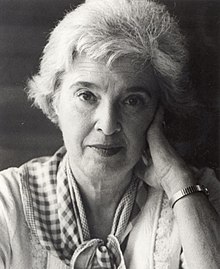

Gerda Lerner

Appearance

Gerda Lerner (30 April 1920 – 2 January 2013) was an Austrian-born American feminist, historian, author, and advocate of Women's History.

Quotes

[edit]- In U.S. historiography, as in American popular culture, historians have tended to over-emphasize the role of the individual in history. Great men are identified as founders and leaders; they become the virtual representatives of the movement: William Lloyd Garrison for abolition, Eugene Debs for the socialist movement, Martin Luther King Jr. for the civil rights movement. In fact, no mass movement of any significance is carried forward by and dependent upon one leader, or one symbol. There are always leaders of subgroups, of local and regional organizations, competing leaders representing differing viewpoints, and, of course, the ground troops of anonymous activists. And, as can be shown in each of the above cases, emphasis on the "great man" omits women, minorities, many of the actual agents of social change. In so doing it gives a partial, an erroneous picture of how social change was actually achieved in the past and thereby fosters apathy and confusion about how social change can be made in the present. As was to be expected, the same distorted historiography would be applied to the nineteenth-century woman suffrage movement. By elevating Stanton and Anthony to the great and unique leaders of the movement; by omitting Lucy Stone and most of the New England activists; by down-playing the role of radicals like Frances Wright, Ernestine Rose, and labor movement activists; and by disregarding the parallel struggles of African American women for suffrage and equal rights the movement's breadth and depth were lost and the complexities of its tactics were obscured.

- Living With History / Making Social Change (2009)

- Men have been writing the history of the world from their point of view, and according to their sets of values, for over 2000 years. In fact, 4000 years, if you want to be strict about it. Because when writing was invented, it was 4000 years ago and ever since then we have history.” I say, “Well, women have begun to reclaim their history about 150 years ago, and the modern women’s history movement is about 35 years old.” I say, “You give us 4000 years, and we’ll mainstream. I think we need to get a perspective that is larger than our time, larger than our memory, larger than our lifetime.

- Patriarchy has not only invented itself and usurped a central place, but it has usurped intellectually, a kind of legitimacy, that described anything that is not like it, as deviant. And men and women have gone into that for 4000 years. Not all women. There were always some women who resisted. And our great tragedy is, that because we were deprived of a history of women, generation after generation of women who wanted to resist patriarchy, had to do it on their own.

- I have documented 700 years of feminist bible criticism prior to 1870, and every woman who engaged in that feminist bible criticism thought she was the first woman ever to do this. And when Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1893, published the Woman’s Bible, she put in the forward, “No woman before me has ever done this.” This is tragic, because it symbolizes the true position that women held in the world, which was to think, each woman thought, and each man taught each woman to think, and each mother taught their sons and daughters to think, that women have not contributed significantly to the creation of thought, to the creation of culture, and to the creation of civilization. This is a lie, all right?

- We are living at a very wonderful moment. A moment that I believe is more important than a renaissance, a moment that is more important than the reformation. It is the moment when half of the human race is reclaiming its ID as full human beings. We have regained our history. And by regaining our history and by transmitting it to the next generation, we will create a basis where women will no longer have to reinvent the wheel. We will be able to stand on the shoulders of the women before us, and I think this is a very wonderful and exciting endeavor.

- I believe myself that appointing women with their history is the single most important thing we can do to raise feminist consciousness. And feminist consciousness means for women to understand that they have a grievance in this world. That the grievance is not individual, that to change their grievance, they need to ally with other women. They need to define for themselves what their goals are. They need then, to form alliances with men and women to attain their goals, and that when their goal is attained, we will have a better society for all of us. Men and women.

Why history matters (1997)

[edit]- In the final analysis, after a lifetime spent as a writer and as a historian, I must take a stand in my own right. History matters to me, for the many and complex reasons that are documented in this volume, and I feel the need to find a proper form for expressing why it does.

"A Weave of Connections"

[edit]- Among equals there is no category of "Otherness." The act of categorizing another implies oppression.

- I have sometimes been asked, "How has your being Jewish influenced your work in Women's History?" The simplest way I can answer this question is, I am a historian because of my Jewish experience.

- What I learned from that comfortable, sheltered life I led in a country in which Catholicism was the state religion and antisemitism was an honored political tradition, was that being Jewish set one apart. Jews were not "normal," we were not right, we were different. And that difference had something to do with our inescapable, compelling history.

- Assimilated Jews did not wish to dwell on the actuality of European Jewish history. There were biblical times and there was the present. What was forgotten and silenced out of existence was the long, bitter, repetitive history of persecution. There was no good news in it. As a child I once heard a story of how in the Middle Ages the Jews of certain German cities had been forced onto leaky boats to float down the Rhine river and drown to the last man, woman and child. Such stories made me feel the shame of belonging to a group so thoroughly victimized. Victims internalize the guilt for their victimization; they become contemptible for being available to victimization. Did they never fight back? Did they go like sheep? Today, I know innumerable instances of Jewish heroism, resistance, fighting back in the series of medieval antisemitic disasters which led to the 15th-century holocaust which destroyed two-thirds of the Jewish communities of western Europe and ended with the expulsion of all Jews from Portugal and Spain. I never heard of this history, not at school, not at home, not in the synagogue, any more than I heard of the existence of a women's history.

- What is left to a Jew who refuses the religious community? Antisemitism and history. In short order I experienced plenty of both.

- After the Holocaust, history for me was no longer something outside myself, which I needed to comprehend and use to illuminate my own life and times. Those of us who survived carried a charge to keep memory alive in order to resist the total destruction of our people. History had become an obligation.

- To be a Jew means to live in history. The history of the Jews is a history of one holocaust after another with short intervals of peaceful assimilation or acculturation. Most of us never study this long and bitter history and yet we live with it and it shapes our lives. We live from pogrom to pogrom, one of my friends recently said. What it means to be a Jew-having to look over your shoulder and have your bags packed.

- Why did I spend years helping to develop the then nonexistent field of Black Women's History and never, until recently, study the history of Jewish women? As one who chose to be an American, I had to accept the problematic in my newly adopted home together with the good. Race was the crucial issue in America. The relative freedom of the American Jewish community compared with Jews in other countries, and its long existence under conditions of tolerance and open access to the resources of the society, is no doubt due to the existence of the American Constitution and its protections, but it is also due to the existence of racially defined minorities which are the primary target for discrimination, hatred and scapegoating.

- The way the system of competing outgroups works, there is an incentive for members of one minority group to display their assimilation, their Americanism as it were, by participating in institutionalized racism. Thus some European Jewish immigrants, who in all their lives had never seen a person of color, learned racism in short order once they assimilated to American society. I wanted to be an American but I did not want to assimilate to the evil of racism, here any more than there. It was logical for me as a scholar to focus on the issue of race in American history and because of my interest in women, on the history of black women.

- In order to survive in this interconnected global village we must learn and learn very quickly to respect others who are different from us and, ultimately, to grant to others the autonomy we demand for ourselves. In short, celebrate difference and banish hatred.

The Creation of Patriarchy (1986)

[edit]- Women's History is indispensable and essential to the emancipation of women.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, Introduction, p. 3

- Women have been kept from contributing to History-making, that is, the ordering and interpretation of the past of humankind. Since this process of meaning-giving is essential to the creation and perpetuation of civilization, we can see at once that women's marginality in this endeavor places us in a unique and segregate position. Women are the majority, yet we are structured into social institutions as though we were a minority.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, Introduction, p. 5

- What women must do, what feminists are now doing is to point to that stage, its sets, its props, its director, and its scriptwriter, as did the child in the fairy tale who discovered that the emperor was naked, and say, the basic inequality between us lies within this framework. And then they must tear it down.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, Introduction, pp. 13-14

- There was a considerable time lag between the subordination of women in patriarchal society and the declassing of the goddesses. As we trace below changes in the position of male and female god figures in the pantheon of the gods in a period of over a thousand years, we should keep in mind that the power of the goddesses and their priestesses in daily life and in popular religion continued in force, even as the supreme goddesses were dethroned. It is remarkable that in societies which had subordinated women economically, educationally, and legally, the spiritual and metaphysical power of goddesses remained active and strong.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 7, pp. 141-142

- There was therefore no inevitability in the emergence of an all male priesthood. The prolonged ideological struggle of the Hebrew tribes against the worship of Canaanite deities and especially the persistence of a cult of the fertility-goddess Asherah must have hardened the emphasis on male cultic leadership and the tendency toward misogyny, which fully emerged only in the post-exilic period. Whatever the causes, the Old Testament male priesthood represented a radical break with millennia of tradition and with the practices of neighboring peoples. This new order under the all-powerful God proclaimed to Hebrews and to all those, who took the Bible as their moral and religious guide that women cannot speak to God.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 8, pp. 178-179

- The consequence of sexual knowledge is to sever female sexuality from procreation. God puts enmity between the snake and the woman (Gen.3:15). In the historical context of the times of the writing of Genesis, the snake was clearly associated with the fertility goddess and symbolically represented her. Thus, by God's command, the free and open sexuality of the fertility-goddess was to be forbidden to fallen woman. The way her sexuality was to find expression was in motherhood. Her sexuality was so defined as to serve her motherly function, and it was limited by two conditions: she was to be subordinate to her husband, and she would bring forth her children in pain.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 9, pp. 196-198

- It should be noted that when we speak of relative improvements in the status of women in a given society, this frequently means only that we are seeing improvements in the degree in which their situation affords them opportunities to exert some leverage within the system of patriarchy. Where women have relatively more economic power, they are able to have somewhat more control over their lives than in societies where they have no economic power. Similarly, the existence of women's groups, associations, or economic networks serves to increase the ability of women to counter act the dictates of their particular patriarchal system. Some anthropologists and historians have called this relative improvement women's "freedom." Such a designation is illusory and unwarranted. Reforms and legal changes, while ameliorating the condition of women and an essential part of the process of emancipating them, will not basically change patriarchy. Such reforms need to be integrated within a vast cultural revolution in order to transform patriarchy and thus abolish it.

- The system of patriarchy can function only with the cooperation of women. This cooperation is secured by a variety of means: gender indoctrination; educational deprivation; the denial to women of knowledge of their history; the dividing of women, one from the other, by defining "respectability" and "deviance" according to women's sexual activities; by restraints and outright coercion; by discrimination in access to economic resources and political power; and by awarding class privileges to conforming women.

- For nearly four thousand years women have shaped their lives and acted under the umbrella of patriarchy, specifically a form of patriarchy best described as paternalistic dominance.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 10, p. 217

- Most significant of all the impediments toward developing group consciousness for women was the absence of a tradition which would reaffirm the independence and autonomy of women at any period in the past. There had never been any woman or group of women who had lived without male protection, as far as most women knew. There had never been any group of persons like them who had done anything significant for themselves. Women had no history—so they were told; so they believed. Thus, ultimately, it was men's hegemony over the symbol system which most decisively disadvantaged women.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 10, p 219

- As long as both men and women regard the subordination of half the human race to the other as "natural," it is impossible to envision a society in which differences do not connote either dominance or subordination. The feminist critique of the patriarchal edifice of knowledge is laying the groundwork for a correct analysis of reality, one which at the very least can distinguish the whole from a part. Women's History, the essential tool in creating feminist consciousness in women, is providing the body of experience against which new theory can be tested and the ground on which women of vision can stand. A feminist world-view will enable women and men to free their minds from patriarchal thought and practice and at last to build a world free of dominance and hierarchy, a world that is truly human.

- The Creation of Patriarchy, ch. 10, pp. 227-229

The majority finds its past (1979)

[edit]- During the interview at Columbia, prior to my admission to the Ph.D. program, I was asked a standard question: Why did I take the study of history? Without hesitating I replied that I wanted to put women into history. No, I corrected myself, not put them up into history, because they are already in it, what I want to do is to make the study of women's history legitimate. I want, I said plainly, to complete the work begun by Mary Beard...In a very real sense I consider Mary Beard, whom I never met, my principal mentor as a historian.

- The essay ("The Lady and the Mill Girl") was in part an outgrowth of my research in ante-bellum reform movements, in part a response to the a-historical analysis of women's place in society in a book like Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique and in some of the early pamphlet literature of the women's liberation movement.

- The number of women mentioned in textbooks of American history remains astonishingly small to this day, as does the number of biographies and monographs by professional historians dealing with women. (1969 article)

- Radical feminism combines the ideology of classical feminism with the class-oppression concept of Marxism, the rhetoric and tactics of the Black Power movement, and the organizational structure of the radical student movement. (1970 article)

"Autobiographical Notes"

[edit]- Even in its surface meaning, the term "Women's History" calls into question the claim to universality which "History" generally assumes as a given. If historial studies, as we traditionally know them, were actually focused on men and women alike, then there would be no need for a separate subject. Men and women built civilization and culture and one would assume that any historical account written about any given period would recognize that basic fact. But traditional history has been written and interpreted by men in an androcentric frame of reference; it might quite properly be described as the history of men. The very term "Women's History" calls attention to the fact that something is missing from historical scholarship and it aims to document and reinterpret that which is missing. Seen in that light, Women's History is simply "the history of women."

- Women's History is a stance which demands that women be included in whatever topic is under discussion. It is an angle of vision which permits us to see that women live and have lived in a world defined by men and most frequently dominated by men and yet have shaped and influenced that world and all human events.

- I came into the study of history through my work on a biography of Sarah and Angelina Grimké... I was fascinated with the lives and characters of these two women, who had not had a biography written about them since 1885... They spoke to me in a very personal way and I wanted to transmit what I received from these women of another century to readers of my day.

- What I was learning in graduate school did not so much leave out continents and their people as it left out half the human race, women.

- Revisionist theories usually begin with an argument with one's predecessors. In my case, these predecessors were 19th- and 20th-century feminist writers, who saw women's history as a manifestation of women's oppression and focused excessively on the struggle for women's rights. The most recent, and certainly indispensable book was Eleanor Flexner's Century of Struggle, which cut a wide swath, although it was essentially written in the woman's rights framework.

- As I began to work on my research priorities, the absence of black women from history appeared to me as an urgent problem to be considered.

- Feminist consciousness begins with self-consciousness, an awareness of our separate needs as women; then comes the awareness of female collectivity-the reaching out toward other women, first for mutual support and then to improve our condition. Out of the recognition of communality, there emerges feminist group consciousness a set of ideas by which women autonomously define ourselves in a male-dominated world and seek to substitute our vision and values for those of the patriarchy. The two aspects of my own consciousness, that of the citizen and that of the woman scholar, had finally fused: I am a feminist scholar.

Quotes about Gerda Lerner

[edit]- She is one of the most prominent historians in our country...I first remember Gerda when we founded the first NOW chapter in the country, which was New York NOW – we’re all proud of that – in March 1967. I passed out a yellow line pad for people to write down their biographies, and Gerda Learner was in the room. She wrote down that she was teaching at Sarah Laurence, she was interested in women’s history. Gerda used to come to those early NOW meetings. I remember one day she said to me, “Would you please mention to the people in this chapter that I am writing this history on the Grimke Sisters and it’s going to come out soon?” And that was our first feminist history that really came out of NOW. Not the last, but the first, and we were all very proud of her.

- Muriel Fox Speech (1998)

- A pioneering historian of women

- Nell Irvin Painter The History of White People (2010)

- The new historians of "family and childhood," like the majority of theorists on childrearing, pediatricians, psychiatrists, are male. In their work, the question of motherhood as an institution or as an idea in the heads of grown-up male children is raised only where "styles" of mothering are discussed and criticized. Female sources are rarely cited (yet these sources exist, as the feminist historians are showing); there are virtually no primary sources from women-as-mothers; and all this is presented as objective scholarship. It is only recently that feminist scholars such as Gerda Lerner, Joan Kelly, and Carroll Smith-Rosenberg have begun to suggest that, in Lerner's words: "the key to understanding women's history is in accepting-painful though it may be-that it is the history of the majority of mankind.... History, as written and perceived up to now, is the history of a minority, who may well turn out to be the 'subgroup.'"

- Adrienne Rich. forward to Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution

External links

[edit]Categories:

- Academics from the United States

- Academics from Austria

- Feminists from the United States

- Humanists

- Marxists from the United States

- Essayists from the United States

- Essayists from Austria

- Historians from the United States

- Historians from Austria

- Educators from the United States

- Educators from Austria

- Autobiographers from the United States

- Jews from Austria

- Jews from the United States

- Immigrants to the United States

- People from Vienna

- 1920 births

- 2013 deaths

- Women authors

- Women from the United States

- Women born in the 1920s