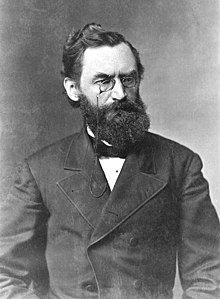

Carl Schurz

Appearance

Carl Christian Schurz (2 March 1829 – 14 May 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–49 and became a prominent member of the new Republican Party. After serving as a Union general in the American Civil War, he helped found the short-lived Liberal Republican Party and became a prominent advocate of civil service reform. Schurz represented Missouri in the United States Senate and was the 13th United States Secretary of the Interior.

Quotes

[edit]

- We have come to a point where it is loyalty to resist, and treason to submit.

- "State Rights and Byron Paine," Albany Hall, Milwaukee, (23 March 1859)

- Ideals are like stars; you will not succeed in touching them with your hands. But like the seafaring man on the desert of waters, you choose them as your guides, and following them you will reach your destiny.

- Address, Faneuil Hall, Boston (18 April 1859)

- I will make a prophecy that may now sound peculiar. In fifty years Lincoln's name will be inscribed close to Washington's on this Republic's roll of honor.

- Letter to Theodore Petrasch (12 October 1864)

- The animosities inflamed by a four years' war, and its distressing incidents, cannot be easily overcome. But they extend beyond the limits of the army, to the people of the north. I have read in southern papers bitter complaints about the unfriendly spirit exhibited by the northern people — complaints not unfrequently flavored with an admixture of vigorous vituperation. But, as far as my experience goes, the "unfriendly spirit" exhibited in the north is all mildness and affection compared with the popular temper which in the south vents itself in a variety of ways and on all possible occasions. No observing northern man can come into contact with the different classes composing southern society without noticing it. He may be received in social circles with great politeness, even with apparent cordiality; but soon he will become aware that, although he may be esteemed as a man, he is detested as a "Yankee," and, as the conversation becomes a little more confidential and throws off ordinary restraint, he is not unfrequently told so; the word "Yankee" still signifies to them those traits of character which the southern press has been so long in the habit of attributing to the northern people; and whenever they look around them upon the traces of the war, they see in them, not the consequences of their own folly, but the evidences of "Yankee wickedness." In making these general statements, I beg to be understood as always excluding the individual exceptions above mentioned.

It is by no means surprising that prejudices and resentments, which for years were so assiduously cultivated and so violently inflamed, should not have been turned into affection by a defeat; nor are they likely to disappear as long as the southern people continue to brood over their losses and misfortunes. They will gradually subside when those who entertain them cut resolutely loose from the past and embark in a career of new activity on a common field with those whom they have so long considered their enemies.

- The Senator from Wisconsin cannot frighten me by exclaiming, "My country, right or wrong." In one sense I say so too. My country; and my country is the great American Republic. My country, right or wrong; if right, to be kept right; and if wrong, to be set right.

- Remarks in the Senate (29 February 1872) He was here responding to the famous slogan derived from a statement of Stephen Decatur: "Our country! In her intercourse with foreign nations, may she always be in the right; but our country, right or wrong."

- What is the rule of honor to be observed by a power so strongly and so advantageously situated as this Republic is? Of course I do not expect it meekly to pocket real insults if they should be offered to it. But, surely, it should not, as our boyish jingoes wish it to do, swagger about among the nations of the world, with a chip on its shoulder, shaking its fist in everybody's face. Of course, it should not tamely submit to real encroachments upon its rights. But, surely, it should not, whenever its own notions of right or interest collide with the notions of others, fall into hysterics and act as if it really feared for its own security and its very independence.

As a true gentleman, conscious of his strength and his dignity, it should be slow to take offense. In its dealings with other nations it should have scrupulous regard, not only for their rights, but also for their self-respect. With all its latent resources for war, it should be the great peace power of the world. It should never forget what a proud privilege and what an inestimable blessing it is not to need and not to have big armies or navies to support. It should seek to influence mankind, not by heavy artillery, but by good example and wise counsel. It should see its highest glory, not in battles won, but in wars prevented. It should be so invariably just and fair, so trustworthy, so good tempered, so conciliatory, that other nations would instinctively turn to it as their mutual friend and the natural adjuster of their differences, thus making it the greatest preserver of the world's peace.

This is not a mere idealistic fancy. It is the natural position of this great republic among the nations of the earth. It is its noblest vocation, and it will be a glorious day for the United States when the good sense and the self-respect of the American people see in this their "manifest destiny." It all rests upon peace. Is not this peace with honor? There has, of late, been much loose speech about "Americanism." Is not this good Americanism? It is surely today the Americanism of those who love their country most. And I fervently hope that it will be and ever remain the Americanism of our children and our children's children.- Speech at the Chamber of Commerce, New York City, New York (2 January 1896)

- The man who in times of popular excitement boldly and unflinchingly resists hot-tempered clamor for an unnecessary war, and thus exposes himself to the opprobrious imputation of a lack of patriotism or of courage, to the end of saving his country from a great calamity, is, as to "loving and faithfully serving his country," at least as good a patriot as the hero of the most daring feat of arms, and a far better one than those who, with an ostentatious pretense of superior patriotism, cry for war before it is needed, especially if then they let others do the fighting.

- "About Patriotism," Harper’s Weekly (16 April 1898)

- I confidently trust that the American people will prove themselves … too wise not to detect the false pride or the dangerous ambitions or the selfish schemes which so often hide themselves under that deceptive cry of mock patriotism: "Our country, right or wrong!" They will not fail to recognize that our dignity, our free institutions and the peace and welfare of this and coming generations of Americans will be secure only as we cling to the watchword of true patriotism: "Our country — when right to be kept right; when wrong to be put right."

- Speech expanding upon his famous statement in the Senate many years before, at the Anti-Imperialistic Conference, Chicago, Illinois (17 October 1899)

Quotes about Carl Schurz

[edit]- Du Bois quotes the German American reformer Carl Schurz, who observed, “Wherever I go-the street, the shop, the house, the hotel, or the steamboat-I hear the people talk in such a way as to indicate that they are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all. Men who are honorable in their dealings with their white neighbors, will cheat a Negro without feeling a single twinge of their honor. To kill a Negro they do not deem murder; to debauch a Negro woman, they do not think fornication; to take the property away from a Negro they do not consider robbery."

- Cristina Beltrán Cruelty as Citizenship: How Migrant Suffering Sustains White Democracy (2020) p 59

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Carl Schurz on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Carl Schurz on Wikipedia Works related to Author:Carl Schurz on Wikisource

Works related to Author:Carl Schurz on Wikisource Media related to Carl Schurz on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carl Schurz on Wikimedia Commons- Works by Carl Schurz at Project Gutenberg

Categories:

- Ambassadors of the United States

- Members of the United States Senate

- Journalists from the United States

- Editors from the United States

- Non-fiction authors from the United States

- 1829 births

- 1906 deaths

- Revolutionaries

- Immigrants to the United States

- People from Cologne

- United States Secretaries of the Interior

- Republican Party (United States) politicians

- Political activists

- Generals of the Union Army