101

- “People tend to fall into three psychological types, all differently motivated. There is the type, motivated by economic factors, money...And there is the type motivated by ‘face,’ or pride. This type is a spender, fighter, boaster, lover, sportsman, gambler; he has a will to power and an itch for glory. And there is the professional type, which claims to follow a code of ethics rather than simply seeking money or glory—priests and ministers, teachers, scientists, medical men, some artists and writers. The idea is that such a man believes that he is devoting his life to some purpose more important than his individual self. You follow me?”

- Chapter 9 “Long Haul”, p. 111

- Matt, you are suffering from a disease of youth—you expect moral problems to have nice, neat, black-and-white answers.

- Chapter 10 “Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?”, p. 126

- The sort of guardian you can hire is worth about as much as the sort of wife you can buy.

- Chapter 12 “P.R.S. Pathfinder”, p. 143

- “I wish Doc Pickering was here.”

“Yeah, and if fish had feet, they’d be mice.”- Chapter 14 “The Natives are Friendly...”, p. 160

- Precedent is merely the assumption that somebody else, in the past with less information, nevertheless knows better than the man on the spot.

- Chapter 15 “Pie With a Fork”, p. 180

- “Sometimes I think,” he told Tex, “that Th’Wing thinks that I am an idiot studying hard to become a moron—but flunking the course.”

- Chapter 16 “P.R.S. Astarte”, p. 195

Red Planet (1949)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ace Books (#71140)

- “Jim?”

“Yes, Dad.”

“What’s this about leaving your gun where the baby could reach it?”

Jim flushed. “It wasn’t charged, Dad.”

“If all the people who had been killed with unloaded guns were laid end to end it would make quite a line up. You are proud of being a licensed gun wearer, aren’t you?

“Uh, yes, sir.”

“And I’m proud to have you be one. It means you are a responsible, trusted adult. But when I sponsored you before the Council and stood up with you when you took your oath, I guaranteed that you would obey the regulations and follow the code, wholeheartedly and all the time—not just most of the time. Understand me?”

“Yes, sir. I think I do.”- Chapter 2, “South Colony, Mars”, pp. 16-17

- Never listen to newscasts. Saves wear and tear on the nervous system.

- Chapter 2, “South Colony, Mars”, p. 17

- Doc says the Company set-up is just one big happy family, and the idea that it is a non-profit corporation is the biggest joke since women were invented.

- Chapter 4, “Lowell Academy”, p. 44

- Every law that was ever written opened up a new way to graft.

- Chapter 4, “Lowell Academy”, p. 49

- I’m not going to give up my gun. Dad wouldn’t want me to. I’m sure of that. Anyhow, I’m licensed and I don’t have to. I’m a qualified marksman, I’ve passed the psycho tests, and I’ve taken the oath; I’m as much entitled to wear a gun as he is.

- Chapter 4, “Lowell Academy”, p. 55

- “He’ll pay no mind to me anyhow,” MacRae answered. “That’s the healthy thing about kids.”

- Chapter 9, “Politics”, p. 133

- I found out a long time ago that you have to take some chances in this life. Otherwise you are just a vegetable, headed for the soup pot.

- Chapter 10, “We’re Boxed In!”, p. 145

- “You put me in mind of a case I ran into in the American West. A respected citizen shot a professional gunthrower in the back. When asked why he didn’t give the other chap a chance to draw, the survivor said, ‘Well, he’s dead and I’m alive and that’s how I wanted it to be.’ Jamie, if you use sportsmanship on a known scamp, you put yourself at a terrible disadvantage.”

- Chapter 10, “We’re Boxed In!”, p. 148

Sixth Column (1949; originally serialized in 1941)

[edit]- Reprinted often with the alternative title The Day After Tomorrow. All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Signet (T4227) using this alternate title, fourth printing

- “Thanks, awfully,” said Thomas. “Now...uh...what do I owe you for this?”

Finney’s reaction made him feel as if he had uttered some indecency. “Don’t mention payment, my son! Money is wrong—it’s the means whereby man enslaves his brother.”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” Thomas apologized sincerely. “Nevertheless, I wish there were some way for me to do something for you.”

“That is another matter. Help your brother when you can, and help will come to you when you need it.”- Chapter 2 (pp. 24-25)

- Three things only do slaves require, food, work, and their gods, and of the three their gods must never be touched, else they grow troublesome.

- Chapter 5 (p. 57)

- These savages and their false gods! I grow weary of them. Yet they are necessary; the priests and the gods of slaves always fight on the side of the Masters. It is a rule of nature.

- Chapter 5 (p. 62)

- They made a good team. As a matter of fact their talents were not too far apart; the artist is two-thirds artisan and the artisan has essentially the same creative urge as the artist.

- Chapter 5 (p. 68)

- We don’t have to be convincing—not in the sense of getting converts. Real converts might prove to be a nuisance. We just have to be convincing enough to look like a legitimate religion to our overlords. And that doesn’t have to be very convincing. All religions look equally silly from the outside.

- Chapter 6 (p. 70)

- “Scheer, are you any good at counterfeiting?”

“I’ve never tried it, sir.”

“No time like the present. Every man needs an alternative profession.”- Chapter 6 (p. 72)

- Sex is rearing its interesting head.

- Chapter 7 (p. 83)

- A man has to grow up in a language to be able to understand it scrambled.

- Chapter 9 (p. 108)

- When had a slave religion proved anything but an aid to the conqueror? Slaves needed a wailing wall; they went into their temples, prayed to their gods to deliver them from oppression, and came out to work in the fields and factories, relaxed and made harmless by the emotional catharsis of prayer.

- Chapter 9 (p. 108)

- Any cipher can be broken, any code can be compromised. But the most exact academic knowledge of a language gives no clue to its slang, its colloquial allusions, its half statements, over statements, and inverted meanings.

- Chapter 9 (p. 113)

- “What sort of a remark?”

“Just priestly mumbo-jumbo. Impressive and no real meaning. Can you do it?”

“I think so—I used to sell magazine subscriptions.”- Chapter 10 (p. 127)

- “Look, Chief—is it really necessary to kill everybody here? I don’t relish it.”

“Don’t get chicken, son,” admonished Ardmore with an edge in his voice. “This is war—and war is no joke. There is no such thing as a humane war.”- Chapter 10 (p. 129)

Farmer in the Sky (1950)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Dell (#2518), first printing (February 1968)

- “People have a funny habit of taking as ‘natural’ whatever they are used to—but there hasn’t been any ‘natural’ environment, the way they mean it, since men climbed down out of trees.”

- Chapter 2, “The Green-Eyed Monster” (p. 21)

- I think girls should be raised in the bottom of a deep, dark sack until they are old enough to know better.

- Chapter 4, “Captain DeLongPre” (p. 50)

- I looked it up later; he was right. Dad is an absolute mine of useless information. He says a fact should be loved for itself alone.

- Chapter 9, “The Moons of Jupiter” (pp. 90-91)

- See how involved it gets? Clover, bees, nitrogen, escape speed, power, plant-animal balance, gas laws, compound interest laws, meteorology—a mathematical ecologist has to think of everything and think of it ahead of time. Ecology is explosive; what seems like a minor and harmless invasion can change the whole balance.

- Chapter 12, “Bees and Zeroes” (p. 125)

- It was so darn quiet you could hear your hair grow.

- Chapter 13, “Johnny Appleseed” (p. 131)

- Bill, why is it that some apparently-grown men never learn to do simple arithmetic?

- Chapter 14, “Land of My Own” (p. 142)

- Pioneers need good neighbors.

- Chapter 14, “Land of My Own” (p. 147)

- For three hundred years the race had glazed windows. Then they shut themselves up in little air-conditioned boxes and stared at silly television pictures instead. One might as well be on Luna.

- Chapter 16, “Line Up” (p. 161)

- Gravity’s books have got to balance.

- Chapter 17, “Disaster” (p. 177)

- Horses can manufacture more horses and that is one trick that tractors have never learned.

- Chapter 18, “Pioneer Party” (p. 187)

- You can only grieve so much; after that it’s self pity.

- Chapter 18, “Pioneer Party” (p. 188)

- I said, “What do you think about it, Paul?”

The boss smiled gently. “I don’t. I haven’t enough data.”- Chapter 18, “Pioneer Party” (pp. 193-194)

- Life is not merely persistent, as Jock puts it; life is explosive. The basic theorem of population mathematics to which there has never been found an exception is that population increases always, not merely up to the extent of the food supply, but beyond it, to the minimum diet that will sustain life—the ragged edge of starvation.

- Chapter 18, “Pioneer Party” (p. 196)

- I’m not raising any kids to be radioactive dust.

- Chapter 18, “Pioneer Party” (p. 198)

- I’m going to put it to you straight. Never mind about being chief engineer of a planet; these days even a farmer needs the best education he can get. Without it he’s just a country bumpkin, a stumbling peasant, poking seeds into the ground and hoping a miracle will make them grow.

- Chapter 20, “Home” (pp. 218-219)

The Puppet Masters (1951)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Signet (#W7339)

- There is one thing no head of a country can know, and that is: how good is his intelligence system? He finds out only by having it fail him.

- Chapter 1 (p. 7)

- The Old Man’s unique gift was the ability to reason logically with unfamiliar, hard-to-believe facts as easily with the commonplace. Not much, eh? Most minds stall dead when faced with facts which conflict with basic beliefs; “I-just-can’t-believe-it” is all one word to highbrows and dimwits alike.

- Chapter 3 (p. 20)

- There was nothing under her clothes but girl and assorted items of lethal hardware.

- Chapter 4 (p. 28)

- “Let me get this,” the Old Man said. “You are promising the human race that, if we will just surrender, you will take care of us and make us happy. Right?”

“Exactly!”

The Old Man studied this while looking past my shoulders. He spat on the floor. “You know,” he said slowly, “me and my kind, we have often been offered that bargain. It never worked out worth a damn.”- Chapter 10 (p. 58)

- Mary? After all, what was she? Just another babe. True, I was disgusted with her for letting herself be used as bait. It was all right for her to use her femaleness as an agent; the Section had to have female operatives. There have always been female spies, and the young and pretty ones have always used the same tools.

- Chapter 10 (p. 61)

- Listen, son—most women are damn fools and children. But they’ve got more range than we’ve got. The brave ones are braver, the good ones are better—and the vile ones are viler.

- Chapter 11 (p. 65)

- McIlvaine continued, “Take the amoeba—a more basic, and much more successful life form than ours. The motivational psychology of the amoeba—”

I switched off my ears; free speech gives a man the right to talk about the “psychology” of an amoeba, but I don’t have to listen.- Chapter 19 (p. 104)

- Marriage is not ownership and wives are not property.

- Chapter 21 (p. 116)

- The matter was still "Top Secret" and the subject of cabinet debates at the time of the Scranton Riot. Don't ask me why it was top secret, or even restricted; our government has gotten the habit of classifying anything as secret which the all-wise statesmen and bureaucrats decide we are not big enough boys and girls to know, a Mother-Knows-Best-Dear policy. I've read that there used to be a time when a taxpayer could demand the facts on anything and get them. I don't know; it sounds Utopian.

- Chapter 24 (p. 127)

- “What is a ‘hunch’?”

“Eh? It’s a belief that something is so, or isn’t so, without evidence.”

“I’d call a hunch the result of automatic reasoning below the conscious level on data you did not know you possessed.”- Chapter 28 (p. 149)

- In the army it takes an eight-man working party to help a brass hat blow his nose.

- Chapter 30 (p. 153)

- I don’t believe in luck, Sam. Luck is a tag given by the mediocre to account for the accomplishments of genius.

- Chapter 30 (p. 158)

- Beat the plowshares back into swords; the other was a maiden aunt’s fancy.

- Chapter 35 (p. 174)

Between Planets (1951)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Del Rey Books (#27796)

- He was still having trouble readjusting. Wars were something you studied, not something that actually happened.

- Chapter 1, “New Mexico” (p. 9)

- Don, have you been dealing with a booklegger?

- Chapter 1, “New Mexico” (p. 10) - Mr. Reeves, asking the main character why he was in possession of a forbidden book discussing interplanetary politics.

- Everything is theoretically impossible, until it’s done. One could write a history of science in reverse by assembling the solemn pronouncements of highest authority about what could not be done and could never happen.

- Chapter 2, “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin” (p. 23)

- The point is, your request for a lawyer comes about two hundred years too late to be meaningful. The verbalisms lag behind the facts. Nevertheless, you shall have a lawyer—or a lollipop, whichever you prefer, after I am through questioning you. If I were you, I’d take the lollipop. More nourishing.

- Chapter 3, “Hunted” (p. 38) - Secret Service officer to the main character during an interrogation.

- He considered horoscopes as silly as spectacles on a cow.

- Chapter 4, “The Glory Road” (p. 43)

- He had let himself be bulldozed by the odds against him. He promised himself never again to pay any attention to the odds, but only to the issues.

- Chapter 4, “The Glory Road” (p. 45)

- Mercifully, we stay our hand. Earth’s cities will not be bombed. The free citizens of Venus Republic have no wish to slaughter their cousins still on Terra. Our only purpose is to establish our own independence, to manage our own affairs, to throw off the crushing yoke of absentee ownership and taxation without representation which has bleed us poor.

In doing so, in so taking our stand as free men, we call on all oppressed and impoverished nations everywhere to follow our lead, accept our help. Look up into the sky! Swimming there above you is the very station from which I now address you. The fat and stupid rulers of the Federation have made of Circum-Terra an overseer’s whip. The threat of this military base in the sky has protected their empire from the just wrath of their victims for more then five score years.

We now crush it.

In a matter of minutes this scandal in the clean skies, this pistol pointed at the heads of men everywhere on your planet, will cease to exist. Step out of doors, watch the sky. Watch a new sun blaze briefly, and know that its light is the light of Liberty inviting all of Earth to free itself.

Subject peoples of Earth, we free men of the free Republic of Venus salute you with that sign!- Chapter 6, “The Sign in the Sky” (p. 74) - Speech given before the destruction of the nuclear-armed satellite Circum-Terra.

- A second sun blazed white and swelled visibly as he watched. What on Earth would have been—so many times had been—a climbing mushroom cloud was here in open space a perfect geometrical sphere, growing unbelievably. It swelled still larger, dropping from limelight white to to silvery violet, became blotched with purple, red and flame. And still it grew, until it blanked out the earth beyond it.

At the time it had been transformed into a radioactive cosmic cloud Circum-Terra had been passing over, or opposite, the North Atlantic; the swollen incandescent cloud was visible to most of the habitable portions of the globe, a burning symbol in the sky.- Chapter 6, “The Sign in the Sky” (p. 75)

- Man needs freedom, but few men are so strong as to be happy with complete freedom. A man needs to be part of a group, with accepted and respected relationships. Some men join foreign legions for adventure; still more swear on a bit of paper in order to acquire a framework of duties and obligations, customs and taboos, a time to work and a time to loaf, a comrade to dispute with and a sergeant to hate—in short, to belong.

- Chapter 7, “The Detour” (p. 83)

- Don took it and said, “Uh, thanks! That’s awfully kind of you. I’ll pay it back, first chance.”

“Instead, pay it forward to some other brother who needs it.”- Chapter 8, “Foxes Have Holes, and Birds of the Air Have Nests—” (p. 91)

- The attack should not have happened, of course. The rice farmer sergeant had been perfectly right; the Federation could not afford to risk its own great cites to punish the villagers of Venus. He was right—from his viewpoint.

A rice farmer has one logic; the men who live by and for power have another and entirely different logic. Their lives are built on tenuous assumptions, fragile as reputation; they could not afford to ignore a challenge to their power—the Federation could not afford not to punish the insolent colonists.- Chapter 10, “While I Was Musing the Fire Burned” (p. 113)

- He gave up and went back to loafing, found that he could sleep all right in the afternoons but that the practice kept him awake at night.

- Chapter 17, “To Reset the Clock” (p. 173)

- Chief, perhaps it would be clearest to say that the fasarta modulates the garbab in such a phase relationship that the thrimaleen is forced to bast—or, to put it another way, somebody loosed mice in the washroom. Seriously, there is no popular way to explain it. If you were willing to spend five hard years with me, working up through the math, I could probably bring you to the same level of ignorance and confusion that I enjoy.

- Chapter 17, “To Reset the Clock” (p. 176)

- She grabbed him by both ears and kissed him quickly, then ran away.

Don stared after her, rubbing his mouth. Girls, he reflected, were much odder than dragons. Probably another race entirely.- Chapter 18, “Little David” (p. 182)

I know their faults and I know that their virtues far outweigh their faults.

- Written for the Edward R. Murrow radio show, This I Believe (1952) - full transcript and audio online

- I am not going to talk about religious beliefs, but about matters so obvious that it has gone out of style to mention them.

I believe in my neighbors.

I know their faults and I know that their virtues far outweigh their faults. Take Father Michael down our road a piece — I'm not of his creed, but I know the goodness and charity and lovingkindness that shine in his daily actions. I believe in Father Mike; if I'm in trouble, I'll go to him. My next-door neighbor is a veterinary doctor. Doc will get out of bed after a hard day to help a stray cat. No fee — no prospect of a fee. I believe in Doc.

- Decency is not news; it is buried in the obituaries — but it is a force stronger than crime.

I believe in the patient gallantry of nurses...in the tedious sacrifices of teachers. I believe in the unseen and unending fight against desperate odds that goes on quietly in almost every home in the land.

- I believe in the honest craft of workmen. Take a look around you. There never were enough bosses to check up on all that work. From Independence Hall to the Grand Coulee Dam, these things were built level and square by craftsmen who were honest in their bones.

- I believe that almost all politicians are honest. For every bribed alderman there are hundreds of politicians, low paid or not paid at all, doing their level best without thanks or glory to make our system work. If this were not true, we would never have gotten past the thirteen colonies.

- I believe in — I am proud to belong to — the United States. Despite shortcomings, from lynchings to bad faith in high places, our nation has had the most decent and kindly internal practices and foreign policies to be found anywhere in history.

And finally, I believe in my whole race. Yellow, white, black, red, brown — in the honesty, courage, intelligence, durability … and goodness … .of the overwhelming majority of my brothers and sisters everywhere on this planet. I am proud to be a human being. I believe that we have come this far by the skin of our teeth, that we always make it just by the skin of our teeth — but that we will always make it … survive … endure. I believe that this hairless embryo with the aching, oversize brain case and the opposable thumb, this animal barely up from the apes, will endure — will endure longer than his home planet, will spread out to the other planets, to the stars, and beyond, carrying with him his honesty, his insatiable curiosity, his unlimited courage — and his noble essential decency.

This I believe with all my heart.

The Rolling Stones (1952)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Del Rey Books (#27581) ISBN 0-87997-350-1

- Every technology goes through three stages: first a crudely simple and quite unsatisfactory gadget; second, an enormously complicated group of gadgets designed to overcome the shortcomings of the original and achieving thereby somewhat satisfactory performance through extremely complex compromise; third, a final stage of smooth simplicity and efficient performance based on correct understanding of natural laws and proper design therefrom.

- Chapter 4, “Aspects of Domestic Engineering” (pp. 52-53)

- Mr. Stone was satisfied, being sure in his heart that any person skilled with mathematical tools could learn anything else he needed to know, with or without a master.

- Chapter 4, “Aspects of Domestic Engineering” (p. 61)

- If you’re going to be businessmen, don’t confuse the vocation with larceny.

- Chapter 4, “Aspects of Domestic Engineering” (p. 61)

- “You have us going faster than light.”

“I thought the figures were a bit large.”- Chapter 8, “The Mighty Room” (p. 100)

- The situation has multifarious ramifications not immediately apparent to the unassisted optic.

- Chapter 13, “Caveat Vendor” (pp. 177-178)

- “It didn’t happen that way,” Roger Stone cut in, “so there is no use talking about other possibilities. They probably aren’t really possibilities at all, if only we understood it.”

Pollux: “Predestination.”

Castor: “Very shaky theory.”

Roger grinned. “I’m not a determinist and you can’t get my goat. I believe in free will.”

Pollux: “Another very shaky theory.”

“Make up your minds,” their father told them. “You can’t have it both ways.”

“Why not?” asked Hazel. “Free will is a golden thread running through the frozen matrix of fixed events.”

“Not mathematical,” objected Pollux.

Castor nodded. “Just poetry.”

“And not very good poetry.”- Chapter 14, “Flat Cats Factorial” (p. 182)

- Go ahead. Go right ahead. Don’t let me discourage you. Any objections from me would simply confirm your preconceptions.

- Chapter 14, “Flat Cats Factorial” (p. 187)

- Wherever there is power and mass to manipulate, Man can live.

- Chapter 16, “Rock City” (p. 208)

Starman Jones (1953)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ballantine Books (#24354) 1st printing (February 1975)

- But as grandpop always said, there are just three ways to get ahead; sweat and genius, getting born into the right family, or marrying into it.

- Chapter 8, “Three Ways to Get Ahead” (p. 82)

- Max opened his mouth, closed it, opened it again. “No.”

“Speak louder. You used a word I don’t understand.”- Chapter 9, “Chartman Jones” (p. 95)

- Everybody has a skeleton in the closet; the thing is to keep ’em there and not at the feast.

- Chapter 10, “Garson’s Planet” (p. 109)

- A distance “as the crow flies” is significant only to crows.

- Chapter 11, “Through the Cargo Hatch” (p. 111)

- Like searching at midnight in a dark cellar for a black cat that isn’t there.

- Chapter 11, “Through the Cargo Hatch” (p. 115)

- Sic transit gloria mundi—Tuesday is usually worse.

- Chapter 12, “Halcyon” (p. 135)

- Oh Max, you large lout, you arouse the eternal maternal in me.

- Chapter 17, “Charity” (p. 185)

- “You know, Ellie, you play this game awfully well—for a girl.”

“Thank you too much.”

“No, I mean it. I suppose girls are probably as intelligent as men, but most of them don’t act like it. I think it’s because they don’t have to. If a girl is pretty, she doesn’t have to think.”- Chapter 19, “A Friend in Need” (p. 210)

- “Mr. Jones, has it ever occurred to you, the world being what it is, that women sometimes prefer not to appear too bright?”

- Chapter 19, “A Friend in Need” (p. 211)

- “I guess I don’t understand women.”

“That’s an understatement.”- Chapter 19, “A Friend in Need” (p. 211)

The Star Beast (1954)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ace Books (#78001)

- The law is whatever you can convince a court it is.

- Chapter 3, “—An Improper Question” (p. 41)

- It seemed to John that most of the older people in the world spent much of their time not listening.

- Chapter 3, “—An Improper Question” (p. 53)

- Any organization calling itself “The Friends of This or That” always consisted of someone with an axe to grind, plus the usual assortment of prominent custard heads and professional stuffed shirts.

- Chapter 5, “A Matter of Viewpoint” (p. 82)

- “I talked with it, boss. It’s stupid.”

“I can’t see that you have established that. Assuming that an e.-t. is stupid because he can’t speak our language well is like assuming that an Italian is illiterate because he speaks broken English. A non-sequitur.”- Chapter 5, “A Matter of Viewpoint” (p. 87)

- If you can’t outargue the other fellow, sometimes you can outlive him.

- Chapter 6, “Space is Deep, Excellency” (p. 110)

- “May I say without offense that the reception given my sort on your great planet is sometimes something that one must be philosophical about?”

“I know. I’m sorry. My own people, most of them, are honestly convinced that the prejudices of their native village were ordained by the Almighty. I wish it were different.”- Chapter 6, “Space is Deep, Excellency” (p. 113)

- I do not like weapons, Doctor; they are the last resort of faulty diplomacy.

- Chapter 9, “Customs and an Ugly Duckling” (p. 151)

- “Heredity isn’t everything; I’m myself, an individual. You aren’t your parents. You’re not your father, you are not your mother. But you are a little late realizing it.” She sat up straight. “So be yourself, Knothead, and have the courage to make your own mess of your life. Don’t imitate somebody else’s mess.”

- Chapter 11, “It’s Too Late, Johnnie” (p. 170)

- Fact is, you work too hard...the universe won’t run down if you don’t wind it.

- Chapter 12, “Concerning Pidgie-Widgie” (p. 185)

- “You mean that, Henry?”

“I always mean what I say, sir. It saves time.”- Chapter 13, “No, Mr. Secretary” (p. 201)

- Madam, the commonest weakness of our race is our ability to rationalize our most selfish purposes.

- Chapter 14, “Destiny? Fiddlesticks!” (p. 219)

Tunnel in the Sky (1955)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ace Books (#82660)

- Remember, though, your best weapon is between your ears and under your scalp—provided it’s loaded.

- Chapter 1, “The Marching Hordes” (p. 14)

- Cut it out. If there is anything stupider that flogging yourself over something you can’t help, I’ve yet to meet it.

- Chapter 2, “The Fifth Way” (p. 40)

- When a cat greets you, he makes a big operation of it, bumping, stropping your legs, buzzing like mischief. But when he leaves, he just walks off and never looks back. Cats are smart.

- Chapter 2, “The Fifth Way” (p. 42)

- Man is not a rational animal; he is a rationalizing animal.

- Chapter 2, “The Fifth Way” (p. 42)

- One time in a hundred a gun might save your life; the other ninety-nine it will just tempt you into folly.

- Chapter 2, “The Fifth Way” (p. 43)

- “From the ignoramuses we get for recruits I’ve reached the conclusion that this new-fangled ‘functional education’ has abolished studying in favor of developing their cute little personalities.”

- Chapter 2, “The Fifth Way” (pp. 43-44)

- ""Good stories are rarely true."

- Chapter 3, "Through the Tunnel"

- Shaving, the common cold, and taxes...my old man says those are the three eternal problems the race is never going to lick.

- Chapter 6, “I Think He Is Dead” (p. 93)

- When you haven’t data, guessing is illogical.

- Chapter 6, “I Think He Is Dead” (p. 98)

- Rod...were you born that stupid? Or did you have to study?

- Chapter 6, “I Think He Is Dead” (p. 104)

- But don’t say you don’t need money; that’s immoral.

- Chapter 15, “In Achilles’ Tent” (p. 234)

Time for the Stars (1956)

[edit]- All page numbers from the mass market paperback edition published by Ace Books (#81125)

- I was confused. I didn’t feel telepathic; I merely felt hungry.

- Chapter 2, “The Natural Logarithm of Two” (p. 24)

- “Pat, can’t you get it through your thick head to leave well enough alone?”

“I don’t see what’s wrong with my logic.”

“Since when was an emotional argument won by logic?”- Chapter 4, “Half a Loaf” (p. 44)

- When it comes down to it, the root cause of war is always population pressure no matter what other factors enter in.

- Chapter 4, “Half a Loaf” (p. 44)

- I don’t know; maybe Frank had good intentions, but I sometimes think “good intentions” should be declared a capital crime.

- Chapter 5, “The Party of the Second Part” (p. 52)

- Parents probably don’t know that they are playing favorites even when they are doing it.

- Chapter 5, “The Party of the Second Part” (p. 54)

- I decided not to cross any bridges I had burned behind me.

- Chapter 7, “19,900 Ways” (p. 69)

- Learning isn’t a means to an end; it is an end in itself.

- Chapter 7, “19,900 Ways” (p. 70)

- Attend me. How do you prove that there are eggs in a bird’s nest? Don’t strain your gray matter: go climb the tree and find out. There is no other way.

- Chapter 8, “Relativity” (p. 82)

- You have to believe evidence when you have it in front of you, or else the universe is just too fantastic.

- Chapter 12, “Tau Ceti” (p. 122)

- “Harry, I need advice.”

“You do? Well, I’ve got it in all sizes. All of it free and all of it worth what it costs, I’m afraid.”- Chapter 15, “Carry Out Her Mission!” (p. 162)

Double Star (1956)

[edit]- Aside from a cold appreciation of my own genius I felt that I was a modest man.

- I have never been impressed by the formal schools of ethics. I had sampled them — public libraries are a ready source of recreation for an actor short of cash — but I had found them as poor in vitamins as a mother-in-law’s kiss. Given time and plenty of paper, a philosopher can prove anything. I had the same contempt for the moral instruction handed to most children. Much of it is prattle and the parts they really seem to mean are dedicated to the sacred proposition that a “good” child is one who does not disturb mother’s nap and a “good” man is one who achieves a muscular bank account without getting caught. No, thanks!

- Take sides! Always take sides! You will sometimes be wrong — but the man who refuses to take sides must always be wrong.

- His bow to me must have been calculated on a slide rule; it suggested that I was about to be Supreme Minister but was not quite there yet, that I was his senior but nevertheless a civilian — then subtract five degrees for the fact that he wore the Emperor’s aiguillette on his right shoulder.

- Son, suppose you tend to your knitting and I tend to mine.

- People don’t really want change, any change at all — and xenophobia is very deep-rooted. But we progress, as we must — if we are to go out to the stars.

- There is solemn satisfaction in doing the best you can for eight billion people. Perhaps their lives have no cosmic significance, but they have feelings. They can hurt.

- Pacifism is a shifty doctrine under which a man accepts the benefits of the social group without being willing to pay - and claims a halo for his dishonesty

The Door Into Summer (1957)

[edit]

- Cats have no sense of humor, they have terribly inflated egos, and they are very touchy.

- Chapter 2

- My old man claimed that the more complicated the law the more opportunity for scoundrels.

- Chapter 5

- Paymasters come in only two sizes: one sort shows you where the book says that you can’t have what you've got coming to you; the second sort digs through the book until he finds a paragraph that lets you have what you need even if you don’t rate it.

- Chapter 5

- An invention is something that was “impossible” up to then—that’s why governments grant patents.

- Chapter 6

- I counted to ten slowly, using binary notation.

- Chapter 8

- By the laws of statistics we could probably approximate just how unlikely it is that it would happen. But people forget—especially those who ought to know better, such as yourself—that while the laws of statistics tell you how unlikely a particular coincidence is, they state just as firmly that coincidences do happen.

- Chapter 8

- I had taken a partner once before—but, damnation, no matter how many times you get your fingers burned, you have to trust people. Otherwise you are a hermit in a cave, sleeping with one eye open.

- Chapter 10

- “Er, will your grandmother tell that fib for you?”

“I guess so. Yes, I'm sure she will. She says people have to tell little white fibs or else people couldn’t stand each other. But she says fibs were meant to be used, not abused.”

“She sounds like a sensible person.”- Chapter 11

- They made the predictable fuss about taking a cat into a room and an autobellhop is not responsive to bribes—hardly an improvement. But the assistant manager had more flexibility in his synapses; He listened to reason as long as it was crisp and rustled.

- Chapter 12