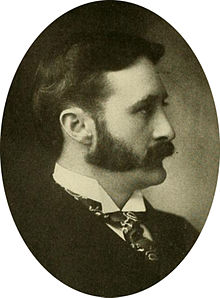

Harry Gordon Selfridge

Appearance

circa 1910

Harry Gordon Selfridge (January 11, 1858–May 8, 1947) was an American-British retail magnate who founded the London-based department store Selfridges after retiring as Marshall Field's partner, opening and selling Harry G. Selfridge and Co. in Chicago in only 2 months, and moving to England. His 20-year leadership of Selfridges led to his becoming one of the most respected and wealthy retail magnates in the United Kingdom. He was known as the 'Earl of Oxford Street'.

Quotes

[edit]- The boss drives his men; the leader coaches them.

The boss depends upon authority; the leader on goodwill.

The boss inspires fear; the leader inspires enthusiasm.

The boss says 'I'; the leader, 'We'.

The boss fixes the blame for the breakdown; the leader fixes the breakdown.

The boss knows how it is done; the leader shows how.

The boss says 'Go'; the leader says 'Let's go.'- As quoted by Elmer Wheeler, Tested Sentences that Sell (1937) citing B. C. Forbes.

- People will sit up and take notice of you if you will sit up and take notice of what makes them sit up and take notice.

- As quoted by Simon Cooper, Brilliant Leader 2e: What the best leaders know, do and say (2013)

- Right or wrong, the customer is always right.

- As quoted by Jeff Toister, Service Failure: The Real Reasons Employees Struggle with Customer Service and what You Can Do about it (2012) This quote has also been attributed to Selfridge's business associate, Marshall Field. The previous prevailing motto in the field was "Assume that the customer is right until it is plain beyond all question he is not."

The Romance of Commerce (1918)

[edit]

circa 1880

- To the Merchants and Men of Commerce throughout the entire world, or to those among them who love their calling and count themselves fortunate in being able to follow its intricate but fascinating paths—to those who look upon work as glorious and to be sought—who look upon idleness as unproductive and to be avoided—to those whose efforts are unitedly making the world busier, happier, richer, and more able to provide the good things of life, this volume is dedicated by The Author.

- Book Dedication

Concerning Commerce

[edit]- Chapter I

- To write on Commerce or Trade and do the subject justice would require more volumes than any library could hold, and involve more detail than any mind could grasp. It would be a history in extenso of the world's people from the beginning of time. For we are all merchants, and all races of men have been merchants in some form or another.

- The desire to trade seems to be inherent in man, as natural to him as the instinct of self-preservation, and from earliest recorded history we see trade and barter entering into and becoming part of the lives of men of all nations... [W]e see it as one of the most desirable objectives of the nations themselves.

- Ever since that moment when two individuals first lived upon this earth, one has had what the other wanted, and has been willing for a consideration to part with his possession. This is the principle underlying all trade however primitive, and all men, except the idlers, are merchants.

- [T]he artist sells the work of his brush and in this he is a merchant. The writer sells to any who will buy, let his ideas be what they will. The teacher sells his knowledge of books—often in too low a market—to those who would have this knowledge passed on to the young.

The doctor... too is a merchant. His stock-in-trade is his intimate knowledge of the physical man and his skill to prevent or remove disabilities. ...The lawyer sometimes knows the laws of the land and sometimes does not, but he sells his legal language, often accompanied by common sense, to the multitude who have not yet learned that a contentious nature may squander quite as successfully as the spendthrift. The statesman sells his knowledge of men and affairs, and the spoken or written exposition of his principles of Government; and he receives in return the satisfaction of doing what he can for his nation, and occasionally wins as well a niche in its temple of fame.

The man possessing many lands, he especially would be a merchant... and sell, but his is a merchandise which too often nowadays waits in vain for the buyer. The preacher, the lecturer, the actor, the estate agent, the farmer, the employé, all, all are merchants, all have something to dispose of at a profit to themselves, and the dignity of the business is decided by the manner in which they conduct the sale.

- [W]ithout Commerce there is no wealth.

- Commerce creates wealth, and it is the foundation of the great state. Armies are raised and paid for to win, or to protect the countries' trade, or commerce. Ships are constructed, colonies established, inventions encouraged, governments built up, or pulled down, for Commerce. Commerce cuts the way, and all professions, all arts follow.

- If Commerce is necessary to wealth, no Commerce means no wealth, and our statesman soon finds himself out of employment. Where wealth again is greatest, everything else being fairly equal, arts thrive the most.

- A thousand departments of mental and physical activity foster and in turn are fostered by its achievement. People must be governed, and there must be those who govern. Laws must be made, and there must be those who study, and those who execute these laws. People must be taught, and there must be teachers. All these and the Church, the newspaper, the theatre, the fine arts are essential to the completeness of the State, to the happiness and safety of its people; but Commerce is the main stem, or trunk, where they are all branches, supplied with the sap of its far-reaching wealth. It is as necessary to the existence of any nation as blood to the physical man. That country in which trade flourishes is accounted happy, while that in which Commerce droops provokes shaking of heads and prophecies of downfall.

- Commerce is the mother of the arts, the sciences, the professions, and in this twentieth century has itself become an art, a science, a profession.

A Representative Business of the Twentieth Century

[edit]- Chapter XXIV

Vanity Fair, Jun 6, 1911

- One of the chief differences between the commerce of the sixteenth century and of the twentieth lies in the wonderful and complicated organizations of the present day. Their magnitude makes even the largest of those of which we have been reading seem insignificant.

- The Phoenicians a thousand years before the Christian era were fearless, progressive and splendid, but... [t]hey traded individually as did the Venetians and even the great Fuggers of Augsburg, leaving no trace of that ability which selects and teaches others to assist in any remarkable enterprise.

- Where one Jacob Fugger, Cosimo de Medici, de la Pole or Gresham strove for success we have now literally thousands of keen, clever men as fearless, as progressive and as determined as they. Money not only for the few but for the many is the prize which is sought, and for this prize is the race now perhaps swifter, the battle keener, the game bigger than has been any race, battle, or game since the world began; and commerce in its broader sense is the medium through which this prize is won.

- And the day of physical adventure is over. The day of the bold Phoenician, the fearless trader who with his caravan threaded his way into unknown lands; the day when the early English merchant-sailor trusted and risked his fortune in one small boat, and sought out markets and trading points in undiscovered corners of the earth—these days are gone for ever. The earth has all been "discovered," its lands and peoples are known, and its oceans charted. The merchant who desires to transact business abroad has at his call every detail of information regarding every country, island, or people.

- The world is smaller. Steam and electricity, great ships, railways and many recorded experiences have made it so; but as the circumference of this earth has seemed to diminish its commercial undertakings have grown greater.

- Men of genius and wonderful nerve and determination, who in the Dark Ages would have been conquering princes, have... thrown their ability into Commerce and have conquered, not territory and slaves, but trade and its child, money, from any and every part of the world where trade was to be found.

- The last hundred years have shown... that one man cannot do it all, and that anyone who attempts to hold within his two hands all the threads of a great business of the present day fails to achieve the greatest success.

- No one has more than a given number of minutes... in which he can work, and no matter how great his ability he will soon find his limitations. If, however, he uses that ability in finding and teaching others as capable as himself, or in certain details even more so, the limits to his sphere of operations are hard to set.

- This ability... to organize, to breathe into others that fire of enthusiasm, that quality of judgment, that spirit of progress, has long been considered by thinking men of commerce as the final and greatest of all qualities, the test of supreme commercial genius.

- [T]he great Distributing House or Department Store... may be permitted to represent the modern spirit of organization. It is to the writer the most interesting of all forms of business, and by its constant and necessary publicity it occupies perhaps the most conspicuous place in the public mind. It usually employs the greatest number of people... It frequently... pays out in salaries and wages a larger sum weekly than any other single business, and is more often approached by those seeking opportunity to work than any other. Its daily transactions are large in volume, its cash handled is very great. It is intimately associated with every family in the community in supplying them with the necessities of life, and thus... enters into the daily life of the city in which it is.

- [A] hundred years ago the selling of goods at retail had settled into a system of small shops, each confining itself to a particular class of merchandise. The comprehensive trade of the sixteenth century had been divided into small sections, and the smaller the section the smaller was the study, the amount of experience and the capital required. The retail trade of shop-keeping became in consequence a petty and insignificant undertaking, necessitating little risk, little profit, and little ability, and so generally was this fact accepted that the name of shop-keeper became a term of reproach and of disrespect.

- In all parts of the world this condition existed till about half a century ago, when a few shop-keepers became inoculated with the spirit of enterprise. They grew beyond the little shop by the simple process of addition... Then it was that department stores in their early stages began to appear, and... they have continued to develop in every direction, and no man can foresee their final form and size, or say where they will stop. No one who knows the ramifications of these great modern stores can feel for a moment that they have reached their highest point of achievement. The room for improvement is still the biggest room in the world, and all that is now done means a step forward into a new and hitherto undreamed of realm, and to this much of the excitement and interest of such a business is due.

- Imagination must be drawn upon, risks must be assumed. "Nothing venture, nothing have" is perhaps truer of the department store than of any other enterprise.

- In France the height of the structures is limited to five or six storeys: in America stores frequently tower up fifteen storeys or more, and with rapid smooth-running lifts one floor is as good as another. These buildings measure their floor area by the acre, and twenty, thirty, or even forty acres of floor space—or even two million square feet—are not extraordinary, while it is quite likely that before the ink on these pages has become dry some great merchant with imagination, courage and ambition will announce his purpose of erecting a structure perhaps twice as large as any now in existence. If he does so it will not be for the sake of having the biggest thing on earth but because more space will allow him to set the word "perfection" further out in the hitherto unexplored fields of endeavour.

- Bigness alone is nothing, but bigness filled with the activity that does everything continually better means much.

- The floors are of marble or mosaic or are covered with hundreds of thousands of yards of carpets. The lifts are almost without number...

- The merchant sends the buyer far afield with instructions to invest... in... staples or novelties, as he thinks will interest the home public. He risks his money and a certain amount of prestige upon the judgment of the buyer... Much merchandise begins to depreciate from the day it arrives; practically none increases in value. The buyer then must learn to buy enough and not too much; to buy what will give satisfaction..; to pay not too much for what he buys; to know qualities and values... All this carries with it a certain speculative risk, but so certain does his judgment become, that the house conducted on scientific lines can estimate to a fraction of one per cent.

Quotes about Selfridge

[edit]

Warehouse Store

circa 1910

- No one knew or would say just how wealthy he was. He made an estimated fortune of $1,500,000 after retiring as Marshall Field's partner in 1904. He made another fortune by upsetting hidebound British tradition in retailing merchandise. But the family spokesman says he was "not a wealthy man" when he died... He raised wages and treated employees as co-workers rather than servants. ...[P]eople flocked to his store ...He became a British subject in 1937 and retired from business in 1940 for a second time, but stayed on as an $8,000 a year consultant to the Gordon Selfridge Trust, to which he had sold all his store holdings. His last visit to Ripon was in 1939, when he stayed at the home of Dr. Silas Evans, president of Ripon College. In 1935 he had received an honorary degree from the college. ...He first studied for the Naval Academy at Annapolis... [b]ut he was a quarter of an inch too short, and went to work for Field's instead.

- "Selfrige Dies; Ripon Lad Who Jolted Empire - Forced U.S. Methods Upon British" (May 9, 1947) Milwaukee Sentinel, Part 1, p. 5.

- Harry Gordon Selfridge... started with the firm in 1879. ...[H]e began as a ten-dollar-a-week stock boy. ...Selfridge was exuberant, dramatic and hurried. He soon gained the nickname "mile-a-minute Harry" for his breathless speech and rapid gait. He was quickly promoted to salesman... Selfridge immediately locked horns with the retail superintendent... Selfridge considered Fleming a rusty old dinosaur who was preventing retail from growth. When Fleming sniffed in disdain at one of his many ideas, he would simply march to Field's office and plead his case. ...Field ...saw a man of vision and an unerring instinct for what the customer wanted. ...Soon, Selfridge was promoted to run the entire retail division. In 1889... Selfridge ...requested a partnership interest. Field was stunned... in 1889, Selfridge was awarded a 2/85th share, with Field loaning him the $200,000 in required capital.

- Gayle Soucek, Marshall Field's: The Store that Helped Build Chicago (2010)

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- The Romance of Commerce (1918) by Harry Gordon Selfridge @GoogleBooks

- The Romance of Commerce by Harry Gordon Selfridge @Internet Archive

- Biography from the DNB