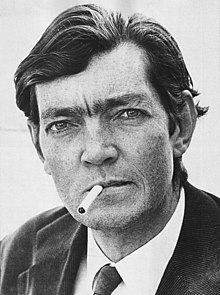

Julio Cortázar

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Julio Cortázar (August 26, 1914 – February 12, 1984) was an Argentine intellectual and author of several experimental novels and many short stories.

| This article on an author is a stub. You can help Wikiquote by expanding it. |

Sourced[edit]

Rayuela (Hopscotch) (1963)[edit]

- 'Andábamos sin buscarnos pero sabiendo que andábamos para encontrarnos.'

- Translation: We went around without looking for each other, but knowing we went around to find each other.

- Chapter 1.

- I touch your mouth, I touch the edge of your mouth with my finger, I am drawing it as if it were something my hand was sketching, as if for the first time your mouth opened a little, and all I have to do is close my eyes to erase it and start all over again, every time I can make the mouth I want appear, the mouth which my hand chooses and sketches on your face, and which by some chance that I do not seek to understand coincides exactly with your mouth which smiles beneath the one my hand is sketching on you.

- You look at me, from close up you look at me, closer and closer and then we play cyclops, we look closer and closer at one another and our eyes get larger, they come closer, they merge into one and the two cyclopses look at each other, blending as they breathe, our mouths touch and struggle in gentle warmth, biting each other with their lips, barely holding their tongues on their teeth, playing in corners where a heavy air comes and goes with an old perfume and a silence. Then my hands go to sink into your hair, to cherish slowly the depth of your hair while we kiss as if our mouths were filled with flowers or with fish, with lively movements and dark fragrance. And if we bite each other the pain is sweet, and if we smother each other in a brief and terrible sucking in together of our breaths, that momentary death is beautiful. And there is but one saliva and one flavor of ripe fruit, and I feel you tremble against me like a moon on the water.

- Chapter 7

- Nada está perdido si se tiene el valor de proclamar que todo está perdido y hay que empezar de nuevo.

- Translation: Nothing is lost if one has the courage to proclaim that all is lost and we must begin anew.

- Chapter 71.

Historias de Cronopios y de Famas (1962)[edit]

- 'Ahora pasa que las tortugas son grandes admiradoras de la velocidad, como es natural. Las esperanzas lo saben, y no se preocupan. Los famas lo saben, y se burlan. Los cronopios lo saben, y cada vez que encuentran una tortuga, sacan la caja de tizas de colores y sobre la redonda pizarra de la tortuga dibujan una golondrina.'

- Translation: Now it happens that turtles are great speed enthusiasts, which is natural.

The esperanzas know that and don't bother themselves about it.

The famas know it, and make fun of it.

The cronopios know it, and each time they meet a turtle, they haul out the box of colored chalks, and on the rounded blackboard of the turtle's shell they draw a swallow.

- Translation: Now it happens that turtles are great speed enthusiasts, which is natural.

- "Hair loss and retrieval" (Translation of "Pérdida y recuperación del pelo")

- To combat pragmatism and the horrible tendency to achieve useful purposes, my elder cousin proposes the procedure of pulling out a nice hair from the head, knotting it in the middle and droping it gently down the hole in the sink. If the hair gets caught in the grid that usually fills in these holes, it will just take to open the tap a little to lose sight of it.

- Without wasting an instant, must start the hair recovery task. The first operation is reduced to dismantling the siphon from the sink to see if the hair has become hooked in any of the rugosities of the drain. If it is not found, it is necessary to expose the section of pipe that goes from the siphon to the main drainage pipe. It is certain that in this part will appear many hairs and we will have to count on the help of the rest of the family to examine them one by one in search of the knot. If it does not appear, the interesting problem of breaking the pipe down to the ground floor will arise, but this means a greater effort, because for eight or ten years we will have to work in a ministry or trading house to collect enough money to buy the four departments located under the one of my elder cousin, all that with the extraordinary disadvantage of what while working during those eight or ten years, the distressing feeling that the hair is no longer in the pipes anymore can not be avoided and that only by a remote chance remains hooked on some rusty spout of the drain.

- The day will come when we can break the pipes of all the departments, and for months to come we will live surrounded by basins and other containers full of wet hairs, as well as of assistants and beggars whom we will generously pay to search, assort, and bring us the possible hairs in order to achieve the desired certainty. If the hair does not appear, we will enter in a much more vague and complicated stage, because the next section takes us to the city's main sewers. After buying a special outfit, we will learn to slip through the sewers at late night hours, armed with a powerful flashlight and an oxygen mask, and explore the smaller and larger galleries, assisted if possible by individuals of the underworld, with whom we will have established a relationship and to whom we will have to give much of the money that we earn in a ministry or a trading house.

- Very often we will have the impression of having reached the end of the task, because we will find (or they will bring us) similar hairs of the one we seek; but since it is not known of any case where a hair has a knot in the middle without human hand intervention, we will almost always end up with the knot in question being a mere thickening of the caliber of the hair (although we do not know of any similar case) or a deposit of some silicate or any oxide produced by a long stay against a wet surface. It is probable that we will advance in this way through various sections of major and minor pipes, until we reach that place where no one will decide to penetrate: the main drain heading in the direction of the river, the torrential meeting of detritus in which no money, no boat, no bribe will allow us to continue the search.

- But before that, and perhaps much earlier, for example a few centimeters from the mouth of the sink, at the height of the apartment on the second floor, or in the first underground pipe, we may happen to find the hair. It is enough to think of the joy that this would cause us, in the astonished calculation of the efforts saved by pure good luck, to choose, to demand practically a similar task, that every conscious teacher should advise to its students from the earliest childhood, instead of drying their souls with the rule of cross-multiplication or the sorrows of Cancha Rayada.

Un tal Lucas (1979)[edit]

- 'AMOR 77'

- Y después de hacer todo lo que hacen, se levantan, se bañan, se entalcan, se perfuman, se peinan, se visten, y así progresivamente van volviendo a ser lo que no son.

- Translation: LOVE 77

- And after doing all they do they rise from their bed, they bathe, powder and perfume their persons, they dress, and gradually return to being what they are not.

Julio Cortázar (1975)[edit]

- "The snail lives the way I like to live; he carries his own home with him."

- "The only true exile is the writer who lives in his own country."

Quotes about Julio Cortázar[edit]

- For the majority of readers, Latin American fantastic literature operates under the tutelage of the great masters: Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez. However, although few are acquainted with their works, many women began experimenting with this genre well before their male counterparts and were the true precursors of the form, though their names remained on the shelves of oblivion, without the recognition that they deserved. María Luisa Bombal, for example, wrote the fantastic nouvelle, House of Mist (1937) before the famous Ficciones (1944) of Borges, and the Mexican, Elena Garro, wrote Remembrance of Things to Come (1962) before the publication of García Márquez' One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967).

- Marjorie Agosín "Reflections on the Fantastic" Translated from the Spanish by Celeste Kostopulos-Cooperman. In Secret Weavers: Stories of the Fantastic by Women Writers of Argentina and Chile (1992)

- Julio was never a regional writer. You could see he was Argentinian, but he was more like Borges, more universal from the very beginning. He didn’t jump from the regionalism, he wrote universally all the time...It’s not that Julio was not very Argentinian, he was very Argentinian but his works were never as local.

- Claribel Alegría Interview with Bomb Magazine (2000)

- I belong to the first generation of Latin American writers brought up reading other Latin American writers. Before my time the work of Latin American writers was not well distributed, even on our continent. In Chile it was very hard to read other writers from Latin America. My greatest influences have been all the great writers of the Latin American Boom in literature: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Cortázar, Borges, Paz, Rulfo, Amado, etc.

- I was influenced by all of them-by García Márquez, by Carlos Fuentes, Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, José Donoso, so many of them-some of my own generation, like Eduardo Galeano. It's easy for me to write because I don't have to invent anything. They already found a voice, a way of telling us to ourselves, so it's easy.

- 1994 interview in Conversations with Isabel Allende (1999)

- I have a commitment to many of my major characters who have brown skin. That's a commitment to the story of a different character that you're not used to seeing in literature. In Julio Cortázar's work, for example, I can deal with his Latin American history, I can deal with the language, but his women have white, porcelain skin. They're Argentine, probably from a European background.

- Ana Castillo 1991 interview in Conversations with Contemporary Chicana and Chicano Writers edited by Hector A. Torres (2007)

- One of the first people I read was García Márquez and One Hundred Years of Solitude when I was about nineteen or eighteen. And Julio Cortázar. I read all of Jorge Amado. I can tell you I read everybody and everything. And they would drive me nuts! But I was compelled to it. I was driven to the mechanics of what they were doing...I read and reread Julio Cortázar to try to learn from the writer the labyrinth of his style...I think he is one of the best examples of playing with time. When I was going to write The Mixquiahuala Letters I was twenty-three, and I had this idea about playing with time-that time was fluid-and I mentioned this project to a friend of mine, who was getting his Master's in Spanish literature, and he said that's already been done!

- Ana Castillo 1991 interview in Conversations with Contemporary Chicana and Chicano Writers edited by Hector A. Torres (2007)

- Cortázar…whom I admire deeply, I met much later in my life...Cortázar is the one who is closest to my way of understanding the act of writing. And nearer to my heart. I admire Carlos Fuentes on the opposite extreme of the equation. That is why I wrote a book on both of them, Entrecruzamientos: Cortázar/Fuentes.

- Luisa Valenzuela Interview (2018)

- Cualquiera que no lea a Cortázar está condenado. No leerlo es una seria enfermedad invisible que, con el tiempo, puede traer consecuencias terribles. Semejante en cierto modo al que nunca ha saboreado un durazno, el hombre se volverá calladamente más triste, notablemente más pálido y es probable que, poco a poco, acabe perdiendo todo el pelo.

- Anyone who doesn't read Cortázar is doomed. Not to read him is a grave invisible disease which in time can have terrible consequences. Something similar to a man who had never tasted peaches. He would be quietly getting sadder, noticeably paler, and probably little by little, he would lose his hair.