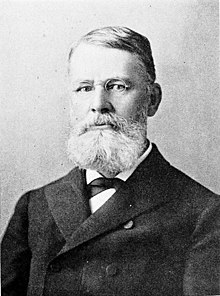

George Holmes Howison

George Holmes Howison (29 November 1834 – 31 December 1916) was an American philosopher, who established the philosophy department at the University of California, Berkeley and held the position there of Mills Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy and Civil Polity.He also founded the Philosophical Union, one of the oldest philosophical organizations in the United States.

Howison’s philosophy is set forth almost entirely in his volume entitled, The Limits of Evolution, and other essays, illustrating the metaphysical theory of personal idealism. Scrutinizing the idea of evolution that had come to the fore, he proved not only that no Person can be wholly “the product of ‘continuous creation’”, evolution, but went on also to show that, rooted in the very same (a priori) reason, fulfilled philosophy necessarily ends in the “Vision Beatific”, “that universal circle of spirits which, since the time of the stoics, has so pertinently been called the City of God”.

Friends and former students of Howison established the Howison Lectures in Philosophy in 1919. Over the years, the lecture series has included talks by distinguished philosophers such as Michel Foucault and Noam Chomsky.

Quotes

[edit]The Limits of Evolution, and Other Essays, Illustrating the Metaphysical Theory of Personal Ideaalism (1905)

[edit]Italics and Capitalization in original

Dedication

[edit]- To All

- Who Feel a Deep Concern

- For

- The Dignity of the Soul

- p.v

Preface to First Edition

[edit]- “Instead of any monism, these essays put forward a Pluralism: they advocate an eternal or metaphysical world of many minds, all alike possessing personal initiative, real self-direction, instead of an all-predestinating single Mind that alone has real free-agency.”

- p.x-xi

- “Time and Space, and all that both "contain," owe their entire existence to the essential correlation and coexistence of minds. This coexistence is not to be thought of as either their simultaneity or their contiguity. It is not at all spatial, nor temporal, but must be regarded as simply their logical implication of each other in the self-defining consciousness of each. And this recognition of each other as all alike self-determining, renders their coexistence a moral order.”

- p.xiii

- “The members of this Eternal Republic have no origin but their purely logical one of reference to each other, including thus their primary reference to God. That is, in the literal sense of the word, they have no origin at all — no source in time whatever. There is nothing at all, prior to them, out of which their being arises; they are not "things" in the chain of efficient causation. They simply are, and together constitute the eternal order.”

- p.xiv

Preface to Second Edition

[edit]- “Thus the world of minds, as the sole world of Ends presupposed in all moral responsibility, the world of ultimate and standard Objects, becomes at one and the same stroke the warranting foundation of knowledge and of good-will alike: to refuse good-will is to violate the primary principle of each mind's own existence, and is therefore to convict oneself, in one and the same act, of irrationality and folly as well as of indifference or of ill-will.”

- p.xxxvii

- “The achievement of this task depends on attaining to the true distinction, the real relation, between the two orders of existence which to ordinary and uncritical reflexion — usual common-sense — appear as two substances, so called, or species of substance, and are named "mind" and "matter." What is to be shown is, that this common-sense contrast, read off as a hard-and-fast dualism, is not intelligibly interpretable except as the distinction between two aspects of one and the same total nature in the beings that possess it”

- p.xlvi

The Limits of Evolution

[edit]- “For the very quality of personality is, that a person is a being who recognises others as having a reality as unquestionable as his own, and who thus sees himself as a member of a moral republic, standing to other persons in an immutable relationship of reciprocal duties and rights, himself endowed with dignity, and acknowledging the dignity of all the rest.”

- p.7

- “The agnostic position, the largest historic view of philosophy would say, is an unwarrantable arrest of the philosophic movement of reason; and its unjustifiable character appears in the fact, which can clearly be shown, that it involves at once a petitio and a self-contradiction.”

- p.15-6

- “The question whether we have not some knowledge independent of any and all experience — whether there must not, unavoidably, be some knowledge a priori, some knowledge which we come at simply by virtue of our nature — is really the paramount question, around which the whole conflict in philosophy concentrates, and on the decision of which the settlement of every other question hangs. To cast the career of a philosophy upon a negative answer to it, as if this were a matter of course, — which the English school from Hobbes onward has continually done, — is to proceed not only upon a petitio, but upon a delusion regarding the security of the road.”

- p.17

- “He [Kant] suggested that experience may be not at all simple, but always complex, so that the very possibility of the experience which seems to the empiricist the absolute foundation of knowledge may depend on the presence in it of a factor that will have to be acknowledged as a priori. This factor issues from the nature of the mind that has the experience, and introduces into experience all that distinguishableness, that arrangedness, and that describable form, without which it could not be conceived as apprehensible or intelligible, that is, as an experience at all.”

- p.17-8

- “Here, in seeing that Final Cause — causation at the call of self-posited aim or end — is the only full and genuine cause, we further see that Nature, the cosmic aggregate of phenomena and the cosmic bond of their law which in the mood of vague and inaccurate abstraction we call Force, is after all only an effect.”

- p.39

- “Throughout Nature, as distinguished from idealising mind, there reigns, in fine, no causation but transmission.”

- p.39

- “Here we reach the demonstration that evolution not only is a fact, and a fact of cosmic extent, but is a necessary law a priori over Nature. But we learn at the same time, and upon the same evidence, that it cannot in any wise affect the a priori consciousness, which is the essential being and true person of the mind; much less can it originate this. On the contrary, we have seen it is in this a priori consciousness that the law of evolution has its source and its warrant. Issuing from the noumenal being of mind, evolution has its field only in the world of the mind's experiences, — "inner" and "outer," physical and psychic; or, to speak summarily, only in the world of phenomena. But there, it is indeed universal and strictly necessary.”

- p.40-1

- “It is just in thinking all these elements in an active originating Unit-thought, or an "I," that the essential and characteristic nature of man or any other real intelligence consists. Such an originating Unit-thinking, providing its own element-complex of primal thoughts that condition its experience, and that thus provide for that experience the form of a cosmic Evolutional Series, is precisely what an intelligent being is. Thus creatively to think and be a World is what it means to be a man. To think and enact such a world merely in the unity framed for it by natural causation, is what it means to be a "natural" man; to think and enact it in its higher unity, its unity as framed by the supernatural causation of the Pure Ideals, supremely by the Moral Ideal, is what it means to be a "spiritual" man, a moral and religious man; or, in the philosophical and true sense of the words, a supernatural being — a being transcending and yet including Nature, not excluding or annulling it.”

- p.47

- “Plain in the doctrinal firmament of every Christian, clear like the sun in the sky, should shine the warning: Unless there is a real man underived from Nature, unless there is a spiritual or rational man independent of the natural man and legislatively sovereign over entire Nature, then the Eternal is not a person, there is no God, and our faith is vain.”

- p.53

- “The professed Philosophy of Evolution is not an adult philosophy, but rather a philosophy that in the course of growth has suffered an arrest of development.”

- p.53-4

- “Fulfilled philosophy vindicates our faith in the Personality of the Eternal Ideal, in the reality of God, by vindicating the reality of man the Mind, and exhibiting his legislative relation to Nature and thence to evolution. It thus secures a stable footing for freedom, and for immortality with worth, and thereby for the existence of the Living God who is Love indeed, because the Inspirer of an endless progress in moral freedom.”

- p.54

- “Let men of science keep the method of science within the limits of science; let their readers, at all events, beware to do so. Within these limits there is complete compatibility of science with religion, and forever will be.”

- p.54-5

Modern Science and Pantheism

[edit]- “We hear constantly, too, that theism, to be real, must teach that there is a being who is truly God: that the Principle of existence is a Holy Person, who has revealed his nature and his will to his intelligent creatures, and who superintends their lives with a providence which aims to secure their obedience to his will as the only sufficient condition of their blessedness.”

- p.58

- “Thus, by mere confusion of thought, or by inability to rise above conceptions couched in terms of space and time, the original theistic formula — which in its contrasting of theism against deism and pantheism is unobjectionable, and correct enough so far as it goes — is brought in the end to contradict its own essential idea.”

- p.60-1

- “For genuine omniscience and omnipotence are only to be realised in the control of free beings, and in inducing the divine image in them by moral influences instead of metaphysical and physical agencies: that is, by final instead of efficient causation.”

- p.65

- “No mind can have an efficient relation to another mind; efficiency is the attribute of every mind toward its own acts and life, or toward the world of mere "things " which forms the theatre of its action; and the causal relation between minds must be that of ideality, simply and purely.”

- p.74

- “Not in its statement of God as the All-in-all, taken by itself, but in its consequent denial of the reality of man — his freedom and immortal growth in goodness — is it that pantheism betrays its insufficiency to meet the needs of the human spirit.”

- p.77

- “But so long as human nature is what it is, so long as we are by essence prepossessed in favour of our freedom and yearn for a life that may put death itself beneath our feet, and with death imperfection and wrong, so long will our nature reluctate, so long will it even revolt, at the prospect of having to accept the doctrine of pantheism; so long shall we instinctively draw back from that vast and shadowy Being which, be it conscious or unconscious or simply the Unknowable, must for us and our highest hopes be verily the Shadow of Death”

- p.77-8

- “A pantheistic edict of science would only proclaim a deadlock in the system and substance of truth itself, and herald an implacable conflict between the law of Nature and the law written indelibly in the human spirit.”

- p.78

- “To present universal Nature as the deep in which each soul with its moral hopes is to be engulfed, is to transform existence into a system of radical and irremediable evil, and thus to make genuine religion impossible;”

- p.79-80

- “Let us not fail to realise that pantheism means, not simply the all-pervasive interblending and interpenetration of God and other life, but the sole causality of God, and so the obliteration of freedom, of moral life, and of any immortality worth the having; in a word, of the true being of God himself.”

- p.81

- “With regard now, first, to the argument drawn with such apparent force purely from the method of natural science, it will be plain to a more scrutinising reflexion, that shifting from the legitimate disregard of a supersensible Principle — a disregard in which the empirical method is entirely within its right — to the denial or the doubt of it because there is and can be no scientific evidence for it, is in fact an abuse of the scientific method, an unwarrantable extension of it to decisions lying by its own terms beyond its reach.”

- p.95

- “Natural science must therefore, in truth, be declared silent on this question of pantheism; as indeed it is, and from the nature of the case must be, upon all theories of the supersensible alike — theistic, deistic, atheistic, pantheistic. Natural science has no proper concern with such theories.”

- p.97

Later German Philosophy

[edit]- “On the other hand, it would be materially unjust to take leave of Hartmann and Schopenhauer without emphatically acknowledging the service they have both rendered by so completely unveiling the pessimism latent in any theory that represents the Eternal as impersonal.”

- p.121

- “As to our real knowledge, he [Lange] has now shown (1) that a bare thing-in-itself, a thing out of all relation to minds, does not exist; (2) that, even as notion, it is a self-contradiction, something whose sphere is solely within consciousness putting itself as if it were beyond it; (3) that, in spite of this, we continue, and must continue, to accept this illusion, which compels us to limit our knowledge to experience and to renounce all claims to its being absolute.”

- p.168

- “Therefore, precisely by the investigation through which Lange has led us, we are now in the position to assure ourselves of the reality, the absoluteness in quality, of our human intelligence.”

- p.169-70

- “From the Kantian doctrine of the a priori carried to its genuine completion, as we have now seen it, we infer that the objects which present themselves in course of the normal and critical action of human consciousness are all that objects as objects can be; that beyond or beneath what completed human reason (moral, of course, as well as perceptive and reflective) finds in objects and their relations, or can and will find, there is nothing to be found; that our universe is the universe, which exists, so far as we know it, precisely as we know it, and indeed in and through our knowing it, though not merely by that. To state the case more technically, the cognition belonging to each mind is the indispensable condition of the existence of reality, though it is not the completely sufficient condition. If one asks, What then is this sufficient condition, the answer is, The consensus of the whole system of minds, including the Supreme Mind, or God.”

- p.170

- “The process which has led us to this result, and which might justifiably be called a Critique of all Scepticism, yields also the final impossibility of materialism in a still clearer way than we noticed before. We saw, some distance back, that the actual of sense could by no possibility be the source of consciousness, being, on the contrary, its mere phenomenon — its mere externalised presentation (picture-object) originated from within. But the hypothetical potential of sense, the assumed subsensible substance called matter, we have now seen to be precisely that self-contradiction talked of as the physical thing-in-itself, and it therefore disappears from the real universe along with that illusion. We have, then, a definitive Critique of all Materialism.”

- p.170-1

- “By the path into which Lange has led us we therefore ascend from the agnostic-critical standpoint to the higher and invigorating one of a thorough, all-sided, and affirmative idealism.”

- p.171

- “It is plain, of course, that any proof of this depends upon the validity of the doctrine of a priori cognition; only by our proved possession of such cognition can there be any evidence that we are self-active realities. It is in this reference noteworthy, therefore, that Lange, as defender of agnosticism, sees he cannot afford to admit the theory upon which alone cognition strictly a priori can be established.”

- p.175

- “For an induction, despite its formal generality, is always in its own value a particular judgment, always comes short of full universality; whereas, to establish the apriority of an element, we must show it to be strictly universal, or, in other words, necessary.”

- p.176

- “True is it indeed, that without an Abiding and Active in us the transitory and sensible is impossible. As the case has been forcibly put in a saying that deserves to become classic, "Our unconditioned universality is the ground of our existence," — its ground, that is, at once its necessary condition and its sufficient reason.”

- p.178

The Art-Principle as Represented in Poetry

[edit]- “As poetry is a species of art, its essential principle must be a specific development of the principle essential to all art; and it will merely remain for us to determine what the specific addition is, which the peculiar conditions of the poet's art make to the principle of art in general.”

- p.182

- “That is, art is not the cancelling of the actual and imperfect, and the putting in its place of a vague and fanciful perfection that is only an illusory abstraction after all; it is the transfiguring of the actual by the ideal that is actually immanent in it. The actual hides in itself an ideal that is its true reality and destination, and this hidden ideal it is the function of art to reveal.”

- p.183

- “And as the ideal in the whole of Nature moves in an infinite process toward an Absolute Perfection, we may say that art is in strict truth the apotheosis of Nature. Art is thus at once the exaltation of the natural toward its destined supernatural perfection, and the investiture of the Absolute Beauty with the reality of natural existence. Its work is consequently not a means to some higher end, but is itself a final aim; or, as we may otherwise say, art is its own end. It is not a mere recreation for man, a piece of by-play in human life, but is an essential mode of spiritual activity, the lack of which would be a falling short of the destination of man. It is itself part and parcel of man's eternal vocation.”

- p.183-4

- “Only the most experienced judges can recognise a work of the highest order at sight; even to them the proper realisation of its true compass and depth comes only through repeated examination and careful study; while the ordinary examiner finds the first impression of the greatest works ineffective or even disappointing. Work of genius demands for its swift recognition an answering genius in the beholder; in lack of it, there must be a patient teachableness, that awaits the slow self-revelation of greatness.”

- p.186

- “The doctrine which thus comes to light, that in art man not only shares literally in the creative office of God, but enriches Nature with new members that express its divine Ground in a still higher form, will seem to many overbold — extravagant and irreverent. But its advocates are neither few nor inconsiderable; it is supported by the greatest names.”

- p.188-9

- “Art in its unblemished nature, like religion and the search for truth, is thus literally a sacrament. The artist's calling and genius are sacred, and the men of old spoke with strict accuracy when they called the poet holy, and directed that he be venerated as a prophet.”

- p.199-200

- “Art will never get its own, nor do its proper work in the discipline of life, until the sense of its sacred character comes once more into the general judgment, and masses of men look upon it as the few great spirits have looked who have been its true masters and interpreters”

- p.200

- “The proper form of science is explanation and argument, and the proper form of religion and morality is exhortation and command; but that of art is simply the directest embodiment of its theme as the theme itself requires. Assured that the theme is compatible with the ideal nature of art, the artist knows that it will justify itself and work its own work, if it can only find expression in its natural embodiment.”

- p.201-2

- “No, nothing short of the creative principle of imagination gives the fine arts their specific quality—the principle that creates for the sake of creating, for the sake of giving free course to that imagination which is not only an essential but the guiding factor in the supersensible being of man, and which not only founds for him the world of religion and of science, as well as that of art, but is the constructive and developing principle of the universe itself.”

- p.206

- “Poetry, finally, is the form of art where not only are the unities of time, place, and action freed from the restrictive bounds of the single instant, the single spot, the single simple transaction, but the medium of embodiment is thought itself, with its completely articulate utterance in language. Here the very source of the ideal view of the world, the very origin of the creative artistic impulse, becomes the material and the instrument of its own purpose, the executor of its own will. The scope of the creative faculty is therefore the utmost conceivable, and poetry rightfully takes the highest place as the art of the greatest possibilities — the art, indeed, of an all-inclusive compass, as at length completely self-supplying and self-directing.”

- p.210

The Right Relation of Reason to Religion

[edit]- “To the question, What is the right relation between reason and religion, you will now understand me to answer, It is that reason should be the source of which religion is the issue; that reason, when most itself, will unquestionably be religious, but that religion must for just that cause be entirely rational; that reason is the final authority from which religion must derive its warrant, and with which its contents must comply; that all religious doctrines and instrumentalities, all religious practices, all religious institutions, and all records of religion, whether in tradition or in scripture, must alike submit their claims at the bar of general human reason, and that only those approved in that tribunal can be regarded as of weight or of obligation; in short, that the only real basis of religion is our human reason, the only seat of its authority our genuine human nature, the only sufficient witness of God the human soul. Reason, I shall endeavour to show, is not confined to the mastery of the sense-world and the goods of this world only, but does cover all the range of being, and found and rule the world eternal; it is not merely natural, it is also spiritual; it is itself, when come to itself, the true divine revelation.”

- p.224-5

- “In any proposed external communication from God, the channels of human faculty are never to be got rid of; so, if they do not in their own native quality constitute divine vouchers, they must operate as barriers to any communication with God. Of God, who is essentially supersensible, there can be no such thing as a presentation directly to our senses; and all belief that sensible facts mean his real presence must rest at last on inferential judgments of our reason, while these will be nothing but self-continuing circles, worthless for evidence, unless our reason is granted to have in itself the real revelation of what accords with the Divine mind. An absolutely direct utterance of God in the external world, evident strictly in itself, is thus upon close examination unintelligible and unthinkable. Yet this is what is implied in a consistent doctrine of Authority.”

- p.240-1

- “But what I do mean is, that wherever the principle of Authority has entered and operated in historic Christianity, it has interfered with the free expression and development of that teaching and spirit which is most specifically characteristic of Jesus when his mind and work are viewed, as they must be, in the light of the comparative history of religious thought. I mean that so far as the various Christian bodies which adhere to the principle of Authority have succeeded in displaying the spirit of Christ, and unconsciously keeping its inmost secret still alive in the world, they have done so, not because of the doctrine of Authority, but in spite of it,”

- p.242-3

- “To the great Greek teachers, even to Socrates, as it still is practically to us all, this one and only truth of living religion was more or less but a distant thought, summoned into direct consciousness at intervals by a reflective effort, and brought to bear upon conduct amid the clamours of our animal being. To Jesus, on the contrary, it is an ever-present perception, like light to vision, like space to our movements, like time to our projects in life.”

- p.244

- “All souls are to strive after just that form of life with each other in which none will employ toward another any method of constraint, but will rely upon the moral action of the powers in the others' souls, just as God eternally does.”

- p.250

- “The aim, the only ultimate aim, the ideal of a society of minds, is this moral reliance on the inherent moral freedom of all spirits, guided by the contemplation of its perfect fulfilment in the Supreme Soul, or God, and inspired by his boundless love beheld and therefore felt by all.”

- p.251

- “His [Christ’s] point of view, of the literal divine-son ship of every lowliest and most sinful and sinning spirit, committed him logically to the assertion of the implicit equality of all spirits with each other, far as concerns their moral powers and destination no matter what their actual and contingent state; and also of their potential equality with God. His doctrine may well be summarised in the consecrated phrase, usually applied only to himself, "The son of man is the son of God."”

- p.251

- “The aim of such a religion is not merely to "glorify God"; rather, it is to glorify all souls, as all in the image of God; to glorify them by fulfilling for every one of them its vocation to repeat in a new way the life of universal love that is the life of God, and thus to attain, through the universal greatening, such a real glorification of God as other forms of religion seek after in vain.”

- p.255

- “Accordingly we may explicate the new doctrine of Jesus into these three truths: (1) That God is the perfect Person, the central member in the universal society actuated by love; (2) that the soul is immortal; (3) that it is free, both in the sense of being the responsible author of all its acts, and in the sense that its fund of ultimate resources is equal to fulfilling its duty to love as God loves.”

- p.256-7

- “The true love wherewith God loves other spirits is not the outpouring upon them of graces which are the unearned gift of his miraculous power; it is the love, on the contrary, which holds the individuality, the personal initiative, of its object sacred. As the true father desires that the son who, after him, is to be the head of the family shall have a method and policy of his own, by which the honours of the line shall be increased by new contributions, so he who is the Father of Spirits will have his image brought forth in every one of his offspring by the thought and conviction of each soul itself.”

- p.257

- “The moral government of God, springing from the Divine Love, is a government by moral agencies purely. It relies utterly on the operation of the powers native to the soul itself; and leaving aside all the juridical enginery of reward and punishment, it lets his sun shine and his rain fall alike on the just and on the unjust, that the cause of God may everywhere win simply upon its merits.”

- p.258

- “At the core, what Jesus did was to reform the conception of God in the interest of the absolute reality and the moral freedom of men. With this what can be more discordant, what more hostile to it, than the attempt to establish by an appeal to declarative authority doctrines that either contradict the human reason or have no witness from it?”

- p.259

- “In view of all the foregoing reasons, I cannot but think the case conclusive, that neither form of the Doctrine of Authority can be maintained. We should abandon, as consistent thinkers, and still more as consistent Christians, the imperative authority both of Church Tradition and of Scripture. There is nothing left, then, but the Doctrine of Reason — the Method of Conviction as the only real method of determining religious belief and practice, resting on the use of the human rational powers taken in their entire compass.”

- p.260

Human Immortality: its Positive Argument

[edit]- “This ideal theory of the true and real being that hides behind phenomena, Professor James, I repeat, puts forward only as a possible hypothesis, to point and emphasise his contention that "when we think of the law that thought is a function of the brain, we are not required to think of productive function only; we are entitled also to consider permissive or transmissive function."”

- p.282

- “Judged by the light of this "vale of tears" alone, there is no evidence that good will toward us is the chief or the permanent aim of the eternal Lord or lords.”

- p.295

- “When we say that the mind is a function of the brain, we are therefore to understand that in exact scientific truth we can mean nothing more than this: That physical and physiological changes go on, seriatim, side by side with changes in psychic experience; or vice versa, that psychic changes run parallel, pari passu, with physiological changes in the brain and the other neural tissues.”

- p.295

- “Concomitance simply means, at last, that both series of changes are connected with some cause, distinct from either, which is the secret of both.”

- p.296

- “Our real experiences, day by day and moment by moment, are so intrinsically organised and definite, it does not at first occur to us that the principles which organise and define them, rendering them intelligible, and consciously apprehensible, are and must be the spontaneous products of the mind's own action.”

- p.297

- “But when we have reached this conclusive conviction that the roots of our experience and our experimental knowledge are parts of our own spontaneous life, we then readily come to see, further, that the system of our several elements of consciousness a priori is precisely what we must really understand by our unifying or enwholing self, — is exactly what we try to express when we say we have a soul, and that this soul possesses real knowledge; that is, a hold upon eternal things. The realm of the eternal, in short, then becomes for us just the realm of our self-active intelligence; and this it is which, if we can show its reality in detail, will prove to be the clue to our immortal being.”

- p.298

- “We return, then, to the strict concomitance of the two series, as all that can in exact science be meant by the functional relation between the brain and the sense-perceptive consciousness.”

- p.299

- “In the place, then, of death's ending us, — death, but one item in the being of the natural world, the whole of which is conditioned upon our central self-consciousness,—we arrive at the settled and logically immovable conception that we are ourselves the changeless ground of that transition in experience into which death thus gets interpreted.”

- p.306

- “For the ultimate and real meaning of the argument is, that a soul or mind or person, purely as such, is itself the fountain of its percipient experience, and so possesses what has been happily named "life in itself." Proof of the presence in us of a priori or spontaneous cognition, then, is proof of just this self-causative life.

- A world of such individual minds is by the final implications of this proof the world of primary causes, and every member of it, secure above the vicissitudes of Time and Space and Force, is possessed of a supertemporal or eternal reality, and is therefore not liable to any lethal influence from any other source. Itself a primary cause, it can neither destroy another primary cause nor be destroyed by any. The objector who would open the eternal permanence of the soul to doubt, then, must assail the proofs of a priori knowledge; for so long as these remain free from suspicion, there can be no real question as to what they finally imply. The concomitance of our two streams of experience, the timed stream and the spaced stream, raised from a merely historical into a necessary concomitance by the argument that refers it to the active unity of each soul as its ground, becomes the steadfast sign and visible pledge of the imperishable self-resource of the individual spirit.”

- p.307-8

- “By their very ideality they conclusively refer themselves to our spontaneous life: nothing ideal can be derived from experience, just as nothing experimental is ever ideal.”

- p.309

- “The worth-imparting ideals, then, are, by virtue of the active and indivisible unity of our person, in an elemental and inseparable union with the root-principles of our perceptive life. Proof of our indestructible sourcefulness for such percipient life is therefore ipso facto proof that these ideals will reign everlastingly in and over that life. Once let us settle that we are inherently capable of everlasting existence, we are then assured of the highest worth of our existence as measured by the ideals of Truth, of Beauty, and of Good, since these and their effectually directive operation in us are insured by their essential and constitutive place in our being.”

- p.309-10

- “'Tis but a surface-view of human nature which gives the impression that the argument to immortality from our a priori powers leads to nothing more than bare continuance. What it really leads to, is the continuance of a being whose most intimate nature is found, not in the capacity of sensory life, but in the power of setting and appreciating values, through its still higher power of determining its ideals. For such a nature to continue, is to continue in the gradual development of all that makes for worth.”

- p.310

- “And thus the easy argument of exhibiting the least conditions sufficient for experience, so like a simpleton in its seeming clutch at the thin surface of things, carries in its subtle heart the proof of an imperishable persistence in all that gives life meaning and value.”

- p.312

The Harmony of Determinism and Freedom

[edit]- “So the conciliability of determinism and freedom depends on the fact, if this be a fact, that determinism simply means definiteness (instead of constraining foreordination), while freedom means (instead of unpredictable whim) action spontaneously flowing from the definite guiding intelligence of the agent himself. In short, the desired harmony will fail unless the determinism and the freedom are both alike defined in terms of the one and identical definiteness of the rational nature; but it will be secured if they can be so defined, and are.”

- p.320

- “Therefore, further, for a being who involves such a finite world, the condition of his freedom in it, the condition indispensable but at the same time sufficient, is that his world shall indeed be his; shall be of him, not independent of him; shall be embraced under his causal life, not added to it from elsewhere as a constricting condition; shall be, in fine, a world of phenomena, — states of his own conscious being, organised by his spontaneous mental life, — and not a world of "things-in-themselves."”

- p.323

- “So the free being, as self-determined and taken in his whole contents, is definite in both senses of the word: he defines himself, and thus has the definiteness of unpredestination; he defines his empirically real world of things, and thus adds to himself a field of action having the definiteness of predestination, — in a manner arms himself with it, inasmuch as he transcends and controls it.”

- p.324

- “Our result thus far is, that determinism and freedom, when justly thought out, are in idea entirely reconcilable. Determinism proves to need no fatalistic meaning, but to be, possibly enough, simply the definite order characteristic of intelligence; while so far from freedom's being indeterminism, chance, or caprice, these are seen to be incompatible with it, and freedom proves to be, like determinism, the spontaneous definiteness of active intelligence.”

- p.324

- “In fine, a condition of our making freedom possible in a world ordered by the rigour of natural law is that we accept an idealistic philosophy of Nature: the laws of Nature must issue from the free actor himself, and upon a world consisting of states in his own consciousness, a world in so far of his own making.”

- p.325

- “This principle of cosmic subjection has by theists always been realised with reference to God: the natural world, they are always telling us, however full of laws to which other conscious beings are subject, is completely subject to the mind and will of God, and its laws are imposed upon it from his mind in virtue of his creating it. What we now learn, and need to note, is that this is just as true of any other being who can be reckoned free. If men are free, then, they must be taken as being logically prior to Nature; as being its source rather than its outcome; as determining its order instead of being determined by this.”

- p.325

- “This exaltation of man over the entire natural world, however, though easily shown to accord with the teaching of Jesus, and to be clearly prefigured in it, is nearly antipodal to ordinary notions, to the current popular "philosophy" assumed to be founded on science, and to much of traditional theology. But by this fact we must not be disturbed, if we mean to be in earnest about human freedom and human capability of life really moral and religious. And the next step in our inquiry will reinforce this "divinising of the human " very decidedly.”

- p.326

- “It might pertinently be said that determinism and freedom are of course compatible enough when they are merely viewed as the two reciprocal aspects of self-activity in a single mind, but that the real difficulty is to reconcile the self-determinisms in different free minds.”

- p.326-7

- “If the solution is possible, then, it will only be so by the fact that, on the one hand, perfect intelligence or reason is the essence of God, — who therefore determines all things, not by compulsion, but only in his eternal thought, which views all real possibilities whatever; and that, on the other hand, the spirit other than God also has its freedom in self-active intelligence. This granted, the range of its possibilities is precisely the range of reason again, and so is to God perfectly knowable and known, since it harmonises in its whole with the Eternal Thought that grasps all possibilities, though it is not at all predestined by this”

- p.327

- “Solution of this knot by any other conceptions of freedom and determinism than these, there plainly can be none. But the solution is secure if God and other spirits are alike rational, simply by their inner and self-active nature; in other words, if the solution is by spontaneous harmony from within, and not by productive and executive domination from without”

- p.327-8

- “Before it can be said, then, that human freedom and the absolute definiteness of God as Supreme Reason are really reconciled, we must have found some way of harmonising the eternity of the human spirit with the creative and regenerative offices of God. The sense of their antagonism is nothing new. Confronted with the race-wide fact of human sin, the elder theology proclaimed this antagonism, and solved it by denying to man any but a temporal being; quite as the common-sense of the everyday Philistine, absorbed in the limitations of the sensory life, proclaims the mere finitude of man, and is stolid to the ideal considerations that suggest immortality and moral freedom, rating them as day-dreams beneath sober notice, because the price of their being real is the attributing to man nothing short of infinity. "We are finite! merely finite!" is the steadfast cry of the old theology and of the plodding common realist alike; and, sad to say, of most of historic philosophy too. And the old theology, with more penetrating consistency than the realistic ordinary man or the ordinary philosophy, went on to complete its vindication of the Divine Sovereignty from all human encroachment by denying the freedom of man altogether.”

- p.330-1

- “Human finitude as the summary of human powers, with its consequent complete subjection to Divine predestination, is inwrapt in this conception of Divine causation as causation by efficiency; and there can be no way of supplementing this finitude by the infinity (i.e. freedom) required by a moral order, except by dislodging this view of creation and regeneration.”

- p.331-2

- “Especially must we find a substitute for creation by fiat, or efficient causation. For no being that arises out of efficient causation can possibly be free”

- p.332

- “Either, then, we must carry out our modern moral conception of God's nature and government into a conception of creation that matches it — a conception based on that eternity (or intrinsic supertemporal self-activity) of man which alone can mean moral freedom — or else, in all honesty and good logic, we ought to travel penitently back to a Calvinism, a Scotism, an Augustinianism, of the so-called "highest" type. Then we would view man as a "creature" indeed. We should have to accept him as a being belonging to time only, with a definite date of beginning, though lasting through unceasing ages, if that could indeed then be. We should have to surrender all freedom for him as a delusion. In effect, with this conception of creation, we must return to an unmitigated Predestinationism. Nor may this stop short of foreordination to Reprobation as well as to Election — a foreordination not simply "supralapsarian," but precedent to creation itself. The separation of the Sheep from the Goats must be from "before the foundation of the world," and the Elect must be created "unto life everlasting," while the reprobate are created "unto shame and everlasting contempt."”

- p.333-4

- “Much less could regeneration, the bringing-on of voluntary repentance and genuine reformation in the soul, be by any sort of efficient causality,—a truth to which modern theology has evidently for some time been alive, as its forward movement is keyed upon the increasing recognition of the metaphor in the name. These thoughts, however incontrovertible they may be, are no doubt staggering thoughts, so much are we of old habituated to calling regeneration the "work" of the Holy Spirit, and to naming man the "creature" of God, and God his "maker." Still, staggering though they be, they must be true if human freedom is to be a fact; and that human freedom is to be a fact, the modern conscience, quickened by the very experience of the Christian spirit itself, firmly declares, having now apprehended that otherwise there is no justice in human responsibility, and then no moral government, but only government edictive and compulsory; and then — no personal God, no true God, at all!”

- p.334-5

- “We are not to evade, then, the eternity of free beings that is implied in any serious demand for freedom. If the souls of men are really free, they coexist with God in the eternity which God inhabits, and in the governing total of their self-active being they are of the same nature as he, — they too are self-put rational wholes of self-conscious life. As complete reason is his essence, so is reason their essence—their nature in the large—whatever may be the varying conditions under which their selfhood, the required peculiarity of each, may bring it to appear. Each of them has its own ideal of its own being, namely, its own way of fulfilling the character of God; and its self-determining life is just the free pursuit of this ideal, despite all the opposing conditions by which it in part defines its life. Moreover, since this ideal, seen eternally in God, is the chosen goal of every consciousness, it is the final — not the efficient—cause of the whole existing self. All the being of each self has thus the form of a self-supplying, self-operating life; or, in the phraseology of the Schoolmen and Spinoza, each is causa sui. This is what its "eternity" exactly means.”

- p.338-9

- “The tragic situation of the modern liberalised Christian mind is just that. Having accepted with fervour the moral ideal as the Divine ideal, it still remains in bondage to the old mechanical conception of the great Divine operations called Regeneration and Creation. These it still thinks, at bottom, under the category of efficient causality. It takes their names literally, in accordance with the etymology, and thus the names themselves help the evil cause of prolonging conceptions that are hostile to the dearest insights of the moral spirit quickened in the school of Christ. Eminently is this true in the case of creation, into the current conception of which, so far as I can see, there as yet enters no gleam of the change that must be made if our relations to God in the basis of existence are to be stated consistently with the independence we must have of him in the moral world. This lack of a moral apprehension of creation is as characteristic, too, of historic philosophy as it is of historic theology, or even of ordinary opinion.”

- p.342-3

- “I am to show you, too, that in the world of eternal free-agents, the Divine offices called creation and regeneration not only survive, but are transfigured; that in this transfiguration they are merged in one, so that regeneration is implicit in creation, and becomes the logical spring and aim of creation, while creation itself thus insures both generation and regeneration—the existence of the natural order within the spiritual or rational, and subject to this, and the consequent gradual transformation of the natural into the image of the spiritual: a process never to be interrupted, however devious, dark, or often retrograde, its course may be. I am to show you all this by the light of Final Cause, which is to take the place of the less rational category of Efficient Causation, since—let it be repeated — this last cannot operate to sustain moral relationship, and since moral values, measured in real freedom, are for the conscience and the new theology the measure of all reality.”

- p.350-1

- “In this fact we have reached the essential form of every spirit or person — the organic union of the particular with the universal, of its private self-activity in the recognition of itself with its public activity in the recognition of all others. That is, self-consciousness is in the last resort a conscience, or the union of each spirit's self-recognition with recognition of all. Its self-definition is therefore definite, in both senses of the word: it is at once integral in its thorough and inconfusible difference from every other, and yet it is integral in terms of the entire whole that includes it with all the rest. Thus in both of its aspects — and both are essential to it — in a commanding sense it excludes alternative, and there is universal determinism, that is, universal and stable definiteness, just because there is universal self-determination, or genuine freedom. But this universal self-defining implies and proclaims the universal reality, the living presence in all, of one unchangeable type of being — the self-conscious intelligence; and this, presented in all really possible forms, or instances, of its one abiding nature.”

- p.353-4

- “The created, as well as the Creator, creates. Self-activity that recognises and affirms self-activity in others, freedom that freely recognises freedom, is universal: every part of this eternally real world is instinct with life in itself. Each lives in and by free ideality, the active contemplation of its own ideal; and this ideal embraces, as its essential, prime, and final factor, the one Supreme Ideal.”

- p.356

- “Love, too, now has its adequate definition: it is the all-directing intelligence which includes in its recognition a world of beings accorded free and seen as sacred, — the primary and supreme act of intelligence, which is the source of all other intelligence, and whose object is that universal circle of spirits which, since the time of the Stoics, has so pertinently been called the City of God. Its contemplation of this sole object proper to it was fitly named by Dante and the great scholastics the Vision Beatific.”

- p.361

- “This empirical volition seduced by the vision of the sense-world, be this sensual or malicious, or be it ever so much raised above the brutal,—this willingness to stay where one temporally is, to accept the actual of experience for the ideal, the mere particular of sense for the universal of the spirit, the dead finite for the ever-living infinite, the world for God,—this is exactly what sin is.”

- p.368

- “It may take either of two forms, according as the sinking into sense directly involves only the violation of the spirit's own self-reverence or the graver assault upon the sacredness of others. In either case it is dishonour of God. The risk of it lies in the nature of our being, goes back to the conditions of our existence, of our self-definition in freedom; is constituent in our freedom as this is defined against the freedom of God. This risk is therefore "original" in a sense even deeper than that in which traditional theology makes sin to be original,”

- p.368-9

- “Our sense of alternative is the sense that the transcending view which connects us with our Divine Ideal, and which moves us evermore toward harmony with that, is really ever-living, and so affords resources to reduce our defective difference and carry us beyond all temporal actualities. So that when we halt in any stage of these, and act as if our aim and object ended there, and we were there fulfilled, we know that this is false. We know that we have belied our real being, that in our true nature is a fountain out-measuring every possible actuality, that therefore we might have done differently, and that consequently we have contracted guilt — guilt, not simply before some external tribunal, be it even God's, but guilt before the more inexorable bar of our own soul.”

- p.370-1

- “But now we come upon another objection, which I judge will be the last you can raise. You will say, I suspect, that this world of freedom, self-equipped for sin, is indeed a world which "lieth in wickedness," that in truth there is no real hope of good in it: it is a world of inherent and inexpugnable wrong, and not only damnable, but in fact already damned.”

- p.372

- “The infinite of the soul is mightier than the finite in it.”

- p.373

- “The free-infinite of the intelligence will go on in the conflict of transforming the finitude of the natural life; will go on to victory ever more and more. It may be, as was said before, by paths never so dark and devious, or now and again even retrograde; it may be by descent with the natural into the nether pit of sin and its self-operating punishment; but onward still the undying free spirit goes, and will go, secure in its own indestructible vision of its eternal Ideal, secure in the changeless light shed on it by the changeless God.”

- p.373-4

- “For it is assured of immortality — an immortality that some day, be the time here or be it in the hereafter, must attain to life eternal, to the established dominance of the spiritual over the natural.”

- p.374

- “Freedom and determinism are only the obverse and the reverse of the two-faced fact of rational self-activity. Freedom is the thought-action of the self, defining its specific identity, and determinism means nothing but the definite character which the rational nature of the action involves. Thus freedom, far from disjoining and isolating each self from other selves, especially the Supreme Self, or God, in fact defines the inner life of each, in its determining whole, in harmony with theirs, and so, instead of concealing, opens it to their knowledge — to God, with absolute completeness eternally, in virtue of his perfect vision into all possible emergencies, all possible alternatives; to the others, with an increasing fulness, more or less retarded, but advancing toward completeness as the Rational Ideal guiding each advances in its work of bringing the phenomenal or natural life into accord with it. For our freedom, in its most significant aspect, means just our secure possession, each in virtue of his self-defining act, of this common Ideal, whose intimate nature it is to unite us, not to divide us; to unite us while it preserves us each in his own identity, harmonising each with all by harmonising all with God, but quenching none in any extinguishing Unit. Freedom, in short, means first our self-direction by this eternal Ideal and toward it, and then our power, from this eternal choice, to bring our temporal life into conformity with it, step by step, more and more.”

- p.375-6

Appendix A: The Essays in their Systematic Connexion

[edit]- “This is the establishment, chiefly upon Kant's foundations, of a new idealistic philosophy, in extension and fulfilment of Kant's own, though also taking impulse from the views of Aristotle and of Leibnitz. This new idealism seeks to rehabilitate the moral individual in his proper autonomy by seating him in the eternal world; that is, in the self-active, and therefore absolutely real, or noumenal, order of being. It thus stands opposed (1) to the current Monism, whether of Naturalism (Spencer, Haeckel, etc.) or of Absolute Idealism (Hegel and the Neo-Hegelians), and (2) to the older Monotheism, with its dualism (the eternal Creator, the temporal creation) of literal production out of nothing, by miracle”

- p.383

- “Thus the theme of Personal Idealism — of an eternal world of many rational beings, all self-active, all arbiters of their own destiny and so alike morally responsible, yet, in the vast round of their combinative being, all harmonised by their coexistence with God and their native attracting apprehension of God's nature — grows from one to another of the ascending evidences for it, as the book advances from the first essay to the last.”

- p.387-8

Appendix B: The System in its Ethical Necessity and its Practical Bearings

[edit]- “The evil in the world is the product of the non-divine minds themselves: the natural evil, of their very nature; the moral, the only real evil, of their failure to answer to their reason with their will.”

- p.392

- “That the historic systems of philosophy, not only those which have been directly influenced by the historic systems of religion and theology, but also those which have originated more or less in opposition to these, or in correction of them, are unequal to meeting the conditions essential to the existence of a moral order and to the possibility of a moral life in individuals, will appear plainly upon a brief analysis of their leading conceptions.

- They are every one of them (with the single exception named below) coloured through and through with creationism, — at least tacit, and generally conscious and deliberate, — a term by which, taken literally, I conveniently designate the reference of all realities to a single First Cause, conceived as explaining existence by being their efficient, or originating, or producing Source.”

- p.393

- “This theme of literal creation is so inwrought into the structure of historic thinking, that it will require a long struggle on the part of criticism to get rid of it. Through the influence of the Church and the philosophical schools, it may be said to have become in fact institutional, so that combating it is like fighting organised civilisation itself. Yet one can make the truth clear, that only by the dislodgment of it is the success of the deeper principle possible which is the real soul of civilisation, — I mean the principle of moral life, the life of duty freely followed.”

- p.394

- “On the ground either of positivism or of materialism, ethics can never, properly speaking, be morals. If it escapes fatalism of the hardest sort, with all the consequent hopelessness for most, it cannot avoid hedonism, nor, in the logical end, an egoistic and utterly transient and trivial hedonism.”

- p.395-6

- “A mind heartily moral knows better, when the poet, however plausibly, declares that "whatever is is right." As moral beings, we know that much which is is wrong, and is in no way palliable, or even to be tolerated, by a good being; yes, that our whole business with it is simply to get rid of it, and to bring on a state of the world in which it shall no longer have room to exist.”

- p.398

- “Under such lights as these, which are shed from what the vast majority of thinking men agree is the profoundest and best that is in us, all such systems as we have described display their final moral incompetency. Let us turn now to the new view, the view that abandons both monism and monarchotheism, that abandons creationism in both its forms, takes resort to Final Cause as the primary and only explanatory principle, and holds to an Eternal Pluralism of causal minds, each self-active, though all recognisant of all others, and thus all in their central essence possessed of moral autonomy, the very soul of all really moral being.”

- p.399

- “The hope of the real and lasting improvement of this present world by our moral endeavour. With lack of this, there would be moral discouragement, and the chief use of this life would be merely to find the means of departing out of it; righteousness could only be "in heaven," — in "the hereafter." This added essential to moral effort Personal Idealism supplies, with assurance of hope, in its indivisible union of the eternal and the temporal worlds; a union in which the eternal is the unitary and governing whole, and the temporal the potentially governed part.”

- p.402

- “To him, the one Absolute Conscience, in every moral disaster our conscience turns for assured refuge and certain renewal of moral courage and strength. That is the real act and infallible function of Prayer.”

- p.403

Appendix C: The System vs. The View of the Oxford Essayists

[edit]- “Idealism is constituted by the metaphysical value it sets upon ideals, not by the aesthetic or the ethical, and rather by its method of putting them on the throne of things than by the mere intent to have them there. It is always distinct from mysticism (which at the core is simply emotionalism), and still more so from voluntarism. Its method is, at bottom, to vindicate the human ideals by showing them to be not merely ideals but realities, and to effect this by exhibiting conscious being as the only absolute reality;”

- p.407

Appendix D: Reply to a Review in the New York Tribune

[edit]- “[T]he word "eternal" must by him be taken to stand for what "temporal" does not and cannot stand for; namely, the unchangeable Ground presupposed by the changing temporal; the necessary as against the contingent; the independent as against the dependent; the primary as against the derivative; the self-existent as against that which exists in and through it; the genuine cause, the causa sui, as against that which is after all nothing but effect, however it may be tied, by the causa sui, in an unrupturable chain of antecedent and consequent. Or we may say it means the noumenon as against the phenomenon; or, in fine, the thing in itself as against the thing in other. That is, the relation between the eternal and the temporal is not, and cannot be, only another case of the temporal relation. The relation is just one of pure reason, and is, in fact, sui generis: the eternal does not precede the temporal by date, but only in logic; it is the sine qua non without which the temporal cannot exist, nor is even conceivable. In brief, throughout my book I mean by the "eternal" simply the Real as contrasted with the apparent; the world of self-active causes as contrasted with the world of derivative effects, in so far passive.”

- p.412-3

- “My readers, I fear, have like my reviewer been somewhat misled by looking into my concluding essay for the most important proofs of my main position. But there I am dealing with a problem, or with problems, important and intricate, indeed, but still subordinate to this main one, and only auxiliary to my principal aim.”

- p.416

Appendix E: Reply to Criticisms of Mr. J.M.E. McTaggert

[edit]- “So far from holding God to be finite, I hold, and in the book clearly teach, that all minds are infinite (in the true qualitative sense of the word), and God preeminently so. (See my pp. 330 seq., 363, and 373). Eternity, self-existence, self-activity, freedom, and infinity are to me all interchangeable terms, and are so treated wherever they turn up in the course of the book. My reviewer falls into a non sequitur when he concludes that I make God finite because I make him one of a community of spirits, each absolutely real; not God's finitude, but his definiteness, is what follows from that. This confusion of the definite with the finite is very common, and is the explanation of two tendencies in sceptical thinking — the tendency to deny the personality of God, whose infinity is supposed to mean his utter indefiniteness, and the tendency, in recoil from the former, to assert God's finitude in order to save his personality, which of course must be definite. But the true infinite, as distinguished from the pseudo-infinite, the infinite of quality in contrast to the infinite of quantity, is entirely definite; more definite, indeed, than any finite can be.”

- p.421-2

- “To remove the name of God from the clarified and purified conception of the eternal Ideal Type would be to do violence, inexcusable affront, to the deepest and truest element in the historic religious consciousness. I feel the strongest assurance that my new interpretation of the name of God is the genuine fulfilment of the highest and profoundest prescience in the historic religious life. What offends us in the Spinozistic or other monistic appropriations of the name " God" is the evident absence from their Absolute of all the essential moral qualities. In these it is that true Deity lies, and all God's metaphysical attributes must be keyed up to them; not one of these "natural" attributes dare be construed in any way that conflicts with the eternal moral essence. If they have been so construed historically (as indeed they have), genuine theology requires that the conception of God shall be relieved of these errors, in order that God's nature may stand revealed as it is in its own reality.”

- p.430

The City of God and the True God as its Head (In Royce’s “The Conception of God: a Philosophical Discussion Concerning the Nature of the Divine Idea as a Demonstrable Reality”)

[edit]- “In short, greatly as I admire all that has been said here to-night, gladly and gratefully as I recognise the genuinely philosophic temper and the authentic philosophic place it all most certainly has, I am still moved to say that my honoured colleagues, in this their common underlying conception, have to my mind all "missed the mark and come short of the glory of God." They have not seized nor expressed the complete Ideal of the Reason.”

- p.89

- “In other words, the conception is a philosophical and real account of the nature of an isolated human being, or created spirit, the numerical unit in the created universe, viewed as such a spirit appears in what has well been called its natural aspect; viewed, that is, as the organising subject of a natural-scientific experience, marked by fragmentariness that is forever being tentatively overcome and enwholed, — if I may coin a word to match the excellent German one ergänzt.”

- p.90-1

- “Personal responsibility and its correlate of free reality, or real freedom, are the whole foundation on which our enlightened civilisation stands; and the voice of aspiring and successful man, as he lives and acts in Europe and in America, speaks ever more and more plainly the two magic words of enthusiasm and of stability — Duty and Rights. But these are really the signals of his citizenship in the ideal City of God. By them he proclaims: We are many, though indeed one; there is one nature, in manifold persons; personality alone is the measure, the sufficing establishment, of reality; unconditional reality alone is sufficient to the being of persons; for that alone is sufficient to a Moral Order, since a moral order is possible for none but beings who are mutually responsible, and no beings can be responsible but those who originate their own acts.”

- p.92-3

- “Under the suffocating burden of the old things that should have passed away, the Christian consciousness forgets, at least in part, that all things are become new, and that man is risen from the dead.”

- p.96

- “It is not to the force or validity of the argument that I object, but to the misinterpretation of its scope. It is a clinching dialectical thumbscrew for the torture of agnostics; yes, with reference to them and their very lawful stadium of thinking, it is even a step of value in the struggle of the soul toward a conviction of its really infinite powers and prospects; but I cannot see in it any full proof of the real being of God. Strictly construed, it is, as I have just endeavoured to show, simply the vindication of that active sovereign judgment which is the light of every mind, which organises even the most elementary perceptions, and which goes on in its ceaseless critical work of reorganisation after reorganisation, building all the successive stages of science, and finally mastering those ultimate implications of science that constitute the insights of philosophy.”

- p.111

- “This light within may indeed prove to be the witness of God in my being, but it is not God himself.”

- p.112

- “For life eternal is life germinating in that true and only Inclusive Reason, the supreme consciousness of the reality of the City of God, — the Ideal that seats the central reality of each human being in an eternal circle of Persons, and establishes each as a free citizen in the all-founding, all-governing Realm of Spirits”

- p.113

- “But a second afterthought would follow, and I should ask: What must be the nature of this life dissevered from Nature,—bodiless, void of all sense-perception? What would be left in it except the pure elements of reason, the pure elements of perception, the pure formularies of science, and pure imagination? But what are these, altogether, but the common equipment, not of my mind or of some other individual mind, but of the universal human nature? And what is that universal nature but just the nature of the eternal Cosmic Consciousness? Yes, my personality has vanished; and death, in dissolving the tie to Nature under the alluring prospect of an existence for me wholly self-referred and self-sustaining, has resolved me back into the infinite Vague of the Cosmic Mind, as this might, perchance, be fancied to be in itself, apart from Nature and creation,”

- p.118-9

- “And there will be, and will ever remain, an impassable gulf between the religious consciousness and the logical, unless the logical consciousness reaches up to embrace the religious, and learns to state the absolute Is in terms of the absolute Ought.”

- p.124

- “It was in this attitude of faith as pure fealty to the moral ideal, that Kant left the human spirit at the close of his great labours. It was the only solution left him, after his thesis of the absolute limitation of knowledge to objects of sense. But surely that thesis has a strange sound, coming from the same lips that utter with equal emphasis the lesson of our really having cognitions that are independent of all experience. This is neither the place nor the time to expose the oversight and confusion by which Kant fell into this self-contradiction; I must content myself with saying that the contradiction exists, and that I think the oversight is exactly designable, and entirely avoidable. There is a truth concealed in Kant's thesis of the immutable conjunction of thought and sense, but there is a greater falsehood conveyed by it.”

- p.124-5

Journals

[edit]- Arithmetic is the science of the Evaluation of Functions, Algebra is the science of the Transformation of Functions.

- Journal of Speculative Philosophy, Vol. 5, p. 175. Reported in: Memorabilia mathematica or, The philomath's quotation-book, by Robert Edouard Moritz. Published 1914

- Mathematics is that form of intelligence in which we bring the objects of the phenomenal world under the control of the conception of quantity. [Provisional definition.]

- "The Departments of Mathematics, and their Mutual Relations," Journal of Speculative Philosophy, Vol. 5, p. 164. Reported in Moritz (1914)

- Mathematics is the science of the functional laws and transformations which enable us to convert figured extension and rated motion into number.—Howison, G. H.

- "The Departments of Mathematics, and their Mutual Relations," Journal of Speculative Philosophy, Vol. 5, p. 170. Reported in Moritz (1914)

- And the most depressing sign about [ Josiah Royce's ] thinking is that he seems perfectly aware how this makes no provision either for immortality or for real freedom, and yet he appears to have no uneasiness under it, but to contemplate this ghastly destiny of ours with a complacency even savoring of self-satisfaction.

- Letter to W.T. Harris; Quoted in: James McLachlan, "George Holmes Howison: The Conception of God Debate and the Beginnings of Personal Idealism." The Personalist Forum. Vol. 15, Nr. 1 (1995). p. 6; Cited in Dwayne Tunstall, Yes, But Not Quite: Encountering Josiah Royce's Ethico-Religious Insight, Fordham Univ Press, 2009. p. 12

See Also

[edit]longer version of Howison’s wikiquote

original shorter version Howison's wikiquote

External links

[edit]