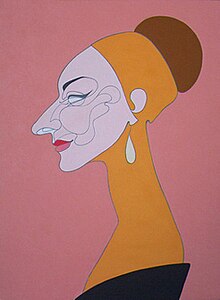

Maria Callas

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Maria Callas [Μαρία Κάλλας] (born 2 December 1923 – 16 September 1977) was an American-born Greek soprano opera singer.

Quotes[edit]

- Some say I have a beautiful voice, some say I have not. It is a matter of opinion. All I can say, those who don't like it shouldn't come to hear me.

- Television interview with Norman Ross, Chicago (17 November 1957)

- I admire Tebaldi's tone; it's beautiful — also some beautiful phrasing. Sometimes, I actually wish I had her voice.

- Discussing rival soprano Renata Tebaldi, in a television interview with Norman Ross, Chicago (17 November 1957)

- What [Tullio Serafin] said that impressed me was: "When one wants to find a gesture, when you want to find how to act on stage, all you have to do is listen to the music. The composer has already seen to that." If you take the trouble to really listen with your soul and with your ears — and I say soul and ears because the mind must work, but not too much also — you will find every gesture there. And it is all true, you know.

- On advice from Tullio Serafin, in "Harewood Conversations - 1968", an interview in Paris with Lord Harewood for the BBC (April 1968) on Maria Callas : The Callas Conversations (2004) EMI Classics DVD

- What a lovely voice, but who cares?

- On hearing a recording by Renata Tebaldi, as quoted in The Last Prima Donnas (1982) by Lanfranco Rasponi; also in The Book of Musical Anecdotes (1985) by Norman Lebrecht ISBN 0-02-918710-9

- Don't talk to me about rules, dear. Wherever I stay I make the goddamn rules.

- On her controversial personality and performance, quoted in Wild Women Talk Back : Audacious Advice for the Bedroom, Boardroom, and Beyond (2004) by Autumn Stephens, p. 142

Callas : The Art and the Life (1974)[edit]

- Quotes of Callas from Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin ISBN 0-03-011486-1

- Bel canto does not mean beautiful singing alone. It is, rather, the technique demanded by the composers of this style — Donizetti, Rossini, and Bellini. It is the same attitudes and demands of Mozart and Beethoven, for example, the same approach and the same technical difficulties faced by instrumentalists. You see, a musician is a musician. A singer is no different from an instrumentalist except that we have words. You don't excuse things in a singer you would not dream of excusing in a violinist or pianist. There is no excuse for not having a trill, for not doing the acciaccatura, for not having good scales. Look at your scores! There are technical things written there to be performed, and they must be performed whether you like it or not. How will you get out of a trill? How will you get out of scales when they are written there, staring you in the face? It is not enough to have a beautiful voice. What does that mean? When you interpret a role, you have to have a thousand colors to portray happiness, joy, sorrow, fear. How can you do this with only a beautiful voice? Even if you sing harshly sometimes, as I have frequently done, it is a necessity of expression. You have to do it, even if people will not understand. But in the long run they will, because you must persuade them of what you're doing.

- It takes a little more time to get into the role, but not very much more. In making a record you don't have the sense of projection over a distance as in an opera house. We have this microphone and this magnifies all details of a performance, all exaggerations. In the theater, you can get away with a very large, very grand phrase. For the microphone, you have to tone it down. It's the same as making a film, your gestures will be seen in close-up, so they cannot be exaggerated as they would be in a theater.

- On making studio recordings

- [Serafin was] an extraordinary coach, sharp as a vecchio lupo [old wolfe]. He opened a world to me, showed me there was a reason for everything, that even fiorature and trills ... have a reason in the composer's mind, that they are the expression of the stato d'animo [state of mind] of the character — that is, the way he feels at the moment, the passing emotions that take hold of him. He would coach us for every little detail, every movement, every word, every breath. One of the things he told me — and this is the basis of bel canto — is never to attack a note from underneath or from above, but always to prepare it in the face. He taught me that pauses are often more important than the music. He explained that there was a rhythm — these are the things you get only from that man! — a measure for the human ear, and that if a note was too long, it was no good after a while. A fermata always must be measured, and if there are two fermate close to one another in the score, you ignore one of them. He taught me the proportions of recitative — how it is elastic, the proportions altering so slightly that only you can understand it. ... But in performance he left you on your own. "When I am in the pit, I am there to serve you, because I have to save my performance." he would say. We would look down and feel we had a friend there. He was helping you all the way. He would mouth all the words. If you were not well, he would speed up the tempo, and if you were in top form, he would slow it down to let you breathe, to give you room. He was breathing with you, living the music with you, loving it with you. It was elastic, growing, living.

- I would not kill my enemies, but I will make them get down on their knees. I will, I can, I must.

Quotes about Callas[edit]

June Anderson[edit]

- I happen to think that Callas was the greatest singer of the 20th century. I feel that so many people have learned the wrong things from her, rather than the right things. She was a fabulous musician. When you listened to her, you could almost take dictation. All the dots were there. Anything that was wrong was because of the deterioration of the instrument over time. But usually musical things were not wrong. She has pitch problems and wobbles that came in later.

- Callas was such an example of professionalism. One thinks of her as a flighty diva, which is the wrong thing to learn from her, and she wasn’t at all.

- From Callas, I learned to respect the music. It’s part of the attention to detail. Today, everything seems to me a bit homogenized. Puccini sounds like Handel which sounds like Bellini. Callas had this sense of style, whether it was learned or just innate.

- Callas was superhuman. She was on a whole other plane. She really was a Diva — the goddess — and the rest of us are basically her handmaidens.

- "The Enduring Legacy of Maria Callas", Jason Victor Serinus, San Francisco Classical Voice, Jan 2, 2012 (https://www.sfcv.org/article/the-enduring-legacy-of-maria-callas)

John Ardoin[edit]

- That is such a difficult question. There are times when certain people are blessed — and cursed — with an extraordinary gift, in which the gift is almost greater than the human being. Callas was one of these people. It was as if her own wishes, her life, her own happiness were all subservient to this incredible, incredible gift that she was given, this gift that reached out and taught us things about music that we knew very well, but showed us new things, things we never thought about, new possibilities. I think that is why singers admire her so. I think that’s why conductors admire her so. I know it’s why I admire her so. And she paid a tremendously difficult and expensive price for this career.

- I don’t think she always understood what she did or why she did it. She knew she had a tremendous effect on audiences and on people. But it was not something she could always live with gracefully or happily.

- I once said to her “It must be a very enviable thing to be Maria Callas.” And she said, “No, it’s a very terrible thing to be Maria Callas, because it’s a question of trying to understand something you can never really understand.” She couldn’t really explain what she did. It was all done by instinct. It was something embedded deep within her.

- John Ardoin replying to Patsy Swank upon being asked, "Was it worth it to Maria Callas? She was a lonely, unhappy, often difficult woman." in Callas, A Documentary (1978), Extra Features, by John Ardoin, Bel Canto Society DVD, BCS-D0194

Martina Arroyo[edit]

- I adored this lady, and I respected her work ethic. She always wanted to improve her understanding of a piece. "Casta Diva", [for instance] — what interested me most was how she gave the runs and the cadenzas words. That always floored me. I always felt I heard her saying something — it was never just singing notes. That alone is an art. It’s an art that you can try to achieve, but you can’t copy, because that’s just imitating without delving into [how she felt] about that particular fioritura. ... how many other artists since Callas have you heard and thought, "She sang gorgeously, but I never cried?"

- Martina Arroyo, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Cecilia Bartoli[edit]

- Maria Callas remains an icon with an instantly recognizable voice. But she was also the first opera singer to be equipped with the ingredients of international celebrity: charisma, glamour, wealth, she had it all, together with the touches of scandal and tragedy that made her story so compelling. Since her time, every female opera singer has been measured against this powerful role model. ... Callas modernized our metier. Her life was a tireless creative search. She was one of the first to recognize the importance of being an actress as well as a singer, and was uncompromising in her belief that, in order to achieve a complete dramatic performance, all aspects of the operatic genre require equal attention. She was a pioneer in restoring forgotten repertoire and in exploring new ways of musical interpretation. To this day, I find that many of her exemplary recordings are astounding.

Carlo Bergonzi[edit]

- Callas studied the text, the meaning of the words, and as a result, she became a diva. She became the Great Callas. Because she studied the character, she entered the mind of the character, and she brought the character to life onstage. Today, young singers don’t have this mindset. They don’t have the kind of technique that Callas had. ...Price, Milanov and Tebaldi had stupendous voices and great careers. [But] Callas, as a performer, as someone who expressed the real meaning of the words, was the best. The best. There is no doubt about this — not only for her sound, but because she studied so much. Callas is the diva. She is important to young singers, because she was a serious singer onstage, and she left a great legacy. I don’t know, though, if they can listen and learn from what she left on her recordings.

- Carlo Bergonzi, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005); interview conducted, transcribed, and translated by Bob Kingston

Leonard Bernstein[edit]

- Callas? She was pure electricity.

- Leonard Bernstein, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

Montserrat Caballé[edit]

- She opened a new door for us, for all the singers in the world, a door that had been closed. Behind it was sleeping not only great music but great idea of interpretation. She has given us the chance, those who follow her, to do things that were hardly possible before her. That I am compared with Callas is something I never dared to dream. It is not right. I am much smaller than Callas.

- Montserrat Caballé, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

Natalie Dessay[edit]

- I used to listen again and again to recordings by Maria Callas. She was so musical and so theatrical at the same time. That is rare! I admire the way she cares for the words, so that everything comes from the text. She takes everything from the text and the music to elaborate a character and make her really interesting and impressive. She brings her own nature to the part — what she is, her passion, her fragility, doubts, feelings, violence — everything she is. And she never betrays the text or the music. We're very different, thank goodness, and I am happy with my own voice. But I feel very close to her in terms of discipline — trying to be as disciplined as she. She is an example to follow! Maybe in the past, people were more interested in voice and beautiful sounds. Maria Callas changed that. She arrived, brought a new way of doing opera, opened the way for us. We don't have any excuse now for not doing it!

- Natalie Dessay in "Mad About the Girl" by David J. Baker in Opera News vol. 72, no. 3, (September 2007)

Giuseppe Di Stefano[edit]

- Callas, way above the rest. Tebaldi had a fantastic voice, like an angel's. But even when Callas's voice wasn't perfect, she had so much interpretation. Opera is storytelling. Feelings must be conveyed. Acting must be moving. And Callas had it all.

- Giuseppe Di Stefano, upon being asked about his his favorite onstage partners; as quoted in "Stages of di Stefano" by Jonathan Kendall in Opera News (January 2000) [1]

Leyla Gencer[edit]

- Maria had in her blood, in her veins, in her subconscious all the tradition of the Greek Tragedy. She was born that way. In fact, she had her best time during 10 years. That was very short. But the "Myth of La Callas" will continue for ever, because she did so much! She was a magnetic force on stage, the others didn't exist anymore. It's a gift of Nature, a gift of God. It' a talent, a great talent.

- Leyla Gencer in recorded interview, available on http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9G2n_KkQtak&feature=related.

John Huston[edit]

- Oh, many. A few, even superior. For sheer strength of character, I wouldn't have dared to cross swords with Callas. I would rather have gone six rounds with Jack Dempsey!

- Response by John Huston, on being asked if he had ever met any woman who was his equal, as quoted in Playboy magazine (September 1985)

Evelyn Lear[edit]

- The Chicago Lucia [1954], which I witnessed, absolutely blew everybody's mind, because she stopped the show in the middle of the mad scene. She bowed, [while] the audience went wild, and kept that pose for fourteen minutes. Callas was our lesson, in those days, for how one performed. She had such complete ... we say in German "souveränität" — being above everything. She had this aura of magic. People were always mystified by what she did....Tebaldi had a much more beautiful voice and didn’t have that hollow, breathy sound, which at times was just plain ugly. [But] Callas was unusual because despite the sound of her voice, the force of her personality just magnetized people. It was so present, it came across the footlights at you, that ferocity of hers. It was just all-encompassing. Callas brought the personality, the drama, the magic, the surreal quality to the bel canto roles that Sutherland never did.

- Evelyn Lear, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Norman Lebrecht[edit]

- It seems almost inexplicable that the human race, with its ravenous appetite for entertainment, should have failed over so many decades to produce another Callas and Elvis. Neither Pavarotti nor Madonna come close, nor ever will. The desperate efforts of a universal music industry have yielded nothing more enduring than Cecilia Bartoli, the mini-voiced mezzo who tops the opera charts, and the high-kicking, faintly archaic Kylie Minogue, who belongs more to the smiley era of the Andrews Sisters than to the grim virtual reality of Bill Gates. In fact, when we commemorate the Presley and Callas anniversaries, one month apart, we confirm a catastrophic failure of cultural renewal.

- Norman Lebrecht, for the Evening Standard

Catherine Malfitano[edit]

- In all her recordings, one witnesses this incredible technique at work, whether it is Puritani, Sonnambula, Lucia, Norma or Abduction, [or] turning around to sing Gioconda and Kundry. This ability to devour all of vocal music history, and take it into herself and spew out such excellent examples of all these different styles — you just think, “How is a voice able to encompass all of this?” Well, it’s not the voice, it’s the woman behind the voice.

- No coloratura or fioritura was ever done for its own sake — it was always at the service of some expressive challenge....Her runs always gave the impression of being done so effortlessly. I liken it to the greatest ballerinas — they never made you aware of how painful it is to be en pointe. Callas transcended and transformed pain and difficulty into sheer weightlessness and ease and joy. It's absolute perfection in itself, and then on top of that she overlays expression — that's the thing I adored about this singer. She must have spent hours, days, weeks, years on this art, you know? The one I'm floored by is the Entführung that she did. ["Martern aller Arten"] is just beyond belief. I don’t think anyone has sung it better....

- There was some wonderful demonic thing that worked inside of her to fuse the elements of technique and expression and transcend the [roles she assayed.] ... She's an inspiration to everyone that follows her, but she’s also a kind of cautionary tale for artists, so they understand that you risk a great deal when you’re that hungry.

- Catherine Malfitano, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Aprile Millo[edit]

- Listening to Callas is like reading Shakespeare: you’re always going to be knocked senseless by some incredible insight into humanity. She is a huge bonfire! The thread, the "inner serpent" that she would get in certain music was so complete — for example, in the Lucia recording, the phrase "Alfin, son tua." Lucia, at her absolute happiest moment, would have said to Edgardo, "I am finally yours." For me, the woman Lucia came to life in that moment, and I understood why she was out of her mind, you know? You’ve got it all in that one phrase.

- Aprile Millo, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Ethan Mordden[edit]

- [Callas was] An outstanding historical figure, ranking with Malibran, Viardot, Toscanini, and Mahler. She is somewhat like Viardot, Chorley's "tones of an engaging tenderness" mingled with those "of a less winning quality." It was a flawed voice. But then Callas sought to capture in her singing not just beauty but a whole humanity, and within her system, the flaws feed the feeling, the sour plangency and the strident defiance becoming aspects of the canto. They were literally defects of her voice; she bent them into advantages of her singing. [Her voice] is what she had. What she made was a musical information of what was happening to her characters, a searching virtuosity. Suffering, delight, humility, hubris, despair, rhapsody — all this was musically appointed, through her use of the voice flying the text upon the notes....

- Yes, the woman could act. At the very moment she entered, you saw in full Aida, Anna Bolena, Gioconda, felt their eyes on you even before they uttered a sound. ... The gestures — so authentically antique, yet strangely devised entirely on her own — were completely equalized into her stylistics, with one set for the Greeks and Romans, another for post-Renaissance royalty, a third for more contemporary characters. Yet, all this was subsidiary to the heavy Kunst of developing the psychology of the roles under the supervision of the music, of singing the acting....

- She sang as if she had the most beautiful voice in the world — and sang so beautifully that she might as well have had such a voice. Thus she moved opera back a century to the age of Viardot, the acting singer.

- Ethan Mordden, in Demented : The World of the Opera Diva (1984)

Ewa Podles[edit]

- When I was around thirteen, fourteen years old, in communist Poland, we had no recordings at all. I don’t know how my mother found this old-fashioned recording, with Maria Callas, Tito Gobbi — you know, it was Tosca. I had only this one recording in my house, and I was listening to [it] ten times a day. I knew by heart everything — I could sing Cavaradossi, Tosca, Scarpia — each role. I was very young, and I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do in my life. And when I for the first time heard Maria Callas, suddenly I got proof — “Yes, I want to be a singer, I want to sing like she sings!”

- It’s enough to hear her, I’m positive! Because she could say everything only with her voice! I can imagine everything, I can see everything in front of my eye.

- People are funny, because they can’t be happy. If they have somebody like Maria Callas in front of them, they always try to find something wrong, something bad, a few mistakes, you know? And maybe she had three voices, maybe she had three ranges, I don’t know — I am professional singer. Nothing disturbed me, nothing! I bought everything that she offered me. Why? Because all of her voices, her registers, she used how they should be used — just to tell us something! She had a message for us, a fantastic message. She had such a big power, and then she just disappeared.

- Ewa Podles, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Leontyne Price[edit]

- Without hesitation, Maria Callas. . . Maria Callas gave me the opera bug. To pursue that area of placing my instrument, which I had already found out from me was not ordinary. I took a plane to Chicago, during the 50’s when she was there for the first time doing Madama Butterfly. And the excitement! Histrionically, she remade Opera, in the sense that she merged the sound with the action. Now, I’m not that kind of electric personality. but she taught me to fit my own movements, my own acceptance of claiming center-stage from her own doing that. It was one of the most exciting experiences I have ever known.

- Leontyne Price upon being asked, "Besides Marian Anderson, who were you inspired by?" as interviewed by NEA in 2008, available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGAg6OQXlQY

Nicola Rescigno[edit]

- I think the secret of Maria Callas was her willpower. Maria Callas was born with all sorts of disadvantages. Her voice was not of the most beautiful quality, and still, she made this instrument the most expressive, the most telling, the most true to the music that she interpreted. Maria was not born a beautiful woman. Maria was fat, obese, ungraceful — when you realize the type of body she was born with, like that of a pachyderm — but she turned herself into possibly the most beautiful lady on the stage.

- Nicola Rescigno, in Callas: A Documentary (1978) by John Ardoin, Bel Canto Society DVD, BCS-D0194.

- Maria had a way of even transforming her body for the exigencies of a role, which is a great triumph. In La traviata, everything would slope down; everything indicated sickness, fatigue, softness. Her arms would move as if they had no bones, like the great ballerinas. In Medea, everything was angular. She’d never make a soft gesture; even the walk she used was like a tiger’s walk.

- Nicola Rescigno in Callas, A Documentary (1978), Extra Features, by John Ardoin, Bel Canto Society DVD, BCS-D0194

Linda Ronstadt[edit]

- There's no one in her league. That's it. Period.

- Emmylou and I are both Maria Callas fans. We listen to that all the time. She's the greatest chick singer ever. I learn more about bluegrass singing, more about singing Mexican songs, more about singing rock-and-roll from listening to Maria Callas records than I ever would from listening to pop music for a month of Sundays.

Victor de Sabata[edit]

- If the public could understand, as we do, how deeply and utterly musical Callas is, they would be stunned.

- Victor de Sabata, as told to Walter Legge, quoted in Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth (1982). On and Off the Record: A Memoir of Walter Legge. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-684-17451-0.

- Maria, you are a monster; you are not an artist nor a woman nor a human being, but a monster.

- Victor de Sabata, regarding her timing and precision, as quoted in Maria Callas Remembered : An Intimate Portrait of the Private Callas (2000) by Nadia Stancioff, p. 98

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf[edit]

- That woman is a miracle!

- Elisabeth Schwarzkopf to Luchino Visconti upon hearing Callas singing "D'amor sull'ali rosee" in Il trovatore at La Scala in 1953 as quoted in The Callas Conversations, Vol. 2, (DVD) EMI Classics

- The greatest technician I ever met ! She could do everything.

- Elisabeth Schwarzkopf to Forumopera in 2002-3 [2]

Renata Scotto[edit]

- Listen to me, everyone talks about Callas. But I know Callas. I know Callas before she was Callas. She was fat and she had this vociaccia — you know what a vociaccia is? You go kill a cat and record its scream. She had this bad skin. And she had this rich husband. We laughed at her, you know that? And then, I sat in on a rehearsal with Maestro Serafin. You know, it was Parsifal and I was supposed to see if I made one of the flowers. I didn't. And she sang that music. In Italian of course. And he told her this and he told her that and little by little this voice grabed all the nature in itself — the forest and the magic castle and hatred that is love. And little by little she was not fat with bad skin and rich-husband-asleep-in-the-corner; she was the witch who burnt you by standing there. Maestro Serafin said to her afterwards "You know now something about Parsifal".She said, "No, Maestro, I know much more. I know how to study. And I know that we are more than voices. We are spirit, we are god when we sing, if we mean it." Oh yes, they will go on about Tebaldi this and Freni that. Beautiful, beautiful voices, amazing. They work hard. They sincere. They suffer. They're more talented than Maria, sure. But she was the genius. Genius come from genio — spirit. And that makes her more than all of us. So I learnt from that. Don't let them take from you because you are something they don't expect. Work and fight and work and give, and maybe once in a while you are good.

- Renata Scotto in recorded conversation with writer, vocal coach, and music critic Albert Innaurato

Francesco Siciliani[edit]

- In October of 1948, just after I moved to Florence to head the Teatro Comunale, Serafin called me from Rome. "Come at once," he begged. "You must hear this girl. She is discouraged and has bought a ticket to return to America. Help me convince her to stay." So, at his home, I met Maria Callas. She was tall and heavy, but had an interesting face, real presence, expression, intelligence.

With Serafin at the piano, she did her usual repertory for me — Gioconda, Turandot, Aida, Tristan. Parts of the voice were beautiful, other empty, and she used strange portamenti. During a pause, she said she had studied with Elvira de Hidalgo, which struck me as curious, for de Hidalgo had been a coloratura. "I know coloratura pieces too," Callas explained, "but I'm a dramatic soprano." "Well," I asked, "can we hear something of a different nature?" So she sang the aria from I Puritani, with the cabaletta. I was overwhelmed, and tears streamed down Serafin's cheeks. This was the kind of singer one read about in books from the nineteenth century — a real dramatic coloratura.- Francesco Siciliani, head of Teatro Comunale Florence and later Artistic Director of La Scala and music director for RAI, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

Patti Smith[edit]

- I've loved opera since I was a child. I study her; I mean of course I can't sing like that, but she has taught me a lot about discovering how to deliver the inner narrative of a song. Because I listen to her songs--I don't speak Italian or I don't speak whatever language she's singing--but I understand what she's conveying through her emotional interpretation.

- Patti Smith upon being asked why Maria Callas is such a great hero of hers, in conversation with Kurt Andersen on PRI's Studio 360 on December 24, 2009.

Frederica von Stade[edit]

- Callas’ magnificence lay in both her natural gift and her incredible commitment to mastering the correct style with the great conductors that she worked with. All the things that you think are happening spontaneously are planned and organized. They’re part of the style. Her stylistic mastery, as well as her personality and voice, still make people talk today. It’s that magic thing that happens.

- Whatever genius is, I think there’s a strong element of genius in [Callas].

- I didn’t dare study her phrasing, but of all the singers I listen to, it’s Callas I love most. I always have. And I was lucky enough to be at the Met[ropolitan Opera] when she did the master classes at Juilliard [School]. I saw them, and saw how she worked with people and what her knowledge was. There was no mystery to it. It was very tangible. The grounding was sort of like a ballerina’s footing in barre exercises. To get to the point where you get your feet to leap into the air, you have to begin very close to the floor. That’s what I think a lot of her musicianship represents to me: It’s her extraordinary devotion.

- "The Enduring Legacy of Maria Callas", Jason Victor Serinus, San Francisco Classical Voice, Jan 2, 2012 (https://www.sfcv.org/article/the-enduring-legacy-of-maria-callas)

Joan Sutherland[edit]

- [Hearing Callas in Norma in 1952] was a shock, a wonderful shock. You just got shivers up and down the spine. It was a bigger sound in those earlier performances, before she lost weight. I think she tried very hard to recreate the sort of “fatness” of the sound which she had when she was as fat as she was. But when she lost the weight, she couldn’t seem to sustain the great sound that she had made, and the body seemed to be too frail to support that sound that she was making. Oh, but it was oh so exciting. It was thrilling. I don’t think that anyone who heard Callas after 1955 really heard the Callas voice.

- [Backstage] she was wonderful; she was marvelous. She was easy-going and a worker. Oh my goodness! She rehearsed and rehearsed; always full-voice, never pushing the sound, but she would work till she got what was wanted. And of course had very poor eyesight. She used to pace out how many steps she would go, and there were steps and different levels on stage, as they were, in Norma. And she knew how many paces she could take before she had to take a step, because she was blind as a bat. She had terrible eyesight and, of course, couldn’t wear contact lenses at the stage. She did later.

- Joan Sutherland interviewed on BBC, and available on YouTube

Walter Taussig[edit]

- [Working with Callas was] like nothing else. Compared to nothing. I would say singers are reproductive artists, but she was a creative artist. She was in the role so much, it was fabulous, fabulous. She was very modest, very easy. But I think she saw red when she saw a journalist. But I could discuss a breath or anything with her. She didn't really have an ego when it came to the work. Her curse was that she was so musical, so intelligent, that she could take on roles that her voice couldn't handle. But what she did was always wonderful. There's a good example of what I mean. Callas — artist. Tebaldi — wonderful singer.

- Walter Taussig, long time coach at the Met), on working with Callas, as quoted in "The Associate" by Ira Siff in Opera News (April 2001)

Renata Tebaldi[edit]

- This rivality was really building from the people of the newspapers and the fans. But I think it was very good for both of us, because the publicity was so big and it created a very big interest about me and Maria and was very good in the end. But I don’t know why they put this kind of rivality, because the voice was very different. She was really something unusual. And I remember that I was very young artist too, and I stayed near the radio every time that I know that there was something on radio by Maria. The most fantastic thing was the possibility for her to sing the soprano coloratura with this big voice! This was something really special. Fantastic absolutely!

- Renata Tebaldi regarding Callas's voice and their supposed rivalry, quoted in Callas: A Documentary (1978) by John Ardoin, narrated by Franco Zeffirelli

Jon Vickers[edit]

- To work with her, you had to really understand how she saw your role, not how you saw it. She had a very clear-cut understanding of her role, and you had to fit into that interpretation. She was so great, [yet] she could not distance herself from a role. It was actually quite terrifying — she would at times actually cry while singing! You must only portray the emotions, not become personally involved. But Maria always became the role. She was such a servant of the text and the composer, she would tear her voice to ribbons to accomplish it!

- Jon Vickers, as quoted in "The Callas Legacy" by James C. Whitson in Opera News (October 2005)

Luchino Visconti[edit]

- I did it to serve Callas, for one must serve a Callas.

- Luchino Visconti commenting on his historic productions at La Scala, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

Antonino Votto[edit]

- The last great artist. When you think this woman was nearly blind, and often sang standing a good 150 feet from the podium. But her sensitivity! Even if she could not see, she sensed the music and always came in exactly with my downbeat. When we rehearsed, she was so precise, already note-perfect. ... For over thirty years, I was Arturo Toscanini's assistant, and from the very first rehearsal, he demanded every nuance from the orchestra, just as if it were a full performance. The piano, the forte, the staccato, the legato — all from the start. And Callas did this too. ... She was not just a singer, but a complete artist. It's foolish to discuss her as a voice. She must be viewed totally — as a complex of music, drama, movement. There is no one like her today. She was an esthetic phenomenon.

- Antonino Votto, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

David Webster[edit]

- About Maria Callas, I am honestly practically devoid of words. And that must be the case when one comes up against a phenomenon that one simply can't explain, but whom one appreciates. Indeed, as far as I'm concerned, I've been in love with her for years. She is, I think without any doubt at all, (and I don't mind what letters come to me tomorrow) the greatest theatrical, musical artist of our time.... She has an enormous feeling for music. She has an enormous feeling for words. She has an enormous feeling for the dramatic situation. She can convey all those things to an audience in a way that practically no other artist alive today can do.

- David Webster, introducing Callas at a 1962 concert at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden

Franco Zeffirelli[edit]

- The magic of a Callas is a quality few artists have, something special, something different. There are many very good artists, but very few who have that sixth sense, the additional, the plus quality. It is something which lifts them from the ground: they become like semi-gods. She had it. Nureyev has it, [Laurence] Olivier. But Olivier is also a case of an extremely rich knowledge of everything. He is completely coherent in his life, onstage. Whatever he does is part of a complete personality. Maria is a common girl behind the wings, but when she goes onstage, or even when she talks about her work or begins to hum a tune, she immediately assumes this additional quality. For me, Maria is always a miracle. you cannot understand or explain her. You can explain everything Olivier does because it is all part of a professional genius. But Maria can switch from nothing to everything, from earth to heaven. What is it this woman has? I don't know, but when that miracle happens, she is a new soul, a new entity.

- Franco Zeffirelli, as quoted in Callas : The Art and the Life (1974) by John Ardoin

External links[edit]

- Divina Callas's official website

- Callas Forever quotes at the Internet Movie Database

- Articles on Callas

- Discography

- Callas performances at YouTube