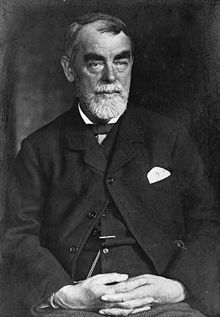

Samuel Butler (novelist)

Appearance

(Redirected from Samuel Butler (1835-1902))

Samuel Butler (December 4, 1835 – June 18, 1902) was a British satirist, most famous for his novels Erewhon and The Way of All Flesh.

- For the 17th-century author of Hudibras, see Samuel Butler (poet)

Quotes

[edit]

- The man who lets himself be bored is even more contemptible than the bore.

- The Fair Haven, Memoir of the Late John Pickard Owen, Ch. 3 (1873)

- "Words, words, words," he writes, "are the stumbling-blocks in the way of truth. Until you think of things as they are, and not of the words that misrepresent them, you cannot think rightly. Words produce the appearance of hard and fast lines where there are none. Words divide; thus we call this a man, that an ape, that a monkey, while they are all only differentiations of the same thing. To think of a thing they must be got rid of: they are the clothes that thoughts wear—only the clothes. I say this over and over again, for there is nothing of more importance. Other men's words will stop you at the beginning of an investigation. A man may play with words all his life, arranging them and rearranging them like dominoes. If I could think to you without words you would understand me better."

- Life and Habit, ch. 5 (1877)

- A hen is only an egg's way of making another egg.

- Life and Habit, ch. 8 (1877)

- Stowed away in a Montreal lumber room

The Discobolus standeth and turneth his face to the wall;

Dusty, cobweb-covered, maimed and set at naught,

Beauty crieth in an attic and no man regardeth:

O God! O Montreal!- A Psalm of Montreal, st. 1 (1884)

- The Discobolus is put here because he is vulgar —

He has neither vest nor pants with which to cover his limbs.- A Psalm of Montreal, st. 5

- Life is like playing a violin solo in public and learning the instrument as one goes on.

- Speech at the Somerville Club, February 27, 1895

- Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another.

- First lines of Butler's translation of The Iliad (1898)

- Life and death are balanced as it were on the edge of a razor.

- The Iliad of Homer, Rendered into English Prose (1898), Book X

- There can be no covenants between men and lions, wolves and lambs can never be of one mind, but hate each other out and out an through.

- The Iliad of Homer, Rendered into English Prose (1898), Book XXII

- Tell me, O muse, of that ingenious hero who traveled far and wide after he had sacked the famous town of Troy. Many cities did he visit, and many were the nations with whose manners and customs he was acquainted; moreover he suffered much by sea while trying to save his own life and bring his men safely home.

- The Odyssey of Homer (1900), opening lines

- God's merits are so transcendent that it is not surprising his faults should be in reasonable proportion.

- "Rebelliousness", Note-Books (1912)

- It is the manner of gods and prophets to begin: "Thou shalt have none other God or Prophet but me." If I were to start as a God or a prophet I think I should take the line: "Thou shalt not believe in me. Thou shalt not have me for a God. Thou shalt worship any d_____d thing thou likest except me." This should be my first and great commandment, and my second should be like unto it.

- Samuel Butler's Notebooks (1912) self censored "d_____d" in original publication

- The most important service rendered by the press and the magazines is that of educating people to approach printed matter with distrust.

- Samuel Butler's Notebooks (1951)

- One of the first businesses of a sensible man is to know when he is beaten, and to leave off fighting at once.

- Samuel Butler's Notebooks (1951)

- A lawyer's dream of heaven: every man reclaimed his own property at the resurrection, and each tried to recover it from all his forefathers.

- Further Extracts from the Note-Books of Samuel Butler, compiled and edited by A.T. Bartholomew (1934), p. 27

- The devil tempted Christ; yes, but it was Christ who tempted the devil to tempt him.

- Further Extracts from the Note-Books of Samuel Butler, compiled and edited by A.T. Bartholomew (1934), p. 76

- To do great work a man must be very idle as well as very industrious.

- Further Extracts from the Note-Books of Samuel Butler, compiled and edited by A.T. Bartholomew (1934), p. 262

- Man is the only animal that laughs and has a state legislature.

- As quoted in 1,911 Best Things Anybody Ever Said (1988) by Robert Byrne

Ramblings In Cheapside (1890)

[edit]

- First published in Universal Review (December 1890)

- The turtle obviously had no sense of proportion; it differed so widely from myself that I could not comprehend it; and as this word occurred to me, it occurred also that until my body comprehended its body in a physical material sense, neither would my mind be able to comprehend its mind with any thoroughness. For unity of mind can only be consummated by unity of body; everything, therefore, must be in some respects both knave and fool to all that which has not eaten it, or by which it has not been eaten. As long as the turtle was in the window and I in the street outside, there was no chance of our comprehending one another. < I knew that I could get it to agree with me if I could so effectually buttonhole and fasten on to it as to eat it. Most men have an easy method with turtle soup, and I had no misgiving but that if I could bring my first premise to bear I should prove the better reasoner. My difficulty lay in this initial process, for I had not with me the argument that would alone compel Mr. Sweeting to think that I ought to be allowed to convert the turtles — I mean I had no money in my pocket. No missionary enterprise can be carried on without any money at all, but even so small a sum as half a crown would, I suppose, have enabled me to bring the turtle partly round, and with many half-crowns I could in time no

turtle needs must go where the money drives. If, as is alleged, the world stands on a turtle, the turtle stands on money. No money no turtle. As for money, that stands on opinion, credit, trust, faith — things that, though highly material in connection with money, are still of immaterial essence.

- We can see nothing face to face; our utmost seeing is but a fumbling of blind finger-ends in an overcrowded pocket.

- The limits of the body seem well defined enough as definitions go, but definitions seldom go far.

- We meet people every day whose bodies are evidently those of men and women long alive

but whose appearance we know through their portraits.

- I do not like books. I believe I have the smallest library of any literary man in London, and I have no wish to increase it. I keep my books at the British Museum and at Mudie's, and it makes me very angry if anyone gives me one for my private library.

- If a man would get hold of the public era, he must pay, marry, or fight.

- I should not advise anyone with ordinary independence of mind to attempt the public ear unless he is confident that he can out-lung and out-last his own generation; for if he has any force, people will and ought to be on their guard against him, inasmuch as there is no knowing where he may not take them.

- We do not know what death is. If we know so little about life which we have experienced, how shall be know about death which we have not — and in the nature of things never can?

- All we know is, that even the humblest dead may live along after all trace of the body has disappeared; we see them doing it in the bodies and memories of these that come after them; and not a few live so much longer and more effectually than is desirable, that it has been necessary to get rid of them by Act of Parliament. It is love that alone gives life, and the truest life is that which we live not in ourselves but vicariously in others, and with which we have no concern. Our concern is so to order ourselves that we may be of the number of them that enter into life — although we know it not.

- Slugs have ridden their contempt for defensive armour as much to death as the turtles their pursuit of it. They have hardly more than skin enough to hold themselves together; they court death every time they cross the road. Yet death comes not to them more than to the turtle, whose defences are so great that there is little left inside to be defended. Moreover, the slugs fare best in the long run, for turtles are dying out, while slugs are not, and there must be millions of slugs all over the world over for every single turtle.

- Propositions prey upon and are grounded upon one another just like living forms. They support one another as plants and animals do; they are based ultimately on credit, or faith, rather than the cash of irrefragable conviction. The whole universe is carried on on the credit system, and if the mutual confidence on which it is based were to collapse, it must itself collapse immediately. Just or unjust, it lives by faith; it is based on vague and impalpable opinion that by some inscrutable process passes into will and action, and is made manifest in matter and in flesh; it is meteoric — suspended in mid-air; it is the baseless fabric of a vision to vast, so vivid, and so gorgeous that no base can seem more broad than such stupendous baselessness, and yet any man can bring it about his ears by being over-curious; when faith fails, a system based on faith fails also.

- Whether the universe is really a paying concern, or whether it is an inflated bubble that must burst sooner or later, this is another matter. If people were to demand cash payment in irrefragable certainty for everything that they have taken hitherto as paper money on the credit of the bank of public opinion, is there money enough behind it all to stand so great a drain even on so great a reserve?

- By a merciful dispensation of Providence university training is almost as costly as it is unprofitable. The majority will thus be always unable to afford it, and will base their opinions on mother wit and current opinion rather than on demonstration.

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler (1912)

[edit]

Part I - Lord, What is Man?

[edit]- All progress is based upon a universal innate desire on the part of every organism to live beyond its income.

- Life, xvi

- We play out our days as we play out cards, taking them as they come, not knowing what they will be, hoping for a lucky card and sometimes getting one, often getting just the wrong one.

- The World, ii

- There is an eternal antagonism of interest between the individual and the world at large. The individual will not so much care how much he may suffer in this world provided he can live in men's good thoughts long after he has left it. The world at large does not so much care how much suffering the individual may either endure or cause in this life, provided he will take himself clean away out of men's thoughts, whether for good or ill, when he has left it.

- The Individual and the World

- Life is the gathering of waves to a head, at death they break into a million fragments each one of which, however, is absorbed at once into the sea of life and helps to form a later generation which comes rolling on till it too breaks.

- Birth and Death, ii

Part II - Elementary Morality

[edit]

- Intellectual over-indulgence is the most gratuitous and disgraceful form which excess can take, nor is there any the consequences of which are more disastrous.

- Intellectual Self-Indulgence

- The extremes of vice and virtue are alike detestable; absolute virtue is as sure to kill a man as absolute vice is, let alone the dullnesses of it and the pomposities of it.

- Vice and Virtue, ii

- God does not intend people, and does not like people, to be too good. He likes them neither too good nor too bad, but a little too bad is more venial with him than a little too good.

- Vice and Virtue, iii

- Sin is like a mountain with two aspects according to whether it is viewed before or after it has been reached: yet both aspects are real.

- Sin

- Morality turns on whether the pleasure precedes or follows the pain. Thus, it is immoral to get drunk because the headache comes after the drinking, but if the headache came first, and the drunkenness afterwards, it would be moral to get drunk.

- Morality

- Morality is the custom of one's country and the current feeling of one's peers. Cannibalism is moral in a cannibal country.

- Cannibalism

- To love God is to have good health, good looks, good sense, experience, a kindly nature and a fair balance of cash in hand.

- God and Man

- Is there any religion whose followers can be pointed to as distinctly more amiable and trustworthy than those of any other? If so, this should be enough. I find the nicest and best people generally profess no religion at all, but are ready to like the best men of all religions.

- Religion

- Heaven is the work of the best and kindest men and women. Hell is the work of prigs, pedants and professional truth-tellers. The world is an attempt to make the best of both.

- Heaven and Hell

- If we are asked what is the most essential characteristic that underlies this word, the word itself will guide us to gentleness, to absence of such things as brow-beating, overbearing manners and fuss, and generally to consideration for other people.

- Gentleman

- Money is the last enemy that shall never be subdued. While there is flesh there is money — or the want of money; but money is always on the brain so long as there is a brain in reasonable order.

- Money

Part III - The Germs of Erewhon and of Life and Habit

[edit]

- We take it that when the state of things shall have arrived which we have been above attempting to describe, man will have become to the machine what the horse and the dog are to man. He will continue to exist, nay even to improve, and will be probably better off in his state of domestication under the beneficent rule of the machines than he is in his present wild state. We treat our horses, dogs, cattle and sheep, on the whole, with great kindness, we give them whatever experience teaches us to be best for them, and there can be no doubt that our use of meat has added to the happiness of the lower animals far more than it has detracted from it; in like manner it is reasonable to suppose that the machines will treat us kindly, for their existence is as dependent upon ours as ours is upon the lower animals.

- Darwin Among the Machines

- Day by day, however, the machines are gaining ground upon us; day by day we are becoming more subservient to them; more men are daily bound down as slaves to tend them, more men are daily devoting the energies of their whole lives to the development of mechanical life. The upshot is simply a question of time, but that the time will come when the machines will hold the real supremacy over the world and its inhabitants is what no person of a truly philosophic mind can for a moment question.

- Darwin Among the Machines

- Our opinion is that war to the death should be instantly proclaimed against them. Every machine of every sort should be destroyed by the well-wisher of his species. Let there be no exceptions made, no quarter shown; let us at once go back to the primeval condition of the race. If it be urged that this is impossible under the present condition of human affairs, this at once proves that the mischief is already done, that our servitude has commenced in good earnest, that we have raised a race of beings whom it is beyond our power to destroy and that we are not only enslaved but are absolutely acquiescent in our bondage.

- Darwin Among the Machines

Part IV - Memory and Design

[edit]

- To be is to think and to be thinkable. To live is to continue thinking and to remember having done so.

- Memory, ii

- Memory and forgetfulness are as life and death to one another. To live is to remember and to remember is to live. To die is to forget and to forget is to die.

- Antithesis

- We are so far identical with our ancestors and our contemporaries that it is very rarely we can see anything that they do not see. It is not unjust that the sins of the fathers should be visited upon the children, for the children committed the sins when in the persons of their fathers.

- Personal Identity

Part V - Vibrations

[edit]- All thinking is of disturbance, dynamical, a state of unrest tending towards equilibrium. It is all a mode of classifying and of criticising with a view of knowing whether it gives us, or is likely to give us, pleasure or no.

- Thinking

- In the highest consciousness there is still unconsciousness, in the lowest unconsciousness there is still consciousness. If there is no consciousness there is no thing, or nothing. To understand perfectly would be to cease to understand at all.

- Equilibrium

Part VI - Mind and Matter

[edit]

- Animals and plants cannot understand our business, so we have denied that they can understand their own. What we call inorganic matter cannot understand the animals' and plants' business, we have therefore denied that it can understand anything whatever.

- Organic and Inorganic

- Moral influence means persuading another that one can make that other more uncomfortable than that other can make oneself.

- Moral Influence

- When we go up to the shelves in the reading-room of the British Museum, how like it is to wasps flying up and down an apricot tree that is trained against a wall, or cattle coming down to drink at a pool!

- Mental and Physical Pabulum

- All eating is a kind of proselytising — a kind of dogmatising — a maintaining that the eater's way of looking at things is better than the eatee's.

- Eating and Proselytising

- We can no longer separate things as we once could: everything tends towards unity; one thing, one action, in one place, at one time. On the other hand, we can no longer unify things as we once could; we are driven to ultimate atoms, each one of which is an individuality. So that we have an infinite multitude of things doing an infinite multitude of actions in infinite time and space; and yet they are not many things, but one thing.

- Unity and Multitude

Part VII - On the Making of Music, Pictures, and Books

[edit]

- Thought pure and simple is as near to God as we can get; it is through this that we are linked with God.

- Thought and Word, i

- Though analogy is often misleading, it is the least misleading thing we have.

- Thought and Word, ii

- The mere fact that a thought or idea can be expressed articulately in words involves that it is still open to question; and the mere fact that a difficulty can be definitely conceived involves that it is open to solution.

- Thought and Word, iv

- Words impede and either kill, or are killed by, perfect thought; but they are, as a scaffolding, useful, if not indispensable, for the building up of imperfect thought and helping to perfect it.

- Thought and Word, vi

- Words are like money; there is nothing so useless, unless when in actual use.

- Thought and Word, viii

- The written law is binding, but the unwritten law is much more so. You may break the written law at a pinch and on the sly if you can, but the unwritten law — which often comprises the written — must not be broken. Not being written, it is not always easy to know what it is, but this has got to be done.

- The Law

- [Ideas] are like shadows — substantial enough until we try to grasp them.

- Ideas

- All things are like exposed photographic plates that have no visible image on them till they have been developed.

- Development

- Always eat grapes downwards — that is, always eat the best grape first; in this way there will be none better left on the bunch, and each grape will seem good down to the last.

- Eating Grapes Downwards

- My notes always grow longer if I shorten them. I mean the process of compression makes them more pregnant and they breed new notes.

- Making Notes

- There is nothing less powerful than knowledge unattached, and incapable of application. That is why what little knowledge I have has done myself personally so much harm. I do not know much, but if I knew a good deal less than that little I should be far more powerful.

- Knowledge is Power

- In art, never try to find out anything, or try to learn anything until the not knowing it has come to be a nuisance to you for some time. Then you will remember it, but not otherwise. Let knowledge importune you before you will hear it. Our schools and universities go on the precisely opposite system.

- Agonising

- Every new idea has something of the pain and peril of childbirth about it; ideas are just as mortal and just as immortal as organised beings are.

- New Ideas

- Critics generally come to be critics by reason not of their fitness for this but of their unfitness for anything else. Books should be tried by a judge and jury as though they were crimes, and counsel should be heard on both sides.

- Criticism

- A great portrait is always more a portrait of the painter than of the painted.

- Portraits

- A man's style in any art should be like his dress — it should attract as little attention as possible.

- A Man's Style

- They say the test of this [literary power] is whether a man can write an inscription. I say “Can he name a kitten?” And by this test I am condemned, for I cannot.

- Literary Power

- When a man is in doubt about this or that in his writing, it will often guide him if he asks himself how it will tell a hundred years hence.

- Writing for a Hundred Years Hence

Part VIII - Handel and Music

[edit]- If you tie Handel's hands by debarring him from the rendering of human emotion, and if you set Bach's free by giving him no human emotion to render — if, in fact, you rob Handel of his opportunities and Bach of his difficulties — the two men can fight after a fashion, but Handel will even so come off victorious.

- Handel and Bach, i

- Handel and Shakespeare have left us the best that any have left us; yet, in spite of this, how much of their lives was wasted.

- Waste

- Honesty consists not in never stealing but in knowing where to stop in stealing, and how to make good use of what one does steal.

- Honesty

Part IX - A Painter's Views on Painting

[edit]

- Sketching from nature is very like trying to put a pinch of salt on her tail. And yet many manage to do it very nicely.

- Sketching from Nature

- Art has no end in view save the emphasising and recording in the most effective way some strongly felt interest or affection.

- Great Art and Sham Art

- An artist's touches are sometimes no more articulate than the barking of a dog who would call attention to something without exactly knowing what. This is as it should be, and he is a great artist who can be depended on not to bark at nothing.

- Inarticulate Touches

- One reason why it is as well not to give very much detail is that, no matter how much is given, the eye will always want more; it will know very well that it is not being paid in full. On the other hand, no matter how little one gives, the eye will generally compromise by wanting only a little more. In either case the eye will want more, so one may as well stop sooner or later. Sensible painting, like sensible law, sensible writing, or sensible anything else, consists as much in knowing what to omit as what to insist upon.

- Detail

- Painters should remember that the eye, as a general rule, is a good, simple, credulous organ — very ready to take things on trust if it be told them with any confidence of assertion.

- The Credulous Eye

- After having spent years striving to be accurate, we must spend as many more in discovering when and how to be inaccurate.

- Accuracy

- The composer is seldom a great theorist; the theorist is never a great composer. Each is equally fatal to and essential in the other.

- Action and Study

- If a man has not studied painting, or at any rate black and white drawing, his eyes are wild; learning to draw tames them. The first step towards taming the eyes is to teach them not to see too much.

- Seeing

- Think of and look at your work as though it were done by your enemy. If you look at it to admire it you are lost.

- Improvement in Art

- The youth of an art is, like the youth of anything else, its most interesting period. When it has come to the knowledge of good and evil it is stronger, but we care less about it.

- Early Art

- It is said of money that it is more easily made than kept and this is true of many things, such as friendship; and even life itself is more easily got than kept.

- Colour

- Often paraphrased as "Friendship is like money, easier made than kept."

Part X - The Position of a HomoUnius Libri

[edit]

- I doubt whether any angel would find me very entertaining. As for myself, if ever I do entertain one it will have to be unawares. When people entertain others without an introduction they generally turn out more like devils than angels.

- Entertaining Angels

- People say that there are neither dragons to be killed nor distressed maidens to be rescued nowadays. I do not know, but I think I have dropped across one or two, nor do I feel sure whether the most mortal wounds have been inflicted by the dragons or by myself.

- Dragons

- There are some things which it is madness not to try to know but which it is almost as much madness to try to know.

- Trying to Know

- He who would propagate an opinion must begin by making sure of his ground and holding it firmly. There is as little use in trying to breed from weak opinion as from other weak stock.

- The Art of Propagating Opinion

- Ideas and opinions, like living organisms, have a normal rate of growth which cannot be either checked or forced beyond a certain point. They can be held in check more safely than they can be hurried. They can also be killed; and one of the surest ways to kill them is to try to hurry them.

- The Art of Propagating Opinion

- The more unpopular an opinion is, the more necessary is it that the holder should be somewhat punctilious in his observance of conventionalities generally, and that, if possible, he should get the reputation of being well-to-do in the world.

- The Art of Propagating Opinion

- Many, if not most, good ideas die young — mainly from neglect on the part of the parents, but sometimes from over-fondness. Once well started, an opinion had better be left to shift for itself.

- The Art of Propagating Opinion

- Argument is generally waste of time and trouble. It is better to present one's opinion and leave it to stick or no as it may happen. If sound, it will probably in the end stick, and the sticking is the main thing.

- Argument

Part XI - Cash and Credit

[edit]- He [the Philosopher] should have made many mistakes and been saved often by the skin of his teeth, for the skin of one's teeth is the most teaching thing about one. He should have been, or at any rate believed himself, a great fool and a great criminal. He should have cut himself adrift from society, and yet not be without society.

- The Philosopher

- Most artists, whether in religion, music, literature, painting, or what not, are shopkeepers in disguise. They hide their shop as much as they can, and keep pretending that it does not exist, but they are essentially shopkeepers and nothing else.

- The Artist and the Shopkeeper

- It is curious that money, which is the most valuable thing in life, exceptis excipiendis, should be the most fatal corrupter of music, literature, painting and all the arts. As soon as any art is pursued with a view to money, then farewell, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, all hope of genuine good work.

- Money

- Genius...has been defined as a supreme capacity for taking trouble...It might be more fitly described as a supreme capacity for getting its possessors into trouble of all kinds and keeping them therein so long as the genius remains.

- Genius, i

- Inspiration is never genuine if it is known as inspiration at the time. True inspiration always steals on a person; its importance not being fully recognised for some time.

- Genius, iii

- Dullness is so much stronger than genius because there is so much more of it, and it is better organised and more naturally cohesive.

- Genius, iv

- All men can do great things, if they know what great things are.

- Great Things

- Surely the glory of finally getting rid of and burying a long and troublesome matter should be as great as that of making an important discovery. The trouble is that the coverer is like Samson who perished in the wreck of what he had destroyed; if he gets rid of a thing effectually he gets rid of himself too.

- The Art of Covery

- The supposition that the world is ever in league to put a man down is childish. Hardly less childish is it for an author to lay the blame on reviewers. A good sturdy author is a match for a hundred reviewers.

- Ephemeral and Permanent Success

Part XII - The Enfant Terrible of Literature

[edit]- I am the enfant terrible of literature and science.

- Myself

- If people like being deceived — and this can hardly be doubted — there can rarely have been a time during which they can have had more of the wish than now. The literary, scientific and religious worlds vie with one another in trying to gratify the public.

- Populus Vult

- The greatest poets never write poetry. The Homers and Shakespeares are not the greatest — they are only the greatest that we can know. And so with Handel among musicians. For the highest poetry, whether in music or literature, is ineffable — it must be felt from one person to another, it cannot be articulated.

- Poetry

- If a person would understand either the Odyssey or any other ancient work, he must never look at the dead without seeing the living in them, nor at the living without thinking of the dead. We are too fond of seeing the ancients as one thing and the moderns as another.

- Ancient Work

Part XIII - Unprofessional Sermons

[edit]- Nothing will ever die so long as it knows what to do under the circumstances, in other words so long as it knows its business.

- The Roman Empire

- Italians, and perhaps Frenchmen, consider first whether they like or want to do a thing and then whether, on the whole, it will do them any harm. Englishmen, and perhaps Germans, consider first whether they ought to like a thing and often never reach the questions whether they do like it and whether it will hurt. There is much to be said for both systems, but I suppose it is best to combine them as far as possible.

- Italians and Englishmen

- One can bring no greater reproach against a man than to say that he does not set sufficient value upon pleasure, and there is no greater sign of a fool than the thinking that he can tell at once and easily what it is that pleases him. To know this is not easy, and how to extend our knowledge of it is the highest and the most neglected of all arts and branches of education.

- On Knowing what Gives us Pleasure, i

- I should like to like Schumann's music better than I do; I dare say I could make myself like it better if I tried; but I do not like having to try to make myself like things; I like things that make me like them at once and no trying at all.

- On Knowing what Gives us Pleasure, ii

Part XIV - Higgledy-Piggledy

[edit]

- Every one should keep a mental waste-paper basket and the older he grows the more things he will consign to it — torn up to irrecoverable tatters.

- Waste-Paper Baskets

- They [my thoughts] are like persons met upon a journey; I think them very agreeable at first but soon find, as a rule, that I am tired of them.

- My Thoughts

- An idea must not be condemned for being a little shy and incoherent; all new ideas are shy when introduced first among our old ones. We should have patience and see whether the incoherency is likely to wear off or to wear on, in which latter case the sooner we get rid of them the better.

- Incoherency of New Ideas

- It must be remembered that we have only heard one side of the case. God has written all the books.

- An Apology for the Devil

- It does not matter much what a man hates provided he hates something.

- Hating

- The great characters of fiction live as truly as the memories of dead men. For the life after death it is not necessary that a man or woman should have lived.

- Hamlet, Don Quixote, Mr. Pickwick and others

- The evil that men do lives after them. Yes, and a good deal of the evil that they never did as well.

- Reputation

- There are two classes, those who want to know and do not care whether others think they know or not, and those who do not much care about knowing but care very greatly about being reputed as knowing.

- Scientists

- Everything matters more than we think it does, and, at the same time, nothing matters so much as we think it does. The merest spark may set all Europe in a blaze, but though all Europe be set in a blaze twenty times over, the world will wag itself right again.

- Sparks

- Time is the only true purgatory.

- Purgatory

- He is greatest who is most often in men's good thoughts.

- Greatness

- The great pleasure of a dog is that you may make a fool of yourself with him and not only will he not scold you, but he will make a fool of himself too.

- Dogs

- The Will-be and the Has-been touch us more nearly than the Is. So we are more tender towards children and old people than to those who are in the prime of life.

- Future and Past

- People are lucky and unlucky not according to what they get absolutely, but according to the ratio between what they get and what they have been led to expect.

- Lucky and Unlucky

- A definition is the enclosing a wilderness of idea within a wall of words.

- Definitions, iii

- The dons are too busy educating the young men to be able to teach them anything.

- Oxford and Cambridge

- Silence is not always tact and it is tact that is golden, not silence.

- Silence and Tact

- To put one's trust in God is only a longer way of saying that one will chance it.

- Providence and Improvidence, ii

- To live is like to love — all reason is against it, and all healthy instinct for it.

- Life and Love

Part XV - Titles and Subjects

[edit]- This poem [The Ancient Mariner] would not have taken so well if it had been called “The Old Sailor.”

- The Ancient Mariner

Part XVI - Written Sketches

[edit]- A little boy and a little girl were looking at a picture of Adam and Eve. "Which is Adam and which is Eve?" said one. "I do not know," said the other, "but I could tell if they had their clothes on."

- Adam and Eve

Part XVII - Material for a Projected Sequel to Alps and Sanctuaries

[edit]- The public buys its opinions as it buys its meat, or takes in its milk, on the principle that it is cheaper to do this than to keep a cow. So it is, but the milk is more likely to be watered.

- Public Opinions

- Men are seldom more commonplace than on supreme occasions.

- Supreme Occasions

Part XIX - Truth and Convenience

[edit]- The pursuit of truth is chimerical. That is why it is so hard to say what truth is. There is no permanent absolute unchangeable truth; what we should pursue is the most convenient arrangement of our ideas.

- Truth, ii

- Some men love truth so much that they seem to be in continual fear lest she should catch cold on over-exposure.

- Truth, vii

- Truth consists not in never lying but in knowing when to lie and when not to do so.

- Falsehood, i

- Any fool can tell the truth, but it requires a man of some sense to know how to lie well.

- Falsehood, iii

- I do not mind lying, but I hate inaccuracy.

- Falsehood, iv

Part XX - First Principles

[edit]- Our choice is apparently most free, and we are least obviously driven to determine our course, in those cases where the future is most obscure, that is, when the balance of advantage appears most doubtful.

- Choice

- You can have all ego, or all non-ego, but in theory you cannot have half one and half the other — yet in practice this is exactly what you must have, for everything is both itself and not itself at one and the same time.

- Ego and Non-Ego

- As a general rule philosophy is like stirring mud or not letting a sleeping dog lie. It is an attempt to deny, circumvent or otherwise escape from the consequences of the interlacing of the roots of things with one another.

- Philosophy

- It is with philosophy as with just intonation on a piano, if you get everything quite straight and on all fours in one department, in perfect tune, it is delightful so long as you keep well in the middle of the key; but as soon as you modulate you find the new key is out of tune and the more remotely you modulate the more out of tune you get.

- Philosophy and Equal Temperament

- We are not won by arguments that we can analyse, but by tone and temper, by the manner which is the man himself.

Part XXI - Rebelliousness

[edit]- You can do very little with faith, but you can do nothing without it.

- Faith, ii

Part XXII - Reconciliation

[edit]- I am not sure that I do not begin to like the correction of a mistake, even when it involves my having shown much ignorance and stupidity, as well as I like hitting on a new idea.

- Inaccuracy

Part XXIII - Death

[edit]- No one thinks he will escape death, so there is no disappointment and, as long as we know neither the when nor the how, the mere fact that we shall one day have to go does not much affect us; we do not care, even though we know vaguely that we have not long to live. The serious trouble begins when death becomes definite in time and shape. It is in precise fore-knowledge, rather than in sin, that the sting of death is to be found; and such fore-knowledge is generally withheld; though, strangely enough, many would have it if they could.

- Fore-knowledge of Death

- To die completely, a person must not only forget but be forgotten, and he who is not forgotten is not dead.

- Complete Death

- There is nothing which at once affects a man so much and so little as his own death.

- The Defeat of Death

- To himself every one is an immortal: he may know that he is going to die, but he can never know that he is dead.

- Ignorance of Death

Part XXIV - The Life of the World to Come

[edit]- To try to live in posterity is to be like an actor who leaps over the footlights and talks to the orchestra.

- Posthumous Life, i

- The world will, in the end, follow only those who have despised as well as served it.

- The World

- When I am dead I would rather people thought me better than I was instead of worse; but if they think me worse, I cannot help it and, if it matters at all, it will matter more to them than to me.

- Apologia, i

- I call it to mind and delight in it now, but I did not notice it at the time. We next to never know when we are well off: but this cuts two ways,--for if we did, we should perhaps know better when we are ill off also; and I have sometimes thought that there are as many ignorant of the one as of the other. He who wrote, “O fortunatos nimium sua si bona norint agricolas,” might have written quite as truly, “O infortunatos nimium sua si mala norint”; and there are few of us who are not protected from the keenest pain by our inability to see what it is that we have done, what we are suffering, and what we truly are. Let us be grateful to the mirror for revealing to us our appearance only.

- Ch. 3

- I felt comparatively happy, but I can assure the reader that I had had a far worse time of it than I have told him; and I strongly recommend him to remain in Europe if he can; or, at any rate, in some country which has been explored and settled, rather than go into places where others have not been before him. Exploring is delightful to look forward to and back upon, but it is not comfortable at the time, unless it be of such an easy nature as not to deserve the name.

- Ch. 4

- When he had left the room, I mused over the conversation which had just taken place between us, but I could make nothing out of it, except that it argued an even greater perversity of mental vision than I had been yet prepared for. And this made me wretched; for I cannot bear having much to do with people who think differently from myself.

- Ch. 9

- No one with any sense of self-respect will place himself on an equality in the matter of affection with those who are less lucky than himself in birth, health, money, good looks, capacity, or anything else. Indeed, that dislike and even disgust should be felt by the fortunate for the unfortunate, or at any rate for those who have been discovered to have met with any of the more serious and less familiar misfortunes, is not only natural, but desirable for any society, whether of man or brute.

- Ch. 10

- For property is robbery, but then, we are all robbers or would-be robbers together, and have found it essential to organise our thieving, as we have found it necessary to organise our lust and our revenge. Property, marriage, the law; as the bed to the river, so rule and convention to the instinct; and woe to him who tampers with the banks while the flood is flowing.

- Ch. 12

- But the main argument on which they rely is that of economy: for they know that they will sooner gain their end by appealing to men's pockets, in which they have generally something of their own, than to their heads, which contain for the most part little but borrowed or stolen property.

- Ch. 12

- It is here that almost all religions go wrong. Their priests try to make us believe that they know more about the unseen world than those whose eyes are still blinded by the seen, can ever know--forgetting that while to deny the existence of an unseen kingdom is bad, to pretend that we know more about it than its bare existence is no better.

- Ch. 15

- But I did not yield at once; I enjoyed the process of being argued with too keenly to lose it by a prompt concession; besides, a little hesitation rendered the concession itself more valuable.

- Ch. 16

- They were gentlemen in the full sense of the word; and what has one not said in saying this?

- Ch. 17

- It is a distinguishing peculiarity of the Erewhonians that when they profess themselves to be quite certain about any matter, and avow it as a base on which they are to build a system of practice, they seldom quite believe in it. If they smell a rat about the precincts of a cherished institution, they will always stop their noses to it if they can.

- Ch. 18

- Strange fate for man! He must perish if he get that, which he must perish if he strive not after. If he strive not after it he is no better than the brutes, if he get it he is more miserable than the devils.

- Ch. 19

- “To be born,” they say, “is a felony--it is a capital crime, for which sentence may be executed at any moment after the commission of the offence. You may perhaps happen to live for some seventy or eighty years, but what is that, compared with the eternity you now enjoy? And even though the sentence were commuted, and you were allowed to live on for ever, you would in time become so terribly weary of life that execution would be the greatest mercy to you.

- Ch. 19

- It is hard upon the duckling to have been hatched by a hen, but is it not also hard upon the hen to have hatched the duckling?

- Ch. 19

- No Erewhonian believes that the world is as black as it has been here painted, but it is one of their peculiarities that they very often do not believe or mean things which they profess to regard as indisputable.

- Ch. 20

- It has been said that the love of money is the root of all evil. The want of money is so quite as truly.

- Ch. 20

- Their view evidently was that genius was like offences--needs must that it come, but woe unto that man through whom it comes. A man’s business, they hold, is to think as his neighbours do, for Heaven help him if he thinks good what they count bad. And really it is hard to see how the Erewhonian theory differs from our own, for the word “idiot” only means a person who forms his opinions for himself.

- Ch. 22

- “It is not our business,” he said, “to help students to think for themselves. Surely this is the very last thing which one who wishes them well should encourage them to do. Our duty is to ensure that they shall think as we do, or at any rate, as we hold it expedient to say we do.”

- Ch. 22

- I could hardly avoid a sort of suspicion that some of those whom I was taken to see had been so long engrossed in their own study of hypothetics that they had become the exact antitheses of the Athenians in the days of St. Paul; for whereas the Athenians spent their lives in nothing save to see and to hear some new thing, there were some here who seemed to devote themselves to the avoidance of every opinion with which they were not perfectly familiar, and regarded their own brains as a sort of sanctuary, to which if an opinion had once resorted, none other was to attack it.

- Ch. 22

- We find it difficult to sympathise with the emotions of a potato; so we do with those of an oyster. Neither of these things makes a noise on being boiled or opened, and noise appeals to us more strongly than anything else, because we make so much about our own sufferings. Since, then, they do not annoy us by any expression of pain we call them emotionless; and so qua mankind they are; but mankind is not everybody.

- Ch. 23

- “If it be urged that the action of the potato is chemical and mechanical only, and that it is due to the chemical and mechanical effects of light and heat, the answer would seem to lie in an inquiry whether every sensation is not chemical and mechanical in its operation? whether those things which we deem most purely spiritual are anything but disturbances of equilibrium in an infinite series of levers, beginning with those that are too small for microscopic detection, and going up to the human arm and the appliances which it makes use of? whether there be not a molecular action of thought, whence a dynamical theory of the passions shall be deducible? Whether strictly speaking we should not ask what kind of levers a man is made of rather than what is his temperament? How are they balanced? How much of such and such will it take to weigh them down so as to make him do so and so?”

- Ch. 23

- “Silence,” it has been said by one writer, “is a virtue which renders us agreeable to our fellow-creatures.”

- Ch. 23

- A man is the resultant and exponent of all the forces that have been brought to bear upon him, whether before his birth or afterwards. His action at any moment depends solely upon his constitution, and on the intensity and direction of the various agencies to which he is, and has been, subjected. Some of these will counteract each other; but as he is by nature, and as he has been acted on, and is now acted on from without, so will he do, as certainly and regularly as though he were a machine.

We do not generally admit this, because we do not know the whole nature of any one, nor the whole of the forces that act upon him. We see but a part, and being thus unable to generalise human conduct, except very roughly, we deny that it is subject to any fixed laws at all, and ascribe much both of a man's character and actions to chance, or luck, or fortune; but these are only words whereby we escape the admission of our own ignorance; and a little reflection will teach us that the most daring flight of the imagination or the most subtle exercise of the reason is as much the thing that must arise, and the only thing that can by any possibility arise, at the moment of its arising, as the falling of a dead leaf when the wind shakes it from the tree.- Ch. 25

- And should we not be guilty of consummate folly if we were to reject advantages which we cannot obtain otherwise, merely because they involve a greater gain to others than to ourselves?

- Ch. 25

- Happily common sense, though she is by nature the gentlest creature living, when she feels the knife at her throat, is apt to develop unexpected powers of resistance, and to send doctrinaires flying, even when they have bound her down and think they have her at their mercy.

- Ch. 26

- As a matter of course, the basis on which he decided that duty could alone rest was one that afforded no standing-room for many of the old-established habits of the people. These, he assured them, were all wrong, and whenever any one ventured to differ from him, he referred the matter to the unseen power with which he alone was in direct communication, and the unseen power invariably assured him that he was right.

- Ch. 26

- “Plants,” said he, "show no sign of interesting themselves in human affairs. We shall never get a rose to understand that five times seven are thirty-five, and there is no use in talking to an oak about fluctuations in the price of stocks. Hence we say that the oak and the rose are unintelligent, and on finding that they do not understand our business conclude that they do not understand their own. But what can a creature who talks in this way know about intelligence? Which shows greater signs of intelligence? He, or the rose and oak?

- Ch. 27

- But so engrained in the human heart is the desire to believe that some people really do know what they say they know, and can thus save them from the trouble of thinking for themselves, that in a short time would-be philosophers and faddists became more powerful than ever, and gradually led their countrymen to accept all those absurd views of life.

- Ch. 27

The Way of All Flesh (1903)

[edit]- It is far safer to know too little than too much. People will condemn the one, though they will resent being called upon to exert themselves to follow the other.

- Ch. 5

- Adversity, if a man is set down to it by degrees, is more supportable with equanimity by most people than any great prosperity arrived at in a single lifetime.

- Ch. 5

- We know so well what we are doing ourselves and why we do it, do we not? I fancy that there is some truth in the view which is being put forward nowadays, that it is our less conscious thoughts and our less conscious actions which mainly mould our lives and the lives of those who spring from us.

- Ch. 5

- Youth is like spring, an overpraised season.

- Ch. 6

- A pair of lovers are like sunset and sunrise: there are such things every day but we very seldom see them.

- Ch. 11

- Taking numbers into account, I should think more mental suffering had been undergone in the streets leading from St George's, Hanover Square, than in the condemned cells of Newgate.

- Ch. 13

- Every man's work, whether it be literature or music or pictures or architecture or anything else, is always a portrait of himself, and the more he tries to conceal himself the more clearly will his character appear in spite of him.

- Ch. 14

- How is it, I wonder, that all religious officials, from God the Father to the parish beadle, should be so arbitrary and exacting.

- Ch. 23; this is one of the passages excised from The Way of All Flesh when it was first published in 1903, after Butler's death, by his literary executor, R. Streatfeild. This first edition of The Way of All Flesh is widely available in plain text on the internet, but readers of facsimiles of the first edition should be aware that Streatfeild significantly altered and edited Butler's text, "regularizing" the punctuation and removing most of Butler's most trenchant criticism of Victorian society and conventional pieties. Butler's full manuscript, entitled Ernest Pontifex, or The Way of All Flesh, was edited and issued by Daniel F. Howard in 1965. It is from this edition that this quote is derived; it was excised by Streatfeild in the first edition.

- One great reason why clergymen's households are generally unhappy is because the clergyman is so much at home or close about the house.

- Ch. 24

- Sensible people get the greater part of their own dying done during their own lifetime.

- Ch. 24

- To me it seems that those who are happy in this world are better and more lovable people than those who are not.

- Ch. 26

- There are two classes of people in this world, those who sin, and those who are sinned against; if a man must belong to either, he had better belong to the first than to the second.

- Ch. 26

- The advantage of doing one's praising for oneself is that one can lay it on so thick and exactly in the right places.

- Ch. 34

- The best liar is he who makes the smallest amount of lying go the longest way.

- A man can stand being told that he must submit to a severe surgical operation, or that he has some disease which will shortly kill him, or that he will be a cripple or blind for the rest of his life; dreadful as such tidings must be, we do not find that they unnerve the greatest number of mankind; most men, indeed, go coolly enough even to be hanged, but the strongest quail before financial ruin, and the better men they are, the more complete, as a general rule, is their prostration.

- Ch. 66

- As the days went slowly by he came to see that Christianity and the denial of Christianity after all met as much as any other extremes do; it was a fight about names — not about things; practically the Church of Rome, the Church of England, and the freethinker have the same ideal standard and meet in the gentleman; for he is the most perfect saint who is the most perfect gentleman. Then he saw also that it matters little what profession, whether of religion or irreligion, a man may make, provided only he follows it out with charitable inconsistency, and without insisting on it to the bitter end. It is in the uncompromisingness with which dogma is held and not in the dogma or want of dogma that the danger lies.

- An empty house is like a stray dog or a body from which life has departed.

- Ch. 72

- A man's friendships are, like his will, invalidated by marriage—but they are also no less invalidated by the marriage of his friends.

- Ch. 75

External links

[edit]- Works by Samuel Butler at Project Gutenberg

- Erewhon at Project Gutenberg

- Erewhon Revisited at Project Gutenberg