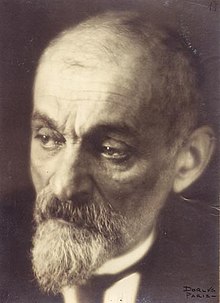

Lev Shestov

Appearance

Lev Isaakovich Shestov (born Yehuda Leib Shvartsman; February 12 [O.S. January 31] 1866 - November 19, 1938) was a Russian existentialist philosopher, known for his "philosophy of despair".

Quotes

[edit]In Job's Balances: on the sources of the eternal truths

[edit]- In Job's Balances: on the sources of the eternal truths 1929 by Shestov, Lev, 1866-1938 Translated by Camilla Coventry and C. A. Macartney Publication date 1975

- Thales was the father of ancient philosophy. His consternation, and the firm beliefs to which this gave rise, were transmitted to his pupils and to their pupils again. The law of heredity exercises as despotic and unlimited a sway in philosophy as in all other fields of organic existence. Let any one who doubts this cast a glance at any text-book. Since Hegel no one has dared imagine that the philosopher is able to think and inquire “freely”. The philosopher grows out of the past, like a plant out of the earth. Foreword xxxi

- Spinoza’s formula, “Deus=natura=substantia”, like all conclusions drawn from it in his Ethics and his earlier works, simply means that there is no God. This discovery of Spinoza’s became the starting point for modern philosophical thought. Foreword p. xxxix

- One of the outstanding examples of the unfree character of modern philosophical thought is perhaps the famous dispute between Hume and Kant. Kant often declared that Hume had awakened him out of “dogmatic slumber.” And in fact, when we read Hume and those passages of Kant in which he appeals to Hume, we might think that this could not be otherwise, and that what Hume saw and what was visible to Kant also, after Hume, must have awakened not only a sleeper, but even a dead man. Foreword p. xlv

The Conquest of the Self-Evident; Dostoievsky’s Philosophy

[edit]- What can be more terrible than not to know whether one is alive or dead? “Justice” should insist that this knowledge or this ignorance should be the prerogative of every human being. p. 3

- Suppose Euripides is right, and that indeed no one can be sure whether life is not death and death life; can this truth ever become certain? If all men daily repeated Euripides’ words when they got up and when they went to bed, they would remain as strange and as problematic as on the day when the poet first heard them in the depths of his soul. P. 6

- There are no ideals exalting the soul, but only chains, invisible indeed, but binding man more securely than iron. And no act of heroism, no “good work” can open the doors to man’s “perpetual confinement”. Dostoievsky’s barrack vows of “improvement” now appeared to him as a sacrilege. He experience which he underwent was much the same as Luther’s when he remembered with such unfeigned horror and disgust the vows which he had pronounced on entering the convent. P. 10

- Plato, too, knew the “underground”, but her called it a “cave” and created his splendid world-famous myth in which men were likened to prisoners in a cave. But he did it in such a way that no one thought of calling Plato’s cave “underground” nor calling Plato himself a sickly, abnormal being, one of those for whom normal men have to invent theories, treatments, etc. p. 13

- When he was in the settlement Dostoievsky was already especially attracted by these resolute men whom no obstacle could turn from their purpose. He tried by every means in his power to understand their psychology, but he did not succeed. P. 19

- Directly Kant hears the word “law” pronounced he takes his hat off; he neither wishes nor dares to dispute. He who says “law” says “power”; he who says “power” says “submission” – for man’s supreme virtue is to submit himself. P. 23

- Dostoievsky was not the first to live though this unimaginably terrible passage from one world to another and to find himself obliged to abandon the stability which “principles’ give. Fifteen hundred years earlier Plotinus, who had also tried to transcend our experience, tells that at the first moment one has an impression that everything is disappearing, and has an overwhelming fear that only pure nothingness is left. P. 28

- Science is objective, indifferent; it does not consider whether a thing matters or not. It coldly casts its eye over the innocent and the guilty alike, knowing neither pity nor anger. But where there is no pity or indignation, where the innocent and the guilty are alike regarded with indifference, where all “phenomena” are merely classified and not qualified, there can be distinctions between the important and the insignificant. Science pretends to the certainty, the universality, and the necessity of its statements. P. 32

- What happens to the mind of the underground man has no resemblance at all to thinking, nor even to seeking. He does not think, he excites himself desperately, throws himself about, knocks his head against the wall. He inflames himself the whole time, dashing up to unknown heights of fury, to fling himself into God knows what abysses of despair. He has no control of himself; a force far greater than himself has him completely under its sway. P. 42

- [Dostoievsky] has taken everything from us; he has left us nothing but “twice two is four”. Will man be able to bear this? Can I bear it myself? Or will my “consciousness”; all human consciousness, be finally crushed under the burden. And then we shall not only feel, but see, if only for a moment, that “here” everything is but beginning, that that what begins here does not finish here, where there is as yet neither beauty, nor ugliness, nor good, nor evil, but only hot and cold, agreeable and disagreeable, where it is not liberty that reigns, but necessity, to which even God Himself is subject, where human will and reason are as unlike the will and reason of the Creator as the dog, the barking animal, is unlike the dog-star. P. 52

- Is it possible to escape from the curse of knowledge? Can man cease to judge and to condemn? Can he cease to be ashamed of his nakedness, ashamed of himself, or of his surroundings, like Adam and Eve before the serpent led them into temptation. This is the subject of the great discussion, which takes place in the “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” (The Brothers Karamazov) between the Cardinal Inquisitor, an old man of ninety in whom all human wisdom is incarnate, and God Himself. The old man has long been silent, ninety years long, but at last he can bear it no longer; he must speak. P. 75

The Last Judgment; Tolstoy's Last Words

[edit]- Tolstoy pitilessly stips himself before our eyes. There are few writers who show us truths like these. p. 85

- The Diary of a Madman is in a sense the key to Tolstoy's work. If it had not been written by Tolstoy himself, we should certainly have looked upon it as a calumny, since we are accustomed to look upon great men as the incarnation of all the civil and even the military virtues. p. 87

- Unvarnished truth, that truth which runs contrary to the vital needs of human nature, is worse than any lie. This is what Tolstoy thought when he wrote War and Peace, when he was still entirely possessed by Aristotle's ideas, when he was afraid of madness and the asylum and hoped that he would never have to live in an individual world of his own. p. 94

- Reason, which is based upon the world common to us all, which furnishes us with truths like "twice two is four" and "nothing happens without a cause" - this reason not only cannot justify and explain these new terrors and anxieties of Tolstoy's; it condemns them pitilessly as unreasonable, motiveless, arbitrary, and consequently unreal and visionary. p. 101

- When "the light of truth" appeared to Descartes, he immediately imprisoned his discovery within a logical formula: "Cogito, ergo sum." And the great truth perished, it gave nothing either to Descartes or to any one else. Yet it was he himself who taught: "De omnibus dubitandum." But then he ought first of all to have questioned the legitimacy of the pretensions of syllogistical formulae, which claim to be the only, invariable, expert appraisers of truth and error. Directly Descartes began to make deductions he forgot what he had seen. He forgot the cogito, he forgot the sum, in order to be sure of the ergo which has the power to constrain men's minds. p. 110

- For this solitary man, "chance", so despised and rejected by science and by "our ego", becomes the principal object of his search. He resolves to perceive, to treasure, and even to express that revelation which hides behind the accidental, which is invisible to a reason busied over earthly affairs and subservient to the exigencies of social existence. Such was Plotinus, the last great philosopher of antiquity. Such also was Tolstoy. p. 116

- Tolstoy himself would not have been able to recognize by day all that had been revealed to him in the darkness. Did he not declare his antagonism to St. Paul and the doctrine of salvation by faith? We know how angry he was with Nietzsche for his formula "beyond good and evil", which had resuscitated the forgotten teaching of the old apostle. And, indeed, in the "world common to all" men cannot live by faith; in this world works are esteemed, and necessary; in it men are justified, not by faith, but by works. p. 123

- Where is truth, where is reality? Over there at Grichkino, or here on this plain? Grichkino had ceased to exist for ever; must one then doubt the reality of its existence? And with it the reality of the existence of all the old world? Doubt everything? De omnibus dubitandum? But did great Descartes really doubt everything? No, Hume was right: the man who has once doubted all things will never overcome his doubts, he will leave for ever the world common to us all and take refuge in his own particular world. De omnibus dubitandum is useless; it is worse than storm and snow, worse than the fact that Nikita is freezing and that the bay is shivering in the icy wind. p. 131-132

Revolt and Submission

[edit]- For a sick man we call the doctor, for a dying man the priest. The doctor endeavours to preserve man for mortal existence, the priest gives him the viaticum for eternal life. And as the doctor's business has nothing in common with the priest's, so there is nothing in common between philosophy and science. They do not help one another, they do not complement one another, as is usually assumed - they fight against one another. And the enmity is the more violent because it generally has to be hidden under the mask of love and trust. p. 142

- To ascribe a purpose, even the most modest, the most unimportant, to Nature, is to equate her activity with that of a human being. At bottom it is indifferent whether one assumes that Nature's aim is to preserve the organism or to create a saintly, virtuous, human being. p. 152

- Spinoza taught, and his commandments were received as a new revelation. And no one noticed (men prefer not to notice) that Spinoza himself acted, both as man and philosopher, in the diametrically opposite way. He asked no questions which he did not need, and found no answers which did not concern him. p. 159

- How alarming to men, even today, is Protagoras's doctrine that man is the measure of all things! And what efforts human thought makes to kill Protagoras and his teaching! They have stopped at nothing, not even at direct calumny - even men like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle who loved uprightness and honesty with their whole souls and honestly desired only to serve the truth. They were afraid that if they let Protagoras prevail, they would become misologoi, despisers of reason, that they would commit spiritual suicide. They were afraid: that is the point. But there was no reason to be afraid. p. 166

- It is only the modern, or rather, the most modern philosophy, which found the solution of the question in positivism à la Kant and Comte; to forget plagued and poisoned truth and live for the positive necessities of the next day, year or decade. This terms itself "idealism". It is, of course, also idealism of the purest water which has so possessed the spirit of modern man. The idea is the only god which has not yet been cast down from its pedestal. Scientists worship it no less than philosophers and theologians. p. 172

- One word more on Hegel. In his "logic" he gives this commandment to the philosopher: Thou shalt free thyself from all that is personal, raise thyself above all that is individual, if thou wouldst be a philosopher. Hegel held himself for a philosopher; does this mean that he obeyed his own commandment; that if, let us say, he had lived in our day, he would "quietly" have accepted all the misfortune which overwhelmed his fatherland? One could take twice and thrice as many striking examples to show how hard - indeed, how impossible - it is to test the sincerity and conscientiousness of the utterance even of philosophers who are justly esteemed as vessels of philosophic thought. p.180

- Time is infinite, space is infinite, there are innumerable worlds, life's riches and its terrors are inexhaustible, the secrets of the universal structure are incomprehensible - how can an entity hemmed in between so many eternities, infinities, unlimited possibilities, know what it has to do, and how can it choose for itself? Plato, indeed, allowed anamnesis - the recollection of what was in previous lives - but only to a very limited degree. p. 200

- De omnibus dubitandum, taught Descartes - doubt all things. Easily said - but how to do it? Try, for example to doubt that the laws of nature are always binding: one day a case may occur where nature makes an exception for some stone, and exempts it from the law of gravity. But how to find this stone, if one has the courage to admit such a possibility, even if one knew definitely that such a stone existed? p. 215

- Plotinus never laughs, he does not even smile. He is solemnity incarnate. His whole task - in this he is continuing and complementing the work of Socrates, "the wisest among men" - consists in detaching man from the outer world. The inner joys, inner contentment, are, he teaches, quite independent of the conditions of our outward existence. The body is a prison wherein the soul resides. The visible world is the wall of this prison. So long as we let our spiritual welfare depend on our jailers, we can never be "happy". p. 242

On The Philosophy of History

[edit]- The first commandment of modern philosophy runs: Thou shalt emancipate thyself from all postulates. The postulate has been declared a deadly sin, and he who makes one is the enemy of truth. p. 247

- We have thus two legends. Man as individual being came into the world in accordance with God's will and with His blessing. Or, individual life appeared in the universe against God's will and is therefore in its essence impious, and death, annihilation, is the just and natural punishment for the sinful self-will. How and by whom shall it be decided where the truth lies? p. 254

- Everyday experience teaches us that good and ill fortune befall in like measure the godless and the pious, the virtuous and the vicious. This is so, this was so, this will be so. Consequently also, it must be so, for this proceeds from the necessity of the divine nature and there is neither need nor possibility to alter the existing order of things. (Hegel said then: What is real is rational.) Must virtue be rewarded? Virtue is its own reward. p. 268

Gethsemane Night - Pascal's Philosophy

[edit]- Pascal feared novelty above all things. All the strength of his restless, yet profound and concentrated mind, was applied to resisting the current of history, preventing himself from being carried forward by it. Is it possible, is it reasonable to fight against history? Of what interest to us can a man be, who tries to make time run backwards? p. 274

- We burn with longing to find some firm stance, some ultimate, unshakable basis, on which we may build the tower that can reach up to infinity. But all our foundations crack and earth opens to the abyss. THEREFORE LET US NOT SEEK CERTAINTY OR SECURITY. p. 284-285

- It is certain that Pascal never passed a day without suffering, and hardly knew what sleep was (Nietzsche's case was the same); it is also certain that Pascal, instead of feeling the solid earth beneath his feet as other men do, felt himself hanging unsupported over a precipice, and that had he given way to the "natural" law of gravity he would have fallen into a bottomless abyss. All his Pensées tell us this, and nothing but this. p. 291

- One may say with some certainty that Pascal would have remained the Pascal of the Provinciales had it not been for the abyss. So long as a man feels the solid earth beneath his feet, he will not risk defying reason and morality. Only exceptional conditions of being can free us from the immaterial and eternal truths which rule the world. Only a "madman" declares war on this rule. Remember the "experience" of our contemporary Nietzsche who begged the gods for "madness", since he had to kill the law, or, to use his own words, to announce to Rome and the world that he was "beyond good and evil". p. 305

- The fundamental condition of the possibility of human knowledge consists in the fact that truth can be perceived by any normal man. Descartes had thus formulated it: God neither can nor wishes to cheat. Pascal, on the other hand, maintains that God both can be and wishes to be a cheat. Sometimes, to certain people, He reveals the truth; but He deliberately blinds the greater number of them in order that they should not perceive the truth. Who is right, Pascal or Descartes? p. 317

Words That Are Swallowed Up - Plotinus's Ecstasies

[edit]- "In so far as the soul is in the body it rests in deep sleep," says Plotinus (III,vi,6). For a century past Plotinus's doctrine has been attracting increasing attention from philosophers. New works on Plotinus are continually appearing, and each fresh examination is another hymn in his praise. p. 327

- To understand Plotinus's thought we have to study his writings, to read them not once but many times, and to seek precisely for that definition which he tries in all ways to avoid. In other words, to study Plotinus means to kill him, and not to study him means to renounce him. What is to be done? how can we find a way out of this absurd position? p. 335

- philosophy can never reconcile itself with science. Science aims at self-evident truths and finds in them that "natural necessity" which, after having proclaimed itself for ever eternal, claims to serve as the foundation of all knowledge and strives to rule over all wanton "suddenly". But philosophy has always been, and will always be, a fight with and a conquest of self-evident truths; philosophy is not looking for any "natural necessity", it sees in naturalness and in necessity alike an evil magic, which, if one cannot quite shake it off (for in this no mortal has ever yet succeeded), yet one must at least call by its right name; and even this is an important step! p. 342

- Plotinus's assertion that the soul, in so far as it is in the body, rests in deep sleep, now acquires a new meaning for us; Plotinus, like his great predecessors Epictetus, Plato, and Socrates, felt that we must awake out of something, overcome some self-evident truths. We must discover the magician who holds the souls of men under his spell. Where is he? How fight against him? p. 349

- Plotinus and Pascal, each in his day, saw the "supernatural" power and felt it with all their souls. This force was enchanting man by convincing him of the "natural necessity" and the infallibility of reason which offered man eternal and universally valid truths. p. 364

External Links

[edit]- In Job's Balances Archive.org borrow the book