Chernobyl (miniseries)

Appearance

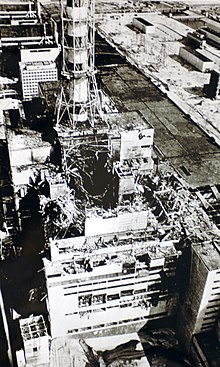

Chernobyl is a 2019 HBO miniseries based on the nuclear accident at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986.

- Directed by Johan Renck. Written by Craig Mazin.

"Then I'll do it myself." ~ Valery Legasov & Vladimir Pikalov

1:23:45 [1]

[edit]- [April 26, 1988: Alone in his apartment in Moscow, Professor Valery Legasov replays his voice on a tape recorder]

- Valery Legasov: What is the cost of lies? It's not that we'll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognize the truth at all. What can we do then? What else is left to abandon even the hope of truth and content ourselves instead with stories? In these stories, it doesn't matter who the heroes are. All we want to know is: "Who is to blame?" In this story, it was Anatoly Dyatlov. He was the best choice. An arrogant, unpleasant man, he ran the room that night, he gave the orders... and no friends. Or at least, not important ones. And now Dyatlov will spend the next ten years in a prison labor camp. Of course, that sentence is doubly unfair. There were far greater criminals than him at work. And as for what Dyatlov did do, the man doesn't deserve prison. He deserves death.

- [Legasov stops the tape, sips a glass of water, and then restarts the tape from where he left off.]

- Legasov: But instead, ten years for "criminal mismanagement". What does that mean? No one knows. It doesn't matter. What does matter is that, to them, justice was done. Because, you see, to them, a just world is a sane world. There was nothing sane about Chernobyl. What happened there, what happened after, even the good we did, all of it... all of it, madness. Well, I've given you everything I know. They'll deny it, of course. They always do. I know you'll try your best.

- [April 26, 1986: Immediately after the explosion, deputy chief engineer Anatoly Dyatlov stands shocked as shift supervisor Aleksandr Akimov calls his name repeatedly and alarms blare]

- Aleksandr Akimov: Comrade Dyatlov? Comrade Dyatlov?!

- Anatoly Dyatlov: What just happened?

- Leonid Toptunov: I don't know.

- [Turbine engineer Vyacheslav Brazhnik rushes into the room]

- Vyacheslav Brazhnik: There's a fire in the turbine hall.

- Dyatlov: The turbine hall... The control system tank. Hydrogen. [addressing Akimov] You and Toptunov, you morons blew the tank.

- Toptunov: No, that's not--

- Dyatlov: This is an emergency, everyone stay calm. Our first priority is to--

- [As Dyatlov speaks, foreman Valeriy Perevozchenko runs through the open door in a panic]

- Valeriy Perevozchenko: It exploded!

- Dyatlov: We know. Akimov, are we cooling the reactor core?

- Akimov: We shut it down, but the control rods are still... They're not all the way in, I disengaged the clutch --

- Dyatlov: Alright, I'll disconnect the servos from the standby console. [to two other engineers] You two, get the backup pumps running, we need water moving through the core, that is all that matters!

- Perevozchenko: There is no core! It exploded, the core exploded!

- [Beat as all the engineers stare at Perevozchenko in disbelief and fear]

- Dyatlov: He's in shock, get him out of here.

- Perevozchenko: The lid is off. The stack is burning, I saw it.

- Dyatlov: You're confused, RBMK reactor cores don't explode. Akimov! [picks up the phone to call out]

- Toptunov: [whispering, to Akimov] Sasha...

- Akimov: Don't worry, we did everything right. Something... something strange has happened.

- Toptunov: Do you taste metal?

- Dyatlov: Akimov!

- Akimov: [glances at Perevozchenko] Comrade Perevozchenko, what you're saying is physically impossible. The core can't explode. It has to be the tank.

- [Perevozchenko wordlessly shakes his head]

- Dyatlov: [hangs up the phone] We're wasting time. Let's go. Get the hydrogen out of the generators and pump water into the core.

- Brazhnik: What about the fire?

- Dyatlov: [annoyed; as if it were obvious] Call the fire brigade. [storms out]

- [April 26, 1986: Dyatlov meets with plant director Viktor Bryukhanov and chief engineer Nikolai Fomin in a bunker underneath the plant]

- Viktor Bryukhanov: [dryly] I take it the safety test was a failure.

- Anatoly Dyatlov: We have the situation under control.

- Nikolai Fomin: Under control? It doesn't look like it's under control.

- Bryukhanov: Shut up, Fomin. [to Dyatlov] I have to tell the Central Committee about this. Do you realize that? I have to get on the phone and tell Maryin, or God forbid Frolyshev, that my power plant is on fire.

- Dyatlov: No one can blame you for this, Director Bryukhanov

- Bryukhanov: Of course no one can blame me for this. How can I be responsible? I was sleeping. Tell me what happened. Quickly.

- Dyatlov: We ran the test exactly as Chief Engineer Fomin approved. Unit Shift Chief Akimov and Engineer Toptunov encountered technical difficulties, leading to an accumulation of hydrogen in the control system tank. It, regrettably, ignited, damaging the plant and setting the roof on fire.

- [Bryukhanov looks to Fomin]

- Fomin: The tank is quite large, yes. It's the only logical explanation. Of course, Deputy Chief Engineer Dyatlov was directly supervising the test, so he would know best.

- Bryukhanov: A hydrogen tank, fire...Reactor?

- Dyatlov: We're taking measures to ensure a steady flow of water through the core.

- Bryukhanov: What about radiation?

- Dyatlov: Obviously, down here it's nothing, but in the reactor building, I'm being told 3.6 roentgen per hour

- Bryukhanov: Well, that's not great, but it's not horrifying.

- Fomin: Not at all. From the feedwater, I assume?

- [Dyatlov nods]

- Fomin: We'll have to limit shifts to six hours at a time, but otherwise...

- Bryukhanov: The dosimetrists should be checking regularly. Have them use the good meter, from the safe. Right, I'll call Maryin. Have them wake up the local committee, there'll be orders coming down.

- Anatoly Dyatlov: I dropped the rods from the other panel

- Aleksandr Akimov: They're still up.

- Dyatlov: What?

- Akimov: They're still only a third of the way in, I don't know why. I already sent the trainees down to the reactor hall to lower them by hand.

- Dyatlov: What about the pumps?

- Leonid Toptunov: I can't get through to Khodemchuk, the lines are down.

- Dyatlov: Fuck the phones and fuck Khodemchuk. Are the pumps on or not?

- Akimov: Stolyarchuk?

- Boris Stolyarchuk: My control panel's not working. I tried calling for the electricians--

- Dyatlov: I don't give a shit about the panel! I need water in my reactor core! Get down there and make sure those pumps are on. Now!

- [several engineers leave the control room as Dyatlov sits down at a desk]

- Dyatlov: What does the dosimeter say?

- Akimov: Ah, 3.6 roentgen, but that's as high as the meter--

- Dyatlov: 3.6. Not great, not terrible.

- Akimov: [quietly, to Toptunov] We did everything right.

- [April 26, 1986: Meeting in the power plant office, engineer Anatoly Sitnikov reports high radiation in reactor 4]

- Dyatlov: What's wrong with you? How'd you get that number from feedwater leaking from a blown tank?

- Anatoly Sitnikov: You don't.

- Dyatlov: Then what the fuck are you talking about?

- Sitnikov: I... [clears throat] I walked around the exterior of building 4. I think there's graphite on the ground in the rubble.

- Dyatlov: You didn't see graphite.

- Sitnikov: I did.

- Dyatlov: You didn't. YOU DIDN'T! Because it's NOT THERE!

- Nikolai Fomin: What, are you suggesting the core... what? Exploded?

- Sitnikov: [almost a whisper] Yes.

- Fomin: Sitnikov, you're a nuclear engineer. So am I. So please tell me how an RBMK reactor core explodes. Not a meltdown, an explosion. I'd love to know.

- Sitnikov: I can't.

- Fomin: Are you stupid?

- Sitnikov: No.

- Fomin: Then why can't you?

- Sitnikov: I... [stammers] I don't see how it could explode. [Fomin looks satisfied] But it did.

- Dyatlov: [pounds the table, swaying on his feet] Enough! I'll go up to the vent block roof. From there, you can look right down into reactor building 4. I'll see it with my own... with my own eyes. [vomits on the table] I apologize. [collapses]

- [Meeting of the plant's executive committee]

- Zharkov: I wonder how many of you know the name of this place. We all call it "Chernobyl", of course. What is its real name?

- Viktor Bryukhanov: The Vladimir I. Lenin Nuclear Power Station.

- Zharkov: Exactly. Vladimir I. Lenin. [points to the image of Lenin on the nearby wall] And how proud he would be of you all tonight. Especially you, young man, the passion you have for the people. For is that not the sole purpose of the apparatus of the State? Sometimes we forget. Sometimes we fall prey to fear. But our faith in Soviet socialism will always be rewarded. Now the State tells us the situation here is not dangerous. Have faith, comrades. The State tells us it wants to prevent a panic. Listen well! It's true, when the people see the police, they will be afraid. But it is my experience that when the people ask questions that are not in their own best interest, they should simply be told to keep their minds on their labor and leave matters of the State to the State. We seal off the city. No one leaves. And cut the phone lines. Contain the spread of misinformation. That is how we keep the people from undermining the fruits of their own labor. Yes, comrades... we will all be rewarded for what we do here tonight. This is our moment to shine.

Please Remain Calm [2]

[edit]- [Dmitri wakes Ulana up at her lab, 7 hours after the explosion]

- Dmitri: You work too hard.

- Ulana Khomyuk: Where is everyone?

- Dmitri: Oh, they refused to come in.

- Ulana: Why?

- Dmitri: It's Saturday.

- Ulana: Why did you come in?

- Dmitri: I work too hard. It's boiling in here. [opens a window. A radiation alarm goes off. Dmitri immediately closes the window and then checks the alarm's reading.] Eight millirontgen. Leak?

- Ulana: No, it would've gone off before. It's coming from outside.

- Dmitri: The Americans?

- [Ulana grabs a swab, opens a window, gathers a sample of dust from the window's outside, then closes the window and takes the swab sample to a machine to get a reading. Returns with the reading]

- Ulana: Iodine-131. It's not military, it's uranium decay: U-235.

- Dmitri: Reactor fuel? [Ulana goes to a phone] Ignalina, maybe? 240 km away?

- Ulana: [calls the Ignalina power station] Yes, this is Ulana Khomyuk, with the Institute of Nuclear En...looking for...[listens to the person on the phone] Alright, stay calm- [gets interrupted by the other person on the line before getting hung up on] They're at 4. It's not them. Who's the next closest?

- Dmitri: Chernobyl, but that's not possible. They're 400 km away.

- Ulana: Well, then that's too far for 8 millirontgen. They'd have to be split open. Maybe they know something. [Calls Chernobyl, and takes a pill, passing the bottle to Dmitri] Iodine.

- Dmitri: Could it be a waste dump?

- Ulana: We'd be seeing other isotopes.

- Dmitri: Nuclear test? Uh, a new kind of bomb?

- Ulana: We'd have heard. That's what half of our people work on here.

- Dmitri: Something with the space program, like a satellite, or...

- Ulana: [looks at Dmitri with concern, referring to her call to Chernobyl] No one's answering the phone...

- [The Central Committee, Moscow: Valery Legasov enters the room with General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and Deputy Chairman Boris Shcherbina]

- Mikhail Gorbachev: Thank you all for your duty to this commission. We will begin with Deputy Chairman Shcherbina's briefing, and then we will discuss next steps if necessary.

- Boris Shcherbina: Thank you, Comrade General Secretary. I'm pleased to report that the situation in Chernobyl is stable. Military and civilian patrols have secured the region, and Colonel General Pikalov, who commands troops specializing in chemical hazards, has been dispatched to the plant. In terms of radiation, plant director Bryukhanov reports no more than 3.6 roentgen. I'm told it's the equivalent of a chest X-ray. So if you're overdue for a check-up...

- Gorbachev: And foreign press?

- Shcherbina: Totally unaware. KGB First Deputy Chairman Charkov assures me that we have successfully protected our security interests.

- Gorbachev: Good. Very good. Well, it seems like it's well in hand, so... if there's nothing else, meeting adjourned.

- [Gorbachev and the committee begins to stand up]

- Valery Legasov: [Pounds table] No!

- Gorbachev: Pardon me?

- Legasov: Uh, we can't adjourn.

- Shcherbina: This is Professor Legasov of the Kurchatov Institute. Professor, if you have any concerns, feel free to address them with me, later.

- Legasov: I can't. I am sorry. I'm so sorry. [Frantically flips through the pages of reports] Page three, the section on casualties. Uh...[reads the reports] "A fireman was severely burned on his hand by a chunk of smooth, black mineral on the ground, outside the reactor building." Smooth, black mineral—graphite. There's-There's graphite on the ground.

- Shcherbina: [To Gorbachev] Well, there was a—a tank explosion. There's debris. Of what importance that could be, I have n—

- Legasov: [Overlapping] There's only one place in the entire facility where you will find graphite: inside the core. If there's graphite on the ground outside, it means it wasn't a control system tank that exploded. It was the reactor core. It's open! [Inhales]

- Gorbachev: [Reads through the reports again] Um, Comrade Shcherbina?

- Shcherbina: Comrade General Secretary, I can assure you that Professor Legasov is mistaken. Bryukhanov reports that the reactor core is intact. And as for the radiation—

- Legasov: Yes, 3.6 roentgen, which, by the way, is not the equivalent of one chest X-ray, but rather 400 chest X-rays. That number's been bothering me for a different reason, though. It's also the maximum reading on low-limit dosimeters. They gave us the number they had. I think the true number is much, much higher. If I'm right, this fireman was holding the equivalent of four million chest X-rays in his hand.

- Shcherbina: Professor Legasov, there's no place for alarmist hysteria—

- Legasov: It's not alarmist if it's a fact!

- Gorbachev: Well, I don't hear any facts at all. All I hear is a man I don't know engaging in conjecture in direct contradiction to what has been reported by party officials.

- Legasov: [Stammers] I'm, uh, I apologize. I didn't mean, uh...[clears throat] Please, may I express my concern as—as calmly and as respectfully as I—

- Shcherbina: Professor Legasov—

- Gorbachev: [Interrupts] Boris. I will allow it.

- [Everyone sits right back down]

- Legasov: Um... An RBMK reactor uses Uranium-235 as fuel. Every atom of U-235 is like a bullet traveling at nearly the speed of light, penetrating everything in its path: woods, metal, concrete, flesh. Every gram of U-235 holds over a billion trillion of these bullets. That's in one gram. Now, Chernobyl holds over three million grams, and right now, it is on fire. Winds will carry radioactive particles across the entire continent, rain will bring them down on us. That's three million billion trillion bullets in the... in the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat. Most of these bullets will not stop firing for one hundred years. Some of them, not for fifty thousand years.

- [Beat.]

- Gorbachev: Yes, and, uh, this concern stems entirely from the description of a rock?

- Legasov: Yes.

- Gorbachev: Hmm. Comrade Shcherbina, I want you to go to Chernobyl. You take a look at the reactor—you, personally—and you report directly back to me.

- Shcherbina: A wise decision, Comrade General Secretary. I—

- Gorbachev: And take Professor Legasov with you.

- Shcherbina: Uh...[Chuckles] Forgive me, Comrade General Secretary, but I—

- Gorbachev: Do you know how a nuclear reactor works?

- Shcherbina: No.

- Gorbachev: No. Well, then how will you know what you're looking at? Meeting adjourned.

- [As Valery Legasov and Boris Shcherbina make their way to Chernobyl in a helicopter...]

- Boris Shcherbina: How does a nuclear reactor work?

- Valery Legasov: What?

- Shcherbina: It's a simple question.

- Legasov: It's hardly a simple answer.

- Shcherbina: Of course, you presume I'm too stupid to understand. So I'll restate: Tell me how a nuclear reactor works, or I'll have one of these soldiers throw you out of the helicopter.

- Legasov: A nuclear reactor makes electricity with steam. The steam turns a turbine which generates electricity. Where a typical power plant makes steam by burning coal, a nuclear plant...

- [Legasov tries to find a pen in his pocket to draw a diagram. Scherbina hands his pen and a scratch paper to Legasov]

- Legasov: [Draws diagram] In a nuclear plant, we use something called fission. We take an unstable element like Uranium-235, which has too many neutrons. A neutron is, uh—

- Shcherbina: The bullet.

- Legasov: [Impressed] Yes, the bullet. So, bullets are flying off of the uranium. Now...if we put enough uranium atoms close together, the bullets from one atom will eventually strike another atom. The force of this impact splits that atom apart, releasing a tremendous amount of energy, fission.

- Shcherbina: And the graphite?

- Legasov: [Exhales] Ah, yes. The neutrons are actually traveling so fast we call this "flux"—it's relatively unlikely that the uranium atoms will ever hit one another. In RBMK reactors, we surround the fuel rods with graphite to moderate—slow down—the neutron flux.

- Shcherbina: Good. [Takes his pen back] I know how a nuclear reactor works. Now I don't need you.

- [Legasov and Shcherbina's helicopter approaches the Chernobyl plant]

- Legasov: [Sees the reactor, horrified] What have they done?

- Shcherbina: Can you see inside?

- Legasov: I don't have to. Look. That's graphite on the roof. The whole building's been blown open. The core's exposed!

- Shcherbina: I can't see how you can tell that from here.

- Legasov: Oh, for God's sakes! Look at that glow! That's radiation ionizing the air!

- Shcherbina: Well, if we can't see, we don't know. [to the pilot] Get us directly over the building!

- Legasov: Boris, if we fly...

- Shcherbina: Don't you use my name!

- Legasov: ...directly over an open reactor...

- Shcherbina: I didn't ask your advice!

- Legasov: ...we'll be dead within a week! Dead!

- Pilot: Sir?

- Shcherbina: Get us over that building, or I'll have you shot!

- Legasov: [to the pilot] If you fly directly over that core, I promise you, by tomorrow morning, you'll be begging for that bullet! [the pilot considers this, and changes course]

- [Inside a military jeep, as Fomin and Bryukhanov prepare to meet Shcherbina...]

- Fomin: It's overkill. Pikalov's showing off to make us look bad.

- Bryukhanov: It doesn't matter how it looks. Shcherbina is a pure bureaucrat, as stupid as he is pigheaded. We'll tell him the truth in the simplest terms possible. We'll be fine. [Both exit the jeep] Pikalov!

- [Pikalov joins in with Fomin and Bryukhanov to welcome Shcherbina. Legasov is standing at a distance as Shcherbina, alone, is saluted by Pikalov]

- Bryukhanov: Comrade Shcherbina, Chief Engineer Fomin, Colonel General Pikalov, and I are honored at your arrival.

- Fomin: Deeply, deeply honored.

- Bryukhanov: Naturally, we regret the circumstances of your visit, but as you can see, we are making excellent progress in containing the damage. [Pulls out his notepad] We have begun our own inquiry into the cause of the accident, and I have a list of individuals who we believe are accountable.

- [Shcherbina reads through the note and gestures Legasov to join them]

- Bryukhanov: Professor Legasov, I understand you've been saying dangerous things.

- Fomin: Very dangerous things. Apparently, our reactor core exploded. Please, tell me how an RBMK reactor core explodes.

- Legasov: I'm not prepared to explain it at this time.

- Fomin: As I presumed, he has no answer.

- Bryukhanov: It's disgraceful, really. To spread disinformation at a time like this.

- [Legasov, in a tense situation, says nothing and looks to Shcherbina]

- Shcherbina: [Notices Legasov and turns to Bryukhanov] Why did I see graphite on the roof?

- [Bryukhanov and Fomin's smug expressions dissolve.]

- Shcherbina: Graphite is only found in the core, where it's used as a—neutron flux moderator. Correct?

- Bryukhanov: [beat] Fomin, why did the Deputy Chairman see graphite on the roof?

- Fomin: Well, that—that can't be. Comrade Shcherbina, my apologies, but graphite... that's not possible. Perhaps y—you saw burnt concrete.

- Shcherbina: Now there you made a mistake, because I may not know much about nuclear reactors, but I know a lot about concrete.

- Fomin: Comrade, I—I assure you—

- Shcherbina: I understand. [Points to Legasov] You think Legasov is wrong. How shall we prove it?

- Vladimir Pikalov: Our high-range dosimeter just arrived. We could cover one of our trucks with lead shielding, mount the dosimeter on the front.

- [all of them look at Legasov]

- Legasov: Have one of your men get as close to the fire as he can. Give him every bit of protection you have. But understand that even with lead shielding, it may not be enough.

- Pikalov: [grimly] Then I'll do it myself.

- Shcherbina: Good.

- [Colonel-General Pikalov returns from driving a high-level dosimeter close to the fire.]

- Pikalov: It's not three roentgen. It's fifteen thousand.

- [Legasov closes his eyes.]

- Bryukhanov: Comrade Shcherbina—

- [Scherbina just looks at him, and he shuts up instantly.]

- Shcherbina: [Turns to Legasov] What does that number mean?

- Legasov: It means the core is open. It means the fire we're watching with our own eyes is giving off nearly twice the radiation released by the bomb in Hiroshima. And that's every single hour. Hour after hour, [looks at his watch] 20 hours since the explosion, so forty bombs worth by now. Forty-eight more tomorrow. And it will not stop. Not in a week, not in a month. It will burn and spread its poison until the entire continent is dead.

- Shcherbina: [Turns to the soldiers] Please escort Comrades Bryukhanov and Fomin to the local party headquarters. [Turns to Bryukhanov] Thank you for your service.

- Bryukhanov: Comrade—

- Shcherbina: You're excused.

- Fomin: [As he's being taken away] Dyatlov was in charge. It was Dyatlov!

- Shcherbina: Tell me how to put it out.

- Pikalov: We'll use helicopters. We'll drop water on it like a forest fire—

- Legasov: No, no, no. You don't understand. This isn't a fire. This is a fissioning reactor core burning at over 2,000 degrees. The heat will instantly vaporize the water or worse—

- Shcherbina: How do we put it out?

- Legasov: [Sighs] You are dealing with something that has never occurred on this planet before. [Shcherbina begins to speak] Boron. Boron and sand. It'll create problems of its own, but I—I don't see any other way. Of course, it's going to take thousands of drops, because you can't fly the helicopters directly over the core, so most of it is going to miss.

- Shcherbina: How much sand and boron?

- Legasov: [Scoffs] Well, I can't be—

- Shcherbina: For God's sake, roughly!

- Legasov: Five thousand tons. And obviously, we're going to need to evacuate an enormous area—

- Shcherbina: Never mind that. Focus on the fire.

- Legasov: I am focusing on the fire. The wind, it's carrying all that smoke, all that radiation. At least evacuate Pripyat. It's three kilometers away.

- Shcherbina: That's my decision to make.

- Legasov: Then make it.

- Shcherbina: I've been told not to.

- Legasov: Is it or is not your decision—

- Shcherbina: I'm in charge here! This will go much easier if you talk to me about the things you do understand and not about the things you do not understand. [Walks back to the tent]

- Legasov: Where are you going?

- Shcherbina: I'm going to get you 5,000 tons of sand and boron.

- [Polissya hotel, Pripyat: Helicopters dropping sand and boron to extinguish the fire in the Chernobyl plant]

- Shcherbina: It's been smooth. Twenty drops. [notices Legasov's expression] What?

- Legasov: There are fifty thousand people in this city.

- Shcherbina: Professor Ilyin, who's also on the commission, says the radiation isn't high enough to evacuate.

- Legasov: Ilyin isn't a physicist.

- Shcherbina: Well, he's a medical doctor. If he says it's safe, it's safe.

- Legasov: Not if they stay here.

- Shcherbina: We're staying here.

- Legasov: [impatiently] Yes, we are, and we'll be dead in five years! [Shcherbina looks shocked] I'm sorry, I'm... I'm sorry.

- Shcherbina: [sits in stunned silence as the phone starts to ring; after several seconds, he answers it] Shcherbina. [listens] Thank you. [hangs up] A nuclear plant in Sweden has detected radiation and identified it as a byproduct of our fuel. The Americans took satellite photos. The reactor building, the smoke, the fire. The whole world knows. The wind has been blowing toward Germany. They're not letting children play outside... in Frankfurt. [glances outside at the children playing]

- [The Kremlin, Moscow: Legasov and Ulana Khomyuk explain the consequences of a nuclear meltdown with full water tanks]

- Ulana Khomyuk: When the lava enters these tanks, it will instantly superheat and vaporize approximately 7,000 cubic meters of water, causing a significant thermal explosion.

- Gorbachev: How significant?

- Khomyuk: We estimate between two and four megatons. Everything within a thirty-kilometer radius will be completely destroyed, including the three remaining reactors at Chernobyl. The entirety of the radioactive material in all of the cores will be ejected at force and dispersed by a massive shock wave, which will extend approximately two hundred kilometers and likely be fatal to the entire population of Kiev, as well as a portion of Minsk. The release of radiation will be severe, and will impact all of Soviet Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, Byelorussia, as well as Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and most of East Germany.

- Gorbachev: What do you mean, "impact"?

- Legasov: For much of the area, a nearly permanent disruption of the food and water supply, a steep increase in the rates of cancer and birth defects. I don't know how many deaths there will be, but many. For Byelorussia and the Ukraine, "impact" means completely uninhabitable for a minimum of one hundred years.

- Gorbachev: [visibly shaken] There are more than fifty million people living in Byelorussia and Ukraine.

- Legasov: Sixty, yes.

- Gorbachev: And how long before this happens?

- Legasov: Approximately 48 to 72 hours. But we may have a solution. We can pump the water from the tanks. Unfortunately, the tanks are sealed shut by a sluice gate, and the gate can only be opened manually from within the duct system itself. So we need to find three plant workers who know the facility well enough to enter the basement here, find their way through all these duct ways, get to the sluice gate valve here, and give us the access we need to pump out the tanks. Of course, we will need your permission.

- Gorbachev: My permission for what?

- Legasov: Um, the water in these tanks... the level of radioactive contamination --

- Khomyuk: They'll likely be dead in a week.

- Legasov: We're asking for your permission to... kill three men.

- [Tense silence.]

- Gorbachev: Well, Comrade Legasov... all victories inevitably come at a cost.

- [Legasov and Shcherbina faces incredulous workers as they ask for volunteers in a suicidal mission to open the sluice gate valve]

- Nuclear Worker: Now you want us to swim underneath a burning reactor. Do you even know how contaminated it is?

- Legasov: I... I don't have an exact number.

- Nuclear Worker: You don't need to have an exact number to know if it will kill us. But you can't even tell us that. Why should we do this? For what, for four hundred rubles?

- Shcherbina: You'll do it because it must be done. You'll do it because nobody else can. And if you don't, millions will die. If you tell me that's not enough I won't believe you. This is what has always set our people apart. A thousand years of sacrifice in our veins. And every generation must know its own suffering. I spit on the people who did this. And I curse the price that I have to pay. But I'm making my peace with it. Now you make yours. Go into that water. Because it must be done.

- [Silence.]

- Alexei Ananenko: [stands] Ananenko.

- Valeri Bespalov: [stands] Bespalov.

- Boris Baranov: [stands] Baranov.

Open Wide, O Earth [3]

[edit]- Shcherbina: What will happen to our boys?

- Legasov: Which boys? The divers?

- Shcherbina: The divers, the firefighters, the men in the control room. What does the radiation do to them precisely?

- Legasov: At the levels some of them were exposed? Ionizing radiation tears the cellular structure apart. The skin blisters, turns red, then black. This is followed by a latency period. The immediate effects subside. The patient appears to be recovering. Healthy, even. But they aren't. This usually only lasts for a day or two.

- Shcherbina: [beat] Continue.

- Legasov: Then the cellular damage begins to manifest. The bone marrow dies, the immune system fails, the organs and soft tissue begin to decompose. The arteries and veins spill open like sieves, to the point where you can't even administer morphine for the pain, which is… unimaginable. And then three days to three weeks, you are dead. That is what will happen to those boys.

- Shcherbina: And what about us?

- Legasov: Well, we've...We've gotten a steady dose, but not as much of it. Not strong enough to kill the cells, but consistent enough to damage our DNA. So, in time, cancer. Or aplastic anemia. Either way, fatal.

- Shcherbina: [beat] Well, in a sense, it would seem we've gotten off easy then, Valery.

- [May 3, 1986: A Party official and two soldiers arrive at a coal mine in Tula, Russian SFSR]

- Mikhail Shchadov: Who's in charge here?

- Andrei Glukhov: I'm the crew chief.

- Shchadov: I am Shchadov, minister of coal industries.

- Glukhov: We know who you are.

- Shchadov: How many men do you have?

- Glukhov: On this shift, 45 here, a hundred in total.

- Shchadov: I need all one hundred men to gather their equipment and get on the trucks.

- Glukhov: [smirking] Do you? To where?

- Shchadov: That's classified.

- Glukhov: Come on, then. Start shooting. You haven't got enough bullets for all of us. Kill as many as you can. Whoever's left, they'll beat the living piss out of each of you.

- Soldier: You can't talk to us like that!

- Glukhov: Shut the fuck up! This is Tula. This is our mine. We don't leave unless we know why.

- Shchadov: You're going to Chernobyl. Do you know what's happened there?

- Glukhov: [somewhat less confident] We dig up coal, not bodies.

- Shchadov: The reactor fuel is going to sink into the ground and poison the water from Kiev to the Black Sea. All of it. Forever, they say. They want you to stop that from happening.

- Glukhov: And how are we supposed to do that?

- Shchadov: They didn't tell me, because I don't need to know. Do you need to know, or have you heard enough?

- [Glukhov stares at him for a moment, then walks up and pats him on the shoulder with his sooty hands before walking to the trucks. The other miners do likewise, dirtying up his clean suit and his face]

- Miner: Now you look like the minister of coal.

- Shcherbina : Have you ever spent time with miners?

- Legasov: No.

- Shcherbina :My advice, tell the truth. These men work in the dark; they see everything.

- [After a meeting with the Central Committee, Legasov confronts KGB official Aleksandr Charkov about Khomyuk's arrest]

- Legasov: She was arrested by the KGB. You are the first deputy chairman of the KGB.

- Aleksandr Charkov: [amused] I am. That's why I don't have to bother with arresting people anymore.

- Legasov: But you are bothering with having us followed.

- Shcherbina: I think the deputy chairman is busy...

- Charkov: No no, it's perfectly understandable. Comrade, I know you've heard the stories about us. When I hear them, even I am shocked. But we are not what people say. Yes, people are following you. People are following those people. And you see them? [indicates two agents behind him] They follow me. The KGB is a circle of accountability. Nothing more.

- Legasov: You know the work we're doing here. You really don't trust us?

- Charkov: Of course I do. But you know the old Russian proverb: "Trust, but verify." And the Americans think that Ronald Reagan thought that up. Can you imagine? It was very nice speaking with you. [turns to walk away]

- Legasov: I need her.

- Charkov: [turns back] So you will be accountable for her? [Legasov nods] Then it's done.

- Legasov: Her name is --

- Charkov: I know who she is. Good day, Professor. [walks off; Legasov glances at Shcherbina]

- Shcherbina: No, that went surprisingly well. You came off like a naive idiot. And naive idiots are not a threat.

- Legasov: Are you alright?

- Khomyuk: They didn't hurt me. They let a pregnant woman in with -- oh, it doesn't matter. They were stupid. I was stupid. Dyatlov won't talk to me. Akimov, yes, Toptunov, yes, but... Valery, Akimov... his face was gone.

- Legasov: You want to stop?

- Khomyuk: Is that a choice I even have?

- Legasov: Do you think the fuel will actually melt through the concrete pad?

- Khomyuk: I don't know. A forty-percent chance, maybe.

- Legasov: I said fifty. [chuckles] Either way, the numbers mean the same thing: "Maybe". Maybe the core will melt through to the groundwater. Maybe the miners I've told to dig under the reactor will save millions of lives. Maybe I'm killing them for nothing. I don't want to do this anymore. I want to stop. But I can't. I don't think you have a choice any more than I do. I think, despite the stupidity, the lies, even this, you are compelled. The problem has been assigned, and you will stop at nothing until you find an answer. Because that is who you are.

- Khomyuk: A lunatic, then.

- Legasov: A scientist.

The Happiness of All Mankind [4]

[edit]- [An old woman milking a cow refuses to evacuate from a village near Chernobyl]

- Old Woman: You know how old I am?

- Soldier: I don't know. Old.

- Old Woman: I'm 82. I've lived here my whole life. Right here, that house, this place. What do I care about "safe"?

- Soldier: I have a job. Don't cause trouble.

- Old Woman: Trouble? You're not the first soldier to stand here with a gun. When I was 12, the Revolution came. Tsar's men, then Bolsheviks. Boys like you marching in lines. They told us to leave. No. Then there was Stalin and his famine, the Holodomor. My parents died. Two of my sisters died. They told the rest of us to leave. No. Then the Great War. German boys, Russian boys. More soldiers, more famine, more bodies. My brothers never came home. But I stayed, and I'm still here. After all that I have seen... so I should leave now, because of something I cannot see at all? No.

- Soldier: [takes the milk bucket and dumps it out; the others honk the horns of their trucks] It's time to go. [the old woman simply grabs the bucket and starts milking the cow again] Please stand up now. This is your last warning. [the old woman continues to milk the cow, until the soldier shoots it in the head] It's time to go. [the old woman simply sits there]

- Bacho: I have only two rules. One: Don't point this gun at me. That's easy, right? You can point it at this piece of shit [camera pans to Garo smoking a cigarette], I don't give a fuck -- never me. Two: If you hit an animal and it doesn't die, keep shooting until it does. Don't let them suffer. Or I'll kill you, understand? I mean it. I've killed a lot of people.

- Bacho: Look. This happens to everyone the first time. Normally when you kill a man. But for you a dog. So what? There's no shame in it. You remember your first time, Garo? My first time, Afghanistan. We were moving through a house and... suddenly a man was there and I shot him in the stomach. Yeah, that's a real war story. There are never any good stories like in movies - they're shit. A man was there, boom... stomach. I was so scared I didn't pull the trigger again for the rest of the day. I thought, 'Well, that's it, Bacho. You put a bullet in someone. You're not you anymore. You'll never be you again.' But then you wake up the next morning and you're still you. And you realize: that was you all along. You just didn't know.

- Legasov: [showing pictures of the damaged reactor] The atom is a humbling thing.

- General Nikolai Tarakanov: It's not humbling, it's humiliating. Why is the core still exposed to the air? Why have we not already covered it up?

- Legasov: We want to, but we can't get close enough. The debris on the roof is graphite from the core itself. Until we can push it off the roof back into the reactor, it'll kill anyone who gets near it. You see the roof is in three levels. We've named them. The small one here is Katya, one thousand roentgen per hour. Presume two hours of exposure is fatal. The one on the side, Nina, two thousand roentgen. One hour, fatal.

- Tarakanov: We used remote-controlled bulldozers in Afghanistan.

- Shcherbina: Too heavy. They'd fall right through.

- Tarakanov: So then...?

- Legasov: Moon rovers. Lunokhod STR-1s. They're light. And if we line them with lead, they can withstand the radiation.

- Shcherbina: We couldn't put a man on the Moon. At least we can keep a man off a roof.

- Legasov: That is the most important thing, General. Under no circumstances can men go up there. Robots only.

- Tarakanov: What about this large section here?

- Shcherbina: [grimly] Masha.

- Legasov: Twelve thousand roentgen. If you were to stand there in full protective gear head-to-toe for two minutes, your life expectancy would be cut in half. By three minutes, you're dead within months. Even our lunar rovers won't work on Masha. That amount of gamma radiation penetrates everything. The particles literally shred the circuits in microchips apart. If it's more complicated than a light switch, Masha will destroy it.

- Shcherbina: It would be fair to say that that piece of roof is the most dangerous place on Earth.

- Tarakanov: [sits in stunned silence for a moment, before taking a draw from his cigarette] So... what do we do?

- Shcherbina: That's what we wanted to ask you.

- [After a West German robot clearing graphite from the roof fails due to the radiation, Shcherbina is on the phone with Moscow, shouting furiously.]

- Shcherbina: Of course I know they're listening! I want them to hear! I want them to hear it all! [outside, Legasov and General Tarakanov can easily hear] Do you know what we're doing here?! Tell those geniuses what they have done! I don't give a fuck! Tell them! Go tell them! Ryzhkov! Go tell them he's a joke! Tell fucking Gorbachev! TELL THEM! [smashes the phone to pieces, then drags them outside before tossing them into the grass, then turns to Legasov and Tarakanov] The official position of the State is that a global nuclear catastrophe is not possible in the Soviet Union. They told the Germans that the highest detected level of radiation was two thousand roentgen. They gave them the propaganda number. That robot was never going to work. [to one of the guards] We need a new phone.

- [General Tarakanov briefs his men before sending them to clear roof level "Masha"]

- Tarakanov: Comrade soldiers, the Soviet people have had enough of this accident. They want us to clean this up, and we have entrusted you with this serious task. Because of the nature of the working area, you will each have no more than ninety seconds to solve this problem. Listen careful to each of my instructions, and do exactly as you have been told. This is for your own safety and the safety of your comrades. You will enter Reactor Building 3, climb the stairs, but do not immediately proceed to the roof. When you get to the top, wait inside behind the entrance to the roof, and catch your breath. You will need it for what comes next. [indicates photographs of the roof] This is the working area. We must clear the graphite. Some of it is in blocks weighing approximately 40 to 50 kilograms. They all must be thrown over the edge here. Watch your comrades moving fast from this opening, then turning to the left, then entering the workspace here. Take care not to stumble. There's a hole in the roof. Take care not to fall. You will need to move quickly, and you will need to move carefully. Do you understand your mission as I have described it?

- Soldiers: [in unison]: Yes, Comrade General!

- Tarakanov: These are the most important ninety seconds of your lives. Commit your task to memory, and do your job.

- Tarakanov: Congratulations comrades. You are the last of 3,828 men. You have performed your duties perfectly. I wish you all good health and long life. All of you are awarded a bonus of 800 rubles.

- [Tarakanov goes down a line of Soldiers, shaking hands with each individual]

- Tarakanov: Thank you.

- Soviet Soldier: I serve the Soviet Union.

- Tarakanov: Thank you.

- Soviet Soldier: I serve the Soviet Union.

- Tarakanov: Thank you.

- Soviet Soldier: I serve the Soviet Union.

Vichnaya Pamyat [5]

[edit]- [Pripyat, April 25, 1986 - twelve hours prior to the explosion]

- Fomin: I hear they might promote Bryukhanov. This little problem we have with the safety test, if it's completed successfully... yes, I think promotion's very likely. Who knows? Maybe Moscow. Naturally, they'll put me in charge once he's gone, and then I'll need someone to take my old job. I could pick Sitnikov.

- Dyatlov: I would like to be considered.

- Fomin: We'll keep that in mind. [Bryukhanov enters] Viktor Petrovich, preparations for the test have gone smoothly. Comrade Dyatlov's been working per my instructions, and reactor 4's output has been reduced to 1600 megawatts. With your approval, we're ready to continue lowering power to --

- Bryukhanov: We have to wait.

- Fomin: Is, uh...

- Bryukhanov: Are you going to ask me if there's a problem, Nikolai? You can't read a fucking face? Three years, I've tried to finish this test. Three years. [lights a cigarette] I've just had a call from the grid controller in Kiev. He says we can't lower power any further. Not for another ten hours.

- Dyatlov: A grid controller? Where does he get off telling us--

- Bryukhanov: It's not the grid controller's decision, Dyatlov. It's the end of the month. All the productivity quotas. Everyone's working overtime, the factories need power, someone's pushing down from above, not that we'll ever know who. [sighs] So do we have to scrap it, or what?

- Fomin: No, I don't think so. If we need to wait ten hours, we wait.

- Bryukhanov: [to Dyatlov] Running half power, not going to have stability issues?

- Fomin: No, I should think --

- Bryukhanov: I'm not asking you.

- Dyatlov: It's safe. We'll maintain at 1600. I'll go home, get some sleep, come back tonight. We'll proceed then. I'll personally supervise the test, and it will be completed.

- Bryukhanov: Well, I'm not waiting around. Call me when it's done.

- Khomyuk: I want you to think of Yuri Gagarin. I want you to imagine he had been told nothing of his mission into space until the moment he was on the launch pad. I want you to imagine all he had was a list of instructions he'd never seen before, with some of them crossed out. That is exactly what was happening in the control room of Reactor 4. The night shift had not been trained to perform the experiment. They hadn't even been warned it was happening. Leonid Toptunov, the operator responsible for controlling and stabilizing the reactor that night, was all of 25-years old. His total experience on the job? Four months. This was the human problem created by the delay. But inside the reactor core, something far more dangerous was forming. A poison. The time is 28 past midnight.

- [During the test at Chernobyl, the reactor stalls, but Dyatlov insists on continuing the test]

- Dyatlov: Raise the power.

- Akimov: No. I won't do it, it isn't safe.

- [Dyatlov stares at Akimov for a moment, then Toptunov, then back at Akimov]

- Dyatlov: Safety first, always. I've been saying that for 25 years. That's how long I've been doing this job, 25 years. Is that longer than you, Akimov?

- Akimov: Yes.

- Dyatlov: Is that much longer?

- Akimov: Yes.

- Dyatlov: [to Toptunov] And you, with your mother's tit barely out your mouth? [Toptunov is silent] See, if I say "it's safe", it's safe. And if the two of you disagree, then you don't have to work here. And you won't. But not just here. You won't work at Kursk, or Ignalina, or Leningrad, or Novovoronezh. You won't work anywhere ever again. I'll see to it. I think you know I will see to it. Raise the power.

- Akimov: [holds out the duty log] I would like you to record your command --

- Dyatlov: [slaps the log out of Akimov's hands] Raise the power.

- [Akimov picks up the log, then steps to the control console, as Dyatlov lights a cigarette behind him]

- Akimov: [to Toptunov] Together, then.

- [As the courtroom is at a recess, Legasov meets outside with Shcherbina, coughing into a handkerchief]

- Shcherbina: Do you know anything about this town, Chernobyl?

- Legasov: Not really, no.

- Shcherbina: It was mostly Jews and Poles. The Jews were killed in pogroms, and Stalin forced the Poles out. And then the Nazis came and killed whoever was left. But after the war, people came to live here anyway. They knew the ground under their feet was soaked in blood, but they didn't care. Dead Jews, dead Poles. But not them. No one ever thinks it's going to happen to them. And here we are.

- [Shcherbina shows Legasov his handkerchief, stained with his blood from radiation sickness]

- Legasov: How much time?

- Shcherbina: Maybe a year. They call it a...[coughs] They call it a "long illness". It doesn't seem very long to me. I know you told me, and I believed you. But time passed, and I thought, it wouldn't happen to me. I wasted it. I wasted it all for nothing.

- Legasov: For nothing?

- Shcherbina: Do you remember that morning when I first called you, how unconcerned I was? I don't believe much that comes out of the Kremlin, but when they told me they were putting me in charge of the cleanup, and they said it wasn't serious, I believed them. You know why?

- Legasov: Because they put you in charge.

- Shcherbina: [dejectedly] Yeah. I'm an inconsequential man, Valera. That's all I've ever been. I hoped that one day I would matter, but I didn't. [pats Legasov on the shoulder] I just stood next to people who did.

- Legasov: There are other scientists like me. Any one of them could have done what I did. But you... everything we asked for, everything we needed. Men, material, lunar rovers. Who else could have done these things? They heard me, but they listened to you. Of all the ministers, and all the deputies, entire congregation of obedient fools... they mistakenly sent the one good man. For godsakes, Boris... you were the one who mattered most.

- Shcherbina: [sees a small caterpillar on his lap and lets it crawl on his index finger] Ah, it's beautiful.

- Legasov: Dyatlov broke every rule we have, and pushed a reactor to the brink of destruction. He did these things believing there was a fail-safe. A-Z-5. A simple button to shut it all down. But in the circumstance he created, there wasn't. The shut-down system had a fatal flaw. At 1:23 and 40 seconds, Akimov engages AZ-5. The fully-withdrawn control rods begin moving back into the reactor. These rods are made of boron, which reduces reactivity. But not their tips. The tips are made of graphite, which accelerates reactivity.

- Judge: Why?

- Legasov: Why? For the same reason our reactors do not have containment buildings around them like those in the West. The same reason we don't use properly enriched fuel in our cores. The same reason we are the only nation that builds water-cooled graphite-moderated reactors with a positive void coefficient... It's cheaper.

- Legasov: No one in the room that night knew the shutdown button (AZ-5) could act as a detonator. They didn't know it, because it was kept from them.

- Kadnikov: Comrade Legasov, you're contradicting your own testimony in Vienna.

- Legasov: My testimony in Vienna was a lie. I lied to the world. I'm not the only one who kept this secret. There are many. We were following orders, from the KGB, from the Central Committee. And right now, there are 16 reactors in the Soviet Union with the same fatal flaw. Three of them are still running less than 20 kilometers away, at Chernobyl.

- Kadnikov: Professor Legasov, if you mean to suggest the Soviet State is somehow responsible for what happened, then I must warn you, you are treading on dangerous ground.

- Legasov: I've already trod on dangerous ground. We're on dangerous ground right now, because of our secrets and our lies. They're practically what define us. When the truth offends, we—we lie and lie until we can no longer remember it is even there. But it is...still there. Every lie we tell incurs a debt to the truth. Sooner or later, that debt is paid. That is how...an RBMK reactor core explodes: Lies.

- [Legasov is arrested by the KGB for refusing to toe the party line and is led to a private interrogation room]

- Charkov: [reads file] Valery Alexeyevich Legasov, son of Alexei Legasov, Head of Ideological Compliance, Central Committee. Do you know what your father did there?

- Legasov: Yes.

- Charkov: As a student, you had a leadership position in Komsomol. Communist Youth, correct?

- Legasov: You already know.

- Charkov: Answer the question.

- Legasov: Yes.

- Charkov: At the Kurchatov Institute, you were the Communist Party secretary. In that position, you limited the promotion of Jewish scientists.

- Legasov: [beat] ...Yes.

- Charkov: To curry favor with Kremlin officials. You're one of us, Legasov. I can do anything I want with you. But what I want the most is for you to know that I know. You're not brave. You're not heroic. You're just a dying man who forgot himself.

- Legasov: I know who I am, and I know what I've done. In a just world, I'd be shot for my lies, but not for this, not for the truth.

- Charkov: Scientists... and your idiot obsessions with reasons. When the bullet hits your skull, what will it matter why? [beat] No one's getting shot, Legasov. The whole world saw you in Vienna; it would be embarrassing to kill you now. And for what? Your testimony today will not be accepted by the State. It will not be disseminated in the press. It never happened. No... you will live, however long you have. But not as a scientist. Not anymore. You'll keep your title and your office, but no duties. No authority. No friends. No one will talk to you. No one will listen to you. Other men, lesser men, will receive credit for the things you have done. Your legacy is now their legacy; you will live long enough to see that. [beat] What role did Shcherbina play in this?

- Legasov: None. He didn't know what I was gonna say.

- Charkov: What role did Khomyuk play in this?

- Legasov: None. She didn't know either.

- Charkov: After all you've said and done today, it would be curious if you chose this moment to lie.

- Legasov: I would think a man of your experience would know a lie when he hears one.

- Charkov: [beat] You will not meet or communicate with either one of them ever again. You will not communicate with anyone about Chernobyl ever again. You will remain so immaterial to the world around you that when you finally do die, it will be exceedingly hard to know that you ever lived at all. [starts to exit]

- Legasov: What if I refuse?

- Charkov: [turns back to face Legasov] Why worry about something that isn't going to happen?

- Legasov: [scoffs] "Why worry about something that isn't going to happen?" Oh, that's perfect. They should put that on our money.

- [Ending scene: As Legasov is driven away from Chernobyl by the KGB, his voice on tape is heard]

- Legasov: To be a scientist is to be naive. We are so focused on our search for truth, we fail to consider how few actually want us to find it. But it is always there, whether we see it or not, whether we choose to or not. The truth doesn't care about our needs or wants. It doesn't care about our governments, our ideologies, our religions. It will lie in wait for all time. And this, at last, is the gift of Chernobyl. Where I once would fear the cost of truth, now I only ask: "What is the cost of lies?"

- Ending Text:

- Valery Legasov took his own life at the age of 51 on April 26, 1988, exactly two years after the explosion at Chernobyl. The audio tapes of Legasov's memoirs were circulated among the Soviet scientific community. His suicide made it impossible for them to be ignored. In the aftermath of his death, Soviet officials finally acknowledged the design flaws of the RBMK nuclear reactors. Those reactors were immediately retrofitted to prevent an accident like Chernobyl from happening again.

- Legasov was aided by dozens of scientists who worked tirelessly alongside him at Chernobyl. Some spoke out against the official account of events and were subject to denunciation, arrest and imprisonment. The character of Ulana Khomyuk was created to represent them all and to honor their dedication and service to truth and humanity.

- Boris Shcherbina died on August 22, 1990, four years and four months after he was sent to Chernobyl.

- For their roles in the Chernobyl disaster, Viktor Bryukhanov, Anatoly Dyatlov and Nikolai Fomin were sentenced to ten years hard labor. After his release, Nikolai Fomin returned to work...at a nuclear power plant in Kalinin, Russia. Anatoly Dyatlov died from radiation-related illness in 1995. He was 64.

- Valery Khodemchuk's body was never recovered. He is permanently entombed under Reactor 4. The firefighters' clothing still remains in the basement of Pripyat Hospital. It is dangerously radioactive to this day.

- Following the death of her husband and daughter, Lyudmilla Ignatenko suffered multiple strokes. Doctors told her she would never be able to bear a child. They were wrong. She lives with her son in Kiev.

- Of the people who watched from the railway bridge, it has been reported that none survived. It is now known as "The Bridge of Death".

- 400 miners worked around the clock for one month to prevent a total nuclear meltdown. It is estimated that at least 100 of them died before the age of 40.

- It has been widely reported that the three divers who drained the bubbler tanks died as a result of their heroic actions. In fact, all three survived after hospitalization. Two are still alive today.

- Over 600,000 people were conscripted to serve in the Exclusion Zone. Despite widespread accounts of sickness and death as a result of radiation, the Soviet government kept no official records of their fate.

- The contaminated region of Ukraine and Belarus, known as the Exclusion Zone, ultimately encompassed 2,600 square kilometers. Approximately 300,000 people were displaced from their homes. They were told this was temporary. It is still forbidden to return.

- Mikhail Gorbachev presided over the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. In 2006, he wrote, "The nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl... was perhaps the true cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union."

- In 2017, work was completed on the New Safe Confinement at Chernobyl at a cost of nearly two billion dollars. It is designed to last 100 years.

- Following the explosion, there was a dramatic spike in cancer rates across Ukraine and Belarus. The highest increase was among children.

- We will never know the actual human cost of Chernobyl. Most estimates range from 4,000 to 93,000 deaths. The official Soviet death toll, unchanged since 1987...is 31.

- In memory of all who suffered and sacrificed.

Cast

[edit]- Jared Harris - Valery Legasov

- Stellan Skarsgård - Boris Shcherbina

- Emily Watson - Ulana Khomyuk

- Paul Ritter - Anatoly Dyatlov

- Con O'Neill - Viktor Bryukhanov

- Adrian Rawlins - Nikolai Fomin

- David Dencik - Mikhail Gorbachev

- Alex Ferns - Andrei Glukhov

- Ralph Ineson - General Nikolai Tarakanov

External links

[edit]- Chernobyl quotes at the Internet Movie Database

- The official site

- Chernobyl quotes at Filmywisdom