Enneads

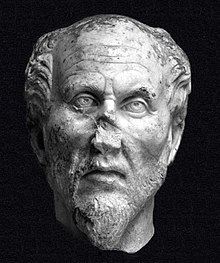

Appearance

The Enneads form the foundational textual collection of Neoplatonism. It is collection of writings of Plotinus, edited and compiled by his student Porphyry circa AD 270. There are 6 books consisting of 9 tractates (or treatises) each, adding up to a total of 54 tractates.

Quotes

[edit]- Gerson, Lloyd P., ed. (2018). The Enneads. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00177-0.

Ennead I

[edit]- How, then, can you see the kind of beauty that a good soul has? Go back into yourself and look. If you do not yet see yourself as beautiful, then be like a sculptor who, making a statue that is supposed to be beautiful, removes a part here and polishes a part there so that he makes the latter smooth and the former just right until he has given the statue a beautiful face. In the same way, you should remove superfluities and straighten things that are crooked, work on the things that are dark, making them bright, and not stop ‘working on your statue’ until the divine splendour of virtue shines in you, until you see ‘Self-Control enthroned on the holy seat’.

- 1.6.9

- We must, then, ascend to the Good, which every soul desires. If someone, then, has seen it, he knows what I mean when I say how beautiful it is. For it is desired as good, and the desire is directed to it as this, though the attainment of it is for those who ascend upward and revert to it and who divest themselves of the garments they put on when they descended. It is just like those who ascend to partake of the sacred religious rites where there are acts of purification and the stripping off of the cloaks they had worn before they go inside naked. One proceeds in the ascent, passing by all that is alien to the god until one sees by oneself alone that which is itself alone uncorrupted, simple, and pure, that upon which everything depends, and in relation to which one looks and exists and lives and thinks. For it is the cause of life and intellect. And, then, if someone sees this, what pangs of love will he feel, what longings and, wanting to be united with it, how would he not be overcome with pleasure? For though it is possible for one who has not yet seen it to desire it as good, for one who has seen it, there is amazement and delight in beauty, and he is filled with pleasure and he undergoes a painless shock, loving with true love and piercing longing. And he laughs at other loves and is disdainful of the things he previously regarded as beautiful.

- 1.6.7.1–19

Ennead II

[edit]- For the Difference in the intelligible world that produces the matter exists always. For this is the principle of matter, this and the first Motion. For this reason, Motion has been said to be Difference, since Motion and Difference were engendered together. The Motion and Difference that are proceeding from the first are indefinite, and they require the first to be made definite, and they are made definite when they have reverted to it. And matter, too, is previously indefinite insofar as it is different and not yet good and still unilluminated by the first. For if the light derives from the first, then what receives this light, prior to having received it, had always been without light, and it has light as something other than itself, if indeed the light derives from another.

- 2.4.5

Ennead III

[edit]- Since Intellect is a kind of sight and a sight that is seeing, it will be [like] a potency which is actualized. So, there will be its matter and its form, though matter here is intelligible. Besides, actual seeing, too, is twofold; before seeing it was one; then, the one became two and the two one. The completion and, in a way, perfecting of sight, then, comes from the sensible, but for the sight of Intellect it is the Good which completes it.

- 3.8.11

Ennead IV

[edit]- Often, after waking up to myself from the body, that is, externalizing myself in relation to all other things, while entering into myself, I behold a beauty of wondrous quality, and believe then that I am most to be identified with my better part, that I enjoy the best quality of life, and have become united with the divine and situated within it, actualizing myself at that level, and situating myself above all else in the intelligible world. Following on this repose within the divine, and descending from Intellect into acts of calculative reasoning, I ask myself in bewilderment, how on earth did I ever come down here, and how ever did my soul come to be enclosed in a body, being such as it has revealed itself to be, even while in a body?

- 4.8.1

Ennead V

[edit]

- Let us speak of this matter, then, in the following manner, calling to god himself, not with spoken words, but by stretching our arms in prayer to him in our soul, in this way being able to pray alone to him who is alone.

- 5.1.6

- Light, therefore, sees another light; therefore, it sees itself.

- 5.3.8

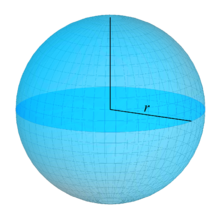

- Let there be formed in your soul, then, the image of a luminous sphere having all things in it, whether moving or stable, or some moving and some stable. Keeping this image, take another for yourself by abstracting the mass from it. Abstract, too, places and the semblance of the matter you have in yourself. Don’t try to take another sphere smaller than it in mass, but call on the god who made that of which you have a semblance, and pray for him to come. And he might come bearing his cosmos with all of the gods in it, being one and all of them, and each is all coming together as one, each with different powers, though all are one by that multiple single power. Rather, it is that one god who is all. For he lacks nothing, if all those gods should become what they are. They are all together and each is separate, again, in indivisible rest, having no sensible shape – for if they had, one would be in one place, and one in another, and each would not have all in himself. Nor do they have different parts in different places, nor all in the identical place, nor is each whole like a power fragmented, being quantifiable, like measured parts. It is rather all power, extending without limit, being unlimited in power. And in this way, the god is great, as the parts of it are all unlimited. For where could one say that he is not already present?

- 5.8.9

- In fact, one must not try to discover where it [the One] comes from. For there is not any ‘where’; it neither comes from nor goes anywhere, it both appears and does not appear. For this reason, it is necessary not to pursue it, but to remain in stillness, until it should appear, preparing oneself to be a contemplator, just like the eye awaits the rising sun. The sun rising over the horizon – the poets say ‘from Ocean’ – gives itself to be seen with the eyes.

- 5.5.8

Ennead VI

[edit]

- It is like someone who enters the inner sanctum and leaves behind the statues of the gods in the temple. And these are the first things one sees on leaving the inner sanctum after the vision within. The intimate contact within is not with a statue or an image, but with the One itself. The statue and the image are actually secondary visions, whereas the One itself is indeed not a vision, but another manner of seeing. It is self-transcendence, simplification, and surrender, an urging towards touch, a resting, concentration on alignment, if one is to have a vision of what is in the sanctum.

- 6.9.11

- If, then, one sees oneself having become this, then one has himself as a likeness of that; and if one moves from oneself, as from the image to the archetype, then he reaches ‘journey’s end’. And when one drops out of the vision, then one wakens virtue in oneself again; and seeing oneself ordered by virtues one is again uplifted by virtue, in the direction of intellect, and wisdom; and through wisdom, towards oneself. This is the way of life of gods, and divine, happy human beings, the release from everything here, a way of life that takes no pleasure in things here, the refuge of a solitary in the solitary.

- 6.9.11

- For at the time [of union], the seeing self neither sees nor discerns, nor imagines two things, but has, in a way, become another, and not oneself, nor does one belong to oneself in the intelligible world. One has come to belong to the Good, and has become one, like a centre touching a centre point. In the sensible world, too, when the circles come together they are one, but when they separate they are two. This is what we mean now when we say ‘different’. For this reason, the vision is hard to make out. For how can someone report that he has seen something different, when he did not see something different in the intelligible world when he had his vision, but rather something united to himself?

- 6.9.10