Johann Gottfried Herder: Difference between revisions

Appearance

Content deleted Content added

Allixpeeke (talk | contribs) m removed Category:1800s deaths; added Category:1803 deaths using HotCat |

→External links: Removed deadline, added new link containing the biography of the old (removed) URL Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

* [http://www.johann-gottfried-herder.net/english/ihs_society.htm International Herder Society] |

* [http://www.johann-gottfried-herder.net/english/ihs_society.htm International Herder Society] |

||

* [http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/?id=19&autor=Herder,%20%20Johann%20Gottfried&autor_vorname=%20Johann%20Gottfried&autor_nachname=Herder Selected works from Project Gutenberg (in German)] |

* [http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/?id=19&autor=Herder,%20%20Johann%20Gottfried&autor_vorname=%20Johann%20Gottfried&autor_nachname=Herder Selected works from Project Gutenberg (in German)] |

||

* [ |

* [https://www.robert-matthees.de/misc/Johann-Gottfried-Herder.pdf Herder-Biography (in German)] |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Herder, Johann Gottfried}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Herder, Johann Gottfried}} |

||

Revision as of 12:19, 6 May 2017

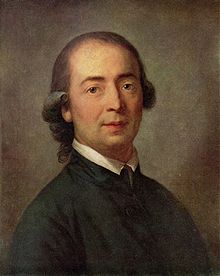

Johann Gottfried Herder (or von Herder) (August 25 1744 – December 18 1803) was a German poet, philosopher, literary critic and folksong collector. He is remembered as a theorist of the Sturm und Drang movement, and as a decisive influence on the young Goethe.

Quotes

Brave whom conquered kingdoms praise;

Bravest he who rules his passions

Who his own impatience sways.

- Wir leben immer in einer Welt, die wir uns selbst bilden.

- We live in a world we ourselves create.

- Übers Erkennen und Empfinden in der menschlichen Seele (1774); cited from Bernhard Suphan (ed.) Herders sämmtliche Werke (Berlin: Weidmann, 1877-1913) vol. 8, p. 252. Translation from Roy Pascal The German Sturm und Drang (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959) p. 136.

- Am sorgfältigsten, mein Freund, meiden Sie die Autorschaft darüber. Zu früh oder unmäßig gebraucht, macht sie den Kopf wüste und das Herz leer, wenn sie auch sonst keine üblen Folgen gäbe. Ein Mensch, der die Bibel nur lieset, um sie zu erläutern, lieset sie wahrscheinlich übel, und wer jeden Gedanken, der ihm aufstößt, durch Feder und Presse versendet, hat sie in kurzer Zeit alle versandt, und wird bald ein blosser Diener der Druckerey, ein Buchstabensetzer werden.

- With the greatest possible solicitude avoid authorship. Too early or immoderately employed, it makes the head waste and the heart empty; even were there no other worse consequences. A person, who reads only to print, to all probability reads amiss; and he, who sends away through the pen and the press every thought, the moment it occurs to him, will in a short time have sent all away, and will become a mere journeyman of the printing-office, a compositor.

- Briefe, das Studium der Theologie betressend (1780-81), Vierundzwanzigster Brief; cited from Bernhard Suphan (ed.) Herders sämmtliche Werke (Berlin: Weidmann, 1877-1913) vol. 10, p. 260. Translation from Samuel Taylor Coleridge Biographia Literaria (London: Rest Fenner, 1817) vol. 1, ch. 11, pp. 233-34.

- Der Appetit nach einer schönen Frucht ist angenehmer als die Frucht selbst.

- The craving for a delicate fruit is pleasanter than the fruit itself.

- Christoph Martin Wieland (ed.) Der deutsche Merkur vol. 20 (1781) p. 214; cited from Bernhard Suphan (ed.) Herders sämmtliche Werke (Berlin Weidmann, 1888) vol. 15, p. 307. Translation from Maturin M. Ballou Pearls of Thought (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1881) p. 13.

- Calmly take what ill betideth;

Patience wins the crown at length:

Rich repayment him abideth

Who endures in quiet strength.

Brave the tamer of the lion;

Brave whom conquered kingdoms praise;

Bravest he who rules his passions,

Who his own impatience sways.- "Die wiedergefundenen Söhne" [The Recovered Sons] (1801) as translated in The Monthly Religious Magazine Vol. 10 (1853) p. 445.

- Was in dem Herzen andrer von Uns lebt,

Ist unser wahrestes und tiefstes Selbst.- Whate'er of us lives in the hearts of others

Is our truest and profoundest self. - "Das Selbst, ein Fragment", cited from Bernhard Suphan (ed.) Herders sämmtliche Werke (Berlin: Weidmann, 1877-1913) vol. 29, p. 142. Translation from Hans Urs von Balthasar (trans. Graham Harrison) Theo-Drama: Theological Dramatic Theory (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988) vol. 1, p. 504.

- Whate'er of us lives in the hearts of others

- Sag' o Weiser, wodurch du zu solchem Wissen gelangtest?

"Dadurch, daß ich mich nie andre zu fragen geschämt."- "Tell me, O wise man, how hast thou come to know so astonishingly much?"

By never being ashamed to ask of those that knew! - "Der Weg zur Wissenschaft"; cited from Bernhard Suphan (ed.) Herders sämmtliche Werke (Berlin Weidmann, 1887-1913) vol. 26, p. 376. Translation by Thomas Carlyle, from Clyde de L. Ryals and Kenneth Fielding (eds.) The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995) vol. 23, p. 160.

- "Tell me, O wise man, how hast thou come to know so astonishingly much?"

- Jesus Christ is, in the noblest and most perfect sense, the realized ideal of humanity.

- Reported in Josiah Hotchkiss Gilbert, Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895), p. 54.

Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (1784-91)

- German quotations are cited from Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1841); English quotations from T. Churchill (trans.) Outlines of a Philosophy of the History of Man (London: J. Johnson, 1803).

- Die zwei größten Tyrannen der Erde, der Zufall und die Zeit.

- The two grand tyrants of the Earth, Time and Chance.

- Vol. 1, p. x; translation vol. 1, p. xi.

- Jeder liebt sein Land, seine Sitten, seine Sprache, sein Weib, seine Kinder, nicht weil sie die besten auf der Welt, sondern weil sie die bewährten Seinigen sind, und er in ihnen sich und seine Mühe selbst liebt.

- Every one loves his country, his manners, his language, his wife, his children; not because they are the best in the World, but because they are absolutely his own, and he loves himself and his own labours in them.

- Vol. 1, p. 13; translation vol. 1, p. 18.

- Das Maschinenwerk der Revolutionen irret mich also nicht mehr: es ist unserm Geschlecht so nötig, wie dem Strom seine Wogen, damit er nicht ein stehender Sumpf werde. Immer verjüngt in neuen Gestalten, blüht der Genius der Humanität.

- I am no longer misled, therefore, by the mechanism of revolutions: it is as necessary to our species, as the waves to the stream, that it becomes not a stagnant pool. The genius of humanity blooms in continually renovated youth.

- Vol. 1, p. 294; translation vol. 1, p. 416.

- Air, fire, water and the earth evolve out of the spiritual and material staminibus in periodic cycles of time. Diverse connections of water, air, and light precede the emergence of the seed of the simplest plant, for instance moss. Many plants had to come into being, then die away before an animal emerged. Insects, birds, water animals, and night animals preceded the present animal forms; until finally the crown of earthly organization appeared—the human being, microcosm. He is the son of all the elements and beings, Nature’s most carefully chosen conception and the blossom of creation. He must be the youngest child of Nature; many evolutions and revolutions must have preceded his formation.

- Book 1, as cited in Frank Teichmann (tr. Jon McAlice), "The Emergence of the Idea of Evolution in the Time of Goethe"

- Wie hinfällig alles Menschenwerk, ja wie drückend auch die beste Einrichtung in wenigen Geschlechtern werde. Die Pflanze blühet und blühet ab; eure Väter starben und verwesen: euer Tempel zerfällt: dein Orakelzelt, deine Gesetztafeln sind nicht mehr: das ewige Band der Menschen, die Sprache selbst veraltet; wie? und Eine Menschenverfassung, Eine politische oder Religionseinrichtung, die doch nur auf diese Stücke gebauet sein kann: sie sollte, sie wollte ewig dauern?

- How transitory all human structures are, nay how oppressive the best institutions become in the course of a few generations. The plant blossoms, and fades: your fathers have died, and mouldered into dust: your temple is fallen: your tabernacle, the tables of your law, are no more: language itself, that bond of mankind, becomes antiquated: and shall a political constitution, shall a system of government or religion, that can be erected solely on these, endure for ever?

- Vol. 2, p. 79; translation vol. 2, pp. 113-14.

- Die Natur des Menschen bleibt immer dieselbe; im zehntausendsten Jahr der Welt wird er mit Leidenschaften geboren, wie er im zweiten derselben mit Leidenschaften geboren ward, und durchläuft den Gang seiner Thorheiten zu einer späten, unvollkommenen, nutzlosen Weisheit. Wir gehen in einem Labyrinth umher, in welchem unser Leben nur eine Spanne abschneidet; daher es uns fast gleichgültig sein kann, ob der Irrweg Entwurf und Ausgang habe.

- The nature of man remains ever the same: in the ten thousandth year of the World he will be born with passions, as he was born with passions in the two thousandth, and ran through his course of follies to a late, imperfect, useless wisdom. We wander in a labyrinth, in which our lives occupy but a span; so that it is to us nearly a matter of indifference, whether there be any entrance or outlet to the intricate path.

- Vol. 2, p. 186; translation vol. 2, pp. 266-7.

- …nothing in Nature stands still; everything strives and moves forward. If we could only view the first stages of creation, how the kingdoms of nature were built one upon the other, a progression of forward-striving forces would reveal itself in all evolution.

- Book 5, as cited in Frank Teichmann (tr. Jon McAlice), "The Emergence of the Idea of Evolution in the Time of Goethe"

Quotes about Herder

- We (Goethe and Herder) had not lived together long in this manner when he confided to me that he meant to be competitor for the prize which was offered at Berlin, for the best treatise on the origin of language. His work was already nearly completed, and, as he wrote a very neat hand, he could soon communicate to me, in parts, a legible manuscript. I had never reflected on such subjects, for I was yet too deeply involved in the midst of things to have thought about their beginning and end. The question, too, seemed to me in some measure and idle one; for if God had created man as man, language was just as innate in him as walking erect; he must have just as well perceived that he could sing with his throat, and modify the tones in various ways with tongue, palate, and lips, as he must have remarked that he could walk and take hold of things. If man was of divine origin, so was also language itself: and if man, considered in the circle of nature was a natural being, language was likewise natural. These two things, like soul and body, I could never separate. Silberschlag, with a realism crude yet somewhat fantastically devised, had declared himself for the divine origin, that is, that God had played the schoolmaster to the first men. Herder’s treatise went to show that man as man could and must have attained to language by his own powers. I read the treatise with much pleasure, and it was of special aid in strengthening my mind; only I did not stand high enough either in knowledge or thought to form a solid judgment upon it. But one was received just like the other; there was scolding and blaming, whether one agreed with him conditionally or unconditionally. The fat surgeon (Lobstein) had less patience than I; he humorously declined the communication of this prize-essay, and affirmed that he was not prepared to meditate on such abstract topics. He urged us in preference to a game of ombre, which we commonly played together in the evening.

- The Autobiography of Johann Goethe, P. 349-350.

- Towards the close of the eighteenth century, Johann Gottfried Herder boldly proclaimed this idea, asserting that each age and every people embody ideals and capacities peculiar to themselves, thus allowing a fuller and more complete expression of the multiform potentialities of humankind than could otherwise occur. Herder expressly denied that one people or civilization was better than another. They were just different, in the same way that the German language was different from the French.

- William Hardy McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (1976).

- About the end of the eighteenth century fruitful suggestions and even clear presentations of this or that part of a large evolutionary doctrine came thick and fast, and from the most divergent quarters. Especially remarkable were those which came from Erasmus Darwin in England, from Maupertuis in France, from Oken in Switzerland, and from Herder, and, most brilliantly of all, from Goethe in Germany.