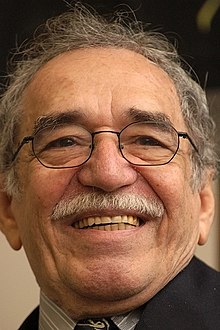

Gabriel García Márquez

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Gabriel José García Márquez (6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, journalist and activist. He was awarded the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Quotes[edit]

- ...a lie is more comfortable than doubt, more useful than love, more lasting than truth ...

- The Autumn of the Patriarch. HarperCollins. 2006 [1976]. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-06-088286-0. translated from El Ontoño del Patriarica (1975) by Gregory Rabassa

- Santiago Nasar had often told me that the smell of closed-in flowers had an immediate relation to death for him.

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), trans. Gregory Rabassa [Ballantine, 1984, ISBN 0-345-31002-0], p. 47

- Since the appearance of visible life on Earth, 380 million years had to elapse in order for a butterfly to learn how to fly; 180 million years to create a rose with no other commitment than to be beautiful; and four geological eras in order for us human beings to be able to sing better than birds, and to be able to die from love. It is not honorable for the human talent, in the golden age of science, to have conceived the way for such an ancient and colossal process to return to the nothingness from which it came through the simple act of pushing a button.

- Speaking of nuclear weapons in “The Cataclysm of Damocles” (1986)

- The most prosperous countries have succeeded in accumulating powers of destruction such as to annihilate, a hundred times over, not only all the human beings that have existed to this day, but also the totality of all living beings that have ever drawn breath on this planet of misfortune.

On a day like today, my master William Faulkner said, "I decline to accept the end of man." I would fall unworthy of standing in this place that was his, if I were not fully aware that the colossal tragedy he refused to recognize thirty-two years ago is now, for the first time since the beginning of humanity, nothing more than a simple scientific possiblity. Faced with this awesome reality that must have seemed a mere utopia through all of human time, we, the inventors of tales, who will believe anything, feel entitled to believe that it is not yet too late to engage in the creation of the opposite utopia. A new and sweeping utopia of life, where no one will be able to decide for others how they die, where love will prove true and happiness be possible, and where the races condemned to one hundred years of solitude will have, at last and forever, a second opportunity on earth.

The Paris Review interview (1981)[edit]

- The Art of Fiction, #69: Interview with Peter H. Stone in The Paris Review, Issue 82 (Winter 1981); later published in The Paris Review Interviews: Writers at Work, Sixth Series (Viking/Penguin, 1984, ISBN 0-140-07736-7

- It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there's not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality. The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.

- p. 322

- In the end all books are written for your friends. The problem after writing One Hundred Years of Solitude was that now I no longer know whom of the millions of readers I am writing for; this upsets and inhibits me. It's like a million eyes are looking at you and you don't really know what they think.

- p. 322

- Interviewer: You describe seemingly fantastic events in such minute detail that it gives them their own reality. Is this something you have picked up from journalism?

García Márquez: That's a journalistic trick which you can also apply to literature. If you say that there are elephants flying in the sky, people are not going to believe you. But if you say that there are four hundred and twenty-five elephants in the sky, people will probably believe you.- p. 324

- Ultimately, literature is nothing but carpentry.

- p. 325

- I would like for my books to have been recognized posthumously, at least in capitalist countries, where they turn you into a kind of merchandise.

- p. 336

- A famous writer who wants to continue writing has to be constantly defending himself against fame. I don't really like to say this because it never sounds sincere, but I would really have liked for my books to have been published after my death, so I wouldn't have to go through all this business of fame and being a great writer. In my case, the only advantage to fame is that I have been able to give it a political use. Otherwise, it is quite uncomfortable. The problem is that you're famous for twenty-four hours a day, and you can't say, "Okay, I won't be famous until tomorrow," or press a button and say, "I won't be famous here or now."

- p. 337

- I can't think of any one film that improved on a good novel, but I can think of many good films that came from very bad novels.

- p. 338

- I was asked the other day if I would be interested in the Nobel Prize, but I think that for me it would be an absolute catastrophe. I would certainly be interested in deserving it, but to receive it would be terrible. It would just complicate even more the problems of fame. The only thing I really regret in life is not having a daughter.

- p. 339

Living to Tell the Tale (2002)[edit]

- Vivir para contarla as translated by Edith Grossman (2004), Vintage International. ISBN 1-4000-3454-X

- Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.

- Before adolescence, memory is more interested in the future than the past...

- Nostalgia, as always, had wiped away bad memories and magnified the good ones.

- Now you don't have to say yes because your heart is saying it for you.

- Children's lies are signs of great talent.

- But I believe without any doubt at all that our greatest good fortune was that even in the most extreme difficulties we might lose our patience but never our sense of humor.

- It was impossible to conceive of two creatures so different who got along so well and loved each other so much.

- From the time they turned one they were tossed from the balconies of the kitchens, first with life preserves so they would lose their fear of the water, and then without life preservers so they would lose their respect for death.

- "There are no two men in this world more similar than you and him," she told me. "And that's the worst thing for having a conversation."

- … no sooner had you done something than someone else appeared who threatened to do it better.

- … nothing was easy, least of all surviving Sunday afternoons without love.

- … my unhealthy timidity might be a great obstacle to me in my life.

- Because for you, quitting smoking would be like killing someone you love.

- Until I discovered the miracle that all things that sound are music, including dishes and silverware in the dishwasher, as long as they fulfill the illusion of showing us where life is heading.

- I couldn't tell you because even I don't know who I am yet.

- … for an instant I thought about stopping the cab to say goodbye, but I preferred not to defy again a destiny as uncertain and persistent as mine.

Quotes about Gabriel García Márquez[edit]

- For the majority of readers, Latin American fantastic literature operates under the tutelage of the great masters: Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez. However, although few are acquainted with their works, many women began experimenting with this genre well before their male counterparts and were the true precursors of the form, though their names remained on the shelves of oblivion, without the recognition that they deserved. María Luisa Bombal, for example, wrote the fantastic nouvelle, House of Mist (1937) before the famous Ficciones (1944) of Borges, and the Mexican, Elena Garro, wrote Remembrance of Things to Come (1962) before the publication of García Márquez' One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967).

- Marjorie Agosín "Reflections on the Fantastic" Translated from the Spanish by Celeste Kostopulos-Cooperman. In Secret Weavers: Stories of the Fantastic by Women Writers of Argentina and Chile (1992)

- I had already read One-hundred Years of Solitude when I was in college, probably because that was when it was translated into English. I sent a copy in Spanish to my parents, saying, “Look this is just like our family stories!” And they said, “Yes, this is like our story-telling tradition.”

- Kathleen Alcalá Interview (2021)

- I belong to the first generation of Latin American writers brought up reading other Latin American writers. Before my time the work of Latin American writers was not well distributed, even on our continent. In Chile it was very hard to read other writers from Latin America. My greatest influences have been all the great writers of the Latin American Boom in literature: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Cortázar, Borges, Paz, Rulfo, Amado, etc.

- One of the first people I read was García Márquez and One Hundred Years of Solitude when I was about nineteen or eighteen. And Julio Cortázar. I read all of Jorge Amado. I can tell you I read everybody and everything. And they would drive me nuts! But I was compelled to it. I was driven to the mechanics of what they were doing.

- Ana Castillo 1991 interview in Conversations with Contemporary Chicana and Chicano Writers edited by Hector A. Torres (2007)

- (When did you notice this change with publishers-when they finally started publishing Latinos?) JOC: I think it was a couple of years after Gabriel García Márquez won the Nobel Prize and the so-called Latino boom began. All of a sudden people said, "Hey, these guys may have something important to say."

- Judith Ortiz Cofer, interview (2000) in A Poet's Truth: Conversations with Latino/Latina Poets

- Puerto Rico, like all the countries of the Caribbean, is a nation where fantastic reality, the world of magic, is ever present. There are various sects of white magic, such as Santeria. It is a reality that is very palpable in our environment, and this is why there are no great differences between fantasy and reality. This is also true in the work of writers like García Márquez, whom I consider a Caribbean writer because Aracataca, which is the setting for the imaginary Macondo, is in the Caribbean. All Caribbean writers have this in common.

- Rosario Ferré Interviews with Latin American Writers by Gazarian Gautier (1988)

- Such a lovely man.

- Nadine Gordimer Interview (2004)

- They thought Gabriel García Márquez's would be the way, because of his richness, because his work can be multilayer. He can use the Indian past and the Catholic-Spanish heritage. Keep it all. You don't have to cut that out, cut this out.

- 1989 interview in Conversations with Maxine Hong Kingston (1998)

- Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and Gabriel García Márquez. They’ve all been major influences on my work.

- Erika Sánchez interview (2022)

- In One Hundred Years of Solitude,/Márquez wrote that we are birthed/by our mothers only once, but life obligates/us to give birth/to ourselves over and over.

- Erika Sánchez in the poem "Amá"

External links[edit]

- Gabriel García Márquez at Nobelprize.org

- García Márquez, Gabriel. Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez reading the first chapter of One Hundred Years of Solitude (in Spanish).

- Interview with Gabriel García Márquez (1998)

- Gabo – The Creation of Gabriel García Márquez. Documentary, Germany, 2015, 90 min.

- Love in the time of cholera : contains description of the wreck of the San José at Cartagena de Indias