Twilight of the Idols

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

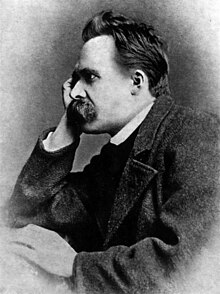

Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer (German: Götzen-Dämmerung, oder, Wie man mit dem Hammer philosophirt) is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche, written in 1888, and published in 1889.

Quotes

[edit]- ... imprisoned among all sorts of terrible concepts

- ‘You run ahead? Are you doing it as a shepherd? Or as an exception? A third case would be the fugitive. First question of conscience.’

- ‘Are you genuine? Or merely an actor? A representative? Or that which is represented? In the end, perhaps you are merely a copy of an actor. Second question of conscience.

- ‘Are you one who looks on? Or one who lends a hand? Or one who looks away and walks off? Third question of conscience.’

- ‘Do you want to walk along? Or walk ahead? Or walk by yourself? One must know what one wants and that one wants. Fourth question of conscience.’

- ‘Those were steps for me, and I have climbed up over them: to that end I had to pass over them. Yet they thought that I wanted to retire on them.’

- Auch der Muthigste von uns hat nur selten den Muth zu dem, was er eigentlich weiss.

- Even the most courageous among us only rarely has the courage to face what he already knows.

- “Maxims and Arrows,” 1.2

- Even the most courageous among us only rarely has the courage to face what he already knows.

- Die Weisheit zieht auch der Erkenntniss Grenzen.

- Wisdom sets bounds even to knowledge.

- “Maxims and Arrows,” § 1.5

- Wisdom sets bounds even to knowledge.

- I want, once and for all, not to know many things. Wisdom requires moderation in knowledge as in other things.

- “Maxims and Arrows,” § 1.5

- Daß man gegen seine Handlungen keine Feigheit begeht! daß man sie nicht hinterdrein im Stiche läßt!—Der Gewissensbiß ist unanständig.

- Not to perpetrate cowardice against one’s own acts! Not to leave them in the lurch afterward! The bite of conscience is indecent.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.10

- Not to perpetrate cowardice against one’s own acts! Not to leave them in the lurch afterward! The bite of conscience is indecent.

- Hat man sein warum? des Lebens, so verträgt man sich fast mit jedem wie?

- If we have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.12

- If we have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how.

- Ich mißtraue allen Systematikern und gehe ihnen aus dem Weg. Der Wille zum System ist ein Mangel an Rechtschaffenheit.

- I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.26

- I mistrust all systematizers and avoid them. The will to a system is a lack of integrity.

- Man begeht selten eine Übereilung allein. In der ersten Übereilung thut man immer zu viel. Eben darum begeht man gewöhnlich noch eine zweite—und nunmehr thut man zu wenig.

- One rarely falls into a single error. Falling into the first one, one always does too much. So one usually perpetrates another one—and now one does too little.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.30

- One rarely falls into a single error. Falling into the first one, one always does too much. So one usually perpetrates another one—and now one does too little.

- Es giebt einen Hass auf Lüge und Verstellung aus einem reizbaren Ehrbegriff; es giebt einen ebensolchen Hass aus Feigheit, insofern die Lüge, durch ein göttliches Gebot, verboten ist. Zu feige, um zu lügen.

- There is a hatred of lies; ... there is just as great a hatred of cowardice, insofar as the lie is prohibited by divine commandment. Too cowardly to lie.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.32

- There is a hatred of lies; ... there is just as great a hatred of cowardice, insofar as the lie is prohibited by divine commandment. Too cowardly to lie.

- Ohne Musik wäre das Leben ein Irrthum.

- Without music, life would be a mistake.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.33

- Without music, life would be a mistake.

- Nur die ergangenen Gedanken haben Werth.

- Only thoughts reached by walking have value.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.34

- Only thoughts reached by walking have value.

- Das waren Stufen für mich, ich bin über sie hinaufgestiegen,—dazu mußte ich über sie hinweg. Aber sie meinten, ich wollte mich auf ihnen zur Ruhe setzen.

- Those were steps for me, and I have climbed up over them... Yet they thought that I wanted to retire on them.

- “Maxims and Arrows” § 1.42

- Those were steps for me, and I have climbed up over them... Yet they thought that I wanted to retire on them.

- Der Fanatismus, mit dem sich das ganze griechische Nachdenken auf die Vernünftigkeit wirft, verräth eine Nothlage: man war in Gefahr, man hatte nur Eine Wahl: entweder zu Grunde zu gehn oder—absurd-vernünftig zu sein.

- The fanaticism with which all Greek reflection throws itself upon rationality betrays a desperate situation; there was danger, there was but one choice: either to perish or—to be absurdly rational.

- “The Problems of Socrates” § 2.10

- The fanaticism with which all Greek reflection throws itself upon rationality betrays a desperate situation; there was danger, there was but one choice: either to perish or—to be absurdly rational.

- All passions have a phase when they are merely disastrous, when they drag down their victim with the weight of stupidity—and a later, very much later phase when they wed the spirit, when they “spiritualize” themselves. Formerly, in view of the element of stupidity in passion, war was declared on passion itself, its destruction was plotted… The most famous formula for this is to be found in the New Testament.... There it is said, for example, with particular reference to sexuality: “If thy eye offend thee, pluck it out.” Fortunately, no Christian acts in accordance with this precept. Destroying the passions and cravings, merely as a preventive measure against their stupidity and the unpleasant consequences of this stupidity—today this itself strikes us as merely another acute form of stupidity. We no longer admire dentists who “pluck out” teeth so that they will not hurt any more.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.1

- The early church, as everyone knows, certainly did wage war against the intelligent.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.1 (Ludovici trans.)

- The church combats passion by means of excision of all kinds. Its practice, its remedy is castration. It never inquires, “How can a desire be spiritualized, beautified, deified.” In all ages it has laid the weight of discipline in the process of extirpation. The extirpation of sensuality, pride, lust of dominion, lust of property, and revenge. But to attack the passions at the roots means attacking life itself at its source. The method of the church is hostile to life.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.1 (Ludovici trans.)

- Castration and extirpation are instinctively chosen for waging war against a passion by those who are too weak of will, too degenerate, to impose some sort of moderation upon it.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.2 (Ludovici trans.)

- Radical and moral hostility to sensuality remains a suspicious symptom.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.2 (Ludovici trans.)

- The most poisonous diatribes against the senses have not been said by the impotent, nor by the ascetics, but by those impossible ascetics, by those who found it necessary to be ascetics.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.2 (Ludovici trans.)

- The spiritualization of sensuality is called love.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Ludovici trans.)

- …the value of having enemies …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Ludovici trans.)

- A man is productive only insofar as he is rich in contrasted instincts. He can remain young only on condition that his soul does not begin to take things easy and to yearn for peace.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 3 (Ludovici trans.)

- Nothing has grown more alien to us than that old desire, the peace of the soul, which is the aim of Christianity.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Ludovici trans.) 6:54

- … the well-being of unaccustomed satiety …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Ludovici trans.)

- … laziness, coaxed by vanity into togging itself out in a moral garb …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Ludovici trans.)

- The price of fruitfulness is to be rich in internal opposition …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.3 (Kaufmann trans)., p. 488

- Any one of the laws of life is fulfilled by the definite cannon “thou shalt.” “Thou shalt not,” and any sort of obstacle or hostile element in the road of life, is thus cleared away.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.4 (Ludovici trans.)

- The morality which is antagonistic to nature, that is to say, almost every morality that has been taught, honored and preached hitherto, is directed precisely against the life instincts. It is a condemnation, now secret, now blatant and impudent, of these very instincts.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.4 (Ludovici trans.)

- The saint in whom God is well pleased is the ideal Eunuch.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 4 (Ludovici trans.)

- Admitting that you have understood the villainy of such a mutiny against life as that which has become almost sacrosanct in Christian morality, you have fortunately understood something besides, and that is the futility, the fictitiousness, the absurdity and the falseness of such a mutiny. For the condemnation of life by a living creature is after all but the symptom of a definite kind of life.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.5 (Ludovici trans.)

- In order even to approach the problem of the value of life, a man would need to be placed outside life, and moreover know it as well as one, as many, as all in fact, who have lived it. These are reasons enough to prove to us that this problem is an inaccessible one to us.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.5 (Ludovici trans.)

- When we speak of values, we speak under the inspiration, and through the optics, of life. Life itself urges us to determine values. Life itself values through us when we determine values.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.5 (Ludovici trans.)

- Eine Verurteilung des Lebens von seiten des Lebenden bleibt zuletzt doch nur das Symptom einer bestimmten Art von Leben: die Frage, ob mit Recht, ob mit Unrecht, ist gar nicht damit aufgeworfen. Man müßte eine Stellung außerhalb des Lebens haben, und andrerseits es so gut kennen, wie einer, wie viele, wie alle, die es gelebt haben, um das Problem vom Wert des Lebens überhaupt anrühren zu dürfen: Gründe genug, um zu begreifen, daß dies Problem ein für uns unzugängliches Problem ist. Wenn wir von Werten reden, reden wir unter der Inspiration,

- A condemnation of life by the living remains in the end a mere symptom of a certain kind of life: the question whether it is justified or unjustified is not even raised thereby. One would require a position outside of life … in order to be permitted even to touch the problem of the value of life…

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.5 Kaufmann, trans., p. 490

- A condemnation of life by the living remains in the end a mere symptom of a certain kind of life: the question whether it is justified or unjustified is not even raised thereby. One would require a position outside of life … in order to be permitted even to touch the problem of the value of life…

- Morality as it has been understood hitherto … is the instinct of degeneration itself, which converts itself into an imperative. It says “perish.” It is the death sentence of men …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.5 (Ludovici trans.)

- Every healthy morality is dominated by an instinct of life… Anti-natural morality—that is, almost every morality which has so far been taught, revered and preached—turns, conversely, against the instincts of life: it is a condemnation of these instincts…

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5 Kaufmann, trans., p. 490

- Morality, insofar as it condemns for its own sake, and not out of regard for the concerns, considerations, and contrivances of life, is a specific error for which one ought to have no pity…

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5 Kaufmann, trans., p. 491

- Let us at last consider how exceedingly simple it is on our part to say: “Man should be thus and thus!” Reality shows us a marvelous wealth of types, and a luxuriant variety of forms and changes—and yet the first wretch of a moral loafer that comes along cries: “No! Man should be different.” He even knows what man should be like, this sanctimonious prig: he draws his own face on the wall and declares, “Ecce homo!”

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.6 (Ludovici trans.) 13:03

- The individual in his past and future is a piece of fate. One law the more, one necessity the more for all that is to come and is to be. To say to him, “change thyself” is tantamount to saying that everything should change, even backwards as well.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.6 (Ludovici trans.)

- Morality, insofar as it condemns per se, and not out of any aim, consideration or motive of life, is a specific error for which no one should feel any mercy—a degenerate idiosyncrasy that has done an unalterable amount of harm.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.6 (Ludovici trans.)

- We others, we immoralists, on the contrary, have opened our hearts wide to all kinds of comprehension, understanding, and approbation. We do not deny readily; we glory in saying “Yea” to things. Our eyes have opened ever wider and wider to that economy which still employs, and knows how to use to its own advantage, all that which the sacred craziness of priests and the morbid reason in priests rejects.

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.6 (Ludovici trans.)

- … the repulsive race of bigots, the priests and the virtuous …

- “Morality as Anti-Nature” § 5.6 (Ludovici trans.)

- Alles Gute ist Instinkt—und, folglich, leicht, nothwendig, frei. Die Mühsal ist ein Einwand.

- All that is good is instinct, and hence easy, necessary, free. Laboriousness is an objection.

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.2

- All that is good is instinct, and hence easy, necessary, free. Laboriousness is an objection.

- Die leichten Füsse das erste Attribut der Göttlichkeit.

- Light feet, the first attribute of divinity.

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.2

- Light feet, the first attribute of divinity.

- The so-called motive: another error. Merely a surface phenomenon of consciousness, something alongside the deed that is more likely to cover up the antecedents of the deeds than to represent them.

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.3

- And what a fine abuse we had perpetrated with this “empirical evidence”; we created the world on this basis as a world of causes, a world of will, a world of spirits. The most ancient and enduring psychology was at work here and did not do anything else: all that happened was considered a doing, all doing the effect of a will; the world became to it a multiplicity of doers; a doer (a “subject”) was slipped under all that happened. It was out of himself that man projected his three “inner facts”—that in which he believed most firmly: the will, the spirit, the ego. He even took the concept of being from the concept of the ego; he posited “things” as being, in his image, in accordance with his concept of the ego as a cause. Is it any wonder that later he always found in things only that which he had put into them?

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.3

- With the unknown, one is confronted with danger, discomfort, and care,—the first instinct is to abolish [wegzuschaffen] these painful states. First principle: any explanation is better than none. Since at bottom it is merely a matter of wishing to be rid of oppressive representations, one is not too particular about the means of getting rid of them: the first representation that explains the unknown as familiar feels so good that one “considers it true.” The proof of pleasure (“of strength”) as a criterion of truth. .— The causal instinct is thus conditional upon, and excited by, the feeling of fear. The “why?” shall, if at all possible, not give the cause for its own sake so much as for a kind of cause—a cause that is comforting, liberating, and relieving. That it is something already familiar, experienced, and inscribed in the memory, which is posited as a cause, that is the first consequence of this need. That which is new and strange and has not been experienced before, is excluded as a cause.— Thus one searches not only for some kind of explanation to serve as a cause, but for a selected and preferred kind of explanation—that which has most quickly and most frequently abolished the feeling of the strange, new, and hitherto unexperienced: the most habitual explanations.— Consequence: one kind of positing of causes predominates more and more, is concentrated into a system and finally emerges as dominant, that is, as simply precluding other causes and explanations.— The banker immediately thinks of “business,” the Christian of “sin,” and the girl of her love.

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.5

- The “explanation” of agreeable general feelings. They are produced by trust in God. They are produced by the consciousness of good deeds .. They are produced by faith, charity, and hope—the Christian virtues.— In truth, all these supposed explanations are resultant states and, as it were, translations of pleasurable or unpleasurable feelings into a false dialect: one is in a state of hope because the basic physiological feeling is once again strong and rich; one trusts in God because the feeling of fullness and strength gives a sense of rest.— Morality and religion belong altogether to the psychology of error: in every single case, cause and effect are confused; or truth is confused with the effects of believing something to be true; or a state of consciousness is confused with its causes.

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.6

- The error of free will.— Today we no longer have any pity for the concept of “free will”: we know only too well what it is—the foulest of all theologians’ artifices aimed at making mankind “responsible” in their sense, that is, dependent upon them ... Here I simply supply the psychology of all making-responsible.— Wherever responsibilities are sought, it is usually the instinct of wanting to judge and punish which is at work. Becoming has been deprived of its innocence when any being-such-and-such is traced back to will, to purposes, to acts of responsibility: the doctrine of the will has been invented essentially for the purpose of punishment, that is, because one wanted to impute guilt. The entire old psychology, the psychology of will, was conditioned by the fact that its originators, the priests at the head of ancient communities, wanted to create for themselves the right to punish—or wanted to create this right for God ... Men were considered “free” so that they might be judged and punished—so that they might become guilty: consequently, every act had to be considered as willed, and the origin of every act had to be considered as lying within the consciousness (—and thus the most fundamental counterfeit in psychologicis was made the principle of psychology itself ...). Today, as we have entered into the reverse movement and we immoralists are trying with all our strength to take the concept of guilt and the concept of punishment out of the world again, and to cleanse psychology, history, nature, and social institutions and sanctions of them, there is in our eyes no more radical opposition than that of the theologians, who continue with the concept of a “moral world-order” to infect the innocence of becoming by means of “punishment” and “guilt.” Christianity is a metaphysics of the hangman ...

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.7

- Moral judgment has this in common with the religious one: that it believes in realities which are not real.

- “The ‘Improvers’ of Mankind’” § 7.1

- Moral judgments, like religious ones, belong to a stage of ignorance at which the very concept of the real, and the distinction between what is real and imaginary, are still lacking.

- “The ‘Improvers’ of Mankind’” § 7.1

- Weder Manu, noch Plato, noch Confucius, noch die jüdischen und christlichen Lehrer haben je an ihrem Recht zur Lüge gezweifelt.

- Neither Manu nor Plato nor Confucius nor the Jewish and Christian teachers have ever doubted their right to lie.

- “The ‘improvers’ of mankind,” § 7.5

- Neither Manu nor Plato nor Confucius nor the Jewish and Christian teachers have ever doubted their right to lie.

- Alle Mittel, wodurch bisher die Menschheit moralisch gemacht werden sollte, waren von Grund aus unmoralisch.

- All the means by which one has so far attempted to make mankind moral were through and through immoral.

- “The ‘improvers’ of mankind,” § 7.5

- All the means by which one has so far attempted to make mankind moral were through and through immoral.

- Plato … says … that there would be no Platonic philosophy at all if there were not such beautiful youths in Athens.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.23

- Wenn man den christlichen Glauben aufgiebt, zieht man sich damit das Recht zur christlichen Moral unter den Füßen weg.

- When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.5 “George Eliot” p. 515

- When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet.

- Wenn thatsächlich die Engländer glauben, sie wüßten von sich aus, „intuitiv”, was gut und böse ist, wenn sie folglich vermeinen, das Christenthum als Garantie der Moral nicht mehr nöthig zu haben, so ist dies selbst bloß die Folge der Herrschaft des christlichen Werthurtheils und ein Ausdruck von der Stärke und Tiefe diesen Herrschaft: sodaß der Ursprung der englischen Moral vergessen worden ist, sodaß das Sehr-Bedingte ihres Rechts auf Dasein nicht mehr empfunden wird.

- When the English actually believe that they know “intuitively” what is good and evil, when they therefore suppose that they no longer require Christianity as the guarantee of morality, we merely witness the effects of the dominion of the Christian value judgment and an expression of the strength and depth of this dominion: such that the origin of English morality has been forgotten, such that the very conditional character of its right to existence is no longer felt. For the English, morality is not yet a problem.

- W. Kaufmann, trans. (1976), “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.5 “George Eliot” p. 516

- When the English actually believe that they know “intuitively” what is good and evil, when they therefore suppose that they no longer require Christianity as the guarantee of morality, we merely witness the effects of the dominion of the Christian value judgment and an expression of the strength and depth of this dominion: such that the origin of English morality has been forgotten, such that the very conditional character of its right to existence is no longer felt. For the English, morality is not yet a problem.

- In art, man enjoys himself as perfection.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.9

- The other thing I do not like to hear is the notorious “and” …

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.16

- How does one compromise oneself today? If one is consistent. If one proceeds in a straight line. If one is not ambiguous enough to permit five conflicting interpretations. If one is genuine.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.18 “On the ‘Intellectual Conscience’”

- Plato goes further. He says with an innocence possible only for a Greek, not a “Christian,” that there would be no Platonic philosophy at all if there were not such beautiful youths in Athens: it is only their sight that transposes the philosopher’s soul into an erotic trance, leaving it no peace until it lowers the seed of all exalted things into such beautiful soil.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.23

- “What is the task of all higher education?” To turn men into machines. “What are the means?” Man must learn to be bored. “How is that accomplished?” “By means of the concept of duty.”

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.29

- Nothing is more distasteful to true philosophers than man when he beings to wish. If they see man only at his deeds, if they see this bravest, craftiest, and most enduring of animals, even inextricably entangled in disaster, how admirable he then appears to them. They even encourage him. But true philosophers despise the man who wishes, as also the desirable man, and all the desiderata and ideals of man in general … he finds only nonentity behind human ideals, or, not even nonentity but vileness, absurdity, sickness, cowardice, fatigue, … How is it that man, who as a reality is so estimable, ceases from deserving respect the moment he begins to desire. Must he pay for being so perfect as a reality? Must he make up for his deeds, for the tension of spirit and will which underlies all his deeds, by an eclipse of his power in matters of the imagination, and in absurdity. … That which justifies man is his reality. It will justify him to all eternity. How much more valuable is a real man than any other man who is merely the phantom desires, of dreams …than any kind of ideal man.

- “Skirmishes in a War with the Age” § 9.32 (Ludovici trans.)

- Self-interest is worth as much as the person who has it.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.33 p. 533

- The single one, the “individual,” as hitherto understood by the people and the philosophers alike, is an error after all: he is nothing by himself, no atom, no “link in the chain,” nothing merely inherited from former times; he is the whole single line of humanity up to himself.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.33

- The way that the “single one” or the “individual,” has been hitherto understood, by the people and the philosophers alike, is an error. He is not a thing by himself, not an atom, not a “link in the chain,” not a thing merely inherited from former times. He represents the whole single line of humanity up to himself.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.33 (My rewording)

- The anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the declining strata of society, demands with a fine indignation what is “right,” “justice,” and “equal rights,” … the “fine indignation” itself soothes him; it is a pleasure for all wretched devils to scold: it gives a slight but intoxicating sense of power. Even plaintiveness and complaining can give life a charm.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.34

- Complaining is never any good: it stems from weakness. Whether one charges one’s misfortune to others or to oneself—the socialist does the former; the Christian, for example, the latter—really makes no difference. The common and, let us add, the unworthy thing is that it is supposed to be somebody’s fault that one is suffering; in short, that the sufferer prescribes the honey of revenge for himself against his suffering. The objects of this need for revenge, as a need for pleasure, are mere occasions: everywhere the sufferer finds occasions for satisfying his little revenge.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.34

- When the anarchist, as the mouthpiece of the decaying strata of society, raises his voice in splendid indignation for “right,” “justice,” “equal rights,” he is only groaning under the burden of his ignorance, which cannot understand why he actually suffers, what his poverty consists of: the poverty of life. An instinct of causality is active in him. Someone must be responsible for him being so ill at ease. His splendid indignation alone relieves him somewhat. It is a pleasure for all poor devils to grumble. It gives them a little intoxicating sensation of power. The very act of complaining, the mere fact that one bewails one’s lot, may lend such a charm to life that on that account alone one is ready to endure it. There is a small dose of revenge in every lamentation. One casts one’s affections, and, under certain circumstances, even one’s baseness, in the teeth of those who are different, as if their condition were an injustice and iniquitous privilege.

- “Skirmishes in a War with the Age” § 9.34 (Ludovici trans.)

- To bewail one’s lot is always despicable: it is always the outcome of weakness. Whether one ascribes one’s afflictions to others or to one’s self, it is all the same. The socialist does the former, the Christian, for instance, does the latter. That which is common to both attitudes, or rather that which is equally ignoble in them both, is the fact that somebody must be to blame if one suffers—in short, that the sufferer drugs himself with the honey of revenge to allay his anguish.

- “Skirmishes in a War with the Age” § 9.34 (Ludovici trans.)

- Instinctively to choose what is harmful for oneself, to feel attracted by “disinterested” motives, that is virtually the formula of decadence. “Not to seek one’s own advantage”—that is merely the moral fig leaf for quite a different, namely, a physiological, state of affairs: “I no longer know how to find my own advantage.” Disintegration of the instincts!

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.35

- Instead of saying naively, “I am no longer worth anything,” the moral lie in the mouth of the decadent says, “Nothing is worth anything, life is not worth anything.”

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.35

- Finally, some advice for our dear pessimists and other decadents. It is not in our hands to prevent our birth; but we can correct this mistake …one must advance a step further in its logic and not only negate life with “will and representation,” as Schopenhauer did—one must first of all negate Schopenhauer.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.36

- If one wants an end, one must also want the means: if one wants slaves, then one is a fool if one educates them to be masters.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.40

- Philosophers are merely another kind of saint, and their whole craft is such that they admit only certain truths—namely, those for the sake of which their craft is accorded public sanction.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.42 p. 546

- The criminal type is the type of the strong human being under unfavorable circumstances: a strong human being made sick.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.45

- Whoever must do secretly, with long suspense, caution, and cunning, what he can do best and would like most to do, becomes anemic; and because he always harvests only danger, persecution, and calamity from his instincts, his attitude to these instincts is reversed too

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.45

- It is society, our tame, mediocre, emasculated society, in which a natural human being … necessarily degenerates into a criminal.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.45 p. 549

- Let us generalize the case of the criminal: let us think of men so constituted that for one reason or another, they lack public approval and know that they are not felt to be beneficent or useful—that chandala feeling that one is not considered equal, but an outcast, unworthy, contaminating. All men so constituted have a subterranean hue to their thoughts and actions; everything about them becomes paler than in those whose existence is touched by daylight. Yet almost all forms of existence which we consider distinguished today once lived in this half tomblike atmosphere: the scientific character, the artist, the genius, the free spirit, the actor, the merchant, the great discoverer. … All innovators of the spirit must for a time bear the pallid and fatal mark of the chandala on their foreheads—not because they are considered that way by others, but because they themselves feel the terrible chasm which separates them from everything that is customary or reputable. Almost every genius knows, as one stage of his development, the “Catilinarian existence”—a feeling of hatred, revenge, and rebellion against everything which already is, which no longer becomes ... Catiline—the form of pre-existence of every Caesar.—

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.45

- In Athens, in the time of Cicero (who expresses his surprise about this), the men and youths were far superior in beauty to the women. But what work and exertion in the service of beauty had the male sex there imposed on itself for centuries!— For one should make no mistake about the method in this case: a breeding of feelings and thoughts alone is almost nothing (—this is the great misunderstanding underlying German education, which is wholly illusory): one must first persuade the body.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47

- Strict perseverance in significant and exquisite gestures together with the obligation to live only with people who do not “let themselves go”—that is quite enough for one to become significant and exquisite…

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47 p. 552

- Supreme rule of conduct: before oneself too, one must not “let oneself go.”

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47

- It is decisive for the lot of a people and of humanity that culture should begin in the right place—not in the “soul” (as was the fateful superstition of the priests and half-priests): the right place is the body, the gesture, the diet, physiology; the rest follows from that ... Therefore the Greeks remain the first cultural event in history—they knew, they did, what was needed; and Christianity, which despised the body, has been the greatest misfortune of humanity so far.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47

- The beauty of a race or family, their grace and graciousness in all gestures, is won by work: like genius, it is the end result of the accumulated work of generations. One must have made great sacrifices to good taste… one must have preferred beauty to advantage, habit, opinion and inertia.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47 “Beauty no accident” p. 551

- It is decisive … for humanity that culture should begin in the right place—not in the “soul”: … the right place is the body, the gesture, the diet, physiology; the rest follows from that. Therefore the Greeks remain the first cultural event in history: the knew, they did, what was needed; and Christianity, which despised the body, has been the greatest misfortune to humanity so far.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.47 p. 552

- Plato is a coward before reality, consequently he flees into the ideal

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.2

- [I praise] the unconditional will to not deceive oneself and to see reason in reality—not in “reason,” still less in “morality.”

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.2

- I know no higher symbolism than this Greek symbolism of the Dionysian festivals. Here the most profound instinct of life, that directed toward the future of life, the eternity of life, is experienced religiously—and the way to life, procreation, as the holy way. It was Christianity, with its ressentiment against life at the bottom of its heart, which first made something unclean of sexuality: it threw filth on the origin, on the presupposition of our life.

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.4

- For the Greeks the sexual symbol was therefore the venerable symbol par excellence, the real profundity in the whole of ancient piety. Every single element in the act of procreation, of pregnancy, and of birth aroused the highest and most solemn feelings.

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.4

- All becoming and growing—all that guarantees a future—involves pain.

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.4

- Saying Yes to life even in its strangest and hardest problems, the will to life rejoicing over its own inexhaustibility even in the very sacrifice of its highest types—that is what I called Dionysian.

- “What I owe to the ancients” § 10.5

- It is my ambition to say in ten sentences what everyone else says in a book.

- “Skirmishes of an untimely man” § 9.51

- The criminal type is the strong type under unfavorable conditions, a strong man rendered sickly. What he lacks is the jungle, a certain freer and more dangerous form of nature and existence where all that serves as arms and armor—in the strong man’s instinctive view—is his by right. His virtues society has prohibited; the liveliest impulses he has borne within him are quickly entangled with the crushing emotions of suspicion, fear and ignominy.

- § 9.45

- Was kann allein unsre Lehre sein?—Daß niemand dem Menschen seine Eigenschaften giebt, weder Gott, noch die Gesellschaft, noch seine Eltern und Vorfahren, noch er selbst ... Niemand ist dafür verantwortlich, daß er überhaupt da ist, daß er so und so beschaffen ist, daß er unter diesen Umständen in dieser Umgebung ist. Die Fatalität seines Wesens ist nicht herauszulösen aus der Fatalität alles dessen, was war und sein wird ... Man ist notwendig, man ist ein Stück Verhängnis, man gehört zum Ganzen, man ist im Ganzen,—es gibt nichts, was unser Sein richten, messen, vergleichen, verurteilen könnte, denn das hieße, das Ganze richten, messen, vergleichen, verurteilen ... Aber es gibt nichts außer dem Ganzen! . . .—Damit erst ist die Unschuld des Werdens wieder hergestellt

- Nobody gives man his attributes, neither God nor society nor his parents and forefathers, nor he himself ... Nobody is responsible for his being here at all, his disposition to this and that, his existing in these surroundings under these conditions. The fatality of his essential being is not to be puzzled out of the fatality of all that was and will be ... We are necessary, a portion of destiny, we belong to the whole, we are in the whole—and there is nothing which could judge, measure, compare and condemn our being, for that would mean judging, measuring, comparing and condemning the whole ... But there is nothing outside the whole! ... Only then is the innocence of becoming restored

- “The Four Great Errors” § 6.8 = KSA 6.96

- Nobody gives man his attributes, neither God nor society nor his parents and forefathers, nor he himself ... Nobody is responsible for his being here at all, his disposition to this and that, his existing in these surroundings under these conditions. The fatality of his essential being is not to be puzzled out of the fatality of all that was and will be ... We are necessary, a portion of destiny, we belong to the whole, we are in the whole—and there is nothing which could judge, measure, compare and condemn our being, for that would mean judging, measuring, comparing and condemning the whole ... But there is nothing outside the whole! ... Only then is the innocence of becoming restored