Freedom of speech: Difference between revisions

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Content deleted Content added

-redundant category/subcategory |

add img 1791 |

||

| (84 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Free-speech-flag.svg|thumb|{{w|Free Speech Flag}}]] |

|||

'''[[w:Freedom of speech|Freedom of speech]]''' is the concept of being able to speak freely without censorship. It is often regarded as an integral concept in modern liberal democracies. |

|||

'''[[w:Freedom of speech|Freedom of speech]]''' is the concept of being able to speak freely without [[censorship]]. It is often regarded as an integral concept in modern liberal democracies. |

|||

{{theme-cleanup|2008-03-27}} |

|||

== Sourced == |

== Sourced == |

||

*All Ministers ... who were Oppressors, or intended to be Oppressors, have been loud in their Complaints against Freedom of Speech, and the License of the Press; and always restrained, or endeavored to restrain, both. |

|||

**{{w|Cato's Letters}}, [[w:John Trenchard (writer)|John Trenchard]] and [[w:Thomas Gordon (writer)|Thomas Gordon]] (Letter Number 15, ''Of Freedom of Speech, That the Same is inseparable from Publick Liberty'', February 4, 1720). |

|||

*The liberty of the press is the birthright of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country. It has been the terror of all bad ministers; for their dark and dangerous designs, of their weakness, inability, and duplicity, have thus been detected and shown to the public, generally in too strong and just colors for them to bear up against the odium of mankind. ... A wicked and corrupt administration must naturally dread this appeal to the world; and will be for keeping all the means of information from the prince, parliament, and people. |

|||

**{{w|John Wilkes}}, (''[[w:The North Briton|The North Briton]]'', No. 1. June 5, 1762). |

|||

[[File:Sir William Blackstone from NPG.jpg|thumb|{{w|William Blackstone}}]] |

|||

*The liberty of the press ... consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his own temerity. |

|||

**{{w|William Blackstone}}, (''{{w|Commentaries on the Laws of England}}'', 1765-1769). |

|||

*There is nothing so ''fretting'' and ''vexatious'', nothing so justly TERRIBLE to tyrants, and their tools and abettors, as a FREE PRESS. |

|||

**{{w|Samuel Adams}}, (''{{w|Boston Gazette}}'', 1768) — cited in: {{cite book|page=61|first=Jonathan W.|last=Emord|title=Freedom, Technology, and the First Amendment|year=1991|publisher=Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy}} |

|||

*The liberty of the press is essential to the security of freedom in a state: it ought not, therefore, to be restrained in this commonwealth. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[John Adams]], [[Samuel Adams]], {{w|James Bowdoin}}|title=[[w:Massachusetts Constitution|Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts]]|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts|Commonwealth of Massachusetts]]|location=|year=1780|pages= Article XVI|isbn=|oclc=|doi=}}[[s:Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1780)|Text]] |

|||

*Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter. |

|||

**[[Thomas Jefferson]] to Edward Carrington, January 16, 1787, ''The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827'' ([[w:Library of Congress|Library of Congress]]). |

|||

*I confess I do not see in what cases the Congress can, with any pretence of right, make a law to supress the freedom of the press; though I am not clear, that Congress is restrained from laying any duties whatever on certain pieces printed, and perhaps Congress may require large bonds for the payment of these duties. Should the printer say, the freedom of the press was secured by teh constitution of the state in which he lived, Congress might, and perhaps, with great propriety, answer, that the federal constitution is the only compact existing between them and the people; in this compact the people have named no others, and therefore Congress, in exercising the powers assigned them, and in making laws to carry them into execution are restrained by nothing beside the federal constitution. |

|||

**{{w|Richard Henry Lee}}, (''[[w:The Federal Farmer|The Federal Farmer]]'', 4th letter, October 15, 1787). — cited in: {{cite book|pages=75-76|first=Jonathan W.|last=Emord|title=Freedom, Technology, and the First Amendment|year=1991|publisher=Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy}} |

|||

* Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. |

* Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. |

||

** [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution]]. |

** [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution]]. December 15, 1791. |

||

[[File:Thomas Jefferson rev.jpg|thumb|[[Thomas Jefferson]] (1791)]] |

|||

* I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it. |

* I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it. |

||

** To Archibald Stuart, Philadelphia, |

** To Archibald Stuart, Philadelphia, December 23, 1791. |

||

** Cited in {{cite book |author=Thomas Jefferson|authorlink=Thomas Jefferson | editor = Jerry Holmes | title = Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=iOHNKGJGo94C&pg=PA128&dq=%22too+much+liberty%22+0742521168&sig=kwr0H-XgcHnnQiMeH4PARcN0D_4 | year = 2002 | publisher = Rowman & Littlefield | id = ISBN 0742521168 | pages = p. 128 | chapter = 1791}} |

|||

** Cited in {{cite book |

|||

| last = Jefferson |

|||

* The power of communication of thoughts and opinions is the gift of God, and the freedom of it is the source of all science, the first fruits and the ultimate happiness of society; and therefore it seems to follow, that human laws ought not to interpose, nay, cannot interpose, to prevent the communication of sentiments and opinions in voluntary assemblies of men. |

|||

| first = Thomas |

|||

** Eyre, L.C.J., Hardy's Case (1794), 24 How. St. Tr. 206; reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, ''The Dictionary of Legal Quotations'' (1904), p. 99. |

|||

| editor = Jerry Holmes |

|||

| title = Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=iOHNKGJGo94C&pg=PA128&dq=%22too+much+liberty%22+0742521168&sig=kwr0H-XgcHnnQiMeH4PARcN0D_4 |

|||

| year = 2002 |

|||

| publisher = Rowman & Littlefield |

|||

| id = ISBN 0742521168 |

|||

| pages = p. 128 |

|||

| chapter = 1791 |

|||

}} |

|||

* Error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it. |

* Error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it. |

||

** [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[s:Thomas Jefferson's First Inaugural Address|First Inaugural Address]], |

** [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[s:Thomas Jefferson's First Inaugural Address|First Inaugural Address]], March 4, 1801. |

||

*The diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason; freedom of religion; freedom of the press, and freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus, and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety. |

|||

* After all, if freedom of speech means anything, it means a willingness to stand and let people say things with which we disagree, and which do weary us considerably. |

|||

** [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[s:Thomas Jefferson's First Inaugural Address|First Inaugural Address]], March 4, 1801. |

|||

** Zechariah Chafee; in {{cite book |

|||

| last = Chafee |

|||

*May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. |

|||

| title = Freedom of Speech |

|||

**[[Thomas Jefferson]], Letter to Roger Weightman, June 24, 1826, in ''The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson'', ed. Adrienne Koch and William Peden (New York: Modern Library, 1944), p. 729. |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=XuQ9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA366&dq=%22freedom+of+speech+means+anything%22&lr= |

|||

| year = 1920 |

|||

| publisher = Harcourt, Brace and Howe |

|||

| pages = p. 366 |

|||

}} |

|||

* How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech. |

* How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech. |

||

** [[Soren Kierkegaard]] ''Either/Or Part I'', Swenson p. 19. |

** [[Soren Kierkegaard]] ''Either/Or Part I'' (1843), Swenson p. 19. |

||

* And I honor the man who is willing to sink <br /> Half his present repute for the freedom to think, <br /> And, when he has thought, be his cause strong or weak, <br /> Will risk t'other half for the freedom to speak. |

* And I honor the man who is willing to sink <br /> Half his present repute for the freedom to think, <br /> And, when he has thought, be his cause strong or weak, <br /> Will risk t'other half for the freedom to speak. |

||

** [[James Russell Lowell]], ''A Fable for Critics'' (1848), Pt. V - ''Cooper'', st. 3. |

** [[James Russell Lowell]], ''A Fable for Critics'' (1848), Pt. V - ''Cooper'', st. 3. |

||

*No law shall be passed restraining the free expression of opinion, or restricting the right to speak, write or print freely on any subject whatever. |

|||

* I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it. |

|||

**''{{w|Oregon Constitution}}'', (1857), Article I, Section 8. |

|||

** [[Evelyn Beatrice Hall]], Ch. 7 : Helvetius : The Contradiction, p. 199. |

|||

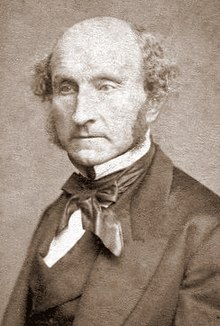

[[File:John Stuart Mill by John Watkins, 1865.jpg|thumb|[[John Stuart Mill]]]] |

|||

*Strange it is that men should admit the validity of the arguments for free speech but object to their being "pushed to an extreme", not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case. |

*Strange it is that men should admit the validity of the arguments for free speech but object to their being "pushed to an extreme", not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case. |

||

**[[John Stuart Mill]], 'On Liberty' Ch. 2, {{cite book |

**[[John Stuart Mill]], ''On Liberty'' (1859) Ch. 2, {{cite book | last = Mill | title = On Liberty | url = | year = 1985 | publisher = Penguin | pages = p. 108}} |

||

| last = Mill |

|||

| title = On Liberty |

|||

| url = |

|||

| year = 1985 |

|||

| publisher = Penguin |

|||

| pages = p. 108 |

|||

}} |

|||

*If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. ... Though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied ... Even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension [of] or feeling [for] its rational grounds. |

|||

* The power of communication of thoughts and opinions is the gift of God, and the freedom of it is the source of all science, the first fruits and the ultimate happiness of society; and therefore it seems to follow, that human laws ought not to interpose, nay, cannot interpose, to prevent the communication of sentiments and opinions in voluntary assemblies of men. |

|||

**[[John Stuart Mill]], ''{{w|On Liberty}}'', (1859). |

|||

** Eyre, L.C.J., Hardy's Case (1794), 24 How. St. Tr. 206; reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, ''The Dictionary of Legal Quotations'' (1904), p. 99. |

|||

* I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it. |

|||

** [[Evelyn Beatrice Hall]], Ch. 7 : ''[[w:The Friends of Voltaire|Helvetius: The Contradiction]]'' (1906), p. 199. |

|||

*The general rule of law is, that the noblest of human productions — knowledge, truths ascertained, conceptions and ideas — become, after voluntary communication to others, free as the air to common use. |

|||

**{{w|Louis Brandeis}}, (''{{w|International News Service v. Associated Press}}'', 1918). |

|||

*When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution. |

|||

**{{w|Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.}}, (''{{w|Abrams v. United States}}'', 1919). |

|||

* After all, if freedom of speech means anything, it means a willingness to stand and let people say things with which we disagree, and which do weary us considerably. |

|||

** [[Zechariah Chafee]]; in {{cite book | last = Chafee | title = Freedom of Speech | url = http://books.google.com/books?id=XuQ9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA366&dq=%22freedom+of+speech+means+anything%22&lr= | year = 1920 | publisher = Harcourt, Brace and Howe | pages = p. 366}} |

|||

*It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears. |

|||

**{{w|Louis Brandeis}}, (''{{w|Whitney v. California}}'', 1927). |

|||

*Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties; and that in its government the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government. |

|||

**{{w|Louis Brandeis}}, (''{{w|Whitney v. California}}'', 1927). |

|||

*Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present, unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence. |

|||

**{{w|Louis Brandeis}}, (''{{w|Whitney v. California}}'', 1927). |

|||

[[File:Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr circa 1930.jpg|thumb|{{w|Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.}}]] |

|||

*If there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought we hate. |

|||

**{{w|Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.}}, (''[[w:United States v. Schwimmer|United States v. Schwimmer]]'', 1929). |

|||

*The exceptional nature of its limitations places in a strong light the general conception that liberty of the press, historically considered and taken up by the Federal Constitution, has meant, principally, although not exclusively, immunity from previous restraints or censorship. |

|||

**{{w|Charles Evans Hughes}}, (''{{w|Near v. Minnesota}}'', 1931). |

|||

*It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press, and of speech, is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action. It was found impossible to conclude that this essential personal liberty of the citizen was left unprotected by the general guaranty of fundamental rights of person and property. |

|||

**{{w|Charles Evans Hughes}}, (''{{w|Near v. Minnesota}}'', 1931). |

|||

*The liberty of the press is not confined to newspapers and periodicals. It necessarily embraces pamphlets and leaflets. ... the press in its historic connotation comprehends every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion. |

|||

**{{w|Charles Evans Hughes}}, (''{{w|Lovell v. City of Griffin}}'', 1938). |

|||

*The freedom of speech and of the press, which are secured by the First Amendment against abridgment by the United States, are among the fundamental personal rights and liberties which are secured to all persons by the Fourteenth Amendment against abridgment by a state. The safeguarding of these rights to the ends that men may speak as they think on matters vital to them and that falsehoods may be exposed through the processes of education and discussion is essential to free government. Those who won our independence had confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning and communication of ideas to discover and spread political and economic truth. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[w:Frank Murphy|Frank Murphy]]|title=[[w:Thornhill v. Alabama|Thornhill v. Alabama]]|publisher=[[Supreme Court of the United States]]|location=|year=1940|pages= 310 U.S. 88, 95|isbn=|oclc=|doi=}} |

|||

*Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Robert H. Jackson]]|title={{w|West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette}}|publisher=[[Supreme Court of the United States]]|location=|year=1943|pages= 319 U.S. 624, 638|isbn=|oclc=|doi=}} |

|||

*The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities, and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. / One's right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Robert H. Jackson]]|title={{w|West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette}}|publisher=[[Supreme Court of the United States]]|location=|year=1943|pages= 319 U.S. 624, 638|isbn=|oclc=|doi=}} |

|||

*Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. |

|||

**{{cite book |

|||

|author={{w|United Nations General Assembly}}|title={{w|Universal Declaration of Human Rights}}|publisher=[[United Nations]]|location={{w|Palais de Chaillot}}, [[w:Paris|Paris]]|year=December 10, 1948|pages= Article 19|isbn=|oclc=|doi=}}[http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html Text] |

|||

*That there is a social problem presented by obscenity is attested by the expression of the legislatures of the forty-eight States, as well as the Congress. To recognize the existence of a problem, however, does not require that we sustain any and all measures adopted to meet that problem. The history of the application of laws designed to suppress the obscene demonstrates convincingly that the power of government can be invoked under them against great art or literature, scientific treatises, or works exciting social controversy. Mistakes of the past prove that there is a strong countervailing interest to be considered in the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. |

|||

**{{w|Earl Warren}}, [[w:Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice of the United States]] (''[[w:Roth v. United States|Roth v. United States]]'', 1957). |

|||

*If the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech and press is to mean anything, it must allow protests even against the moral code that the standard of the day sets for the community. |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, {{w|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States}} (''{{w|Roth v. United States}}'', 1957). |

|||

*The standard of what offends 'the common conscience of the community' conflicts ... with the command of the First Amendment. ... Certainly that standard would not be an acceptable one if religion, economics, politics or philosophy were involved. How does it become a constitutional standard when literature treating with sex is concerned? / Any test that turns on what is offensive to the community's standards is too loose, too capricious, too destructive of freedom of expression to be squared with the First Amendment. Under that test, juries can censor, suppress, and punish what they don't like, provided the matter relates to 'sexual impurity' or has a tendency to 'excite lustful thoughts.' This is community censorship in one of its worst forms... |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, {{w|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States}} (''{{w|Roth v. United States}}'', 1957). |

|||

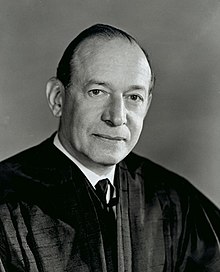

[[File:US Supreme Court Justice William Brennan - 1976 official portrait.jpg|thumb|{{w|William J. Brennan, Jr.}}]] |

|||

*We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a State's power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct. |

|||

**{{w|William J. Brennan, Jr.}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[New York Times Co. v. Sullivan]]'', 1964). |

|||

*[There exists a] profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials. |

|||

**{{w|William J. Brennan, Jr.}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[New York Times Co. v. Sullivan]]'', 1964). |

|||

*Authoritative interpretations of the First Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth — whether administered by judges, juries, or administrative officials — and especially one that puts the burden of proving truth on the speaker. |

|||

**{{w|William J. Brennan, Jr.}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[New York Times Co. v. Sullivan]]'', 1964). |

|||

*I think the conviction of appellant or anyone else for exhibiting a motion picture abridges freedom of the press as safeguarded by the First Amendment, which is made obligatory on the States by the Fourteenth. |

|||

**{{w|Hugo Black}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[w:Jacobellis v. Ohio|Jacobellis v. Ohio]]'', 1964). |

|||

*The censor is always quick to justify his function in terms that are protective of society. But the First Amendment, written in terms that are absolute, deprives the States of any power to pass on the value, the propriety, or the morality of a particular expression. |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[w:Memoirs v. Massachusetts|Memoirs v. Massachusetts]]'', 1966). |

|||

*The dissemination of the individual's opinions on matters of public interest is for us, in the historic words of the Declaration of Independence, an 'unalienable right' that 'governments are instituted among men to secure.' History shows us that the Founders were not always convinced that unlimited discussion of public issues would be 'for the benefit of all of us' but that they firmly adhered to the proposition that the 'true liberty of the press' permitted 'every man to publish his opinion'. |

|||

**{{w|John Marshall Harlan II}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[w:Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts|Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts]]'', 1967). |

|||

*Whatever may be the justifications for other statutes regulating obscenity, we do not think they reach into the privacy of one's own home. If the First Amendmen means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men's minds. |

|||

**{{w|Thurgood Marshall}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''[[w:Stanley v. Georgia|Stanley v. Georgia]]'', 1969). |

|||

[[File:SCOTUS Justice Abe Fortas.jpeg|thumb|{{w|Abe Fortas}}]] |

|||

*First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate. |

|||

**{{w|Abe Fortas}}, (''{{w|Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District}}'', 1969). |

|||

*In order for the State in the person of school officials to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, it must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint. |

|||

**{{w|Abe Fortas}}, (''{{w|Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District}}'', 1969). |

|||

*Under our Constitution, free speech is not a right that is given only to be so circumscribed that it exists in principle but not in fact. Freedom of expression would not truly exist if the right could be exercised only in an area that a benevolent government has provided as a safe haven for crackpots. The Constitution says that Congress (and the States) may not abridge the right to free speech. This provision means what it says. We properly read it to permit reasonable regulation of speech-connected activities in carefully restricted circumstances. But we do not confine the permissible exercise of First Amendment rights to a telephone booth or the four corners of a pamphlet, or to supervised and ordained discussion in a school classroom. |

|||

**{{w|Abe Fortas}}, (''{{w|Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District}}'', 1969). |

|||

*... I would not in this case decide, even by way of dicta, that the Government may lawfully seize literary material intended for the purely private use of the importer. The terms of the statute appear to apply to an American tourist who, after exercising his constitutionally protected liberty to travel abroad, returns home with a single book in his luggage, with no intention of selling it or otherwise using it, except to read it. If the Government can constitutionally take the book away from him as he passes through customs, then I do not understand the meaning of ''{{w|Stanley v. Georgia}}''. |

|||

**{{w|Potter Stewart}}, [[w:Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] (''{{w|United States v. Thirty-Seven Photographs}}'', 1971). |

|||

*In the First Amendment, the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection is must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government's power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. |

|||

**{{w|Hugo L. Black}}, (''{{w|New York Times Company v. United States}}'', 1971). |

|||

*Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. |

|||

**{{w|Hugo L. Black}}, (''{{w|New York Times Company v. United States}}'', 1971). |

|||

*The word "security" is a broad, vague generality whose contours should not be invoked to abrogate the fundamental law embodied in the First Amendment. The guarding of military and diplomatic secrets at the expense of informed representative government provides no real security four our Republic. |

|||

**{{w|Hugo L. Black}}, (''{{w|New York Times Company v. United States}}'', 1971). |

|||

*Effective self-government cannot succeed unless the people are immersed in a steady, robust, unimpeded, and uncensored flow of opinion and reporting which are continuously subjected to critique, rebuttal, and reexamination. |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, (''{{w|Branzburg v. Hayes}}'', 1972). |

|||

*The people, the ultimate governors, must have absolute freedom of, and therefore privacy of, their individual opinions and beliefs regardless of how suspect or strange they may appear to others. Ancillary to that principle is the conclusion that an individual must also have absolute privacy over whatever information he may generate in the course of testing his opinions and beliefs. |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, (''{{w|Branzburg v. Hayes}}'', 1972). |

|||

*It is my view that there is no "compelling need" that can be shown which qualifies the reporter's immunity from appearing or testifying before a grand jury, unless the reporter himself is implicated in a crime. His immunity, in my view, is therefore quite complete, for, absent his involvement in a crime, the First Amendment protects him against an appearance before a grand jury, and, if he is involved in a crime, the Fifth Amendment stands as as a barrier. ... And since, in my view, a newsman has an absolute right not to appear before a grand jury, it follows for me that a journalist who voluntarily appears before that body may invoke his First Amendment privilege to specific questions. |

|||

**{{w|William O. Douglas}}, (''{{w|Branzburg v. Hayes}}'', 1972). |

|||

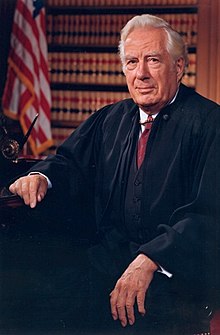

[[File:Warren e burger photo.jpeg|thumb|{{w|Warren E. Burger}}]] |

|||

*Prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and least tolerable infringement on First Amendment Rights. |

|||

**{{w|Warren E. Burger}}, [[w:Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice of the United States]] (''[[w:Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart|Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart]]'', 1976). |

|||

*We conclude that public figures and public officials may not recover for the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress by reason of publications such as the one here at issue without showing, in addition, that the publication contains a false statement of fact which was made with 'actual malice,' i.e., with knowledge that the statement was false or with reckless disregard as to whether or not it was true. This is not merely a 'blind application' of the New York Times standard, see Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374, 390 (1967); it reflects our considered judgment that such a standard is necessary to give adequate "breathing space" to the freedoms protected by the First Amendment. |

|||

**{{w|William Rehnquist}}, [[w:Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice of the United States]] (''[[Hustler Magazine v. Falwell]]'', 1988). |

|||

*There is no indication - either in the text of the Constitution or in our cases interpreting it - that a separate judicial category exists for the American flag alone. ... We decline ... therefore to create for the flag an exception to the joust of principles protected by the First Amendment. |

|||

**{{w|William J. Brennan, Jr.}}, {{w|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States}} (''{{w|Texas v. Gregory Lee Johnson}}'', June 21, 1989). |

|||

*I rise today to support the efforts of citizens everywhere to protect free speech on the Internet. Today, the Supreme Court heard arguments to determine the constitutionality of the Communications Decency Act [CDA], which criminalizes certain speech on the Internet. It is because of the hard work and dedication to free speech by netizens everywhere that this issue has gained the attention of the public, and now, our Nation's highest court. I have maintained from the very beginning that the CDA is unconstitutional, and I eagerly await the Supreme Court's decision on this case. |

|||

**{{w|Jerrold Nadler}}, {{w|United States House of Representatives}} ([[s:Free Speech on the Internet|"Free Speech on the Internet"]], ''{{w|Congressional Record}}'', March 19, 1997). |

|||

*One question that remains is at what point an individual Net poster has the right to assume prerogatives that have traditionally been only the province of journalists and news-gathering organizations. When the Pentagon Papers landed on the doorstep of the ''New York Times'', the newspaper was able to publish under the First Amendment's guarantees of freedom of speech, and to make a strong argument in court that publication was in the public interest. ... the amplification inherent in the combination of the Net's high-speed communications and the size of the available population has greatly changed the balance of power. |

|||

**{{cite book|title=[[w:Net.wars|Net.wars]]|author=[[w:Wendy M. Grossman|Wendy M. Grossman]]|page=90|publisher=[[w:New York University|New York University Press]]|year=1997|isbn=0814731031}} |

|||

*Freedom of speech is central to most every other right that we hold dear in the United States and serves to strengthen the democracy of our great country. It is unfortunate, then, when actions occur that might be interpreted as contrary to this honored tenet. |

|||

**{{w|Sam Farr}}, ''{{w|Congressional Record}}'', "[[s:Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press|Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press]]", (November 7, 1997). |

|||

*A law imposing criminal penalties on protected speech is a stark example of speech suppression. |

|||

**{{w|Anthony Kennedy}}, (''{{w|Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition}}'', 2002). |

|||

*First Amendment freedoms are most in danger when the government seeks to control thought or to justify its laws for that impermissible end. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought. |

|||

**{{w|Anthony Kennedy}}, (''{{w|Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition}}'', 2002). |

|||

*The Government may not suppress lawful speech as the means to suppress unlawful speech. |

|||

**{{w|Anthony Kennedy}}, (''{{w|Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition}}'', 2002). |

|||

*Dissents speak to a future age. It's not simply to say, 'My colleagues are wrong and I would do it this way.' But the greatest dissents do become court opinions and gradually over time their views become the dominant view. So that's the dissenter's hope: that they are writing not for today but for tomorrow. |

|||

**{{w|Ruth Bader Ginsburg}}, {{w|Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States}}, Interview with [[w:Nina Totenberg|Nina Totenberg]] of ''[[w:National Public Radio|National Public Radio]]'' (May 2, 2002). |

|||

[[File:Mike Godwin at Wikimedia 2010.jpg|thumb|{{w|Mike Godwin}}]] |

|||

*... while there's no 'fair use' exception when it comes to trade secrets, anyone who discovers a trade secret without violating a confidentiality agreement can disseminate it freely. For example, if you board a commuter train in Atlanta and discover that a Coca-Cola employee has left the secret formula for the company's flagship product on one of the seats, you have no obligation not to reveal it to the world. More important, this means that newspapers often may legally publish material that may have been obtained illegally, as long as they did not induce the illegal taking or know about it beforehand and as long as no one was induced or solicited by the newspaper to steal the material in question. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Mike Godwin]]|title=[[w:Cyber Rights|Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age]]|year=2003|page=217|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]|isbn=0812928342}} |

|||

*Although the freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment may benefit society generally, or communities in particular, we don't condition those freedoms on whether how we use them benefits anyone. There is no legal or constitutional requirement that each individual use these freedoms wisely. That is part of what it means to live in an open society: you get to make your own choice about whether to acquire wisdom. We don't let government choose for us. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Mike Godwin]]|title=[[w:Cyber Rights|Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age]]|year=2003|page=16|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]|isbn=0812928342}} |

|||

*Among the principles in place that have seemed to work for us are individual freedom of expression (especially for those whose expression offends us) and a strong individual guarantee of privacy in our First Amendment-protected communications. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Mike Godwin]]|title=[[w:Cyber Rights|Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age]]|year=2003|page=16|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]|isbn=0812928342}} |

|||

*In short, individual freedom of speech leads to a stronger society. But knowing that principle is not enough. You have to know how to put it to use on the Net. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Mike Godwin]]|title=[[w:Cyber Rights|Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age]]|year=2003|page=17|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]|isbn=0812928342}} |

|||

*Exploring and understanding the Net is an ongoing process. Cyberspace never sits still; it evolves as fast as society itself. Only if we fight to preserve our freedom of speech on the Net will we ensure our ability to keep up with both the Net and society. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=[[Mike Godwin]]|title=[[w:Cyber Rights|Cyber Rights: Defending Free Speech in the Digital Age]]|year=2003|page=19|publisher=[[w:Massachusetts Institute of Technology|Massachusetts Institute of Technology]]|isbn=0812928342}} |

|||

*Proponents of using government authority to censor certain undesirable images and comments on the airwaves resort to the claim that the airways belong to all the people, and therefore it's the government's responsibility to protect them. The mistake of never having privatized the radio and TV airwaves does not justify ignoring the first amendment mandate that "Congress shall make no law abridging freedom of speech." When everyone owns something, in reality nobody owns it. Control then occurs merely by the whims of the politicians in power. From the very start, licensing of radio and TV frequencies invited government censorship that is no less threatening than that found in totalitarian societies. |

|||

**{{w|Ron Paul}}, ''{{w|Congressional Record}}'', "[[s:An Indecent Attack on the First Amendment|An Indecent Attack on the First Amendment]]", (March 10, 2004). |

|||

*Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge. That's what we're doing. |

|||

**[[Jimmy Wales]], cited in — {{cite news | last =Slashdot readers' questions | first = | coauthors = Posted by Roblimo | title = Wikipedia Founder Jimmy Wales Responds | work =[[w:Slashdot|Slashdot]] | pages = | language = | publisher = | date =July 28, 2004 | url =http://interviews.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=04/07/28/1351230 | accessdate = 2008-01-04 }} |

|||

[[File:Gilbert Merritt Circuit Judge.jpg|thumb|{{w|Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}]] |

|||

*I am sure that as soon as speech was invented, efforts to suppress and control it began, and that process of suppression continues unabated. |

|||

**{{w|Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}, (''Speech at the [[w:University of Oregon|University of Oregon]]'', 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, ''Speech at the University of Oregon'', Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — {{cite book|title=Freedom of the Press|editor-first=Rob|editor-last=Edelman|publisher=Greenhaven Press|year=2006|page=75|chapter=The Lesson of ''Sullivan'' Has Been Forgotten|first=Gilbert S.|last=Merritt|authorlink=w:Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}. |

|||

*Our Founding Fathers were the first to articulate the reasons for their First Amendment, the same reasons given by Learned Hand, and by Justice Brennan in ''New York Times v. Sullivan''. It is a lesson we keep forgetting and must relearn in each succeeding generation. |

|||

**{{w|Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}, (''Speech at the [[w:University of Oregon|University of Oregon]]'', 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, ''Speech at the University of Oregon'', Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — {{cite book|title=Freedom of the Press|editor-first=Rob|editor-last=Edelman|publisher=Greenhaven Press|year=2006|page=75|chapter=The Lesson of ''Sullivan'' Has Been Forgotten|first=Gilbert S.|last=Merritt|authorlink=w:Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}. |

|||

*''New York Times v. Sullivan'' was about the suppression of speech in the South [during the 1960s]. Today's version of suppression is just another verse of the same song. |

|||

**{{w|Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}, (''Speech at the [[w:University of Oregon|University of Oregon]]'', 2004). — cited in: Gilbert S. Merritt, ''Speech at the University of Oregon'', Nashville, TN: 2004. cited in — {{cite book|title=Freedom of the Press|editor-first=Rob|editor-last=Edelman|publisher=Greenhaven Press|year=2006|page=75|chapter=The Lesson of ''Sullivan'' Has Been Forgotten|first=Gilbert S.|last=Merritt|authorlink=w:Gilbert S. Merritt, Jr.}}. |

|||

*It's hard to think of important prosecutions that have not gone forward because reporters have refused to give information. On the other hand, it's hard to make the argument that freedom of the press has been terribly infringed by the legal regime that's been set up. So it may be that the Supreme Court looks at the status quo and says: "Nothing seems terribly wrong with this. People are ignoring a little bit what we said, but it seems to have results that are not too bad, from either perspective." |

|||

**{{w|Elena Kagan}}, (''Harvard Law Bulletin'', 2005). — cited in: {{cite journal|journal=Harvard Law Bulletin|first=Robb|last=London|title=Faculty Viewpoints: Can Reporters Refuse to Testify?|date=Spring 2005|publisher=[[Harvard College|The President and Fellows of Harvard College]]}}. |

|||

*[This is] the most important question relating to the reporter's privilege: Who's entitled to claim it? When the privilege started, it was meant to cover the establishment press: the ''New York Times'', the ''Washington Post'', the major television networks. But as our media have become more diverse and more diffuse, the question of who is a member of the press, and so who gets to claim the privilege, has really come to the fore. Is the blogger entitled to claim it? And if the blogger is, then why not you, and me, and everybody else in the world? And once that happens, there's a real problem for prosecutors seeking to obtain information. So the question of whether you can draw lines in this area, and if so how, is the real question of privilege. |

|||

**{{w|Elena Kagan}}, (''Harvard Law Bulletin'', 2005). — cited in: {{cite journal|journal=Harvard Law Bulletin|first=Robb|last=London|title=Faculty Viewpoints: Can Reporters Refuse to Testify?|date=Spring 2005|publisher=[[Harvard College|The President and Fellows of Harvard College]]}}. |

|||

*Historically, of course, the Supreme Court really hasn't recognized that kind of reality. It hasn't tried to make distinctions among different kinds of press entities. And there may be strong reasons not to do this. First Amendment law is already very complicated. And if you're asking the Court now to superimpose a whole new set of distinctions on what has already become an unbearable number of complex distinctions, you may end up feeling sorry. There are lots and lots of different kinds of press entities and other speakers. And if each one gets its own First Amendment doctrine, that might be a world we don't want to live in. |

|||

**{{w|Elena Kagan}}, (''Harvard Law Bulletin'', 2005). — cited in: {{cite journal|journal=Harvard Law Bulletin|first=Robb|last=London|title=Faculty Viewpoints: Can Reporters Refuse to Testify?|date=Spring 2005|publisher=[[Harvard College|The President and Fellows of Harvard College]]}}. |

|||

[[File:Samuel Peter Nelson.jpg|thumb|Samuel Peter Nelson, author of ''[[w:Beyond the First Amendment|Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism]]'']] |

|||

*Publishing on the Internet is different than importing and exporting books, magazines, and newspapers. The Internet is a new forum, and there is something unprecedented in the idea of simultaneous, low-cost publication available to readers around the world. Speakers reach listeners in many places where they never could have been heard before. Listeners have access to the speech of individuals who may have a freedom to publish that is unknown in the listener's own country. Speakers and listeners will lose these benefits if Internet speech regulation is left to the determination of the most restrictive states. We also lose these benefits if regulation is so unpredictable as to make Internet speech more risky than warranted by the potential rewards it offers. |

|||

**{{cite book|title=[[w:Beyond the First Amendment|Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism]]|author=Samuel Peter Nelson|year=2005|page=166|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|oclc=56924685}} |

|||

*In the national debate about a serious issue, it is the expression of the minority's viewpoint that most demands the protection of the First Amendment. Whatever the better policy may be, a full and frank discussion of the costs and benefits of the attempt to prohibit the use of marijuana is far wiser than suppression of speech because it is unpopular. |

|||

**{{w|John Paul Stevens}}, (''{{w|Deborah Morse et al. v. Joseph Frederick}}'', 2007). |

|||

*Active liberty is particularly at risk when law restricts speech directly related to the shaping of public opinion, for example, speech that takes place in areas related to politics and policy-making by elected officials. That special risk justifies especially strong pro-speech judicial presumptions. It also justifies careful review whenever the speech in question seeks to shape public opinion, particularly if that opinion in turn will affect the political process and the kind of society in which we live. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Stephen Breyer|authorlink=w:Stephen Breyer|title=[[w:Active Liberty|Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution]]|isbn=0-307-26313-4|oclc=59280151|publisher=[[w:Alfred A. Knopf|Alfred A. Knopf]]|page=42|year=2008}}. |

|||

*The Court said that the First Amendment forbids statutory effort to restrict information in order to help the public make wiser decisions. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Stephen Breyer|authorlink=w:Stephen Breyer|title=[[w:Active Liberty|Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution]]|isbn=0-307-26313-4|oclc=59280151|publisher=[[w:Alfred A. Knopf|Alfred A. Knopf]]|page=51|year=2008}}. |

|||

*Traditional modern liberty — the individual's freedom from government restriction — remains important. Individuals need information freely to make decisions about their own lives. And, irrespective of context, a particular rule affecting speech might, in a particular instance, require individuals to act against conscience, inhibit public debate, threaten artistic expression, censor views in ways unrelated to a program's basic objectives, or create other risks of abuse. These possibilities themselves form the raw material out of which courts will create different presumptions applicable in different speech contexts. And even in the absence of presumptions, courts will examine individual instances with the possibilities of such harms in mind. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Stephen Breyer|authorlink=w:Stephen Breyer|title=[[w:Active Liberty|Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution]]|isbn=0-307-26313-4|oclc=59280151|publisher=[[w:Alfred A. Knopf|Alfred A. Knopf]]|page=54|year=2008}}. |

|||

*Money is not speech, it is money. But the expenditure of money enables speech, and that expenditure is often necessary to communicate a message, particularly in a political context. A law that forbade the expenditure of money to communicate could effectively suppress the message. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Stephen Breyer|authorlink=w:Stephen Breyer|title=[[w:Active Liberty|Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution]]|isbn=0-307-26313-4|oclc=59280151|publisher=[[w:Alfred A. Knopf|Alfred A. Knopf]]|page=46|year=2008}}. |

|||

[[File:AlanDershowitz2.jpg|thumb|{{w|Alan Dershowitz}}]] |

|||

*All speech should be presumed to be protected by the Constitution, and a heavy burden should be placed on those who would censor to demonstrate with relative certainty that the speech at issue, if not censored, would lead to irremediable and immediate serious harm. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Alan Dershowitz|authorlink=w:Alan Dershowitz|title=Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism|year=2008|publisher=[[w:John Wiley & Sons|John Wiley & Sons]]|isbn=0470450436|page=30}} |

|||

*I care deeply about freedom of speech, but I am also a realist about terrorism and the threat it poses. I worry that among the first victims of another mass terrorist attack will be civil liberties, including freedom of speech. The right of every citizen to express dissident and controversial views remains a powerful force in my life. I not only believe in it, I practice it. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Alan Dershowitz|authorlink=w:Alan Dershowitz|title=Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism|year=2008|publisher=[[w:John Wiley & Sons|John Wiley & Sons]]|isbn=0470450436|page=37}} |

|||

*Censorship laws are blunt instruments, not sharp scalpels. Once enacted, they are easily misapplied to merely unpopular or only marginally dangerous speech. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Alan Dershowitz|authorlink=w:Alan Dershowitz|title=Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism|year=2008|publisher=[[w:John Wiley & Sons|John Wiley & Sons]]|isbn=0470450436|page=191}} |

|||

*Under our First Amendment, a censorship law would have to be written in broad general language and could not be directed at specific religious, ethnic, racial, or political groups. Any such law could be misused by politicians to censor their political enemies or other "undesirable" groups. |

|||

**{{cite book|author=Alan Dershowitz|authorlink=w:Alan Dershowitz|title=Finding, Framing, and Hanging Jefferson: A Lost Letter, a Remarkable Discovery, and Freedom of Speech in an Age of Terrorism|year=2008|publisher=[[w:John Wiley & Sons|John Wiley & Sons]]|isbn=0470450436|page=191}} |

|||

*As a conservative who believes in limited government, I believe the only check on government power in real time is a free and independent press. A free press ensures the flow of information to the public, and let me say, during a time when the role of government in our lives and in our enterprises seems to grow every day--both at home and abroad--ensuring the vitality of a free and independent press is more important than ever. |

|||

**{{w|Mike Pence}}, ''{{w|Congressional Record}}'', "[[s:World Press Freedom Day|World Press Freedom Day]]", (May 4, 2009). |

|||

*Countries that censor news and information must recognize that from an economic standpoint, there is no distinction between censoring political speech and commercial speech. If businesses in your nations are denied access to either type of information, it will inevitably impact on growth. |

|||

* It was not by accident or coincidence that the rights to freedom in speech and press were coupled in a single guaranty with the rights of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition for redress of grievances. All these, though not identical, are inseparable. They are cognate rights, and therefore are united in the First Article's assurance. |

|||

**{{w|Hillary Rodham Clinton}}, {{w|United States Department of State}} ([[s:Secretary of State Clinton on Internet Freedom|"Secretary of State Clinton on Internet Freedom"]], ''Office of the Spokesman'', January 21, 2010). |

|||

** [[Wiley B, Rutledge]], ''Thomas v. Collins'', 323 U.S. 516, 530 (1945). |

|||

* The west has fiscalised its basic power relationships through a web of contracts, loans, shareholdings, bank holdings and so on. In such an environment it is easy for speech to be "free" because a change in political will rarely leads to any change in these basic instruments. Western speech, as something that rarely has any effect on power, is, like badgers and birds, free. |

* The west has fiscalised its basic power relationships through a web of contracts, loans, shareholdings, bank holdings and so on. In such an environment it is easy for speech to be "free" because a change in political will rarely leads to any change in these basic instruments. Western speech, as something that rarely has any effect on power, is, like badgers and birds, free. |

||

** [[Julian Assange]], |

** [[Julian Assange]], cited in — {{cite news|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/blog/2010/dec/03/julian-assange-wikileaks |title=Julian Assange answers your questions|work={{w|The Guardian}}|date=December 3, 2010|accessdate=October 23, 2012}} |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 68: | Line 287: | ||

* [[Dissent]] |

* [[Dissent]] |

||

* [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution]] |

* [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution]] |

||

* [[Freedom of religion]] |

|||

* [[Freedom of the press]] |

* [[Freedom of the press]] |

||

| Line 75: | Line 293: | ||

{{wikipedia|Freedom of speech}} |

{{wikipedia|Freedom of speech}} |

||

{{wiktionary|Freedom of speech}} |

{{wiktionary|Freedom of speech}} |

||

{{wikisource|Category:Freedom of speech}} |

|||

{{wikinews|Category:Free speech}} |

|||

* [http://observer.guardian.co.uk/focus/story/0,,1702539,00.html Timeline: a history of free speech] |

|||

{{theme-stub}} |

|||

* [http://www.bannedmagazine.com Banned Magazine, the journal of censorship and secrecy.] |

|||

* [http://www.freespeech.org/ Free Speech Internet Television] |

|||

* [http://www.indexoncensorship.org Index on Censorship] |

|||

* [http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/sunday-review/free-speech-in-the-age-of-youtube.html "Free Speech in the Age of YouTube"] in ''{{w|The New York Times}}'', September 22, 2012. |

|||

[[Category:Politics]] |

[[Category:Politics]] |

||

[[Category:Journalism]] |

[[Category:Journalism]] |

||

[[Category:Freedom of speech]] |

[[Category:Freedom of speech|*]] |

||

[[da:Ytringsfrihed]] |

[[da:Ytringsfrihed]] |

||

Revision as of 22:50, 23 October 2012

Freedom of speech is the concept of being able to speak freely without censorship. It is often regarded as an integral concept in modern liberal democracies.

Sourced

- All Ministers ... who were Oppressors, or intended to be Oppressors, have been loud in their Complaints against Freedom of Speech, and the License of the Press; and always restrained, or endeavored to restrain, both.

- Cato's Letters, John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon (Letter Number 15, Of Freedom of Speech, That the Same is inseparable from Publick Liberty, February 4, 1720).

- The liberty of the press is the birthright of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country. It has been the terror of all bad ministers; for their dark and dangerous designs, of their weakness, inability, and duplicity, have thus been detected and shown to the public, generally in too strong and just colors for them to bear up against the odium of mankind. ... A wicked and corrupt administration must naturally dread this appeal to the world; and will be for keeping all the means of information from the prince, parliament, and people.

- John Wilkes, (The North Briton, No. 1. June 5, 1762).

- The liberty of the press ... consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public: to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequences of his own temerity.

- William Blackstone, (Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1765-1769).

- There is nothing so fretting and vexatious, nothing so justly TERRIBLE to tyrants, and their tools and abettors, as a FREE PRESS.

- Samuel Adams, (Boston Gazette, 1768) — cited in: Emord, Jonathan W. (1991). Freedom, Technology, and the First Amendment. Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy. p. 61.

- The liberty of the press is essential to the security of freedom in a state: it ought not, therefore, to be restrained in this commonwealth.

- John Adams, Samuel Adams, James Bowdoin (1780). Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. pp. Article XVI.Text

- Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.

- Thomas Jefferson to Edward Carrington, January 16, 1787, The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1, General Correspondence, 1651-1827 (Library of Congress).

- I confess I do not see in what cases the Congress can, with any pretence of right, make a law to supress the freedom of the press; though I am not clear, that Congress is restrained from laying any duties whatever on certain pieces printed, and perhaps Congress may require large bonds for the payment of these duties. Should the printer say, the freedom of the press was secured by teh constitution of the state in which he lived, Congress might, and perhaps, with great propriety, answer, that the federal constitution is the only compact existing between them and the people; in this compact the people have named no others, and therefore Congress, in exercising the powers assigned them, and in making laws to carry them into execution are restrained by nothing beside the federal constitution.

- Richard Henry Lee, (The Federal Farmer, 4th letter, October 15, 1787). — cited in: Emord, Jonathan W. (1991). Freedom, Technology, and the First Amendment. Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy. pp. 75-76.

- Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

- First Amendment to the United States Constitution. December 15, 1791.

- I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it.

- To Archibald Stuart, Philadelphia, December 23, 1791.

- Cited in Thomas Jefferson (2002). "1791". in Jerry Holmes. Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of His Thoughts. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. p. 128. ISBN 0742521168.

- The power of communication of thoughts and opinions is the gift of God, and the freedom of it is the source of all science, the first fruits and the ultimate happiness of society; and therefore it seems to follow, that human laws ought not to interpose, nay, cannot interpose, to prevent the communication of sentiments and opinions in voluntary assemblies of men.

- Eyre, L.C.J., Hardy's Case (1794), 24 How. St. Tr. 206; reported in James William Norton-Kyshe, The Dictionary of Legal Quotations (1904), p. 99.

- Error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.

- Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801.

- The diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason; freedom of religion; freedom of the press, and freedom of person under the protection of the habeas corpus, and trial by juries impartially selected. These principles form the bright constellation which has gone before us and guided our steps through an age of revolution and reformation. The wisdom of our sages and blood of our heroes have been devoted to their attainment. They should be the creed of our political faith, the text of civic instruction, the touchstone by which to try the services of those we trust; and should we wander from them in moments of error or of alarm, let us hasten to retrace our steps and to regain the road which alone leads to peace, liberty, and safety.

- Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801.

- May it be to the world, what I believe it will be, (to some parts sooner, to others later, but finally to all,) the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. That form which we have substituted, restores the free right to the unbounded exercise of reason and freedom of opinion. All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man.

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Roger Weightman, June 24, 1826, in The Life and Selected Writings of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Adrienne Koch and William Peden (New York: Modern Library, 1944), p. 729.

- How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech.

- Soren Kierkegaard Either/Or Part I (1843), Swenson p. 19.

- And I honor the man who is willing to sink

Half his present repute for the freedom to think,

And, when he has thought, be his cause strong or weak,

Will risk t'other half for the freedom to speak.- James Russell Lowell, A Fable for Critics (1848), Pt. V - Cooper, st. 3.

- No law shall be passed restraining the free expression of opinion, or restricting the right to speak, write or print freely on any subject whatever.

- Oregon Constitution, (1857), Article I, Section 8.

- Strange it is that men should admit the validity of the arguments for free speech but object to their being "pushed to an extreme", not seeing that unless the reasons are good for an extreme case, they are not good for any case.

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (1859) Ch. 2, Mill (1985). On Liberty. Penguin. pp. p. 108.

- If any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. ... Though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied ... Even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension [of] or feeling [for] its rational grounds.

- John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, (1859).

- I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.

- Evelyn Beatrice Hall, Ch. 7 : Helvetius: The Contradiction (1906), p. 199.

- The general rule of law is, that the noblest of human productions — knowledge, truths ascertained, conceptions and ideas — become, after voluntary communication to others, free as the air to common use.

- When men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.

- After all, if freedom of speech means anything, it means a willingness to stand and let people say things with which we disagree, and which do weary us considerably.

- Zechariah Chafee; in Chafee (1920). Freedom of Speech. Harcourt, Brace and Howe. pp. p. 366.

- It is the function of speech to free men from the bondage of irrational fears.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State was to make men free to develop their faculties; and that in its government the deliberative forces should prevail over the arbitrary. They valued liberty both as an end and as a means. They believed liberty to be the secret of happiness and courage to be the secret of liberty. They believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- Those who won our independence by revolution were not cowards. They did not fear political change. They did not exalt order at the cost of liberty. To courageous, self-reliant men, with confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning applied through the processes of popular government, no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present, unless the incidence of the evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence.

- Louis Brandeis, (Whitney v. California, 1927).

- If there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other, it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought we hate.

- The exceptional nature of its limitations places in a strong light the general conception that liberty of the press, historically considered and taken up by the Federal Constitution, has meant, principally, although not exclusively, immunity from previous restraints or censorship.

- Charles Evans Hughes, (Near v. Minnesota, 1931).

- It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press, and of speech, is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action. It was found impossible to conclude that this essential personal liberty of the citizen was left unprotected by the general guaranty of fundamental rights of person and property.

- Charles Evans Hughes, (Near v. Minnesota, 1931).

- The liberty of the press is not confined to newspapers and periodicals. It necessarily embraces pamphlets and leaflets. ... the press in its historic connotation comprehends every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion.

- The freedom of speech and of the press, which are secured by the First Amendment against abridgment by the United States, are among the fundamental personal rights and liberties which are secured to all persons by the Fourteenth Amendment against abridgment by a state. The safeguarding of these rights to the ends that men may speak as they think on matters vital to them and that falsehoods may be exposed through the processes of education and discussion is essential to free government. Those who won our independence had confidence in the power of free and fearless reasoning and communication of ideas to discover and spread political and economic truth.

- Frank Murphy (1940). Thornhill v. Alabama. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 310 U.S. 88, 95.

- Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.

- Robert H. Jackson (1943). West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 319 U.S. 624, 638.

- The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities, and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. / One's right to life, liberty, and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no elections.

- Robert H. Jackson (1943). West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Supreme Court of the United States. pp. 319 U.S. 624, 638.

- Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

- United Nations General Assembly (December 10, 1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Palais de Chaillot, Paris: United Nations. pp. Article 19.Text

- That there is a social problem presented by obscenity is attested by the expression of the legislatures of the forty-eight States, as well as the Congress. To recognize the existence of a problem, however, does not require that we sustain any and all measures adopted to meet that problem. The history of the application of laws designed to suppress the obscene demonstrates convincingly that the power of government can be invoked under them against great art or literature, scientific treatises, or works exciting social controversy. Mistakes of the past prove that there is a strong countervailing interest to be considered in the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

- If the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of speech and press is to mean anything, it must allow protests even against the moral code that the standard of the day sets for the community.

- The standard of what offends 'the common conscience of the community' conflicts ... with the command of the First Amendment. ... Certainly that standard would not be an acceptable one if religion, economics, politics or philosophy were involved. How does it become a constitutional standard when literature treating with sex is concerned? / Any test that turns on what is offensive to the community's standards is too loose, too capricious, too destructive of freedom of expression to be squared with the First Amendment. Under that test, juries can censor, suppress, and punish what they don't like, provided the matter relates to 'sexual impurity' or has a tendency to 'excite lustful thoughts.' This is community censorship in one of its worst forms...

- We are required in this case to determine for the first time the extent to which the constitutional protections for speech and press limit a State's power to award damages in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.

- [There exists a] profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.

- Authoritative interpretations of the First Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth — whether administered by judges, juries, or administrative officials — and especially one that puts the burden of proving truth on the speaker.

- I think the conviction of appellant or anyone else for exhibiting a motion picture abridges freedom of the press as safeguarded by the First Amendment, which is made obligatory on the States by the Fourteenth.

- The censor is always quick to justify his function in terms that are protective of society. But the First Amendment, written in terms that are absolute, deprives the States of any power to pass on the value, the propriety, or the morality of a particular expression.

- The dissemination of the individual's opinions on matters of public interest is for us, in the historic words of the Declaration of Independence, an 'unalienable right' that 'governments are instituted among men to secure.' History shows us that the Founders were not always convinced that unlimited discussion of public issues would be 'for the benefit of all of us' but that they firmly adhered to the proposition that the 'true liberty of the press' permitted 'every man to publish his opinion'.

- Whatever may be the justifications for other statutes regulating obscenity, we do not think they reach into the privacy of one's own home. If the First Amendmen means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men's minds.

- First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.

- In order for the State in the person of school officials to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, it must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.