Allen C. Guelzo

Appearance

Allen Carl Guelzo (born 1953) is an American historian.

Quotes

[edit]2000s

[edit]- [T]he very people who write so disparagingly about it either do not understand it, or I suspect even more, understand it all too well and do not like the implications of it.

- "Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation" (23 March 2005), C-SPAN

Good Democrats and Bad Democrats (2006)

[edit]- "Good Democrats and Bad Democrats" (17 July 2006), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- What the Democratic Party has most liked to say about itself—that it is the party of the working man, the voice of the oppressed, the tribune of the people—loses some of its strut in the light of a rather long list of inconvenient facts, chiefly having to do with slavery and race. Such facts as these: that the Democrats were the party that championed chattel bondage, backed an expansionist war to expand slavery's realm, and corrupted the Supreme Court in order to open the western territories to the cancer. The party's Southern wing then led the nation into civil war in defense of slavery while its Northern wing did its best to stymie the administration of Abraham Lincoln, widely regarded by the Democrats as an accidental, even illegitimate, president. Thereafter, the party embraced Jim Crow as slavery's next-best substitute, elected a president who imposed segregation on the federal workforce, and remained the chief opponent of racial equality...

- [V]ery little has changed in the fundamental ideology of the Democratic Party since Jackson's day.

States' Rights and Wrongs (2008)

[edit]- "States' Rights and Wrongs" (18 April 2008), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- The attempt by eleven southern—and slaveholding—states to secede from the Union in the winter and spring of 1860-61 presented the United States with the greatest internal political challenge it had ever faced. Because the Constitution had created a federal Union, secession (which broke the ties of Union) was a dagger at the heart of the American polity. The fact that this secession was motivated by Southerners' determination to protect their investment in human slavery added a cruel twist of the blade. Not only did secession fracture the Union, it did so on behalf of a practice which obliterated the fundamental natural right to liberty, which the federal Constitution was supposed to protect.

- But secession struck to an even deeper level, to the very roots of popular government. The seceding states made their bolt for the door not in response to invasion or military occupation or internal taxation, but because their favored candidates did not win a presidential election. The genius of popular government was wound around the twin propositions that majorities have the privilege of winning, and that minorities have the obligation to be cooperative losers. Secession was a declaration of non-cooperation with a national vote, and since the United States in 1860 was virtually the only large-scale example of a successful popular democracy, the threat that the American republic would fracture over a lost election seemed to call into question the entire workability of popular government.

- It was not Abraham Lincoln who invented the nanny-state; it was that son of the Confederacy, Woodrow Wilson. That American conservatives, even more than American leftists, should today manage to find themselves enamored of the secessionist republic may be the crowning irony of them all.

2010s

[edit]- We live in a cynical age.

- "The Reputation of Abraham Lincoln" (12 February 2011), C-SPAN

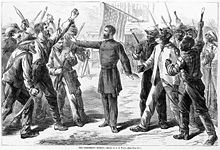

- I remember a rusher; not on a sports team. A rusher who carried an American flag, the regimental flag of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers. It is an attack on the Confederate fort known as Battery Wagner outside of Charleston, south Carolina, in July of 1863. 54th Massachusetts was an all black regiment, one of the first to be recruited after the Emancipation Proclamation. The attack was almost a suicide mission. the regiment swept up to the walls of the fort. penetrated briefly, only to be driven out with heavy losses. the rusher I am thinking of was the color sergeant of the regiment. his name was William H. Carney. He had been born a slave. He was now a free man and a soldier. He brought the stars and stripes off the ramparts of Fort Wagner, despite being wounded in the chest and leg, staggering back under fire to a field hospital, and there, just before he collapsed, he surrendered the flag into the hands of several others there saying, "The old flag never touched the ground, boys!" Before the first of January 1863 when Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law, he didn't have a flag, he doesn't have a country. He was a slave; he was an unperson. But in July of 1863, he was a free man. As a free man, there was no symbol to him of greater value than that flag. So you understand that it is difficult for me to understand why people would insult it.

- "Free Speech and the First Amendment" (20 November 2017), C-SPAN

The Bicentennial Lincolns (2010)

[edit]- "The Bicentennial Lincolns" (3 March 2010), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- [A]bsent Lincoln's proclamation, not a single fugitive slave would ever be other than a fugitive, rather than a legally free man.

- [E]ven a great man cannot be wise in everything.

Letter (2010)

[edit]- Letter (May 2010)

- Lincoln's purpose in promoting Whig capitalism was not self-interest per se, but capitalism's necessary connection to equality, self-transformation, and social mobility, which were Lincoln's real goals. The essence of a free society, Lincoln said in 1859 (and here he was pirating J.S. Mill's Principles of Political Economy), was the openness it afforded to each of its citizens to make of themselves whatever they could, without the handicap of artificial inequalities based on status, nationality, or race. One could not do this in an economic environment governed by status, racial stratification, or centralized planning. Lincoln loved the Declaration's affirmation of all men's natural equality; but that equality would be meaningless without the unfettered opportunity to use it for something. If a national bank, tariffs, and "international improvements" promoted these opportunities, then they really were serving the interests of the natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

- The answer, then, to the question of who freed the slaves is not the slaves, and not even (as Blight tries to temporize) both the slaves and Lincoln. It was Lincoln's task—and Lincoln did it. This may not work to promote anyone else's self-esteem, but it did wonders for providing freedom.

- [B]y what inattention these scurrilously racist Republicans installed the first African-American secretary of state and national security advisor, appointed a black Supreme Court justice, elected the first black U.S. senator since Reconstruction, and sent the troops into Little Rock.

Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction (2012)

[edit]

- Protecting slavery, Lincoln declared, had become the chief irritant that provoked the Southern states to reach for the solution of disunion.

- Chapter One

- It thus became vital to the peace of the planters' minds that the frustrations of the "crackers," "sandhillers," or "poor white trash" be diminished or placated at all costs. This involved, first and foremost, keeping the bogeyman of race ever before the nonslaveholders' eyes, for whatever hatreds the poor whites nursed against the planters, they nursed still greater ones against blacks.

- Chapter One

- [S]lavery was neither a backward nor a dying system in the 1850s. It was aggressive, dynamic, and mobile, and by pandering to the racial prejudices of a white republic starved for labor, it was perfectly capable of expansion.

- Chapter One

- [T]he South looked like anything but a market society, and no matter that slavery was based on the absurd and irrational prejudice of race; slavery's greatest attractions were its cheapness, its capacity for violent exploitation, and its mobility.

- Chapter One

- Slaves who ran away in Pennsylvania to join Sir William Howe's occupation of Philadelphia or who ran away in Virginia to join Lord Dumore's "Ethiopian Regiment" found themselves dumped by their erstwhile allies in Nova Scotia or sold back into slavery in the Bahamas.

- Chapter One

- The political idealism of the Revolution also encouraged, and sometimes forced, white slave owners to liberate their slaves.

- Chapter One

- [R]eligious commitment formed the backbone of much of the North's hostility to slavery.

- Chapter One

Interview with Tom Mackaman (2013)

[edit]- Interview with Tom Mackaman (March 2013)

- Lincoln is, both culturally and in terms of his economic thinking, firmly and immovably located in the center of what we can call liberal democratic thought in the 19th century. He is very much market oriented, with tremendous confidence in the power of a capitalist society to transform for the better, and he believes in opening the possibilities of that society to as many as possible. To him, that’s what’s coterminous with liberty.

- To Lincoln, slavery undercut the free labor outlook on the world because it denied advancement and self-improvement. For Lincoln, the great attraction of any economic regime was the degree to which it permitted accumulation and self-promotion. He once described the ideal system as being one where the penniless beginner starts out working for somebody else, accumulates capital on his own by dint of savings, goes into business for himself, and then eventually becomes so successful that he hires others, who in turn continue the cycle. And he spoke of that as being the order of things in a society of equals. For him, the very notion of equality is a matter of equality of openness, aspiration, and opportunity.

- [Abraham Lincoln believed that] [t]he only reason people do not succeed in a capitalist environment is because they are improvident, they are lazy, they are good for nothing, or they experience some incredible turn of bad luck—that’s why "better luck next time." That may seem like vanishingly small consolation to people who’ve just come through a depression, but for Lincoln, that kind of hardship paled beside slavery. Slavery says that there is a category of people that can never be allowed to rise, that cannot improve themselves no matter how hard they try because they will always be slaves. It’s very much the classic disjuncture between the Enlightenment and feudalism. Feudalism talks about people being born with status, and everyone comes into this world equipped with a status. This status is either free or slave, serf or nobility, elect or damned, whatever. For the Enlightenment people come into this world armed with rights, and the ideal political system is the system that allows them to realize those rights, to use those rights in the freest and most natural fashion possible.

- Lincoln habitually would tell people he was totally ignorant of a subject which in fact he was quite well versed in, because then they would underestimate him, and when they underestimated him they would fall into his trap. Leonard Swett once said that anybody who mistook Lincoln for a simple man would soon end up with his back in a ditch.

- Lincoln was not eloquent in the usual 19th century way, certainly not in the romantic way. He was not a man of frothing at the mouth or shaking his fist in a dramatic way. Lincoln was logic, and when he got the hook in your mouth he would pull you in no matter how much line was involved. One observer of the Lincoln-Douglas debates said that if you listened to Lincoln and Douglas for five minutes, you would go with Douglas. If you listened to them for an hour you always went with Lincoln.

- What we see in Lincoln is a collection of the virtues we think are most important in a democratic leadership.

- Anyone who sits down for a moment to think about what the alternative would have looked like—a successful breakaway Confederacy—and how that would have flowed downstream has to be with impressed with what Lincoln was able to save us from. There is in the end no intrinsic reason why the Southern Confederacy should not have achieved its independence. And if they had, that would have had serious implications for the later role the North American continent plays in world affairs. Imagine a North American continent as divided politically and economically as South America. This would take the United States off the table as a major world player, and then what would you do with the history of the 20th century?

- [O]ne reason there is no socialism in America is because of Lincoln. In the American context Lincoln imparted to liberal democracy a sense of nobility and purpose that it has not always had in other contexts. He makes democracy something transcendent, and especially at Gettysburg where he talks about the nation having this new birth of freedom. He ratchets the horizons of liberal democracy right up past the spires of Cologne Cathedral and he makes it this glowing attractive ideal that people are willing to make these tremendous sacrifices to protect. Because at the end of the day this is what the Civil War is about—it’s about the preservation of liberal democracy. In the 1860s the United States was the last Enlightenment experiment that was still standing. What you had in the climate of mid-19th century Europe was the renaissance of romantic aristocracy.

- Lincoln sees American democracy as a last stand, what he calls the last, best hope. And if this goes down, we may so discredit the whole notion of democracy that no one will ever want to go this way again, and so this is the test. It’s a test of whether or not we’ll have this new birth of freedom, if we’ll finally shuck off these last husks of aristocracy and move forward in the direction of democracy. That for him is the vital issue.

- People today often want to separate slavery, and say that Lincoln was interested in preserving the union and not in destroying slavery. No, that gets it exactly wrong. The two are as knotted together as a rope, because the only union worth preserving is a union that has abjured slavery. So for Lincoln to get rid of slavery is to purge America of the aristocratic poison. He once said that slavery was the one retrograde institution that was poisoning the American republic, keeping the American republic from realizing its full potential.

- [O]n the whole, given that the environment of the U.S. in the middle of the 19th century is so white supremacist in its assumptions, Lincoln is actually quite remarkable for standing apart from that.

- [A]sk the slaves themselves how they were freed, and they will say, “Lincoln’s proclamation.” The testimony of freed people before the joint committee on reconstruction—about how they became free is uniform. They were well aware that the Fugitive Slave Laws and Constitutional provisions for the rendition of slaves were still in force. The position of runaways remained perilous. The Emancipation Proclamation resolved that.

- What if George McClellan had won the presidency in 1864, defeating Lincoln? He would have immediately begun negotiations with the Confederacy. And it is difficult for me to imagine that those negotiations would have not involved some sort of provision for rendition.

Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (2013)

[edit]

- [E]mancipation cannot be so easily detached from union (which is another way of saying that racial justice and liberal democracy rise or fall with each other).

- p. xviii

- Union (and the liberal democracy it represented) and emancipation were not, after all, mutually exclusive goals. Unless the Union was restored, there would be no practical possibility of emancipation, since the overwhelming majority of American slaves would, in that case, end up living in a foreign country, and beyond the possible grasp of Lincoln's best antislavery intensinos.

- p. xviii

- [N]o democracy worth its name could continue to drag the burden of slavery around after it.

- From the moment they took a republic rather than a monarchy as the shape of their government, Americans prided themselves on being a nation of peace, dedicated to the arts of commerce rather than the rapacity of empire and "the spirit of war."

- p. 9

- Defending slavery deprived the Confederate soldier to the same claim to nobility, but not to tragedy.

- p. 14

- [M]any quite frankly fought to protect slavery, which laid on the survivors of the rebel armies an incubus to which few were willing to admit in alter years. More than just one out of three Confederates whose campfires dotted South Mountain in the June dusk owned slaves... [T]hey brought slaves with them on campaign to tend to the menial jobs... The slave system had invested them with an instinctive impulse for domestic dictatorship; they could brawl, stab, and shoot, in and out of race tracks and saloons, and still assume that they were God's natural aristocrats.

- p. 15

Interview with Andre Damon (2013)

[edit]- Interview with Andre Damon (1 July 2013)

- In 1863, the United States is really the only free-standing democracy in the world. That all across the stage of world history the forces of reaction have been on the march, ever since Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Everywhere that there is aristocracy in the world, there is sympathy for the Confederacy, and rejoicing that this civil war looks like it's finally going to paid for good to these notions of democracy.

The Logic of Liberty (2014)

[edit]- "The Logic of Liberty" (31 October 2014), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- Emancipation, not colonization, was the real goal to which the logic of the American Founding was driving the nation.

- [E]verything in the reasoning of the founders pointed inexorably toward the incompatibility of liberty and equality with slavery...

- To draw a bright line from the founders to the Civil War has become one of the most difficult interpretative tasks confronting American historians, if only because we confront, on the one hand, truculent bands of neo-Confederates who struggle to disguise the fatal corruption of the Confederate rebellion in modern libertarian garb, and, on the other, the brigades of neo-Progressives who have been only too happy to sunder the founders from emancipation in order to subvert any notion that an 18th-century Constitution still has viability after being crisped up in the flames of the Civil War. What both neo- camps ignore is how hugely the accomplishment of the founders—whether in the secular language of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton or the sacred language of the Awakeners—represented a decisive break with all previous notions of human political organization. The achievement of Lincoln was to carry that break relentlessly forward against its oldest foe. The achievement of our times—if there will be one to write about—will depend largely on how we resist the newer, more subtle, forms of dehumanization which now, like the tireless tide, creep all around us again.

Lecture (2017)

[edit]- Lecture (16 February 2017)

- Abraham Lincoln was a repo man.

Defending Reconstruction (2017)

[edit]- "Defending Reconstruction" (1 May 2017), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- There are no Reconstruction reenactors. And who would want to be? Reconstruction is the disappointing epilogue to the American Civil War, a sort of Grimm fairy tale stepchild of the war and the ugly duckling of American history. Even Abraham Lincoln was uneasy at using the word "reconstruction"--he qualified it with add-ons like "what is called reconstruction" or "a plan of reconstruction (as the phrase goes)"--and preferred to speak of the "re-inauguration of the national authority" or the need to "reinaugurate loyal state governments." Unlike the drama of the war years, Reconstruction has no official starting or ending date. Although we usually bookend the period with the Confederate surrender in 1865 and the withdrawal of federal occupation troops in 1877, people had been talking about "reconstruction" even before the shooting began in 1861, and the federal occupation troops who were withdrawn in 1877 were by that time little more than a corporal's guard. In some sense, Reconstruction ended when Democrats managed to regain control of the House of Representatives in 1874; other parts of it spluttered on...

- Reconstruction aspired to restore the foundations of freedom to a wayward South and it expected to triumph as effortlessly as 19th-century liberal notions of progress had promised. Instead, the same Romantic feudalism that had created the old Southern order reasserted its hegemony, and postwar Southern aristocrats appealed to a set of cultural and racial biases which safely defused the importance of property, and sharply restricted access to it. This might have been averted had the victorious Union been willing to pour the resources into Reconstruction it had devoted to winning the war. But Reconstruction became a symbol of how quickly political fatigue afflicts liberal democracies. Moreover, understanding Reconstruction as a bourgeois revolution which was strangled in its cradle by vengeful cotton nabobs offers some larger parallels to the optimistic era that prevailed between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of Islamic state terrorism.

- Francis Fukuyama seized on the ignominious collapse of the Soviet system as proof that “the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution” was “the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” and Marxism’s “death as a living ideology of world historical significance.” That conclusion was, to say the least, premature, not only because it reckoned without the rise of an Islamist theocracy or the fallout from the 2008 worldwide recession, which provoked a renascence of Marxist advocacy in the writings of Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, Alain Badiou, the Occupy Movement, and Thomas Picketty. This pattern is, again, an echo of what happened in Reconstruction, and it warns those who yet believe that liberal democracy is the most desirable political future to be wary of Whiggish assumptions about democracy’s inevitability. Human society has oscillated between desires for stability, security, and reciprocity—which is what feudalism, Marxism, and theocracy promise—and desires for mobility, liberty, and profit—which is what the Enlightenment offered on a world-historical scale. There is nothing that can be declared permanent in a bourgeois revolution, and our own Reconstruction, not to mention a good deal of recent history, is the unhappy proof.

Interview with Sara Gabbard (2018)

[edit]- Interview with Sara Gabbard (2018)

- Just think: there are no Reconstruction reenactors, no reconstructed Reconstruction villages on the order of Colonial Williamsburg or Old Sturbridge, no Reconstruction observances and ceremonies.

- At the end of the Civil War, the "Slave Power" had been destroyed, free-labor Republicanism was triumphant, and the freed slave was poised on the verge of assuming an equal place in American society with every other citizen. Fifteen years later, the one-time slaveholders were back in control of the South, free-labor Republicanism was coping with the first stresses of mass industrialization in its own Northern backyard, and the freedmen were consigned to an economic peonage that offered little practical improvement on enslavement. It began to seem that a great opportunity had been bobbled away.

- [T]he Civil War’s victors ended up blaming themselves, or at least allowing the defeated South to foist the blame on them. Postwar Southerners never accepted the results of military defeat in the war, and they resisted Reconstruction (and much more effectively than they had resisted the Union armies)...

- Technically, Reconstruction was "over" when the last of the Confederate states had written new state constitutions and elected representatives and senators in conformity with the Reconstruction Acts. This happened fairly quickly, between June 1868 and July 1870, and it put in place state governments that were largely dominated by Republicans and that made heroic efforts to make a reality of voting rights for the freed slaves. But one by one, the wheels came off these reconstructed state governments and the old Southern Democratic power machines regained control. But “regained” is too anodyne; “overthrew” is the real word, since the recapture of these state governments was accomplished by violence and black voter intimidation.

- [I]n a liberal democracy, sovereignty lies in the people at large; and our governing structures exist to implement that will.

- [T]he attention span for political affairs in a democracy is a limited one. The fundamental genius of a liberal democracy lies in how it restrains government and permits its citizens to pursue their own interests without unnecessary molestation. So when we must address political or national issues—whether it’s “On to Richmond” or “54-40 or Fight”—we want problems addressed swiftly, so that we can turn back to our private concerns. When that doesn’t happen, we turn back to the private concerns anyway, and the problems and their solutions are left to fester or find their own solutions.

- Southerners carried out an asymmetrical kind of political warfare that the rest of the country eventually ran out of patience in confronting. We had the West to win, the Pacific Rim to open, a new economy to create, a catastrophic financial panic to overcome, and in the end, dealing with the political insurgencies of disaffected ex-Confederates simply couldn’t compete.

- In 1968, we won a substantial military victory, as we did in 2003; we then fumbled them away because of our inability to keep a long-term focus on the political aftermath, and we live with the results to this day. This is, so to speak, the advantage tyrants and dictators have over democracies: they can force their people to pay attention to the problems they choose to address, and for as long as they wish (or until their people overthrow them, which is not all that common).

- Reconstruction was overthrown, not that it ground to an exhausted halt. Indifference and inattention helped to divert resources from Reconstruction, but the real dagger was planted in Reconstruction’s back by political insurgency.

- [F]or all the economic destruction levied on the South by the war, the people who ran the economic show before the war were still running it afterwards. Former slaveholders were thus free to use cotton profits to maintain a version of the plantation system and force the freedpeople into peonage; peonage, in turn, gave white Democrats the power to control black voting...

- Even though Lincoln won a resounding victory at the polls in his re-election campaign in November 1864, the Democratic opposition did not, by any means, disappear, and much of it remained militantly hostile to black enfranchisement and black equality, North as well as South.

- I know it seems strange to say that Progressivism wore a white supremacist face. But the most thorough going Progressive president, Woodrow Wilson, was an unabashed white supremacist. So, it should not be surprising...

- [N]either the Civil War nor Reconstruction fit neatly into traditional Marxist frameworks. Both the Civil War and Reconstruction belong to a chapter in American history in which the United States was still an overwhelmingly agricultural economy, and the contest that was waged between 1861 and 1865 was largely an argument (in economic terms) between the free-labor family farm and the slave-labor cotton plantation.

- [W]e need to shove aside the notions of the Progressives and Lost-Causers, that Reconstruction was some sort of Vichy occupation of a poor, pitiable South, as well as of the Marxists, that Reconstruction could have been the beginning of a socialist America had not the monied interests suppressed it. Neither of these approaches has much sense of the texture of Reconstruction’s reality.

- [W]hat Reconstruction succeeded in doing: it helped us avoid a renewed outbreak of civil war (which, considering the history of civil conflicts, is no small achievement); it laid the legal and constitutional foundations for a more egalitarian America, foundations that it took only sixty-five years to revitalize into the Civil Rights Movement; it restored the original balance of constitutional federalism, putting aside the states’ rights absolutism of the pre-war Southern aristocracy. But I do not say this to encourage any historical Pollyannaism about Reconstruction. That restored federal balance permitted the emergence of the first women’s voting rights legislation, the curtailing of municipal corruption, and the introduction of widespread public schooling; it also permitted the emergence of Jim Crow. But as Lincoln said, “this is a world of compensation.” The historical good and the evil, even in Reconstruction, do not come unmixed.

- Reconstruction should be considered as a "bourgeois revolution."

Bullwhip Feudalism (2018)

[edit]- "Bullwhip Feudalism" (30 July 2018), Claremont Review of Books, California: Claremont Institute

- [T]he real issue of the Civil War was a terrible ideological derangement that had lifted an entire portion of the American Republic away from the ideological moorings of the founders...

- [O]ligarchy, strictly speaking, is a regime "in which a rich minority rules for the advantage of the rich minority and in which the people composing that political society are ranked...because the ruling principle of that regime is the principle of natural inequality." Aristotle called it a deviant form of aristocracy (in the same way that tyranny is a deviant form of monarchy), and in practical terms, it exhibits its form through excessive concentrations of property in the hands of a few, the reservation of education to the elite, and the organization of government to serve the purposes of the oligarchs.

- Southern slave owners constantly agitated in the 1850s for state centralization of economic activities that would promote slave agriculture: state-sponsored agricultural surveys, state-subsidized agricultural periodicals, and state investment in railroads (at more than twice the rate of Northern state assistance) which would unite the South and the West and encourage more intensive cotton cultivation. They were, as historian John Majewski remarks, the forerunners of the "southern Progressives of the early twentieth century."

- Where a republic demands equality, and equality tends to ensure mobility, oligarchy is about hierarchy and stasis.

- Trying to plant such an oligarchy in the midst of what was otherwise the world's most successful republican regime was no small task, and it required the invention of ideological monstrosities to justify it. In the Southern case, the monstrosities included race-based rationales for the enslavement of Africans.

- The cotton nabobs had made the South a no-go area for the Constitution...

- [T]he defeat of the Confederacy did not necessarily mean the end of oligarchy. Despite the destructiveness of the war, Southern land tenures remained largely undisturbed, and in the Reconstruction years, the sadder-but-wiser oligarchs learned how, once again, to play on the racial hatreds they had spent decades so sedulously cultivating among the white yeomanry.

- [T]he Calhounite Confederacy, despite its Lost Cause apologists and their determination to apotheosize the Confederacy as "conservative", has nothing that binds it to a genuinely republican conservatism. The Confederacy was what William Russell Howard called "a modern Sparta", not a democratic Athens, much less a republican Rome.

Free Speech and Its Present Crisis (2018)

[edit]- "Free Speech and Its Present Crisis: In today’s America, the right to express one’s opinion is threatened by activists and authorities alike." (October 2018), City Journal

- Today’s despisers of free speech have their roots in a different ideology from the tribal sort that was used to justify slaveholding and Puritanism. This newer ideology began with Karl Marx—or rather, with the struggle of Marxist intellectuals to explain the failure of the European proletariat to rise in violent revolution at the outbreak of World War I. Rather than joining in solidarity with the working classes of other nations, European workers rallied in dismaying numbers to their national flags, exhausted themselves in a four-year killing spree that beggared all previous descriptions of war, and then succumbed to waves of populist fascism. The only revolution that Marxists could tease out of the charnel house of the Great War was a coup d’état in the most backward and least industrially developed empire of Europe and, even then, only by the substitution of what Vladimir Lenin called a “vanguard” of Marxist elites rather than a spontaneous uprising of the workers.

- [T]he genuinely oppressed—as opposed to the hustlers of faux outrage—have always known freedom of speech to be their best friend.

- [D]o not expect Americans to believe that freedom of speech is some disguised puppetry of the powerful. It is, to the contrary, an indispensable ingredient in the recipe for preventing tyrannies, be they of the left or right, be they in the name of the Fatherland, the Volk, or the workers. To say otherwise is merely to perform what Michael Polanyi called a “moral inversion”—an intellectual juggling act in which we are asked, in Orwellian terms, to regard freedom as slavery, discrimination as nondiscrimination, and truth as power.

- There has never been a freedom, of course, that someone has not proved ingenious enough to abuse.

- Culture made the use of the F-bomb on television unthinkable in 1965; 40 years later, HBO would be lost without it.

- The real crime of white supremacy was not that it put up statues, or even that it made speeches, but that it attacked citizens and passed laws.

- [T]he wall of separation between public and private higher education has been eroding for the last half-century. Funding from public sources now constitutes the bulk of higher-education resources in the United States, whether in the form of government subventions for research and programs, or in the much vaster influx of government-guaranteed student loans. For all realistic purposes, the distinction between public and private higher education has ceased to exist. Further, the vast numbers of young American adults being drawn in to the college and university system (some 20.4 million, up by 25 percent from 2000 alone)—on the assumption that college degrees are virtually a sine qua non of entrance into profitable commerce or lucrative professions—has evaporated what little is left of the pretense that academe constitutes some monastic realm, beyond the orbit of civil society.

- Reverence for free speech is deeply embedded in American life, but speech cannot be protected unless those who acknowledge its value set aside their partisan differences for a moment and trust one another enough to say that the outrages against free speech must end.

- We are not talking here about mere bad frat-boy behavior or professorial eccentricity but about orchestrated campaigns to assault the fundamental liberties of the American republic, tolerated by campus administrators who, in equal measure, fear confrontations with student activists as a threat to their career advancement, and hope that no news of their cravenness leaks out to the press and the alumni.

- The anti-free-speech fanatics on campuses and throughout the country have raised their hand against the idea that guarantees us life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

2020s

[edit]- [A]s Americans, our identity does not rest on race, religion, blood, or soil, but on a historical proposition, that all men are created equal. Take that away, render it vain, illusory, or nugatory, and we lose all identity as Americans. And then what remains for us? The great Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said that the first step a tyrant takes toward enslaving a people is to steal their history, for in that case, no one has anything from the past with which to compare the present, and any horror can be normalized.

- "1619 and the Narrative of Despair" (11 May 2020), National Review

- It was once said, as a commercial joke, that it’s not nice to fool Mother Nature. The same is true in this case, but not as a joke: It’s not nice to fool with history.

- "1619 and the Narrative of Despair" (11 May 2020), National Review

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Allen C. Guelzo on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Allen C. Guelzo on Wikipedia