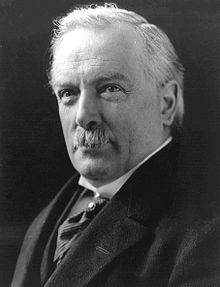

Michael Collins (Irish leader)

Appearance

(Redirected from Michael Collins)

Michael Collins (in Irish Mícheál Seán Ó Coileáin; 16 October 1890 – 22 August 1922) was an Irish revolutionary leader, Minister for Finance in the Irish Republic, Director of Intelligence for the IRA, and member of the Irish delegation during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations, both as Chairman of the Provisional Government and Commander-in-Chief of the National Army.

Quotes

[edit]

- When you have sweated, toiled, had mad dreams, hopeless nightmares, you find yourself in London's streets, cold and dank in the night air. Think — what have I got for Ireland? Something which she has wanted these past seven hundred years. Will anyone be satisfied at the bargain? Will anyone? I tell you this; early this morning I signed my death warrant. I thought at the time how odd, how ridiculous — a bullet may just as well have done the job five years ago.

- Letter, 6 December 1921. Cited in T. R. Dwyer, Michael Collins and the Treaty (1981), ch. 4, and Cathal Liam, Blood on the Shamrock (St. Padraic Press, 2006), p. 194

- Now as one of the signatories of the document I naturally recommend its acceptance. I do not recommend it for more than it is. Equally I do not recommend it for less than it is. In my opinion it gives us freedom, not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire and develop to, but the freedom to achieve it.

- Regarding the Anglo-Irish Treaty during a parliamentary debate (Dáil Éireann - Volume T - 19 December, 1921 (DEBATE ON TREATY))

- How could one argue with a man who was always drawing lines and circles to explain the position; who, one day, drew a diagram [here Michael illustrated with pen and paper] saying 'take a point A, draw a straight line to point B, now three-fourths of the way up the line take a point C. The straight line AB is the road to the Republic; C is where we have got to along the road, we canot move any further along the straight road to our goal B; take a point out there, D [off the line AB]. Now if we bend the line a bit from C to D then we can bend it a little further, to another point E and if we can bend it to CE that will get us around Cathal Brugha which is what we want!' How could you talk to a man like that?

- Referring to Eamon de Valera in conversation with Michael Hayes, at the debates over the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921

- Michael Hayes Papers, P53/299, UCDA

- Quoted in Gabriel Doherty and Dermot Keogh (2006) Michael Collins and the Making of the Irish State, Mercier Press, p. 153.

- There is no British Government anymore in Ireland. It is gone. It is no longer the enemy. We have now a native government, constitutionally elected, and it is the duty of every Irish man and woman to obey it. Anyone who fails to obey is an enemy of the people and must expect to be treated as such. We have to learn that attitudes and actions which were justifiable when directed against alien administration, holding its position by force, are wholly unjustifiable against a native government which exists only to carry out the people's will, and can be changed the moment it ceases to do so. We have to learn that freedom imposes responsibilities.

- A Path to Freedom (1968 [2010]), p. 14

- The Treaty is already vindicating itself. The English Die-hards said to Mr. Lloyd George and his Cabinet: "You have surrendered". Our own Die-hards said to us: "You have surrendered". There is a simple test. Those who are left in possession of the battlefield have won.

- A Path to Freedom (1968 [2010]), p. 23

- The European War, which began in 1914, is now generally recognized to have been a war between two rival empires, an old one and a new, the new becoming such a successful rival of the old, commercially and militarily, that the world-stage was, or was thought to be, not large enough for both. Germany spoke frankly of her need for expansion, and for new fields of enterprise for her surplus population. England, who likes to fight under a high-sounding title, got her opportunity in the invasion of Belgium. She was entering the war 'in defense of the freedom of small nationalities'. America at first looked on, but she accepted the motive in good faith, and she ultimately joined in as the champion of the weak against the strong. She concentrated attention upon the principle of self-determination and the reign of law based upon the consent of the governed. "Shall", asked President Wilson, "the military power of any small nation, or group of nations, be suffered to determine the fortunes of peoples over whom they have no right to rule except the right of force?" But the most flagrant instance of violation of this principle did not seem to strike the imagination of President Wilson, and he led the American nation- peopled so largely by Irish men and women who had fled from British oppression- into the battle and to the side of the nation that for hundreds of years had determined the fortunes of the Irish people against their wish, and had ruled them, and was still ruling them, by no other right than the right of force.

- A Path to Freedom (2010), p. 38

- Our army, if it exists for honorable purposes only, will draw to it honorable men. It will call to it the best men of our race- men of skill and culture. It will not be recruited as so many modern nations are, from those who are industrially useless.

- A Path to Freedom (1968 [2010]), p. 64

- We are a small nation. Our military strength in proportion to the mighty armaments of modern nations can never be considerable. Our strength as a nation will depend upon our economic freedom, and upon our moral and intellectual force. In these we can become a shining light in the world.

- A Path to Freedom (1968 [2010]), p. 64

Quotes about Collins

[edit]- In alphabetical order by author or source.

Rosary beads like teardrops on your fingers

Friends and comrades standing by, in their grief they wonder why

Michael, in their hour of need you had to go

Michael, in their hour of need, why did you go? ~ Johnny McEvoy

- We beat them in the cities and we whipped them in the streets

- And the world hailed Michael Collins, our commander and chief

- And they sent you off to London to negotiate a deal

- And to gain us a Republic, united, boys, and real

- But the women and the drink, Mick, they must have got to you

- 'cause you came back with a country divided up in two

- Black 47, Big Fellah (1989)

- We had to turn against you, Mick, there was nothing we could do

- 'Cause we couldn't betray the Republic like Arthur Griffith and you

- We fought against each other, two brothers steeped in blood

- But I never doubted that your heart was broken in the flood

- And though we had to shoot you down in golden Béal na mBláth

- I always knew that Ireland lost her greatest son of all

- Black 47, Big Fellah (1989)

- On January 21 they met in my room at the Colonial office, which, despite its enormous size, seemed overcharged with electricity. They both glowered magnificently, but after a short, commonplace talk I slipped away upon some excuse and left them together. What these two Irishmen, separated by such gulfs of religion, sentiment, and conduct, said to each other I cannot tell. But it took them a long time, and, as I did not wish to disturb them, mutton chops, etc. were tactfully introduced at about one o'clock. At four o'clock the Private Secretary reported signs of movement on the All-Ireland front and I ventured to look in. They announced to me complete agreement reduced to writing. They were to help each other in every way; they were to settle outstanding points by personal discussion; they were to stand ogether within the limits agreed against all disturbers of the peace.We three three then joined in the best of all pledges, to wit, 'To try to make things work'.

- Winston Churchill, describing a day in which Michael Collins of the emerging Irish Free State and Sir James Craig of the six counties of Northern Ireland met for the first time on 21 January 1922. As quoted by James Mackey in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 248-249

- From his earliest days Michael seems to have wanted to be the leader in everything that went on around him. His cousin Michael O'Brien wrote of him in their childhood days that Collins would always 'insist on running the show at Woodfield when we were kids, even to holding the pike (fork) when we endeavoured to spear salmon'. (There were only small trout in the river.) The family history abounds with doting anecdotes of the young Collins. Celestine, going away to be a nun in England, recalls the little boy waving goodbye until the pony and trap took her around the bend and out of sight. Mary tells of being left to look after the household for a day of drudgery during which she forgot to dig the potatoes until evening. Wearily forcing herself to the kitchen garden she was met by her three-year-old brother dragging behind him a bucket of potatoes that he had somehow managed to dig up by himself. Johnny remembers his prowess with horses, in particular, being found one day while still a baby curled up fast asleep in a stable between the hoofs of a notoriously vicious animal. His father on his deathbed told his grieving family to mind Michael because, 'One day he'll be a great man. He'll do great work for Ireland.' Michael was six years old at the time.

- Tim Pat Coogan Michael Collins: The Man Who made Ireland (1992), p. 9

- Dr. Cagney, who had served through the Great War and had 'a wide knowledge of bullet wounds' told McGarry that Collins was killed by a .303 rifle bullet. The bullet entered behind the left ear, making a small entrance wound, and exited above the left ear making 'a ragged wound' on the left side of his head. Collins' long hair hid the entrance wound. It was his fate to die, almost accidentally, in his home county, at the hands of men who admired him, in one of the most avoidable, badly organized ambushes of the period. Any one of his assailants could have fired the fatal shot. None of them would have been proud to do so.

- Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: The Man Who made Ireland (1992), p. 421

- What would have happened if Michael Collins had lived? This again is a question asked incessantly in Ireland and though I have already dealt exhaustively with questions of speculation, and hesitate to weary the reader with issues which, by definition, must be totally matters of opinion, some evaluation is called for. Obviously he had a greater grasp of economics than his contemporaries and would have brought more drive, efficiency and imagination to bear upon the task of building up the country after the civil war than did anyone in any government or party that came after him. My opinion, and it has to be based purely on speculation, is that Ireland would have benefited enormously had he lived. Unlike de Valera whose talent lay in getting and holding power, Collins asked himself the question, 'All this for what?', and tried to provide the answers. However practical or impractical his recorded thoughts may have been they were the thoughts of a still-young man, capable of great development; a man who, in the eye of the storm, was able to take time to try to plot a course for his people and his country.

- Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: The Man Who made Ireland (1992), p. 421-422

- De Valera paused before replying to the suggestion. It had been his Karma to live a long and distinguished public life. Although he was then in his eighty-fifth year he was looking forward to a second seven-year term as President of Ireland. But he knew that before the bar of history his name and fame were inextricably linked with a man whose allotted span had been destined to be but a third of his own. He knew that the story of Eamon de Valera could not be told without that of Michael Collins. Already he had embarked on what he knew in his heart was a futile effort to influence the record for the benefit of posterity. His newspaper and political empires had published innumerable favourable articles, histories and recollections. And in the years ahead he planned to ensure that much more favourable comment and chronology would be collated and set down. He had fashioned a vigorous dialectic of de Valerism that would bulwark him against critical re-appraisal long into the future. But de Valera was a realist, a man whose doodlings on the back of documents took the form of mathematical symbols. He realised only too well that his party, his newspapers, his Constitution even, had grown out of his opposition to Michael Collins and the resultant civil war. He knew that eventually, in the truthful telling of history, two and two would make four. Torn between his own clarity of vision and the myths he had spun around himself, de Valera struggled painfully for words to express himself. Then he said, 'I can't see my way to becoming Patron of the Michael Collins Foundation. It's my considered opinion that in the fullness of time history will record the greatness of Collins and it will be recorded at my expense.' He could be right.

- Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Collins: The Man Who made Ireland (1992), p. 432

- Republican and statesman. Born in Clonakilty, Co. Cork, Collins moved to London in 1906 where he worked as a clerk in the Post Office and later for a firm of stockbrokers. While in London he became involved with the Irish Republican Brotherhood. He returned to Ireland in 1915 and fought in the General Post Office during the rising of 1916. On his release he became increasingly influential in Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers. He was elected to the first Dáil for South Cork and for Tyrone, first becoming minister for home affairs and from April 1919 minister for finance. In the latter function he organized the Dáil Loan which financed the republicans' alternative government. As director of organization and intelligence for the IRA he played a leading part in the co-ordination of the military campaign in the Anglo-Irish War. His intelligence network in Dublin was renowned, and he was responsible for the 'Squad' which eliminated government intelligence. His success and determination to get things done brought him into conflict with some other leaders such as de Valera and Cathal Brugha.

- S.J. Connolly (editor), The Oxford Companion to Irish History (1998), p. 102

- Collins was a reluctant delegate to the negotiations that produced the Anglo Irish treaty, but accepted their outcome and was appointed chairman and minister for finance of the Provisional Government responsible for the establishment of the new Irish state. He regarded the treaty only as a means toward obtaining a 32-county republic. His conspiratorial nature came to the fore in his secret arrangement with the anty-treatyites to attack Northern Ireland while officially recognizing it. He became commander-in-chief of the Free State army when the Irish Civil War broke out, and was killed on 22 August 1922 at Beal na Blath, Co. Cork, during an inspection tour of the south. Generally seen as a man of action, he commanded great respect, admiration, and loyalty among those around him. He has been much idealized since his death, often described as the man who singe-handedly defeated the British forces. This view has been challenged in more recent writing. The widespread admiration for him has nevertheless, fuelled much speculation about what Ireland would have been like if he had lived. Such speculation emphasizes his view of the treaty as a stepping stone, his progressive social views, and his potential to reunite a divided republican movement.

- S.J. Connolly (editor), The Oxford Companion to Irish History (1998), p. 102

- It was widely believed there was a reward of £10,000 for the capture of Collins, which was as much as most Irish people could then expect to earn in a lifetime. The Black and Tans, for instance, were considered well paid, but the supposed reward amounted to more than they could earn in fifty years, working seven days a week and fifty-two weeks a year. As a result there was always the danger someone might betray Collins for the money.

- T. Ryle Dwyer, Michael Collins: The Man Who Won the War (1990), p. 129

- His engaging personality won friendships even amongst those who first met him as foes, and to all who met him the news of his death comes as a personal sorrow.

- David Lloyd George, in his message of sympathy to William Cosgrave, Acting Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State, in the aftermath of Collins' death. As quoted by James Mackay in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 296

- He was the man whose matchless energy, whose indomitable will, carried Ireland through the terrible crisis; and though I have not now, and never had, an ambition about either political affairs or history, if my name is to go down in history I want it to be associated with the name of Michael Collins.

- Arthur Griffith, giving a rebuttal to Cathal Brugha's attack on Michael Collins during the debates in the Dáil over the Anglo-Irish Treaty in January 1922. As quoted by James Mackay Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 240

- Collins' death can be put down to his devil-may-care attitude- his decision to journey through hostile territory in a large convoy, the inadequate choice of the members of the convoy, and the tactics he adopted in the ambush. For all the debate about ballistics and entry and exit wounds, it matters more that Collins was killed than how he was killed. Concentration on the events at Béal na mBláth has, moreover, often meant a failure to place them in the overall context of the war.

- Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (1988), p. 178

- The government had lost its one popular leader- the man who had made the Treaty's acceptance a probability. He has been all too easily glamourised, both by contemporaries and by historians; yet he remains, of all modern Irish national heroes, the one with whom ordinary people feel the greatest affinity. De Valera's appeal lay partly in his detachment and his remoteness; Collins, by contrast, was a back-slapper and a drinking companion. Both Cosgrave and Mulcahy were to admit that they also were vastly different characters from Collins- they could not hope to achieve Collins' personal appeal. Collins had dominated the army and government so much that he was clearly going to be difficult to replace. Though possessing much of Collins' dynamism and strength of purpose, O'Higgins was never to be remotely as popular.

- Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (1988), p. 178

- As Collins was only thirty-one at the time of his death, there has been much debate about whether he would have matured int a major statesman if he had lived, or whether he would have become a military dictator. He had shown considerable impatience with politicians and negotiations, often telling friends that he had little aptitude for politics. He did have definite administrative talents and great gifts of communication. He had demonstrated no desire to establish a military dictatorship. Collins had little consciousness of any need for wide-ranging social and economic change, despite being a severe critic of some aspects of Irish society. Major parts of his speeches were taken up with a simple articulation of Gaelic revivalism. Although they were genuinely alarmed about the possible consequences of Collins' death, British politicians and civil servants were to be relieved that they no longer had to deal with what Sir Samuel Hoare described as Collins' 'film-star attitudinising'. They were to contrast Cosgrave's straightforwardness and reliability with Collins' stridency. Anglo-Irish relations were to improve under Cosgrave and O'Higgins. The Northern government had every reason to be grateful for Collins' death. Collins could, perhaps, have helped to heal wounds within the Twenty-Six Counties- many believed that he would not have allowed an executions policy. He might well, however, have increased tensions between North and South in the post-war period. Meanwhile, for many old volunteers in the army the loss of their leader meant that their position appeared to be threatened, and it increased their fears that the old republican ideals were to be ignored.

- Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green: The Irish Civil War (1988), p. 179

- Where was Michael Collins during the Great War? He would have been worth a dozen brass-hats.

- Thomas Jones, British civil servant who served as Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet under four British Prime Ministers, as quoted by James Mackay in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 161

- I was allowed to paint him in death. Any grossness in his features, even the peculiar dent near the point of his nose, had disappeared. He might have been Napoleon in marble as he lay in his uniform, covered by the Free State flag, with a crucifix on his breast. Four soldiers stood around the bier. The stillness was broken at long intervals by someone entering the chapel on tiptoe, kissing the brow, and then slipping to the door where I could hear a burst of suppressed grief. One woman kissed the dead lips, making it hard for me to continue my work.

- Sir John Lavery on his work painting Michael Collins: Love of Ireland in 1922 following Collins' death. As quoted by James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 294

- Good luck be with you, Michael Collins

- Or stay or go you far away;

- Or stay you with the folk of fairy,

- Or come with ghosts another day.

- Sir John Randolph Leslie, 3rd Baronet, commonly known as Shane Leslie, on seeing Sir John Lavery's portrait Michael Collins, Love of Ireland, which was painted by Lavery following Collins' assassination on 22 August 1922. As quoted by James Mackay in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 265

- He passed the great test for any adult in that children loved him.

- P.S. O'Hagerty, in a statement after Collins' death. As quoted by James Mackay in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 296

- A concern for others would be an outstanding characteristic of Michael Collins to the end of his life, and it is idle to speculate that some of the worst excesses of the civil war, perpetrated after his death, might have been avoided. There are also many anecdotes that illustrate his total absence of fear, even as a very small child. These stories, however, probably reflect the attitudes of the raconteur rather than revealing the truth about Michael; for an absence of fear is a dangerous quality and this, indeed, may have been ultimately his undoing. Certainly, the story told by his brother Johnny, of the toddler wandering off and subsequently being found asleep amid the straw on the floor of the stall housing a vicious stallion which only old Michael John could control, suggests foolhardiness born of ignorance. Astonishingly, little Michael was found curled up, fast asleep, between the animal's hooves.

- James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 20

- From the beginning Michael was targeted by the anti-Treaty faction and as the sessions wore on the issue became not so much the Treaty itself, but the personal standing of Mick Collins. In the end, and to a very large extent, the voting reflected the love or hatred for him- there could be no half measures- of the individual deputies. During the stormy sessions, Michael was for the most part calm and dignified, even stoical at times; but now and then his famous temper would explode. Strangely enough, or perhaps characteristically, what seemed to rouse his ire most of all was the inability of deputies to arrive for each session on time, there by delaying the start of proceedings. With immense forcefulness he reminded them that punctuality was a great thing. Two factors were immediately apparent: the disagreement was set to divide opinion right across the country, and if Michael were the chief target of opprobrium he was not going to take it lying down.

- James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 230-231

- Seldom in the history of any country has a single unlucky bullet so utterly altered the course of events. Indeed, it would be no exaggeration to say that Ireland suffers the consequences to this day. Had Michael lived, it is highly probable that he would have brought the civil war to a speedy conclusion and succeeded in healing the breach with the North, leading t the removal of partition which few politicians, from Lloyd George and Churchill downwards, regarded as anything other than a purely temporary measure in 1922. After Michael's death, however, the South had no one with the breadth of vision and the negotiating skills to tackle Sir James Craig, and as time passed, the breach between North and South widened. Michael would almost certainly have prevented the Ulster boundary crisis of 1925, with its tragic consequences for Anglo-Irish relations over the ensuing seven decades. This arose when the report of the Boundary Commission was published, revealing that not an inch of Northern Ireland was to be ceded to the Free State, despite the wishes of at least a third of the inhabitants of the Six Counties. This bombshell reopened old wounds and almost triggered off a renewal of civil war in southern Ireland.

- James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 302

- In Glasnevin cemetery Michael is at rest in the plot reserved for the dead of Óglaigh na hÉireann, the Irish armed forces, from the civil war right down to soldiers killed on active service with the UN peace-keeping forces in many parts of the world. Somehow it seems fitting that Michael lies here among the warrior dead of Ireland.

- James Mackay, Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 303

- The curlew stood silent and unseen

- In the long damp grass

- And he looked down on the road below him

- That wound its way through Beal Na mBlath

- And he heard the young men shouting and cursing

- Running backwards and forwards

- Dodging and weaving and ducking the bullets

- That rained down on them

- From the hillside opposite.

- Just as quickly as it started the firing stopped

- And a terrible silence hung over the valley

- A lone figure lay on the roadside

- In the drizzling August rain

- Dressed in green cape coat, leggings,

- And brown hobnail boots

- That would never again

- Set the sparks flying from the kitchen flagstones

- As he danced his way through a half-set

- A hurried whispered act of contrition

- And the firing breaks out again

- The curlew takes to flight

- And as he flies out over the empty sad fields of West Cork

- With his lonesome call

- He must tell the world

- That the Big Fellow has fallen

- And that Michael is gone.

- Irish singer Johnny McEvoy, in his song Michael (1989)

- Candles dripping blood, they placed beside your shoulders

- Rosary beads like teardrops on your fingers

- Friends and comrades standing by, in their grief they wonder why

- Michael, in their hour of need you had to go

- Michael, in their hour of need, why did you go?

- Irish singer Johnny McEvoy, in his song Michael (1989)

- During the course of their negotiations, the British government made it clear that although they would concede Dominion status to Ireland, they would not coerce the newly created statelet of Northern Ireland into an all-Ireland republic or relinquish the strategically important naval bases. To press home the significance of these ports, Lloyd George invited the Royal Navy's most distinguished officer, Admiral Beatty, to impress upon Michael Collins their importance to Britain. According to Winston Churchill, during the course of these discussions with Admiral Beatty, Collins commented "Of course you must have the ports- they are necessary for your life." Collins knew that in the recent war Britain had lost over 11 million tons of merchant and naval shipping. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Collins was no doctrinaire nationalist but a courageous pragmatist who had a clear grasp of the strategic value of these naval facilities to Britain. He seemed to appreciate that the British could not and would not concede on the issue of naval facilities in Ireland.

- Aidan McIvor A History of the Irish Naval Service (1994), p. 39

- My Dear Miss Collins- Don't let them make you miserable about it: how could a born soldier die better than at the victorious end of a good fight, falling to the shot of another Irishman- a damned fool, but all the same an Irishman who thought he was fighting for Ireland- 'A Roman to a Roman'? I met Michael for the first and last time on Saturday last, and am very glad I did. I rejoice in his memory, and will not be so disloyal as to snivel over his valiant death. So treat up your mourning and hang up your brightest colours in his honour; let us all praise God that he did not die in a snuffy bed of a trumpery cough, weakened by age, and saddened by the disappointments that would have attended his work had he lived.

- George Bernard Shaw, in a letter to Collins' sister Hannie on 25 August 1922, as quoted by James Mackay in Michael Collins: A Life (1996), p. 297

- Oh long will old Ireland be seeking in vain

- Ere we find a new leader to match the man slain

- A true son of Grainne his name long will shine

- O gallant Mick Collins cut off in his prime

- Irish rebel music band The Wolfe Tones, in their song Michael Collins (1983)