Edgar Rice Burroughs

Appearance

(Redirected from Tarzan of the Apes)

Edgar Rice Burroughs (1 September 1875 – 19 March 1950) was an American author of science-fiction and adventure stories, most famous for the creation of the jungle-born hero Tarzan.

Quotes

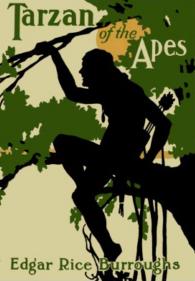

[edit]Tarzan of the Apes (1912)

[edit]

- I had this story from one who had no business to tell it to me, or to any other. I may credit the seductive influence of an old vintage upon the narrator for the beginning of it, and my own skeptical incredulity during the days that followed for the balance of the strange tale.

- First lines, Ch. 1 : Out to Sea

- I do not say the story is true, for I did not witness the happenings which it portrays, but the fact that in the telling of it to you I have taken fictitious names for the principal characters quite sufficiently evidences the sincerity of my own belief that it may be true.

The yellow, mildewed pages of the diary of a man long dead, and the records of the Colonial Office dovetail perfectly with the narrative of my convivial host, and so I give you the story as I painstakingly pieced it out from these several various agencies.

If you do not find it credible you will at least be as one with me in acknowledging that it is unique, remarkable, and interesting.- Ch. 1 : Out to Sea

- There were mothers and brothers and sisters, and aunts and cousins to express various opinions on the subject, but as to what they severally advised history is silent.

We know only that on a bright May morning in 1888, John, Lord Greystoke, and Lady Alice sailed from Dover on their way to Africa.

A month later they arrived at Freetown where they chartered a small sailing vessel, the Fuwalda, which was to bear them to their final destination.

And here John, Lord Greystoke, and Lady Alice, his wife, vanished from the eyes and from the knowledge of men.- Ch. 1 : Out to Sea

- On the fifth day following the murder of the ship's officers, land was sighted by the lookout. Whether island or mainland, Black Michael did not know, but he announced to Clayton that if investigation showed that the place was habitable he and Lady Greystoke were to be put ashore with their belongings.

- Ch. 2 : The Savage Home

- That night a little son was born in the tiny cabin beside the primeval forest, while a leopard screamed before the door, and the deep notes of a lion's roar sounded from beyond the ridge.

Lady Greystoke never recovered from the shock of the great ape's attack, and, though she lived for a year after her baby was born, she was never again outside the cabin, nor did she ever fully realize that she was not in England.- Ch. 3 : Life and Death

- In his leisure Clayton read, often aloud to his wife, from the store of books he had brought for their new home. Among these were many for little children — picture books, primers, readers — for they had known that their little child would be old enough for such before they might hope to return to England.

- Ch. 3 : Life and Death

- Kala was the youngest mate of a male called Tublat, meaning broken nose, and the child she had seen dashed to death was her first; for she was but nine or ten years old.

- Ch. 4 : The Apes

- Noiselessly Kerchak entered, crouching for the charge; and then John Clayton rose with a sudden start and faced them.

The sight that met his eyes must have frozen him with horror, for there, within the door, stood three great bull apes, while behind them crowded many more; how many he never knew, for his revolvers were hanging on the far wall beside his rifle, and Kerchak was charging.

When the king ape released the limp form which had been John Clayton, Lord Greystoke, he turned his attention toward the little cradle; but Kala was there before him, and when he would have grasped the child she snatched it herself, and before he could intercept her she had bolted through the door and taken refuge in a high tree.

- High up among the branches of a mighty tree she hugged the shrieking infant to her bosom, and soon the instinct that was as dominant in this fierce female as it had been in the breast of his tender and beautiful mother — the instinct of mother love — reached out to the tiny man-child's half-formed understanding, and he became quiet.

Then hunger closed the gap between them, and the son of an English lord and an English lady nursed at the breast of Kala, the great ape.- Ch. 4 : The Apes

- Tenderly Kala nursed her little waif, wondering silently why it did not gain strength and agility as did the little apes of other mothers. It was nearly a year from the time the little fellow came into her possession before he would walk alone, and as for climbing — my, but how stupid he was!

- Ch. 5 : The White Ape

- As Tarzan grew he made more rapid strides, so that by the time he was ten years old he was an excellent climber, and on the ground could do many wonderful things which were beyond the powers of his little brothers and sisters.

In many ways did he differ from them, and they often marveled at his superior cunning, but in strength and size he was deficient; for at ten the great anthropoids were fully grown, some of them towering over six feet in height, while little Tarzan was still but a half-grown boy.- Ch. 5 : The White Ape

- Though but ten years old he was fully as strong as the average man of thirty, and far more agile than the most practiced athlete ever becomes. And day by day his strength was increasing.

His life among these fierce apes had been happy; for his recollection held no other life, nor did he know that there existed within the universe aught else than his little forest and the wild jungle animals with which he was familiar.

He was nearly ten before he commenced to realize that a great difference existed between himself and his fellows. His little body, burned brown by exposure, suddenly caused him feelings of intense shame, for he realized that it was entirely hairless, like some low snake, or other reptile.- Ch. 5 : The White Ape

- In Tarzan's clever little mind many thoughts revolved, and back of these was his divine power of reason.

If he could catch his fellow apes with his long arm of many grasses, why not Sabor, the lioness?- Ch. 5 : The White Ape

- The story of his own connection with the cabin had never been told him. The language of the apes had so few words that they could talk but little of what they had seen in the cabin, having no words to accurately describe either the strange people or their belongings, and so, long before Tarzan was old enough to understand, the subject had been forgotten by the tribe.

Only in a dim, vague way had Kala explained to him that his father had been a strange white ape, but he did not know that Kala was not his own mother.- Ch. 6 : Jungle Battles

- In the middle of the floor lay a skeleton, every vestige of flesh gone from the bones to which still clung the mildewed and moldered remnants of what had once been clothing. Upon the bed lay a similar gruesome thing, but smaller, while in a tiny cradle near-by was a third, a wee mite of a skeleton.

To none of these evidences of a fearful tragedy of a long dead day did little Tarzan give but passing heed. His wild jungle life had inured him to the sight of dead and dying animals, and had he known that he was looking upon the remains of his own father and mother he would have been no more greatly moved.- Ch. 6 : Jungle Battles

- Among other things he found a sharp hunting knife, on the keen blade of which he immediately proceeded to cut his finger. Undaunted he continued his experiments, finding that he could hack and hew splinters of wood from the table and chairs with this new toy.

- Ch. 6 : Jungle Battles

- In a cupboard filled with books he came across one with brightly colored pictures — it was a child's illustrated alphabet — A is for Archer Who shoots with a bow. B is for Boy, His first name is Joe. The pictures interested him greatly.

There were many apes with faces similar to his own, and further over in the book he found, under "M," some little monkeys such as he saw daily flitting through the trees of his primeval forest. But nowhere was pictured any of his own people; in all the book was none that resembled Kerchak, or Tublat, or Kala.- Ch. 6 : Jungle Battles

- The boats, and trains, and cows and horses were quite meaningless to him, but not quite so baffling as the odd little figures which appeared beneath and between the colored pictures — some strange kind of bug he thought they might be, for many of them had legs though nowhere could he find one with eyes and a mouth. It was his first introduction to the letters of the alphabet, and he was over ten years old.

- Ch. 6 : Jungle Battles

- He commenced a systematic search of the cabin; but his attention was soon riveted by the books which seemed to exert a strange and powerful influence over him, so that he could scarce attend to aught else for the lure of the wondrous puzzle which their purpose presented to him.

Among the other books were a primer, some child's readers, numerous picture books, and a great dictionary. All of these he examined, but the pictures caught his fancy most, though the strange little bugs which covered the pages where there were no pictures excited his wonder and deepest thought.- Ch. 7 : The Light of Knowledge

- His little face was tense in study, for he had partially grasped, in a hazy, nebulous way, the rudiments of a thought which was destined to prove the key and the solution to the puzzling problem of the strange little bugs.

In his hands was a primer opened at a picture of a little ape similar to himself, but covered, except for hands and face, with strange, colored fur, for such he thought the jacket and trousers to be. Beneath the picture were three little bugs — BOY.- Ch. 7 : The Light of Knowledge

- Slowly he turned the pages, scanning the pictures and the text for a repetition of the combination B-O-Y. Presently he found it beneath a picture of another little ape and a strange animal which went upon four legs like the jackal and resembled him not a little. Beneath this picture the bugs appeared as: A BOY AND A DOG There they were, the three little bugs which always accompanied the little ape.

And so he progressed very, very slowly, for it was a hard and laborious task which he had set himself without knowing it — a task which might seem to you or me impossible — learning to read without having the slightest knowledge of letters or written language, or the faintest idea that such things existed.

He did not accomplish it in a day, or in a week, or in a month, or in a year; but slowly, very slowly, he learned after he had grasped the possibilities which lay in those little bugs, so that by the time he was fifteen he knew the various combinations of letters which stood for every pictured figure in the little primer and in one or two of the picture books.- Ch. 7 : The Light of Knowledge

- Tarzan held a peculiar position in the tribe. They seemed to consider him one of them and yet in some way different. The older males either ignored him entirely or else hated him so vindictively that but for his wondrous agility and speed and the fierce protection of the huge Kala he would have been dispatched at an early age.

- Ch. 7 : The Light of Knowledge

- One by one the tribe swung down from their arboreal retreats and formed a circle about Tarzan and his vanquished foe. When they had all come Tarzan turned toward them.

"I am Tarzan," he cried. "I am a great killer. Let all respect Tarzan of the Apes and Kala, his mother. There be none among you as mighty as Tarzan. Let his enemies beware."- Ch. 7 : The Light of Knowledge

- Tarzan of the Apes lived on in his wild, jungle existence with little change for several years, only that he grew stronger and wiser, and learned from his books more and more of the strange worlds which lay somewhere outside his primeval forest.

- Ch. 9 : Man and Man

- To him life was never monotonous or stale. There was always Pisah, the fish, to be caught in the many streams and the little lakes, and Sabor, with her ferocious cousins to keep one ever on the alert and give zest to every instant that one spent upon the ground.

Often they hunted him, and more often he hunted them, but though they never quite reached him with those cruel, sharp claws of theirs, yet there were times when one could scarce have passed a thick leaf between their talons and his smooth hide.

Quick was Sabor, the lioness, and quick were Numa and Sheeta, but Tarzan of the Apes was lightning.

- Thus, at eighteen, we find him, an English lordling, who could speak no English, and yet who could read and write his native language. Never had he seen a human being other than himself, for the little area traversed by his tribe was watered by no greater river to bring down the savage natives of the interior.

High hills shut it off on three sides, the ocean on the fourth. It was alive with lions and leopards and poisonous snakes. Its untouched mazes of matted jungle had as yet invited no hardy pioneer from the human beasts beyond its frontier.- Ch. 9 : Man and Man

- Tarzan was an interested spectator. His desire to kill burned fiercely in his wild breast, but his desire to learn was even greater. He would follow this savage creature for a while and know from whence he came. He could kill him at his leisure later, when the bow and deadly arrows were laid aside.

- Ch. 9 : Man and Man

- He had seen fire, but only when Ara, the lightning, had destroyed some great tree. That any creature of the jungle could produce the red-and-yellow fangs which devoured wood and left nothing but fine dust surprised Tarzan greatly, and why the black warrior had ruined his delicious repast by plunging it into the blighting heat was quite beyond him. Possibly Ara was a friend with whom the Archer was sharing his food.

But, be that as it may, Tarzan would not ruin good meat in any such foolish manner, so he gobbled down a great quantity of the raw flesh, burying the balance of the carcass beside the trail where he could find it upon his return.- Ch. 9 : Man and Man

- Tarzan must act quickly or his prey would be gone; but Tarzan's life training left so little space between decision and action when an emergency confronted him that there was not even room for the shadow of a thought between.

- Ch. 9 : Man and Man

- Tarzan of the Apes was no sentimentalist. He knew nothing of the brotherhood of man. All things outside his own tribe were his deadly enemies, with the few exceptions of which Tantor, the elephant, was a marked example.

And he realized all this without malice or hatred. To kill was the law of the wild world he knew. Few were his primitive pleasures, but the greatest of these was to hunt and kill, and so he accorded to others the right to cherish the same desires as he, even though he himself might be the object of their hunt.

His strange life had left him neither morose nor bloodthirsty. That he joyed in killing, and that he killed with a joyous laugh upon his handsome lips betokened no innate cruelty. He killed for food most often, but, being a man, he sometimes killed for pleasure, a thing which no other animal does; for it has remained for man alone among all creatures to kill senselessly and wantonly for the mere pleasure of inflicting suffering and death.

And when he killed for revenge, or in self-defense, he did that also without hysteria, for it was a very businesslike proceeding which admitted of no levity.- Ch. 10 : The Fear-Phantom

- Tarzan of the Apes knew that they had found the body of his victim, but that interested him far less than the fact that no one remained in the village to prevent his taking a supply of the arrows which lay below him.

- Ch. 10 : The Fear-Phantom

- Tarzan of the Apes, young and savage beast of the jungle, wondered at the cruel brutality of his own kind.

Sheeta, the leopard, alone of all the jungle folk, tortured his prey. The ethics of all the others meted a quick and merciful death to their victims.

Tarzan had learned from his books but scattered fragments of the ways of human beings.- Ch. 11 : "King of the Apes"

- Kerchak was dead.

Withdrawing the knife that had so often rendered him master of far mightier muscles than his own, Tarzan of the Apes placed his foot upon the neck of his vanquished enemy, and once again, loud through the forest rang the fierce, wild cry of the conqueror.

And thus came the young Lord Greystoke into the kingship of the Apes.- Ch. 11 : "King of the Apes"

- For months the life of the little band went on much as it had before, except that Tarzan's greater intelligence and his ability as a hunter were the means of providing for them more bountifully than ever before. Most of them, therefore, were more than content with the change in rulers.

- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- Now was the quiet, fierce solitude of the primeval forest broken by new, strange cries. No longer was there safety for bird or beast. Man had come.

Other animals passed up and down the jungle by day and by night — fierce, cruel beasts — but their weaker neighbors only fled from their immediate vicinity to return again when the danger was past.

With man it is different. When he comes many of the larger animals instinctively leave the district entirely, seldom if ever to return; and thus it has always been with the great anthropoids. They flee man as man flees a pestilence.- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- The duties of kingship among the anthropoids are not many or arduous. … But Tarzan tired of it, as he found that kingship meant the curtailment of his liberty. He longed for the little cabin and the sun-kissed sea — for the cool interior of the well-built house, and for the never-ending wonders of the many books.

As he had grown older, he found that he had grown away from his people. Their interests and his were far removed. They had not kept pace with him, nor could they understand aught of the many strange and wonderful dreams that passed through the active brain of their human king. So limited was their vocabulary that Tarzan could not even talk with them of the many new truths, and the great fields of thought that his reading had opened up before his longing eyes, or make known ambitions which stirred his soul.

Among the tribe he no longer had friends as of old. A little child may find companionship in many strange and simple creatures, but to a grown man there must be some semblance of equality in intellect as the basis for agreeable association.- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- Had Kala lived, Tarzan would have sacrificed all else to remain near her, but now that she was dead, and the playful friends of his childhood grown into fierce and surly brutes he felt that he much preferred the peace and solitude of his cabin to the irksome duties of leadership amongst a horde of wild beasts.

- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- Had there been no other personal attribute to influence the final outcome, Tarzan of the Apes, the young Lord Greystoke, would have died as he had lived — an unknown savage beast in equatorial Africa.

But there was that which had raised him far above his fellows of the jungle — that little spark which spells the whole vast difference between man and brute — Reason. This it was which saved him from death beneath the iron muscles and tearing fangs of Terkoz.- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- I am Tarzan, King of the Apes, mighty hunter, mighty fighter. In all the jungle there is none so great.

- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- Tarzan let him up, and in a few minutes all were back at their vocations, as though naught had occurred to mar the tranquility of their primeval forest haunts.

But deep in the minds of the apes was rooted the conviction that Tarzan was a mighty fighter and a strange creature. Strange because he had had it in his power to kill his enemy, but had allowed him to live — unharmed.- Ch. 12 : Man's Reason

- Tarzan of the Apes had decided to mark his evolution from the lower orders in every possible manner, and nothing seemed to him a more distinguishing badge of manhood than ornaments and clothing.

To this end, therefore, he collected the various arm and leg ornaments he had taken from the black warriors who had succumbed to his swift and silent noose, and donned them all after the way he had seen them worn.

About his neck hung the golden chain from which depended the diamond encrusted locket of his mother, the Lady Alice. At his back was a quiver of arrows slung from a leathern shoulder belt, another piece of loot from some vanquished black.

About his waist was a belt of tiny strips of rawhide fashioned by himself as a support for the home-made scabbard in which hung his father's hunting knife. The long bow which had been Kulonga's hung over his left shoulder.

The young Lord Greystoke was indeed a strange and war-like figure, his mass of black hair falling to his shoulders behind and cut with his hunting knife to a rude bang upon his forehead, that it might not fall before his eyes.

His straight and perfect figure, muscled as the best of the ancient Roman gladiators must have been muscled, and yet with the soft and sinuous curves of a Greek god, told at a glance the wondrous combination of enormous strength with suppleness and speed.- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- A personification, was Tarzan of the Apes, of the primitive man, the hunter, the warrior.

With the noble poise of his handsome head upon those broad shoulders, and the fire of life and intelligence in those fine, clear eyes, he might readily have typified some demigod of a wild and warlike bygone people of his ancient forest.

But of these things Tarzan did not think. He was worried because he had not clothing to indicate to all the jungle folks that he was a man and not an ape, and grave doubt often entered his mind as to whether he might not yet become an ape.- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- Only those who saw this terrible god of the jungle died; for was it not true that none left alive in the village had ever seen him? Therefore, those who had died at his hands must have seen him and paid the penalty with their lives.

As long as they supplied him with arrows and food he would not harm them unless they looked upon him, so it was ordered by Mbonga that in addition to the food offering there should also be laid out an offering of arrows for this Munan- go-Keewati, and this was done from then on.- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- The conduct of the white strangers it was that caused him the greatest perturbation. He puckered his brows into a frown of deep thought. It was well, thought he, that he had not given way to his first impulse to rush forward and greet these white men as brothers.

They were evidently no different from the black men — no more civilized than the apes — no less cruel than Sabor.- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- The last member of the party to disembark was a girl of about nineteen, and it was the young man who stood at the boat's prow to lift her high and dry upon land. She gave him a brave and pretty smile of thanks, but no words passed between them.

- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- DO NOT HARM THE THINGS WHICH ARE TARZAN'S. TARZAN WATCHES. TARZAN OF THE APES.

- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- Two keen eyes had watched every move of the party from the foliage of a nearby tree. Tarzan had seen the surprise caused by his notice, and while he could understand nothing of the spoken language of these strange people their gestures and facial expressions told him much.

- Ch. 13 : His Own Kind

- The poor dear cannot differentiate between erudition and wisdom.

- Ch. 17 : Burials

- Tarzan sat in a brown study for a long time after he finished reading the letter. It was filled with so many new and wonderful things that his brain was in a whirl as he attempted to digest them all.

So they did not know that he was Tarzan of the Apes. He would tell them.

In his tree he had constructed a rude shelter of leaves and boughs, beneath which, protected from the rain, he had placed the few treasures brought from the cabin. Among these were some pencils.

He took one, and beneath Jane Porter's signature he wrote: I am Tarzan of the Apes- Ch. 18 : The Jungle Toll

- Smiles are the foundation of beauty.

- Ch. 20 : Heredity

- Fingerprints prove you Greystoke. Congratulations. D'Arnot.

- Ch. 28 : Conclusion

- As Tarzan finished reading, Clayton entered and came toward him with extended hand.

Here was the man who had Tarzan's title, and Tarzan's estates, and was going to marry the woman whom Tarzan loved — the woman who loved Tarzan. A single word from Tarzan would make a great difference in this man's life.

It would take away his title and his lands and his castles, and — it would take them away from Jane Porter also. "I say, old man," cried Clayton, "I haven't had a chance to thank you for all you've done for us. It seems as though you had your hands full saving our lives in Africa and here.

"I'm awfully glad you came on here. We must get better acquainted. I often thought about you, you know, and the remarkable circumstances of your environment.

"If it's any of my business, how the devil did you ever get into that bally jungle?"

"I was born there," said Tarzan, quietly. "My mother was an Ape, and of course she couldn't tell me much about it. I never knew who my father was."- Ch. 28 : Conclusion

A Princess of Mars (1917)

[edit]- I have ever been prone to seek adventure and to investigate and experiment where wiser men would have left well enough alone.

- Chapter 5

- They are unfettered by precedent in the administration of justice. Customs have been handed down by ages of repetition, but the punishment for ignoring a custom is a matter for individual treatment by a jury of the culprit’s peers, and I may say that justice seldom misses fire, but seems rather to rule in inverse ratio to the ascendency of law. In one respect at least the Martians are a happy people; they have no lawyers.

- Chapter 9

- She has never harmed us, nor would she should we have fallen into her hands. It is only the men of her kind who war upon us, and I have ever thought that their attitude toward us is but the reflection of ours toward them. They live at peace with all their fellows, except when duty calls upon them to make war, while we are at peace with none; forever warring among our own kind as well as upon the red men, and even in our own communities the individuals fight amongst themselves. Oh, it is one continual, awful period of bloodshed from the time we break the shell until we gladly embrace the bosom of the river of mystery, the dark and ancient Iss which carries us to an unknown, but at least no more frightful and terrible existence! Fortunate indeed is he who meets his end in an early death. Say what you please to Tars Tarkas, he can mete out no worse fate to me than a continuation of the horrible existence we are forced to lead in this life.

- Chapter 9

- I sat for hours cross-legged, and cross-tempered, upon my silks meditating upon the queer freaks chance plays upon us poor devils of mortals.

- Chapter 14

- I verily believe that a man’s way with women is in inverse ratio to his prowess among men. The weakling and the saphead have often great ability to charm the fair sex, while the fighting man who can face a thousand real dangers unafraid, sits hiding in the shadows like some frightened child.

- Chapter 16

The Land That Time Forgot (1918)

[edit]- All quotes are from the public domain text of the novel, available at "The Land that Time Forgot"

- “There is only one place you can go,” von Schoenvorts sent word to me, “and that is Kiel. You can’t land anywhere else in these waters. If you wish, I will take you there, and I can promise that you will be treated well.”

“There is another place we can go,” I sent back my reply, “and we will before we’ll go to Germany. That place is hell.”- Chapter 2

- But metaphor, however poetic, never slaked a dry throat.

- Chapter 4

- I told them that it was obvious our very existence depended upon our unity of action, that we were to all intent and purpose entering a new world as far from the seat and causes of our own world-war as if millions of miles of space and eons of time separated us from our past lives and habitations.

“There is no reason why we should carry our racial and political hatreds into Caprona,” I insisted. “The Germans among us might kill all the English, or the English might kill the last German, without affecting in the slightest degree either the outcome of even the smallest skirmish upon the western front or the opinion of a single individual in any belligerent or neutral country. I therefore put the issue squarely to you all; shall we bury our animosities and work together with and for one another while we remain upon Caprona, or must we continue thus divided and but half armed, possibly until death has claimed the last of us?- Chapter 5

- Like all his kind and all other bullies, von Schoenvorts was a coward at heart.

- Chapter 6

- Miss La Rue was very quiet, though she replied graciously enough to whatever I had to say that required reply. I asked her if she did not feel well.

“Yes,” she said, “but I am depressed by the awfulness of it all. I feel of so little consequence—so small and helpless in the face of all these myriad manifestations of life stripped to the bone of its savagery and brutality. I realize as never before how cheap and valueless a thing is life. Life seems a joke, a cruel, grim joke. You are a laughable incident or a terrifying one as you happen to be less powerful or more powerful than some other form of life which crosses your path; but as a rule you are of no moment whatsoever to anything but yourself. You are a comic little figure, hopping from the cradle to the grave. Yes, that is our trouble—we take ourselves too seriously; but Caprona should be a sure cure for that.” She paused and laughed.

“You have evolved a beautiful philosophy,” I said. “It fills such a longing in the human breast. It is full, it is satisfying, it is ennobling. What wondrous strides toward perfection the human race might have made if the first man had evolved it and it had persisted until now as the creed of humanity.”

“I don’t like irony,” she said; “it indicates a small soul.”

“What other sort of soul, then, would you expect from ‘a comic little figure hopping from the cradle to the grave’?” I inquired. “And what difference does it make, anyway, what you like and what you don’t like? You are here for but an instant, and you mustn’t take yourself too seriously.”- Chapter 6

- She was a dear girl and a stanch and true comrade—more like a man than a woman.

- Chapter 9

- I was sure that Lys was dead. I wanted myself to die, and yet I clung to life—useless and hopeless and harrowing a thing as it had become. I clung to life because some ancient, reptilian forbear had clung to life and transmitted to me through the ages the most powerful motive that guided his minute brain—the motive of self-preservation.

- Chapter 9

- I was armed only with a hunting knife, and this I whipped from its scabbard as Kho leaped toward me. He was a mighty beast, mightily muscled, and the urge that has made males fight since the dawn of life on earth filled him with the blood-lust and the thirst to slay; but not one whit less did it fill me with the same primal passions. Two abysmal beasts sprang at each other’s throats that day beneath the shadow of earth’s oldest cliffs—the man of now and the man-thing of the earliest, forgotten then, imbued by the same deathless passion that has come down unchanged through all the epochs, periods and eras of time from the beginning, and which shall continue to the incalculable end—woman, the imperishable Alpha and Omega of life.

- Chapter 10

- That night the clouds broke, and the moon shone down upon our little ledge; and there, hand in hand, we turned our faces toward heaven and plighted our troth beneath the eyes of God. No human agency could have married us more sacredly than we are wed. We are man and wife, and we are content.

- Chapter 10

The People That Time Forgot (1918)

[edit]- All quotes are from the public domain text of the novel, available at "The People that Time Forgot"

- She was quite the most wonderful animal that I have ever looked upon, and what few of her charms her apparel hid, it quite effectively succeeded in accentuating.

- Chapter 2

- I was not at the time well enough acquainted with Caspakian ways to know that truthfulness and loyalty are two of the strongest characteristics of these primitive people. They are not sufficiently cultured to have become adept in hypocrisy, treason and dissimulation. There are, of course, a few exceptions.

- Chapter 4

- What was this hold she had upon me? Was I bewitched, that my mind refused to function sanely, and that judgment and reason were dethroned by some mad sentiment which I steadfastly refused to believe was love? I had never been in love. I was not in love now—the very thought was preposterous.

- Chapter 6

- I could have kicked myself for the snob and the cad that my thoughts had proven me—me, who had always prided myself that I was neither the one nor the other!

- Chapter 6

Out of Time's Abyss (1918)

[edit]- All quotes are from the public domain text of the novel, available at "Out of Time's Abyss"

- This was a new menace that threatened them, something that they couldn’t explain; and so, naturally, it aroused within them superstitious fear.

- Chapter 1

- Past experience suggested that the great wings were a part of some ingenious mechanical device, for the limitations of the human mind, which is always loath to accept aught beyond its own little experience, would not permit him to entertain the idea that the creatures might be naturally winged and at the same time of human origin.

- Chapter 2

- Thus Bradley reasoned—thus most of us reason; not by what might be possible; but by what has fallen within the range of our experience.

- Chapter 2

- All my life I have been kicked and cuffed by such as that, and yet always have I gone out when they commanded, singing, to give up my life if need be to keep them in power. Only lately have I come to know what a fool I have been. But now I am no longer a fool, and besides, I am avenged.

- Chapter 5

How I Wrote the Tarzan Books (1929)

[edit]- I have often been asked how I came to write. The best answer is that I needed the money. When I started I was 35 and had failed in every enterprise I had ever attempted.

- I sold electric light bulbs to janitors, candy to drug stores, and Stoddard's Lectures from door to door. I had decided I was a total failure, when I saw an advertisement which indicated that somebody wanted an expert accountant. Not knowing anything about its I applied for the job and got it.

I am convinced that what are commonly known as "the breaks," good or bad, have fully as much to do with one's success or failure as ability. The break I got in this instance lay in the fact that my employer knew even less about the duties of an expert accountant than I did.

- I determined there was a great future in the mail-order business, and I landed a job that brought me to the head of a large department. About this time our daughter Joan was born.

Having a good job and every prospect for advancement, I decided to go into business for myself, with harrowing results. I had no capital when I started and less when I got through. At this time the mail-order company offered me an excellent position if I wanted to come back If I had accepted it, I would probably have been fixed for life with a good living salary. Yet the chances are that I would never have written a story, which proves that occasionally it is better to do the wrong thing than the right.

When my independent business sank without a trace, I approached as near financial nadir as one may reach. My son, Hulbert, had just been born. I had no job, and no money. I had to pawn Mrs, Burroughs' jewelry and my watch in order to buy food. I loathed poverty, and I should have liked to have put my hands on the man who said that poverty is an honorable estate. It is an indication of inefficiency and nothing more. There is nothing honorable or fine about it. To be poor is quite bad enough. But to be poor without hope … well, the only way to understand it is to be it.

- I had gone thoroughly through some of the all-fiction magazines and I made up my mind that if people were paid for writing such rot as I read I could write stories just as rotten. Although I had never written a story, I knew absolutely that I could write stories just as entertaining and probably a lot more so than any I chanced to read in those magazines.

I knew nothing about the technique of story writing, and now, after eighteen years of writing, I still know nothing about the technique, although with the publication of my new novel, Tarzan and the Lost Empire, there are 31 books on my list. I had never met an editor, or an author or a publisher. l had no idea of how to submit a story or what I could expect in payment. Had I known anything about it at all I would never have thought of submitting half a novel; but that is what I did.

Thomas Newell Metcalf, who was then editor of The All-Story magazine, published by Munsey, wrote me that he liked the first half of a story I had sent him, and if the second half was as good he thought he might use it. Had he not given me this encouragement, I would never have finished the story, and my writing career would have been at an end, since l was not writing because of any urge to write, nor for any particular love of writing. l was writing because I had a wife and two babies, a combination which does not work well without money.

- No amount of money today could possibly give me the thrill that first $400 check gave me.

My first story was entitled, "Dejah Thoris, Princess of Mars." Metcalf changed it to "Under the Moons of Mars." It was later published in book form as A Princess of Mars.

- With the success of my first story, l decided to make writing a career, though I was canny enough not to give up my job. But the job did not pay expenses and we had a recurrence of great poverty, sustained only by the thread of hope that I might make a living writing fiction. I cast about for a better job and landed one as a department manager for a business magazine. While I was working there, I wrote Tarzan of the Apes, evenings and holidays. I wrote it in longhand on the backs of old letterheads and odd pieces of paper. I did not think it was a very good story and I doubted if it would sell. But Bob Davis saw its possibilities for magazine publication and I got a check … this time, l think, for $700.

- I had been trying to find a publisher who would put some of my stuff into book form, but I met with no encouragement. Every well-known publisher in the United States turned down Tarzan of the Apes, including A.C. McClurg & Co., who finally issued it, my first story in book form.