J. B. Bury

Appearance

(Redirected from John Bagnell Bury)

John Bagnell Bury (16 October 1861 – 1 June 1927) was an Anglo-Irish historian, classical scholar, Medieval Roman historian and philologist. He was Erasmus Smith's Professor of Modern History at Trinity College Dublin (1893–1902), before being Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge from 1902 until his death.

Quotes

[edit]

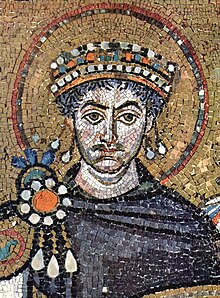

- Not long after his (Justinian) accession, he reaffirmed the penalties which previous Emperors had enacted against the pagans, and forbade all donations or legacies for the purpose of maintaining "Hellenic impiety,"...by making the profession of (Christian) orthodoxy a necessary condition for public teaching Justinian accelerated the extinction of "Hellenism." ... This event had a curious sequel. Some of the philosophers whose occupation was gone resolved to cast the dust of the Christian Empire from their feet and migrate.

- History of the Later Roman Empire, Chapter XXII, ECCLESIASTICAL POLICY, § 3. The Suppression of Paganism. University of Chicago.

The Ancient Greek Historians (1909)

[edit]- Writing the history of the present is always a very different thing from writing the history of the distant past. The history of the distant past depends entirely on literary and documentary sources; the history of the present always involves unwritten material as well as documents. But the difference was much greater in the days of Thucydides than it is now.

- Polybius is not less express than Thucydides in asserting the principle that accurate representation of facts was the fundamental duty of the historian. He lays down that three things are requisite for performing such a task as his: the study and criticism of sources; autopsy, that is, personal knowledge of lands and places; and thirdly, political experience.

A History of Greece to the Death of Alexander the Great (1913)

[edit]- The Achaeans of north Greece, which was later to be called Thessaly, seem to have been the great sea-adventurers of the heroic age. With this country were connected the memories of early Greek exploration of the Euxine, in the legend of the ship Argo. And to the Achaeans of Thessaly we must probably refer the earliest notice which preserves the Achaean name in a historical document. An Egyptian writing tells us that they came in company with other peoples "from the lands of the sea" and invaded Egypt in the year 1229 B.C., when Memptah was king. But the great achievement which made the Achaeans illustrious was one in which southern and northern Greece combined—the expedition against Troy.

- The Macedonian people and their kings were of Greek stock, as their traditions and the scanty remains of their language combine to testify.

A History of Freedom of Thought (1913)

[edit]- Most beliefs about nature and man, which were not founded on scientific observation, have served directly or indirectly religious and social interests, and hence they have been protected by force against the criticisms of persons who have the inconvenient habit of using their reason.

- Some people speak as if we were not justified in rejecting a theological doctrine unless we can prove it false. But the burden of proof does not lie upon the rejecter. I remember a conversation in which, when some disrespectful remark was made about hell, a loyal friend of that establishment said triumphantly, "But, absurd as it may seem, you cannot disprove it." If you were told that in a certain planet revolving around Sirius there is a race of donkeys who speak the English language and spend their time in discussing eugenics, you could not disprove the statement, but would it, on that account, have any claim to be believed? Some minds would be prepared to accept it, if it were reiterated often enough, through the potent force of suggestion.

- p.20

- It has been said that Homer was the Bible of the Greeks. The remark exactly misses the truth. The Greeks fortunately had no Bible, and this fact was both an expression and an important condition of their freedom. Homer's poems were secular, not religious, and it may be noted that they are freer from immorality and savagery than sacred books that one could mention.

- Socrates was the greatest of the educationalists, but unlike the others he taught gratuitously, though he was a poor man. His teachings always took the form of discussion; the discussion often ended in no positive result, but had the effect of showing that some received opinion was untenable and the truth is difficult to ascertain.

The Idea of Progress: An Inquiry Into Its Origin and Growth (1921)

[edit]- Science has been advancing without interruption during the last three of four hundred years; every new discovery has led to new problems and new methods of solution, and opened up new fields for exploration. Hitherto men of science have not been compelled to halt, they have always found ways to advance further. But what assurance have we that they will not come up against impassable barriers? ...Take biology or astronomy. How can we be sure that some day progress may not come to a dead pause, not because knowledge is exhausted, but because our resources for investigation are exhausted... It is an assumption, which cannot be verified, that we shall not reach a point in our knowledge of nature beyond which the human intellect is unqualified to pass.

- Introduction

- The doubts that Mr. Balfour expressed nearly thirty years ago, in an Address delivered in Glasgow, have not, so far, been answered. And it is probable that many people, to whom six years ago the notion of a sudden decline or break-up of our western civilisation, as a result not of cosmic forces but of its own development, would have appeared almost fantastic, will feel much less confident to-day, notwithstanding the fact that the leading nations of the world have instituted a league of peoples for the prevention of war, the measure to which so many high priests of Progress have looked forward as meaning a long stride forward on the road to Utopia.

- referring to Arthur Balfour's A Fragment on Progress (1891)

Quotes about Bury

[edit]- It is clear that in all these examples, which I have taken at random up and down the book, the writer is doing what we so continually find upon the part of academic authorities, particularly when they are indulging in an attack upon the Catholic Church—he is repeating what some other man of the same kind has said before him, and that other man is repeating something that was said before him. He has not been at the pains of consulting original authorities; and the result is valueless and inaccurate history, always wrong and sometimes the exact opposite of the truth.

- Hilaire Belloc, in an essay criticising Bury's historical accuracy in A History of Freedom of Thought