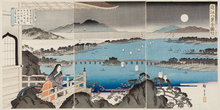

Murasaki Shikibu

Appearance

Murasaki Shikibu (紫 式部 Murasaki Shikibu, c. 973 or 978 – c. 1014 or 1031) was a novelist, poet, and servant of the imperial court during the Heian period of Japan. She is the author of the Tale of Genji.

| This article on an author is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |

Quotes

[edit]

- Seeing the water birds on the lake increase in number day by day, I thought to myself how nice it would be if it snowed before we got back to the Palace—the garden would look so beautiful; and then, two days later, while I was away on a short visit, lo and behold, it did snow. As I watched the rather drab scene at home, I felt both depressed and confused. For some years now I had existed from day to day in listless fashion, taking note of the flowers, the birds in song, the way the skies change from season to season, the moon, the frost and snow, doing little more than registering the passage of time. How would it all turn out? The thought of my continuing loneliness was unbearable, and yet I had managed to exchange sympathetic letters with those of like mind—some contacted via fairly tenuous connections—who would discuss my trifling tales and other matters with me; but I was merely amusing myself with fictions, finding solace for my idleness in foolish words. Aware of my own insignificance, I had at least managed for the time being to avoid anything that might have been considered shameful or unbecoming; yet here I was, tasting the bitterness of life to the very full.

- trans. Richard Bowring (Penguin Books, 1996)

- So all they see of me is a façade. There are times when I am forced to sit with them and on such occasions I simply ignore their petty criticisms, not because I am particularly shy but because I consider it pointless. As a result, they now look upon me as a dullard.

"Well, we never expected this!" they all say. "No one liked her. They all said she was pretentious, awkward, difficult to approach, prickly, too fond of her tales, haughty, prone to versifying, disdainful, cantankerous and scornful; but when you meet her, she is strangely meek, a completely different person altogether!"

How embarrassing! Do they really look upon me as such a dull thing, I wonder? But I am what I am. Her Majesty has also remarked more than once that she had thought I was not the kind of person with whom she could ever relax, but that I have now become closer to her than any of the others. I am so perverse and standoffish. If only I can avoid putting off those for whom I have a genuine regard.- trans. Richard Bowring

- To be pleasant, gentle, calm and self-possessed: this is the basis of good taste and charm in a woman. No matter how amorous or passionate you may be, as long as you are straightforward and refrain from causing others embarrassment, no one will mind. But women who are too vain and act pretentiously, to the extent that they make others feel uncomfortable, will themselves become the object of attention; and once that happens, people will find fault with whatever they say or do: whether it be how they enter a room, how they sit down, how they stand up or how they take their leave. Those who end up contradicting themselves and those who disparage their companions are also carefully watched and listened to all the more. As long as you are free from such faults, people will surely refrain from listening to tittle-tattle and will want to show you sympathy, if only for the sake of politeness. I am of the opinion that when you intentionally cause hurt to another, or indeed if you do ill through mere thoughtless behavior, you fully deserve to be censured in public. Some people are so good-natured that they can still care for those who despise them, but I myself find it very difficult. Did the Buddha himself in all his compassion ever preach that one should simply ignore those who slander the Three Treasures? How in this sullied world of ours can those who are hard done by be expected to reciprocate in kind?

- trans. Richard Bowring

- When my brother...was a young boy learning the Chinese classics, I was in the habit of listening with him and I became unusually proficient at understanding those passages that he found too difficult to grasp and memorize. Father, a most learned man, was always regretting the fact: "Just my luck!" he would say. "What a pity she was not born a man!" But then I gradually realized that people were saying "It's bad enough when a man flaunts his Chinese learning; she will come to no good," and since then I have avoided writing the simplest [Chinese] character. My handwriting is appalling.

- trans. Richard Bowring

- It is useless to talk with those who do not understand one and troublesome to talk with those who criticize from a feeling of superiority. Especially one-sided persons are troublesome. Few are accomplished in many arts and most cling narrowly to their own opinion.

- In Diaries of Court Ladies of Old Japan

- Sei Shōnagon is a smug and horrible person. She acts so smart and is always writing in true [Chinese] characters, but if you look closely, you can find lots of mistakes. People who try that hard to be different from everyone else always end up falling behind, with trouble waiting in their future; and people who are that affected act all mono no aware and attend all the interesting events even when they're lonely and bored, so that in the end the affectation stops being an act. How exactly are things going to end well for a person like that?

- (source)

- Unforgettably horrible is the naked body. It really does not have the slightest charm.

- Mono no aware.

- The sadness of things.

- Passim. Cf. Lacrimae rerum.

- Variant translations:

- The pathos of things.

- A sensitivity to things.

- The sorrow of human existence.

- I have finally realized how rarely you will find a flawless woman, one who is simply perfect. No doubt there are many who seem quite promising, write a flowing hand, give you back a perfectly acceptable poem, and all in all do credit enough to the rank they have to uphold, but you know, if you insist on any particular quality, you seldom find one who will do. Each one is all too pleased with her own accomplishments, runs others down, and so on. While a girl is under the eye of her adoring parents and living a sheltered life bright with future promise, it seems men have only to hear of some little talent of hers to be attracted. As long as she is pretty and innocent, and young enough to have nothing else on her mind, she may well put her heart into learning a pastime that she has seen others enjoy, and in fact she may become quite good at it. And when those who know her disguise her weaknesses and advertise whatever passable qualities she may have so as to present them in the best light, how could anyone think ill of her, having no reason to suspect her of being other than she seems? But when you look further to see whether it is all true, I am sure you can only end up disappointed.

- Spoken by Tō no Chūjō in Ch. 2: The Broom Tree (trans. Royall Tyler)

- "No art or learning is to be pursued halfheartedly," His Highness replied, "...and any art worth learning will certainly reward more or less generously the effort made to study it."

- Ch. 17: Eawase (trans. Royall Tyler)

The Tale of Genji, trans. Arthur Waley

[edit]

- Real things in the darkness seem no realer than dreams.

- Ch. 1: Kiritsubo

- Ceaseless as the interminable voices of the bell-cricket, all night till dawn my tears flow.

- Ch. 1

- It is in general the unexplored that attracts us.

- Ch. 9: Aoi

- Though the snow-drifts of Yoshino were heaped across his path, doubt not that whither his heart is set, his footsteps shall tread out their way.

- Ch. 19: A Wreath of Cloud

- Does it not move you strangely, the love-bird's cry, tonight when, like the drifting snow, memory piles up on memory?

- Ch. 20: Asagao

- [The art of the novel] does not simply consist in the author's telling a story about the adventures of some other person. On the contrary, it happens because the storyteller's own experience of men and things, whether for good or ill—not only what he has passed through himself, but even events which he has only witnessed or been told of—has moved him to an emotion so passionate that he can no longer keep it shut up in his heart.

- Ch. 25: The Glow-Worm

- Anything whatsoever may become the subject of a novel, provided only that it happens in this mundane life and not in some fairyland beyond our human ken.

- Ch. 25

- I have never thought there was much to be said in favor of dragging on long after all one's friends were dead.

- Ch. 29: The Royal Visit

- One ought not to be unkind to a woman merely on account of her plainness, any more than one had a right to take liberties with her merely because she was handsome.

- Ch. 36: Kashiwagi

- You that in far-off countries of the sky can dwell secure, look back upon me here; for I am weary of this frail world's decay.

- Ch. 40: The Law

- Think not that I have come in quest of common flowers; but rather to bemoan the loss of one whose scent has vanished from the air.

- Ch. 41: Mirage

Quotes about Murasaki

[edit]

~ Motoori Norinaga

- Heian Japan offers us some of the earliest examples of an attempt by women living in a male-dominated society to define the self in textual terms. Indeed, it is largely because of these works that classical Japanese becomes of more than parochial interest: as a result, the Heian period as a whole will always bear for us a strong female aspect. To a great extent it is the women who are the source of our historical knowledge: they have become our historians, and it is they who define the parameters within which we are permitted to approach their world and their men. In retrospect it is a form of sweet revenge.

- Richard Bowring, Murasaki Shikibu: The Tale of Genji (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 12

- There have been many interpretations over the years of the purpose of this tale. But all of these interpretations have been based not on a consideration of the novel itself but rather on the novel as seen from the point of view of Confucian and Buddhist works, and thus they do not represent the true purpose of the author. To seize upon an occasional similarity in sentiment or a chance correspondence in ideas with Confucian and Buddhist works, and proceed to generalize about the nature of the tale as a whole, is unwarranted. The general appeal of this tale is very different from that of such didactic works. Good and evil as found in this tale do not correspond to good and evil as found in Confucian and Buddhist writings. [...] Generally speaking, those who know the meaning of the sorrow of human existence, i.e., those who are in sympathy and in harmony with human sentiments, are regarded as good; and those who are not aware of the poignancy of human existence, i.e., those who are not in sympathy and not in harmony with human sentiments, are regarded as bad. [...] Since novels have as their object the teaching of the meaning of the nature of human existence, there are in their plots many points contrary to Confucian and Buddhist teachings. This is because among the varied feelings of man's reaction to things—whether good, bad, right, or wrong—there are feelings contrary to reason, however improper they may be. Man's feelings do not always follow the dictates of his mind. They arise in man in spite of himself and are difficult to control. In the instance of Prince Genji, his interest in and rendezvous with Utsusemi, Oborozukiyo, and the Consort Fujitsubo are acts of extraordinary iniquity and immorality according to the Confucian and Buddhist points of view. It would be difficult to call Prince Genji a good man, however numerous his other good qualities. But The Tale of Genji does not dwell on his iniquitous and immoral acts, but rather recites over and over again his awareness of the sorrow of existence, and represents him as a good man who combines in himself all good things in men.

- Motoori Norinaga, Genji Monogatari: Tama no Ogushi ("The Jeweled Comb of The Tale of Genji"), c. 1796

- The purpose of the Tale of Genji may be likened to the man who, loving the lotus flower, must collect and store muddy and foul water in order to plant and cultivate the flower. The impure mud of illicit love affairs described in the Tale is there not for the purpose of being admired but for the purpose of nurturing the flower of the awareness of the sorrow of human existence.

- Motoori Norinaga, in Tsunoda et al., eds., Sources of Japanese Tradition, Volume II (Columbia University Press, 1964), p. 29

- The Tale of Genji quite clearly breaks in two with Genji's death, but there is an earlier break, as Genji goes into his middle and late forties. If the book may thus be thought of as falling into three parts, the first part still has a great deal of the tenth century in it. The hero is an idealized prince, and, though there are setbacks, his early career is essentially a success story. [...] Then, some two-thirds of the way through the sections dominated by Genji, there comes a tidying up and packing away of things, as by someone getting ready to move on, and the matter of the last eight chapters before Genji's disappearance from the scene is rather different. Enough of romancing, Murasaki Shikibu seems to say, and one may imagine that she is leaving her own youth behind, the sad things are the real things. Shadows gather over Genji's life. The action is altogether less grand and more intimate, the characterization more subtle and compelling, than in the first section. Then, suddenly, Genji is dead. [...] Once more, and very boldly this time, Murasaki Shikibu has moved on. After the three transitional chapters come what are generally called the Uji chapters. The pessimism grows, the main action moves from the capital to the village of Uji, both character and action are more attenuated, and Murasaki Shikibu has a try, and many will say succeeds, at a most extraordinary thing, the creation of the first anti-hero in the literature of the world.

- Edward Seidensticker, Introduction (January 1976) to Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji (Penguin Books, 1981), pp. x–xi

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Murasaki Shikibu on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Murasaki Shikibu on Wikipedia Media related to Murasaki Shikibu on Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Murasaki Shikibu on Wikimedia Commons