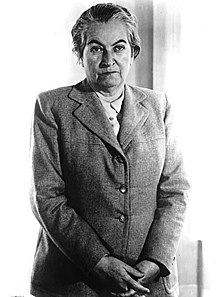

Gabriela Mistral

Lucila Godoy Alcayaga (Latin American Spanish: [luˈsila ɣoˈðoj alkaˈʝaɣa]; 7 April 1889 – 10 January 1957), known by her pseudonym Gabriela Mistral (Spanish: [ɡaˈβɾjela misˈtɾal]), was a Chilean poet-diplomat, educator, and Catholic. She was a member of the Secular Franciscan Order or Third Franciscan order. She was the first Latin American author to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature in 1945, "for her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world".

Quotes

[edit]- Ya en la mitad de mis días espigo

esta verdad con frescura de flor:

la vida es oro y dulzura de trigo,

es breve el odio e inmenso el amor.- Now in the middle of my days I glean

this truth that has a flower's freshness:

life is the gold and sweetness of wheat,

hate is brief and love immense. - Fragment from "Palabras Serenas"

- Now in the middle of my days I glean

- Piececitos de niño,

Dos joyitas sufrientes,

¡Cómo pasan sin veros

Las gentes!- Little feet of children,

two tiny suffering jewels,

how can people pass

and not see you! - Fragment from "Piececitos de Niño"

- Little feet of children,

"Message About the Jews" (1935)

[edit]Note in The House of Memory: Stories by Jewish Women Writers of Latin America edited by Marjorie Agosín (2022): "First published in El Mercurio, Santiago, Chile, June 16, 1935 and reprinted in 1987 in Prosa Religiosa de Gabriela Mistral, edited by Luis Vargas Saavedra, by Editorial Andrés Bello, Santiago, Chile. Translated from the Spanish by Alison Ridley."

- The German, Polish, or Lithuanian Jew has been deprived of the sacred right to escape and be free.

- It would be foolish for our America to latch onto the filthy tail of this antisemitic campaign. We have enough to do in our own nations-where everything is still in a state of primordial chemical soup-without distracting ourselves with French antics or absurd ventures in Berlin.

- At the very least we should not continue, in the manner of the Pharisees, using the ancient proclamation against the Jew who has been thoroughly undermined by us. Moreover, we should, at a minimum, desist from exclaiming in plazas or in our homes the rebuke that was heard in the Middle Ages: "Hunt? the Jewish dog for being an infidel." Jesus Christ, in his infinite nature, would surely be infinitely disgusted upon hearing us utter such words as his supposed advocates and the sentinels of his doctrine.

- Let's not ask our countries to accept a massive number of desolate Jewish immigrants. But let's do ask that they-with little rational effort, which is to say, with basic humanity-accept a small-agreed-upon quota of Jews who Europe has spewed from its twisted Christian viscera. Argentina has established-and I believe quite comfortably-its portion of the quota. If our twenty countries can follow through on this great act, which can only be termed an authentic act of decency, we will have accomplished an effective, honest, and generous feat. One should weigh and measure such adjectives carefully as they are very important to those who safeguard the continent's honor. By way of this act, we will have returned to Europe some of the culture and Christian policies that it originally imparted to us. In its stance toward the East, Europe has marred and debased its bimillenary rule. Let us cast back to Europe, from our side of the world, a collective gesture of an integral and inclusive Christian right that we learned from that continent during its purer era and that we have strengthened rather than squandered.

Quotes about

[edit]- One of the few Latin American intellectuals who stood up against fascism and spoke about the impending fate of European Jews was Gabriela Mistral, who, in 1945, became the only Latin American woman to date to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. While not a Jew herself, we include here one of her essays, "Message about the Jews,"-which she wrote in 1934, shortly before assuming her post as consul to Chile in Portugal-because it is a poignant testimony to her commitment to human rights and the Jewish people throughout historical times of great suffering when countless other prominent intellectuals chose silence. Mistral was also influential in assisting with Jewish emigration to Chile when, after 1939, most Latin American nations had closed their borders to desperate Jewish refugees seeking asylum.

- Marjorie Agosín Introduction to the second edition of The House of Memory: Stories by Jewish Women Writers of Latin America (2022)

- I think I am a bit like Mistral: always a foreigner, always from somewhere else.

- Marjorie Agosín Interview (2015)

- Chilean Gabriela Mistral who has been canonized as the Saint Mother…Mistral was an advocate for human rights and the plight of the Indian long before those concerns became fashionable.

- Marjorie Agosín Introduction to These Are Not Sweet Girls: Poetry by Latin American Women (2000), translated from Spanish by Monica Bruno

- The official image of Gabriela Mistral violates all cultural stereotypes since her poems to mothers, women and children are filled with a deep ideological content that goes beyond that of a teacher preoccupied with the future of her pupils. In the poems by Mistral included in this anthology, we get a glimpse of her powerful imagination and figurative language based on minute elements. Her poetry is often stripped of the traditional metaphors associated with the poetic language employed by the women of her time. Mistral's voice, depicted in melodious lullabies and fantastic stories

- Marjorie Agosín Introduction to These Are Not Sweet Girls: Poetry by Latin American Women (2000)

- Just a few years ago, one could easily identify the women in all of Latin America who stood out in literature. Names like Gabriela Mistral, Alfonsina Storni, Juana de Ibarború, Delmira Agustini, Claudia Lars, not to mention the greatest of them all, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz...

- Claribel Alegría speech (2006) Translation from the Spanish by David Draper Clark

- This was the kind of woman she was: attentive to the present, dominated by the conscience of her deeds and of the course that history takes, incapable of refusing the claims of those who suffer from hunger or thirst for justice and love...If we read her work carefully, we will find embodied there the same concepts and attitudes, and it would almost be impossible to distinguish between art and life or to say if there is more authentic poetry in her verses that in her acts...Everything she did, said, and wrote was in some way saturated with that poetic air, revealing the marvelous, if somewhat delicate balance between the ‘is’ and the ‘should be.'

- Margot Arce de Vazquez in Gabriela Mistral: The Poet and Her Work (1964), quoted here

- Mistral’s poetry is resolutely hermetic and often has a nightmarish quality. Even her nominally straightforward verses — those having to do with elements of nationalism, such as national symbology or national landscapes — contain a surreal quality...Mistral surrounded herself with and was surrounded by metaphors of silence, shame, and secrecy. Much of her poetic oeuvre revolves around a private world difficult to decipher, a world of loss and despair, of fantasy escapes into other realities.

- Licia Fiol-Matta, Introduction to A Queer Mother for the Nation: The State and Gabriela Mistral (2002)

- Gabriela Mistral of Chile, the only Latin American woman to have won the Nobel Prize, was an educator, pacifist, and humanist who wrote with matchless intensity of frustrated and suffering womanhood. Her children's songs and lullabies are among the tenderest in the Spanish language. Without children of her own, she turned her love of children into a universal love for all humanity. She became a kind of world mother, singing about children "as no one before her had ever done," said Paul Valéry. "While so many poets have exalted, celebrated, cursed or invoked death, or built, deepened, divinized the passion of love, few seem to have meditated on that transcendental act par excellence, the production of the living being by the living being.

- Angel Flores and Kate Flores, Introduction to The Defiant Muse: Hispanic Feminist Poems (1986)

- I translated Mistral because I discovered that she really has not been brought into English very much, Neruda over and over and over, but not Mistral. I fell in love with her. You have to fall in love, I think, to do a long translation. Yes, and then it's fun.

- from Conversations with Ursula Le Guin (2007)

- Poets—incredible nature poets like Mary Oliver, Gabriela Mistral, or Audre Lorde—look deeply at the world and make us feel like we are connected. Poetry that addresses the natural world helps us repair that connection. When you are paying attention to something, it’s a way of loving something. How can we continue to hurt something that we love?

- Some of the greatest Latin American poets have been women. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Gabriela Mistral, María Sabina, and Violeta Parra are among them, but their true place in the history of poetry has yet to be fully acknowledged...At the turn of the century, a legendary group of women poets emerged, including Delmira Agustini, Alfonsina Storni, and Gabriela Mistral. Their work caused scandal and outrage but ultimately opened the way for other women to explore their experience in a woman's voice...Mistral was the paradoxical mestiza, who embodied contradiction. A childless woman who exalted maternity, she simultaneously embraced and scorned her indianidad. Her extraordinary mix of biblical and Amerindian rhythms got her the Nobel Prize in 1945.

- Cecilia Vicuña The Oxford Book of Latin American Poetry (2009)

External links

[edit]- Gabriela Mistral Foundation

- Gabriela Mistral Poems

- List of Works

- Gabriela Mistral – University of Chile

- Gabriela Mistral (1889–1957) – Memoria Chilena

- Gabriela Mistral reads eighteen poems from her collected volumes: Ternura, Lagar, and Tala. Recorded at Library of Congress, Hispanic Division on 12 December 1950.