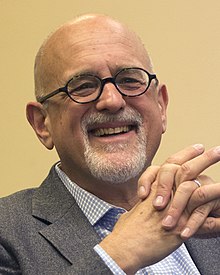

Daniel T. Gilbert

Appearance

Daniel Todd Gilbert (born November 5, 1957) is an American social psychologist, Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, and writer. He is known for his research (with Timothy Wilson of the University of Virginia) on affective forecasting.

Quotes

[edit]- "Dangerous" does not mean exciting or bold; it means likely to cause great harm. The most dangerous idea is the only dangerous idea: The idea that ideas can be dangerous.

- Daniel T. Gilbert (2007) in: John Brockman. What is your dangerous idea?: today's leading thinkers on the unthinkable. Harper Perennial, 2007, p. 42

- The benefit of knowledge is that it makes the world more predictable, but the cost is that a predictable world sometimes seems less delicious, less exciting, less poignant.

- Daniel Gilbert, Timothy Wilson, David Centerbar, & Deborah Kermer, The Pleasures of Uncertainty: Prolonging Positive Moods in Ways People Do Not Anticipate, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1): 5 (2005).

- We live in a world in which people are censured, demoted, imprisoned, beheaded, simply because they have opened their mouths, flapped their lips, and vibrated some air. Yes, those vibrations can make us feel sad or stupid or alienated. Tough shit. That's the price of admission to the marketplace of ideas. Hateful, blasphemous, prejudiced, vulgar, rude, or ignorant remarks are the music of a free society, and the relentless patter of idiots is how we know we're in one. When all the words in our public conversation are fair, good, and true, it's time to make a run for the fence.

- Daniel T. Gilbert (2007) in: John Brockman. What is your dangerous idea?: today's leading thinkers on the unthinkable. Harper Perennial, 2007, p. 43

"Ordinary personology." 1998

[edit]Daniel T. Gilbert, "Ordinary personology." The handbook of social psychology 2 (1998): 89-150

- Heider began by assuming that just as objects have enduring qualities that determine their appearances, so people have stable psychological characteristics that determine their behavior.

- p. 94; As cited in Bertram F. Malle, "Attribution theories: How people make sense of behavior." Theories in social psychology (2011): 72-95; p. 74

- If a pitcher who wishes to retire a batter (motivation) throws a burning fastball (action) directly into the wind (environmental influence), then the observer should conclude that the pitcher has a particularly strong arm (ability). If a batter tries to hit that ball (motivation) but fails (action), then the observer should conclude that the batter lacked coordination (ability) or was blinded by the sun (environmental influence).

- p. 96; as cited in Malle (2011, 75)

Stumbling on Happiness, 2006

[edit]

- Among life’s cruelest truths is this one: Wonderful things are especially wonderful the first time they happen, but their wonderfulness wanes with repetition. Just compare the first and last time your child said "Mama" or your partner said "I love you" and you’ll know exactly what I mean. When we have an experience hearing a particular sonata, making love with a particular person, watching the sunset from a particular window of a particular room—on successive occasions, we quickly begin to adapt to it, and the experience yields less pleasure each time. Psychologists call this habituation, economists call it declining marginal utility, and the rest of us call it marriage. But human beings have discovered two devices that allow them to combat this tendency: variety and time.

- p. 30

- There are many different techniques for collecting, interpreting, and analyzing facts, and different techniques often lead to different conclusions, which is why scientists disagree about the dangers of global warming, the benefits of supply-side economics, and the wisdom of low-carbohydrate diets. Good scientists deal with this complication by choosing the techniques they consider most appropriate and then accepting the conclusions that these techniques produce, regardless of what those conclusions might be. But bad scientists take advantage of this complication by choosing techniques that are especially likely to produce the conclusions they favour, thus allowing them to reach favoured conclusions by way of supportive facts. Decades of research suggests that when it comes to collecting and analyzing facts about ourselves and our experiences, most of us have the equivalent of an advanced degree in Really Bad Science.

- p. 164

- My friends tell me that I have a tendency to point out problems without offering solutions, but they never tell me what I should do about it. In one chapter after another, I've described the ways in which imagination fails to provide us with accurate previews of our emotional futures. I’ve claimed that when we imagine our futures we tend to fill in, leave out, and take little account of how differently we will think about the future once we actually get there. I’ve claimed that neither personal experience nor cultural wisdom compensates for imagination’s shortcomings. I’ve so thoroughly marinated you in the foibles, biases, errors, and mistakes of the human mind that you may wonder how anyone ever manages to make toast without buttering their kneecaps. If so, you will be heartened to learn that there is a simple method by which anyone can make strikingly accurate predictions about how they will feel in the future. But you may be disheartened to learn that, by and large, no one wants to use it.

- p. 223

- Nozick’s “happiness machine” problem is a popular among academics, who generally fail to consider three things. First, who says that no one would want to be hooked up? The world is full of people who want happiness and don’t care one bit about whether it is “well deserved.” Second, those who claim that they would not agree to be hooked up may already be hooked up. After all, the deal is that you forget your previous decision. Third, no one can really answer this question because it requires them to imagine a future state in which they do not know the very thing they are currently contemplating.

- p. 244

External links

[edit]- Daniel Gilbert blog at randomhouse.com