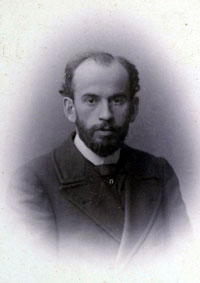

Lev Lvovich Tolstoy

Appearance

Count Lev Lvovich Tolstoy (1 June 1869 – 18 October 1945) was a Russian writer, and the fourth son of Leo Tolstoy.

Quotes

[edit]The Truth about My Father

[edit]- London: John Murray, 1924.

- We had in the Tolstoi family a special dance, which everybody danced with joy when wearisome visitors at last drove off from the house. This was known as the Numidian dance, and it had something African and very wild about it. My father, who was generally the first to lead off, at such times sprang forward, the right hand raised above his head, and began to hop, skip and run around the long table. My mother, in her turn, followed by our tutors, governesses and all the children, launched themselves at the same movement round the table, and when it had been frantically circled several times, everybody stopped, satisfied, and sighed with relief.

- pp. 33–34

- Schopenhauer's ideas on women, on pain, and on freedom of conscience were always completely shared by my father. "When one suffers," said Schopenhauer, "one has the consolation of knowing that the sufferings of others may be greater than one's own." Tolstoi loved to repeat this thought, though I must confess that for me it meant nothing. To my mind, on the contrary, one may suffer still more when one has the knowledge that others are suffering also.

- p. 41

- My mother was the source of Tolstoi's greatest happiness, and the real author of his greatness. If there is sometimes ground for thinking, while reading the works of Tolstoi, "Do what I do, and not what I say!" such things can never be said in reading the book of my mother's life, for she was not only a model and devoted wife, a tender and affectionate mother to her children, a born housekeeper, a woman of society and an author's wife, but she was also the celebrated Russian writer's greatest moral support, without which he would never have attained the position he holds in the eyes of the world today.

- p. 65

- In France it is often said that Tolstoi was the first and great cause of the Russian Revolution, and there is a good deal of truth in this. Nobody has done more destructive work in any country than Tolstoi. The peasant, the soldier, the public official, the nobleman, the priest, and the workman were all reached by the arrows of his accusing mind. There was nobody in the whole nation, in fact, who did not feel himself guilty, from the point of view of the severe condemnation of the great writer.

- p. 100

- Those who have read this book [War and Peace] will remember how the great heart of the author sought, even in the past of his people, the eternal secret of love. In Anna Karenina we find, already distinctly set forth in the personality of Levine, the aspirations of Tolstoi himself, which become more and more conscious and defined. The criticism of modern society, and all its institutions, its science and its literature; the tendency towards the simple and natural life of the people, original and novel ideas in regard to religion—all this is beginning, in the book in question, to take in the heart and brain of the writer a more or less precise form.

- pp. 171–172

- In what did Tolstoi's work actually consist? It is the outcry of the universal conscience. His works voice the consciences of us all, expressed sincerely by the most ardent and the most sensitive of hearts. The popularity of Tolstoi throughout the world is explained solely by the simplicity and the sincerity of his doctrine, which appeals to all, without distinction, calling on mankind to recognise the same great truth, to make the same great moral effort for the realisation of love.

- p. 219