John von Neumann

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

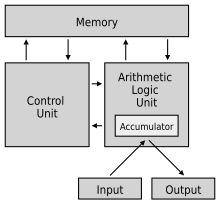

John von Neumann (28 December 1903 – 8 February 1957) was a Hungarian-American-Jewish mathematician, physicist, inventor, computer scientist, and polymath. He made major contributions to a number of fields, including mathematics (foundations of mathematics, functional analysis, ergodic theory, geometry, topology, and numerical analysis), physics (quantum mechanics, hydrodynamics and quantum statistical mechanics), economics (game theory), computing (Von Neumann architecture, linear programming, self-replicating machines, stochastic computing), and statistics.

Quotes[edit]

- I think that it is a relatively good approximation to truth — which is much too complicated to allow anything but approximations — that mathematical ideas originate in empirics. But, once they are conceived, the subject begins to live a peculiar life of its own and is … governed by almost entirely aesthetical motivations. In other words, at a great distance from its empirical source, or after much "abstract" inbreeding, a mathematical subject is in danger of degeneration. Whenever this stage is reached the only remedy seems to me to be the rejuvenating return to the source: the reinjection of more or less directly empirical ideas.

- "The Mathematician", in The Works of the Mind (1947) edited by R. B. Heywood, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- For progress there is no cure.... The only safety possible is relative, and it lies in an intelligent exercise of day-to-day judgement.

- "Can we survive Technology?" 1950.[1]

- Any one who considers arithmetical methods of producing random digits is, of course, in a state of sin. For, as has been pointed out several times, there is no such thing as a random number — there are only methods to produce random numbers, and a strict arithmetic procedure of course is not such a method.

- On mistaking pseudorandom number generators for being truly "random" — this quote is often erroneously interpreted to mean that von Neumann was against the use of pseudorandom numbers, when in reality he was cautioning about misunderstanding their true nature while advocating their use. From "Various techniques used in connection with random digits" by John von Neumann in Monte Carlo Method (1951) edited by A.S. Householder, G.E. Forsythe, and H.H. Germond

- The total subject of mathematics is clearly too broad for any one of us. I do not think that any mathematician since Gauss has covered it fully and uniformly, even Hilbert did not, and all of us are of considerably lesser width (quite apart from the question of depth) than Hilbert. It would therefore, be quite unrealistic not to admit, that any address I could possibly give would not be biased towards some areas in mathematics in which I have had some experience, to the detriment of others which may be equally or more important. To be specific, I could not avoid a bias towards those parts of analysis, logics, and certain border areas of the applications of mathematics to other sciences in which I have worked. If your Committee feels that an address which is affected by such imperfections still fits into the program of the Congress, and if the very generous confidence in my ability to deliver continues, I shall be glad to undertake it.

- Letter to H. D. Kloosterman (April 10, 1953), unpublished, John von Neumann Archive, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., as quoted by Miklós Rédei, 1999. "Unsolved Problems in Mathematics": J. von Neumann's Address to the International Congress of Mathematicians, Amsterdam, September 2-9, 1954 in Mathematical Intelligencer, 21(4), 7–12.

- A large part of mathematics which becomes useful developed with absolutely no desire to be useful, and in a situation where nobody could possibly know in what area it would become useful; and there were no general indications that it ever would be so. By and large it is uniformly true in mathematics that there is a time lapse between a mathematical discovery and the moment when it is useful; and that this lapse of time can be anything from 30 to 100 years, in some cases even more; and that the whole system seems to function without any direction, without any reference to usefulness, and without any desire to do things which are useful.

- "The Role of Mathematics in the Sciences and in Society" (1954) an address to Princeton alumni, published in John von Neumann : Collected Works (1963) edited by A. H. Taub ; also quoted in Out of the Mouths of Mathematicians : A Quotation Book for Philomaths (1993) by R. Schmalz

- The sciences do not try to explain, they hardly even try to interpret, they mainly make models. By a model is meant a mathematical construct which, with the addition of certain verbal interpretations, describes observed phenomena. The justification of such a mathematical construct is solely and precisely that it is expected to work.

- "Method in the Physical Sciences", in The Unity of Knowledge (1955), ed. L. G. Leary (Doubleday & Co., New York), p. 157

- It is exceptional that one should be able to acquire the understanding of a process without having previously acquired a deep familiarity with running it, with using it, before one has assimilated it in an instinctive and empirical way… Thus any discussion of the nature of intellectual effort in any field is difficult, unless it presupposes an easy, routine familiarity with that field. In mathematics this limitation becomes very severe.

- As quoted in "The Mathematician" in The World of Mathematics (1956), by James Roy Newman

- When we talk mathematics, we may be discussing a secondary language built on the primary language of the nervous system.

- As quoted in John von Neumann, 1903-1957 (1958) by John C. Oxtoby and B. J. Pettis, p. 128

- It is just as foolish to complain that people are selfish and treacherous as it is to complain that the magnetic field does not increase unless the electric field has a curl. Both are laws of nature.

- As quoted "John von Neumann (1903 - 1957)" by Eugene Wigner, in Year book of the American Philosophical Society (1958); later in Symmetries and Reflections : Scientific Essays of Eugene P. Wigner (1967), p. 261

- You should call it entropy, for two reasons. In the first place your uncertainty function has been used in statistical mechanics under that name, so it already has a name. In the second place, and more important, no one really knows what entropy really is, so in a debate you will always have the advantage.

- Suggesting to Claude Shannon a name for his new uncertainty function, as quoted in Scientific American Vol. 225 No. 3, (1971), p. 180.

- Young man, in mathematics you don't understand things. You just get used to them.

- Reply, according to Dr. Felix T. Smith of Stanford Research Institute, to a physicist friend who had said "I'm afraid I don't understand the method of characteristics," as quoted in The Dancing Wu Li Masters: An Overview of the New Physics (1979) by Gary Zukav, Bantam Books, p. 208, footnote.

- You don't have to be responsible for the world that you're in.

- Advice given by von Neumann to Richard Feynman as quoted in "Los Alamos from Below" in Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (1985).

- The goys have proven the following theorem…

- Statement at the start of a classroom lecture, as quoted in 1,911 Best Things Anyone Ever Said (1988) by Robert Byrne.

- The calculus was the first achievement of modern mathematics and it is difficult to overestimate its importance. I think it defines more unequivocally than anything else the inception of modern mathematics; and the system of mathematical analysis, which is its logical development, still constitutes the greatest technical advance in exact thinking.

- As quoted in Bigeometric Calculus: A System with a Scale-Free Derivative (1983) by Michael Grossman, and in Single Variable Calculus (1994) by James Stewart.

- With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk.

- Attributed to von Neumann by Enrico Fermi, as quoted by Freeman Dyson in "A meeting with Enrico Fermi" in Nature 427 (22 January 2004) p. 297

- You wake me up early in the morning to tell me that I'm right? Please wait until I'm wrong.

- As quoted by Jacob Bronowski in The Ascent of Man TV series

- If one has really technically penetrated a subject, things that previously seemed in complete contrast, might be purely mathematical transformations of each other.

- As quoted in Proportions, Prices, and Planning (1970) by András Bródy

- If people do not believe that mathematics is simple, it is only because they do not realize how complicated life is.

- Remark made by von Neumann as keynote speaker at the first national meeting of the Association for Computing Machinery in 1947, as mentioned by Franz L. Alt at the end of "Archaeology of computers: Reminiscences, 1945--1947", Communications of the ACM, volume 15, issue 7, July 1972, special issue: Twenty-fifth anniversary of the Association for Computing Machinery, p. 694.

- There probably is a God. Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn't.

- As quoted in John Von Neumann : The Scientific Genius Who Pioneered the Modern Computer, Game Theory, Nuclear Deterrence and Much More (1992) by Norman Macrae, p. 379

- If you say why not bomb them tomorrow, I say why not today? If you say today at five o' clock, I say why not one o' clock?

- As quoted in "The Passing of a Great Mind" by Clay Blair, Jr., in LIFE Magazine (25 February 1957), p. 96

- Some people confess guilt to claim credit for the sin.

- As quoted in John Von Neumann: The Scientific Genius Who Pioneered the Modern Computer, Game Theory, Nuclear Deterrence, and Much More (2016) by Norman Macrae, p. 352 in response to Oppenheimer's 'destroyer of worlds' quote.

- It will not be sufficient to know that the enemy has only fifty possible tricks and that we can counter every one of them, but we must be able to counter them almost at the very instant they occur.

- As quoted in Defense in Atomic War by John von Neumann. Paper delivered at a symposium in honor of Dr. R. H. Kent, December 7, 1955, The Scientific Bases of Weapons, Journ. Am. Ordnance Assoc., 21–23, 1955.

Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (1932)[edit]

Quotes about von Neumann[edit]

- Sorted alphabetically by author or source

- Von Neumann had an absolute paranoia about the Russians and favored a first nuclear strike. Einstein referred to him as a Denktier, a think animal.

- He would seize on the fuzzy notions of others and, by dint of his prodigious mental powers, leap five blocks ahead of the pack. “You would tell him something garbled, and he’d say, ‘Oh, you mean the following,’ and it would come back beautifully stated,” said his onetime protégé, the Harvard mathematician Raoul Bott.

- Raou Bott, quoted in Holt, Jim. "How the Computers Exploded | Jim Holt" (in en). ISSN 0028-7504.

- I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann's does not indicate a species superior to that of man.

- Hans Bethe of Cornell University, as quoted in LIFE Magazine (1957), pp. 89-104

- All people who had met him and interacted with him realized that his brain was more powerful than anyone’s they have ever encountered. I remember Hans Bethe even said, only half in jest, that von Neumann’s brain was a new development of the human brain. Only a slight exaggeration.

- I went in and started telling him about my thesis. He listened for about ten minutes and asked me a couple of questions, and then he started telling me about my thesis. What you have really done is this, and probably this is true, and you could have done it in a somewhat simpler way, and so on. He was a really remarkable man. He listened to me talk about this rather obscure subject and in ten minutes he knew more about it than I did. He was extremely quick. I think he may have wasted a certain amount of time, by the way, because he was so willing to listen to second- or third-rate people and think about their problems. I saw him do that on many occasions.

- David Blackwell, as quoted in Out of the Mouths of Mathematicians : A Quotation Book for Philomaths (1993) by Rosemary Schmalz, p. 213

- quoted DeGroot, Morris H. "A conversation with David Blackwell." Statistical Science 1.1 (1986): 40-53.

- In a Silliman lecture ... John von Neumann, who was dying at the time, wrote some of the most splendid sentences he wrote in all his life ... He pointed out that there were good grounds merely in terms of electrical analysis to show that the mind, the brain itself, could not be working on a digital system. It did not have enough accuracy; or ... it did not have enough memory. ... And he wrote some classical sentences saying there is a statistical language in the brain ... different from any other statistical language that we use... this is what we have to discover. ...I think we shall make some progress along the lines of looking for what kind of statistical language would work.

- Jacob Bronowski, The Origins of Knowledge and Imagination (1978); referring to von Neumann's, The Computer and the Brain (1958)

- In a 1948 Princeton talk, replying to a frequent affirmation that it's impossible to build a machine that can replace the human mind, von Neumann said: You insist that there is something that a machine can't do. If you will tell me precisely what it is that a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine which will do just that.

- Edwin Thompson Jaynes, Probability Theory: The Logic of Science (2003); referring to the 1948 Princeton talk he attended to.

- Later, Tucker told me that he had gone to von Neumann and said, ‘This seems like very interesting work, but I can’t evaluate it. I don’t know whether it should really be called mathematics.’ Von Neumann replied, ‘Well, if it isn’t now, it will be someday—let’s encourage it.’ So I got my Ph.D.”

- Marvin Minsky, quoted it Bernstein, Jeremy (1981-12-06). "Marvin Minsky’s Vision of the Future" (in en-US). The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X.

- Bennie decided to approach Johnnie on the matter and arranged to travel to Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, headed up at the time by Oppenheimer, where Johnnie (and lesser geniuses such as Albert Einstein) was stationed.

- Samuel T. Cohen , physicist and inventor of the Neutron Bomb

- I remember a talk that Von Neumann gave at Princeton around 1950, describing the glorious future which he then saw for his computers. Most of the people that he hired for his computer project in the early days were meteorologists. Meteorology was the big thing on his horizon. He said, as soon as we have good computers, we shall be able to divide the phenomena of meteorology cleanly into two categories, the stable and the unstable. The unstable phenomena are those which are upset by small disturbances, the stable phenomena are those which are resilient to small disturbances. He said, as soon as we have some large computers working, the problems of meteorology will be solved. All processes that are stable we shall predict. All processes that are unstable we shall control. He imagined that we needed only to identify the points in space and time at which unstable processes originated, and then a few airplanes carrying smoke generators could fly to those points and introduce the appropriate small disturbances to make the unstable processes flip into the desired directions. A central committee of computer experts and meteorologists would tell the airplanes where to go in order to make sure that no rain would fall on the Fourth of July picnic. This was John von Neumann's dream. This, and the hydrogen bomb, were the main practical benefits which he saw arising from the development of computers.

- Freeman Dyson, in an account of a 1950 talk by von Neumann, in Infinite in All Directions (1988); the statement "All stable processes we shall predict. All unstable processes we shall control" is sometimes attributed to von Neumann directly, but may be a paraphrase.

- The only student of mine I was ever intimidated by. He was so quick. There was a seminar for advanced students in Zürich that I was teaching and von Neumann was in the class. I came to a certain theorem, and I said it is not proved and it may be difficult. Von Neumann didn't say anything but after five minutes he raised his hand. When I called on him he went to the blackboard and proceeded to write down the proof. After that I was afraid of von Neumann.

- George Pólya, in How to Solve It (1957) 2nd edition, p. xv; also in The Pólya Picture Album (1987), p. 154

- I have come to suspect that to most people thinking is painful. Some of us are addicted to thinking. Some of us find it a necessity. Johnny enjoyed it. I even have the suspicion that he enjoyed practically nothing else.

- Edward Teller, in John Von Neumann: a documentary, Amram Nowak and Patricia Powell, Mathematical Association of America, 1966.

- He could and did talk to my 3-year-old son on his own terms, and I sometimes wondered whether his relation to the rest of us were a little bit similar.

- Edward Teller, in John Von Neumann: a documentary, Amram Nowak and Patricia Powell, Mathematical Association of America, 1966.

- Quite aware that the criteria of value in mathematical work are, to some extent, purely aesthetic, he once expressed an apprehension that the values put on abstract scientific achievement in our present civilization might diminish: "The interests of humanity might change, the present curiosities in science may cease, and entirely different things may occupy the human mind in the future." One conversation centered on the ever accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, which gives the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue.

- Stanislaw Ulam, "John von Neumann, 1903-1957" Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 64, no.3, part 2 (May 1958)

- Machines creating new machines

After the last visitor had departed Von Neumann would retire to his second-floor study to work on the paper which he knew would be his last contribution to science. It was an attempt to formulate a concept shedding new light on the workings of the human brain. He believed that if such a concept could be stated with certainty, it would also be applicable to electronic computers and would permit man to make a major step forward in using these 'automata'. In principle, he reasoned, there was no reason why some day a machine might not be built which not only could perform most of the functions of the human brain but could actually reproduce itself, i.e., create more supermachines like it. He proposed to present this paper at Yale, where he had been invited to give the 1956 Silliman Lectures.- "Passing of a Great Mind: John von Neumann, a Brilliant, Jovial Mathematician, was a Prodigious Servant of Science and his Country", Clary Blair Jr., Life 25 February 1957, pg89-104

- Throughout much of his career, he led a double life: as an intellectual leader in the ivory tower of pure mathematics and as a man of action, in constant demand as an advisor, consultant and decision-maker to what is sometimes called the military-industrial complex of the United States. My own belief is that these two aspects of his double life, his wide-ranging activities as well as his strictly intellectual pursuits, were motivated by two profound convictions. The first was the overriding responsibility that each of us has to make full use of whatever intellectual capabilities we were endowed with. He had the scientist's passion for learning and discovery for its own sake and the genius's ego-driven concern for the significance and durability of his own contributions. The second was the critical importance of an environment of political freedom for the pursuit of the first, and for the welfare of mankind in general.

I'm convinced, in fact, that all his involvements with the halls of power were driven by his sense of the fragility of that freedom. By the beginning of the 1930s, if not even earlier, he became convinced that the lights of civilization would be snuffed out all over Europe by the spread of totalitarianism from the right: Nazism and Fascism. So he made an unequivocal commitment to his home in the new world and to fight to preserve and reestablish freedom from that new beachhead.

In the 1940s and 1950s, he was equally convinced that the threat to civilization now came from totalitarianism on the left, that is, Soviet Communism, and his commitment was just as unequivocal to fighting it with whatever weapons lay at hand, scientific and economic as well as military. It was a matter of utter indifference to him, I believe, whether the threat came from the right or from the left. What motivated both his intense involvement in the issues of the day and his uncompromisingly hardline attitude was his belief in the overriding importance of political freedom, his strong sense of its continuing fragility, and his conviction that it was in the United States, and the passionate defense of the United States, that its best hope lay.- Marina von Neumann Whitman, Introduction to John Von Neumann: Selected Letters, History of Mathematics, Vol. 27, ed. Miklos Redei (2005), pp. xv–xvi

- He was becoming more concerned with defense than with science. But it seemed that he was living proof that one could do science without really belonging to a “guild.” In fact, he was under extreme pressure at Princeton. From there, he left for Washington and was not planning to return. Luckily, von Neumann had realized that, by having failed to claim admission to any guild, I was leading a very dangerous life. A foundation executive told me much later that von Neumann had specifically asked him to watch after me, and to help in case of trouble.

- Benoit Mandelbrot, quoted in Barcellos, Anthony, and A. Barcellos. "Interview of BB Mandelbrot." Mathematical People: Profiles and Interviews (2008): 213-234.

- A deep sense of humor and an unusual ability for telling stories and jokes endeared Johnny even to casual acquaintances. He could be blunt when necessary, but was never pompous. A mind of von Neumann's inexorable logic had to understand and accept much that most of us do not want to accept and do not even wish to understand. This fact colored many of von Neumann's moral judgments. … Only scientific intellectual dishonesty and misappropriation of scientific results could rouse his indignation and ire — but these did — and did almost equally whether he himself, or someone else, was wronged.

- Eugene Wigner, in "John von Neumann (1903 - 1957)" in Year book of the American Philosophical Society (1958); later in Symmetries and Reflections : Scientific Essays of Eugene P. Wigner (1967), p. 261

- One famous story concerns a complicated expression that a young scientist at the Aberdeen Proving Ground needed to evaluate. He spent ten minutes on the first special case; the second computation took an hour of paper and pencil work; for the third he had to resort to a desk calculator, and even so took half a day. When Johnny came to town, the young man showed him the formula and asked him what to do. Johnny was glad to tackle it. "Let's see what happens for the first few cases. If we put n = 1, we get..." -- and he looked into space and mumbled for a minute. Knowing the answer, the young questioner put in "2.31?" Johnny gave him a funny look and said "Now if n = 2, ...", and once again voiced some of his thoughts as he worked. The young man, prepared, could of course follow what Johnny was doing, and, a few seconds before Johnny finished, he interrupted again, in a hesitant tone of voice: "7.49?" This time Johnny frowned, and hurried on: "If n = 3, then...". The same thing happened as before - Johnny muttered for several minutes, the young man eavesdropped, and, just before Johnny finished, the young man exclaimed: "11.06!" That was too much for Johnny. It couldn't be! No unknown beginner could outdo him! He was upset and he sulked till the practical joker confessed.

- Paul Halmos. "The legend of John von Neumann." The American mathematical monthly 80.4 (1973): 382-394.

- Style. As a writer of mathematics von Neumann was clear, but not clean; he was powerful but not elegant. He seemed to love fussy detail, needless repetition, and notation so explicit as to be confusing. To maintain a logically valid but perfectly transparent and unimportant distinction, in one paper he introduced an extension of the usual functional notation: along with the standard he dealt also with something denoted by . The hair that was split to get there had to be split again a little later, and there was , and, ultimately, . Equations such as

have to be peeled before they can be digested; some irreverent students referred to this paper as von Neumann's onion.

- Paul Halmos. "The legend of John von Neumann." The American mathematical monthly 80.4 (1973): 382-394.

- "Most mathematicians prove what they can, von Neumann proves what he wants." Once in a discussion about the rapid growth of mathematics in modern times, von Neumann was heard to remark that whereas thirty years ago a mathematician could grasp all of mathematics, that is impossible today. Someone asked him: "What percentage of all mathematics might a person aspire to understand today?" Von Neumann went into one of his five-second thinking trances, and said: "About 28 percent."

- Lax, Peter. "Remembering John von Neumann." Proc. of Symposia in Pure Mathematics. Vol. 50. 1990.

- The accuracy of his logic was, perhaps, the most decisive character of his mind. One had the impression of a perfect instrument whose gears were machined to mesh accurately to a thousandth of an inch. "If one listens to von Neumann, one understands how the human mind should work," was the verdict of one of our perceptive colleagues... "If he analyzed a problem, it was not necessary to discuss it any further. It was clear what had to be done," said the present chairman of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission.

- "John von Neumann (1903 - 1957)" by Eugene Wigner, in Year book of the American Philosophical Society (1958)

- [On Rayleigh–Taylor instability] So, Fermi said, "Let me make a model; I'll have a broad tongue which moves into the dense material; I'll have a narrow tongue that moves away from it, and I'll just solve this numerically." So, he did some of that, but he wasn't quite satisfied with the solution. One afternoon around 4:50 p.m., John von Neumann came by and saw what Fermi had on the blackboard and asked what he was doing. So, Enrico told him, and John von Neumann said, "That's very interesting." He came back about 15 minutes later and gave him the answer. Fermi leaned against his doorpost and told me, "You know, that man makes me feel I know no mathematics at all."

- Garwin, Richard L. "Working with Fermi at Chicago and Los Alamos." Bulletin of the American Physical Society 55 (2010).

- The mathematician John von Neumann, born Neumann Janos in Budapest in 1903, was incomparably intelligent, so bright that, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Eugene Wigner would say, "only he was fully awake." One night in early 1945, von Neumann woke up and told his wife, Klari, that "what we are creating now is a monster whose influence is going to change history, provided there is any history left. Yet it would be impossible not to see it through." Von Neumann was creating one of the first computers, in order to build nuclear weapons. But, Klari said, it was the computers that scared him the most.

- The Nucleus of the Digital Age (Konstantin Kakaes, 2012), review of Turing's Cathedral by George Dyson.

- What Von Neumann contributed as far as the engineering was concerned, was simply the enormous confidence everybody had that a machine so simple, and with no more doodads on it could knock dead, so to speak, an enormous amount of the computation that needed to be done in this world for the next few decades. He never came over and said to make a circuit of this, but he did know so much more of the deeper aspects of mathematics and the practical aspects of computation than any of the rest of us. What he did essentially, was to serve as this unshakable confidence that said: "Go ahead, nothing else matters, get it running at this speed and this capability, and the rest of it is just a lot of nonsense."

- Julian Bigelow, Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977; Interviewer: Richard R. Mertz; Date: January 20, 1971

- Von Neumann is "an enigma of nature that will have to remain unresolved". His wife.

External links[edit]

- Profile at University of St Andrews

- von Neumann's contribution to economics — International Social Science Review

- Oral history interview with Alice R. Burks and Arthur W. Burks at Charles Babbage Institute

- Oral history interview with Nicholas C. Metropolis, at Charles Babbage Institute

- Von Neumann vs. Dirac — at Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- John von Neumann Postdoctoral Fellowship – Sandia National Laboratories

- Von Neumann's Universe, audio talk by George Dyson

- John von Neumann's 100th Birthday, article by Stephen Wolfram

- Annotated bibliography for John von Neumann from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Budapest Tech Polytechnical Institution – John von Neumann Faculty of Informatics

- John von Neumann speaking at the dedication of the NORD (2 December 1954) — audio recording

- The American Presidency Project

- John Von Neumann Memorial at Find A Grave

Categories:

- 1903 births

- 1957 deaths

- Academics from Hungary

- Academics from the United States

- Mathematicians from Hungary

- Mathematicians from the United States

- Polymaths

- Inventors

- Game theorists

- Economists from Hungary

- Economists from the United States

- American Jews

- Hungarian Jews

- Catholics from the United States

- Physicists from Hungary

- Physicists from the United States

- People from Budapest

- Computer scientists from the United States

- Designers

- Anti-communists from the United States

- Immigrants to the United States

- Princeton University faculty

- Members of the American Philosophical Society