Kanan Makiya

Appearance

Kanan Makiya (born 1949) is an Iraqi-American academic and a professor of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at Brandeis University.

Quotes

[edit]

1990s

[edit]- Millions upon millions of words have been written about the destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages in order to bring about the creation of the Israeli state. And rightly so. Yet many of the very intellectuals who wrote those words chose silence when it came to the elimination of thousands of Kurdish villages by an Arab state.

- As quoted in "The Dissident" (3 November 2002), by Laura Secor, The Boston Globe, Massachusetts: Globe Newspaper Company, p. D1

2000s

[edit]- I think there's a less than 5 percent chance that what I'd like to see happen actually happens. But it seems to me an obligation, even if it’s a 5 percent chance, to try to make it happen. You could call it a triumph of hope over experience. But what else is politics if not that?

- As quoted in "The Dissident" (3 November 2002), by Laura Secor, The Boston Globe, Massachusetts: Globe Newspaper Company, p. D1

- [Saddam Hussein's execution] was a disaster, an unmitigated disaster. I was just so upset, even on the verge of tears. It was the antithesis of everything I had been working for and hoping for.

- As quoted in "Critic of Hussein Grapples with Horrors of Post Invasion Iraq" (25 March 2007), by Edward Wong, The New York Times

- Someone has to keep dreaming.

- As quoted in "Critic of Hussein Grapples with Horrors of Post Invasion Iraq" (25 March 2007), by Edward Wong, The New York Times

- People say to me, "Kanan, this is ridiculous, democracy in Iraq, a complete pipe dream," ... That's realism. You know, in a way, the realists are right, they are always right. Even when they are morally wrong.

- As quoted in "Regrets Only?" (7 October 2007), by Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Magazine

- I want to look into myself, look at myself, delve into the assumptions I had before the war.

- As quoted in "Regrets Only?" (7 October 2007), by Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Magazine

- I ran into a whole number of people for whom bodies did not count. You know: the historical process, the victory for the working class. The great big idea that could take place at the expense of any number of bodies because ultimately, in the very, very long run, lives would be saved. I would not make that argument anymore. It is utterly repugnant to me.

- As quoted in "Regrets Only?" (7 October 2007), by Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Magazine

- Nothing was inevitable. People made choices. Everything was in flux. It could have gone so many different ways. The real tragedy that we are facing now is why Iraqis are not making the right choices, why we are missing all the opportunities.

- As quoted in "Regrets Only?" (7 October 2007), by Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Magazine

Faith and Doubt at Ground Zero (2002)

[edit]- "Faith and Doubt at Ground Zero" (2002), PBS Frontline

- Evil is something that, when you see it, when you know it, it's intimate. It's almost sensual. That is why people who have been tortured know it by instinct. They don't need to be told what it is, and they may have a very hard time putting it into words. ... That's the nature of the phenomenon. It's hard to put into words.

- Suggesting evil is human doesn't mean we can always understand it, or doesn't mean there's only one way of understanding it. It's sort of like a great work of art. You can never fully absorb it. It's got many dimensions. It lives on through time, in different ways.

- I have always thought there were dark ... corners in religion. I took that for granted. That's not the surprising thing for me. ... The frightening thing is rather that, in the Arab world, we have let the darkness of religion flourish.

- Perhaps the most dangerous element that was picked out of the Muslim tradition and changed and transformed in the hands of these young men who perpetrated Sept. 11 is this idea of committing suicide. They call it martyrdom, of course. Suicide is firmly rejected in Islam as an act of worship. In the tradition, generally, to die in battle for a larger purpose -- that is, for the sake of the community at large -- is a noble thing to do. Self-sacrifice yourself as you defend the community -- that is a traditional thing, and that has a traditional meaning of "jihad." But what is non-traditional, what is new is this idea that jihad is almost like an act of private worship. You become closer to God by blowing yourself up in such a way. You, privately, irrespective of what effect it has on everyone else. ... For these young men, that is the new idea of jihad. This idea of jihad allows you to lose all the old distinctions between combatants and non-combatants, between just and unjust wars, between the rules of engagement of different types. All of that is gone, because now the act of martyrdom is an act of worship ... in and of itself. It's like going on the pilgrimage. It's like paying your alms, which every Muslim has to do. It's like praying in the direction of Mecca, and so on and so forth. It is an individual act of worship. That's terrifying, and that's new. That's an entirely new idea, which these young men have taken out, developed.

- The Western societies have had hundreds of years of reformation behind them. Islam has never had its reformation, and that is part of the problem. If you look back to the 16th and 17th centuries when men were killing one another in the name of religion throughout Europe, that's where we're at more or less, historically speaking, in terms of the level of debate and discourse. The Quran is considered an untouchable text, not a historical document. ... This is the literal word of God, and it is very dangerous to play with that in the Middle East today.

- The Saudi government has been pumping money in a quiet kind of revolution to shape Islam in its own images since 1973, [with] oil price rises. It wasn't a noisy revolution like the Iranian revolution was. It didn't have so much hubbub and noise associated with it and all. But it was quietly done [with] Saudi influence, using money, and the building of [madrassas] -- that is, religious schools and mosques all across the world. ... The very particular kind of Islam associated with Saudi Arabia ... is an upstart. It was created in the 18th century. It was constrained and confined entirely to the Arabian Peninsula right through to the late 1960s. All of a sudden, this [Wahhabi] Islam -- which is espoused by these young men, which considers even a Muslim like myself, because of my Shiite background, to be dirty or not a real Muslim ... [is] probably the dominant form [of Islam] in the United States. It spreads from one end of the world to the next. It's been a quiet, silent revolution that's been happening, and suddenly exploded on the scene with Sept. 11.

- The defensiveness of Islam is its crucial feature today. It's what, by the way, is in such contrast to the most interesting period of Islamic history, when Islam was an open, absorbing religion, constantly taking in outside influences, as opposed to its current hedgehog-like posture, prickly to the outside ... always looking backward. This is not how it was in the creative moment, in the first four, six, eight centuries of Islam, where it was constantly seeking out and absorbing.

- Bin Laden's real audience is the Middle East, his other Muslims. I think he thought that, by this act, he would win large numbers of converts to his cause ... [to] bring Arab regimes down. He would perhaps even take power in this or that country, preferably Saudi Arabia. That is where he is looking to; that is who is the audience. That is who his symbols are directed towards. So this is unlike anything else in the history of Islam. Early Muslims, when they left the Arabian Peninsula and entered the [Fertile Crescent], were conquerors. They converted peoples, and they gave them time to convert. So they didn't force them sometimes, and they were perfectly happy ruling over them. They were setting up a state, and then people converted over time. Syria remained Christian for hundreds of years after the Muslim conquest. So something different is going on here. The obvious sense in which the United States is evil is in the cultural icons that are seen everywhere. They are seemingly trivial things, the influence of the America culture, which is everywhere: TV, how women dress, the lack of importance of religion. So these are the senses in which they are rejecting the United States. But you're right; they don't see Americans as people. ... They block that out. They only see as people the Muslims they want to convert to their side, and that's terrifying.

- I find it very significant that no religious traditions, Islam included, is ever in a position, I think almost by definition, to put cruelty first in the order of its priorities of the terrible things that human beings can do. That is perfectly illustrated in the story of Abraham's sacrifice with his son. Because, of course, what the story's all about is faith, the importance, and the primacy of faith. ... What is the essence of faith in the story is Abraham's willingness (a) not to question God about his command to sacrifice his son, and (b) to proceed slowly, deliberately, over a period of time -- three days, I think it was -- [and] march up the mountain, prepare the sacrifice, unquestioning, resolute. [It was] the perfect, as Kierkegaard put it, "night of faith" model, exemplar of faith. And [Abraham] is, in the Muslim tradition exactly that -- an exemplar of faith. That is the importance of Abraham to Muslims. ... Had he faltered, his faith would have been less, a degree or so less. He didn't falter. God immediately stops it at the absolute last moment and, of course, the act is ended. But what the story is all about is how faith in God comes first, before anything else, and then follow various virtues, of which harm to other human beings surely has to be below faith. It seemed to me that that is something that the hijackers certainly took to heart.

- The Muslim idea of God is, in many ways, more abstract, more remote and less human, certainly, than the Christian and the God of the Old Testament, who has passions and has angers and often behaves very much like a human being in the various stories. The Muslim is more remote, aloof, distant, and has to be obeyed. He has many, many different facets.

- What makes people enter into cults? I think that kind of certainty about something is not necessarily just religious. It was seen in secular organizations, secular ideologues, ideological organizations of one kind or another. I've experienced it among people I used to know in the 1960s and 1970s. It's a terrifying thing when you see it at work.

A Model for Post-Saddam Iraq (October 2002)

[edit]- "A Model for Post-Saddam Iraq" (3 October 2002), American Enterprise Institute

- ...I would suggest that the removal of the regime of Saddam Husain presents the US with a historic opportunity that is as large as anything that has happened in the Middle East since the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the entry of British troops into Iraq in 1917. Iraq is not Afghanistan. It is rich enough and developed enough and has the human resources to become as great a force for democracy and economic reconstruction in the Arab and Muslim world as it has been a force for autocracy and destruction. But for the world to be able to see the challenge in this way, it is necessary to change the terms of the debate over this coming war with Iraq.

Iraqis Must Share in Their Liberation (March 2003)

[edit]- "Iraqis Must Share in Their Liberation" (30 March 2003), The Washington Post

- One cannot liberate a people -- much less facilitate the emergence of a democracy -- without empowering the people being liberated. It is much easier for an Iraqi soldier to join other Iraqis in rebellion than it is to surrender his arms in humiliation to a foreigner who is unable even to communicate with him. And the more that Iraqis help, the less that coalition soldiers will have to engage in house-to-house fighting in cities. It is both morally right and politically liberating for Iraqis to participate and share in their own liberation. They are willing to give their lives for this cause. Their participation is indispensable as it will add legitimacy -- and therefore stability -- to an Iraqi interim authority that otherwise, no matter how you look at it, would be chosen by American officials.

Thank You, America (April 2003)

[edit]- "Thank you, America" (15 April 2003), New York Post

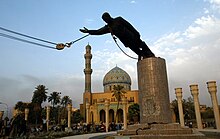

- Ba'athism died in Iraq last week. The sight of the oversized bronze head of Saddam rolling in the dust and being beaten with shoes by exuberant Iraqis is perhaps the most important image of Iraqi politics of the last 50 years. It was the end of the republic of fear. Two Iraqis with whom I was camping out in Washington, D.C., woke me up at 5 a.m. that day so we could watch the images of a free Iraq. Tears rolled down our cheeks uncontrollably.

- Freedom is a heady thing. To an Iraqi, it is like being awakened from a 30-year nightmare by a blinding blaze of bright white light. When a young man steals a television set from the Ministry of Education, he thinks he is striking a blow against the Ba'ath Party. He has not yet become aware that he is in fact stealing it from a building that now belongs to him and is about to start serving his needs, and not those of his tormentors.

2010s

[edit]Intervention in Syria is a Moral and Human Imperative (2012)

[edit]- "Intervention In Syria is a Moral and Human Imperative" (24 February 2012), The New Republican

- I don’t really think there is any kind of a reasonable argument against intervention in Syria. Quite the opposite: There is a moral and a human imperative to act that is larger than any nation’s interests and larger than any strategic calculation. That is so obvious it is an embarrassment to have to say it. This is how I thought about intervention in Iraq 20 years ago and it is how I think about what needs to be done in Syria today.

- ... Assad’s survival—if Saddam Hussein’s murderous rampage in 1991 is any indication—will without a shadow of a doubt translate into hundreds of thousands of Syrian dead, mostly butchered after his victory has been assured. The comparison comes to mind because the two Ba’thi regimes of Saddam Hussein and Bashar Assad bear an unmistakable resemblance—they are mirror images of one another, one might say. Both are minority dominated, single party regimes originating in the same quasi-fascist pan-Arab ideology built on the principle that any form of disagreement is an act of “betrayal” to the “revolution.”

- Washington is right to be chastened after its scathing experience in Iraq this past decade. But it also ought to be motivated by that earlier disaster in Iraq, in which so many innocent Iraqis perished while the United States stood by and watched. Syria in 2012 is another Iraq of 1991 just waiting to happen. No one can say he did not know.

The Arab Spring Started in Iraq (2013)

[edit]- "The Arab Spring Started in Iraq" (6 April 2013), The New York Times

- The removal of Saddam Hussein and the toppling of a whole succession of other Arab dictators in 2011 were closely connected - a fact that has been overlooked largely because of the hostility that the Iraq war engendered.

- No Arab Spring protester, however much he or she might identify with the plight of the Palestinians or decry the cruel policies of Israeli occupation (as I do), would think today to attribute all the ills of Arab polities to empty abstractions like "imperialism" and "Zionism". They understand in their bones that those phrases were tools of a language designed to prop up nasty regimes and distract people like them from the struggle for a better life.

- Generations of Arabs have paid with their lives and their futures because of a set of illusions that had nothing to do with Israel; these illusions come from deep within the world that we Arabs have constructed for ourselves, a world built upon denial, bombast and imagined past glories, ideas that have since been exposed as bankrupt and dangerous to the future of young Arab men and women who set out in 2011, against all odds, to build a new order.

- Mr. Hussein used sectarianism and nationalism as tools against his internal enemies when he was weak. Today's Iraqi Shiite parties are doing worse: they are legitimizing their rule on a sectarian basis. The idea of Iraq as a multiethnic country is being abandoned, and the same dynamic is at work in Syria.

Quotes about Makiya

[edit]- Kanan will always come down for taking a risk for freedom, for liberation, for emancipation because I think he basically thinks that people are decent and good.

- Ali Allawi, as quoted in "Regrets Only?" (7 October 2007), by Dexter Filkins, The New York Times Magazine

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Kanan Makiya on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Kanan Makiya on Wikipedia