Daniel Defoe

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

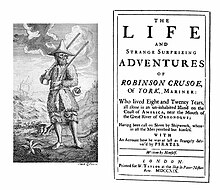

Daniel Defoe (13 September 1660 - 24 April 1731), was an English writer, journalist and spy, who gained enduring fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe.

Quotes

[edit]

The good die early, and the bad die late.

The Devil always builds a chapel there;

And 'twill be found, upon examination,

The latter has the largest congregation.

- W. Guerney Benham, A Book of Quotations, Proverbs and Household Words (1914), pp. 106–107

- We loved the doctrine for the teacher's sake.

- The Character of the Late Dr. S. Annesly (1697).

- Alas the Church of England! What with Popery on one hand, and schismatics on the other, how has she been crucified between two thieves!

- Hail, hieroglyphic State machine,

Contrived to punish fancy in;

Men that are men in thee can feel no pain,

And all thy insignificance disdain!- Hymn to the Pillory (1703).

- Next, bring some lawyers to thy bar,

By innuendo they might all stand there;

There let them expiate that guilt,

And pay for all that blood their tongues have spilt.

These are the mountebanks of state,

Who by the sleight of tongues can crimes create,

And dress up trifles in the robes of fate,

The mastiffs of a Government,

To worry and run down the innocent.- Hymn to the Pillory (1703).

- Reason, it is true, is DICTATOR in the Society of Mankind; from her there ought to lie no Appeal; But here we want a Pope in our Philosophy, to be the infallible Judge of what is or is not Reason.

- An Essay upon Publick Credit (1710).

- All men would be tyrants if they could.

- Jure divino: a satyre, Introduction, l. 2 (1706).

- The best of men cannot suspend their fate:

The good die early, and the bad die late.- Character of the Late Dr. S. Annesley (1715).

- 'Tis very strange Men should be so fond of being thought wickeder than they are.

- A System of Magick (1726).

- It is better to have a lion at the head of an army of sheep than a sheep at the head of an army of lions.

- Wise men affirm it is the English way

Never to grumble till they come to pay.- Britannia, l. 84.

- The best of men cannot suspend their fate;

The good die early, and the bad die late.- Character of the late Dr. S. Annesley.

- We loved the doctrine for the teacher's sake.

- Character of the late Dr. S. Annesley.

- Nature has left this tincture in the blood,

That all men would be tyrants if they could.- The Kentish Petition (1701), Addenda. l. 11.

- In trouble to be troubled

Is to have your trouble doubled.- The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719)

- A true-bred merchant is the best gentleman in the nation.

- The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719)

The History of Projects (1697)

[edit]- The art of war, which I take to be the highest perfection of human knowledge.

- Introduction.

- Self-destruction is the effect of cowardice in the highest extreme.

- Of Projectors.

- Women, in my observation, have little or no difference in them, but as they are or are not distinguished by education.

- Of Academies.

The True-Born Englishman (1701)

[edit]- Henry Morley, ed., The Earlier Life and the Chief Earlier Works of Daniel Defoe (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1889), pp. 175-218

- The grand contention's plainly to be seen,

To get some men put out, and some put in.- Introduction.

- Wherever God erects a house of prayer,

The Devil always builds a chapel there;

And 'twill be found, upon examination,

The latter has the largest congregation.- Pt. I, l. 1. Compare: "Where God hath a temple, the Devil will have a chapel", Robert Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy, part iii, section 4, Memb. 1, Subsect. 1.

- From this amphibious ill-born mob began

That vain, ill-natured thing, an Englishman.- Pt. I, ll. 132–133

- The royal refugee our breed restores

With foreign courtiers and with foreign whores,

And carefully repeopled us again,

Throughout his lazy, long, lascivious reign.- Pt. I, l. 233-236

- Referring to Charles II

- That heterogeneous thing, an Englishman.

- Pt. I, l. 280.

- Wealth, howsoever got, in England makes

Lords of mechanics, gentlemen of rakes;

Antiquity and birth are needless here;

'Tis impudence and money makes a peer.- Pt. I, l. 360-363.

- Great families of yesterday we show,

And lords whose parents were the Lord knows who.- Pt. I, l. 374.

- In their religion they are so uneven,

That each man goes his own byway to heaven.- Pt. II, l. 104.

- No panegyric needs their praise record;

An Englishman ne'er wants his own good word.- Pt. II, l. 152.

- Restraint from ill is freedom to the wise;

But Englishmen do all restraint despise.- Pt. II, l. 206.

- For Englishmen are ne'er contented long.

- Pt. II, l. 244.

- And of all plagues with which mankind are cursed,

Ecclesiastic tyranny's the worst.- Pt. II, l. 299.

- When kings the sword of justice first lay down,

They are no kings, though they possess the crown.

Titles are shadows, crowns are empty things,

The good of subjects is the end of kings.- Pt. II, l. 313.

- For justice is the end of government.

- Pt. II, l. 368.

- But English gratitude is always such

To hate the hand which doth oblige too much.- Pt. II, l. 409.

Robinson Crusoe (1719)

[edit]- He told me I might judge of the happiness of this state by this one thing - viz. that this was the state of life which all other people envied; that kings have frequently lamented the miserable consequence of being born to great things, and wished they had been placed in the middle of the two extremes, between the mean and the great; that the wise man gave his testimony to this, as the standard of felicity, when he prayed to have neither poverty nor riches. He bade me observe it, and I should always find that the calamities of life were shared among the upper and lower part of mankind; but that the middle station had the fewest disasters.

- Ch. 1, Start in Life.

- I have since often observed, how incongruous and irrational the common temper of mankind is, especially of youth, to that reason which ought to guide them in such cases - viz. they are not ashamed to sin, and yet are ashamed to repent. Not ashamed of the action for which they ought justly to be esteemed fools, but are ashamed of the returning, which can only make them be esteemed wise men.

- Ch. 1, Start in Life.

- All evils are to be considered with the good that is in them, and with what worse attends them.

- Ch. 5, First Weeks on the Island.

- And I add this part here, to hint to whoever shall read it, that whenever they come to a true sense of things, they will find deliverance from sin a much greater blessing than deliverance from affliction.

- Ch. 6, Ill and Conscience-stricken.

- Now I saw, though too late, the folly of beginning a work before we count the cost, and before we judge rightly of our own strength to go through with it.

- Ch. 9, A Boat.

- In a word, the nature and experience of things dictated to me, upon just reflection, that all the good things of this world are no farther good to us than they are for our use; and that, whatever we may heap up to give others, we enjoy just as much as we can use, and no more.

- Ch. 9, A Boat.

- I learned to look more upon the bright side of my condition, and less upon the dark side, and to consider what I enjoyed rather than what I wanted; and this gave me sometimes such secret comforts, that I cannot express them; and which I take notice of here, to put those discontented people in mind of it, who cannot enjoy comfortably what God has given them, because they see and covet something that He has not given them. All our discontents about what we want appeared to me to spring from the want of thankfulness for what we have.

- Ch. 9, A Boat.

- We never see the true state of our condition till it is illustrated to us by its contraries, nor know how to value what we enjoy, but by the want of it.

- Ch. 10, Tames Goats.

- It happened one day, about noon, going towards my boat, I was exceedingly surprised with the print of a man's naked foot on the shore, which was very plain to be seen on the sand.

- Ch. 11, Finds Print of Man's Foot on the Sand.

- To-day we love what to-morrow we hate; to-day we seek what to-morrow we shun; to-day we desire what to-morrow we fear, nay, even tremble at the apprehensions of.

- Ch. 11, Finds Print of Man's Foot on the Sand.

- Fear of danger is ten thousand times more terrifying than danger itself.

- Ch. 11, Finds Print of Man's Foot on the Sand.

- It is never too late to be wise.

- Ch. 12, A Cave Retreat.

- How frequently, in the course of our lives, the evil which in itself we seek most to shun, and which, when we are fallen into, is the most dreadful to us, is oftentimes the very means or door of our deliverance, by which alone we can be raised again from the affliction we are fallen into.

- Ch. 13, Wreck of a Spanish Ship.

- What is one man's safety is another man's destruction.

- Ch. 13, Wreck of a Spanish Ship.

- There are some secret springs in the affections which, when they are set a-going by some object in view, or, though not in view, yet rendered present to the mind by the power of imagination, that motion carries out the soul, by its impetuosity, to such violent, eager embracings of the object, that the absence of it is insupportable.

- Ch. 13, Wreck of a Spanish Ship.

- My man Friday.

- First appears in Ch. 14, A Dream Realized.

The Education of Women (1719)

[edit]

- I have often thought of it as one of the most barbarous customs in the world, considering us as a civilized and a Christian country, that we deny the advantages of learning to women. We reproach the sex every day with folly and impertinence; while I am confident, had they the advantages of education equal to us, they would be guilty of less than ourselves.

- The soul is placed in the body like a rough diamond; and must be polished, or the lustre of it will never appear. And ’tis manifest, that as the rational soul distinguishes us from brutes; so education carries on the distinction, and makes some less brutish than others.

- A woman well bred and well taught, furnished with the additional accomplishments of knowledge and behaviour, is a creature without comparison. Her society is the emblem of sublimer enjoyments, her person is angelic, and her conversation heavenly. She is all softness and sweetness, peace, love, wit, and delight. She is every way suitable to the sublimest wish, and the man that has such a one to his portion, has nothing to do but to rejoice in her, and be thankful.

- For I cannot think that God Almighty ever made them so delicate, so glorious creatures; and furnished them with such charms, so agreeable and so delightful to mankind; with souls capable of the same accomplishments with men: and all, to be only Stewards of our Houses, Cooks, and Slaves.

Quotes about Daniel Defoe

[edit]- Robinson Crusoe did not deal with love. Defoe's other stories, which are happily forgotten, are bad in their very essence. Roxana is an accurate example of what a bad book may be. It relates the adventures of a woman thoroughly depraved, and yet for the most part successful, -- is intended to attract by licentiousness, and puts off till the end the stale scrap of morality which is brought in as a salve to the conscience of the writer. Putting aside Robinson Crusoe, which has been truly described as an accident, Defoe's teaching as a novelist has been altogether bad.

- Anthony Trollope, "Novel-Reading" The Nineteenth Century, January 1879, in David Dowling, Novelists on Novelists (1983)