Microeconomics

Appearance

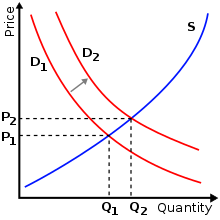

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and small impacting organizations in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources.

Quotes

[edit]- The dictionary defines "economics" as "a social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services." Here is another definition of economics which I think is more helpful in explaining how economics relates to software engineering.

- Economics is the study of how people make decisions in resource-limited situations.

- This definition of economics fits the major branches of classical economics very well.

- Macroeconomics is the study of how people make decisions in resource-limited situations on a national or global scale. It deals with the effects of decisions that national leaders make on such issues as tax rates, interest rates, foreign and trade policy.

- Microeconomics is the study of how people make decisions in resource-limited situations on a more personal scale. It deals with the decisions that individuals and organizations make on such issues such as how much insurance to buy, which word processor to buy, or what prices to charge for their products or services.

- Barry Boehm "Software engineering economics." Software Engineering, IEEE Transactions on 1 (1984): 4-21. p. 4.

- One of the most important skills of the economist, therefore, is that of simplification of the model. Two important methods of simplification have been developed by economists. One is the method of partial equilibrium analysis (or microeconomics), generally associated with the name of Alfred Marshall and the other is the method of aggregation (or macro-economics), associated with the name of John Maynard Keynes.

- Kenneth Boulding, The Skills of the Economist, 1958, p. 19.

- Microeconomics and macroeconomics are closely intertwined. Because changes in the overall economy arise from the decisions of millions of individuals, it is impossible to understand macroeconomic developments without considering the associated microeconomic decisions.

- N. Gregory Mankiw, Principle of Economics (6th ed., 2012). p. 27

- The field of economics is traditionally divided into two broad subfields. Microeconomics is the study of how households and firms make decisions and how they interact in specific markets. Macroeconomics is the study of economy wide phenomena. A microeconomist might study the effects of rent control on housing in New York City, the impact of foreign competition on the U.S. auto industry, or the effects of compulsory school attendance on workers’ earnings. A macroeconomist might study the effects of borrowing by the federal government, the changes over time in the economy’s rate of unemployment, or alternative policies to promote growth in national living standards. Microeconomics and macroeconomics are closely intertwined. Because changes in the overall economy arise from the decisions of millions of individuals, it is impossible to understand macroeconomic developments without considering the associated microeconomic decisions.

- N. Gregory Mankiw, Principle of Economics (6th ed., 2012). p. 27

- When we approach the study of business cycle with the intention of carrying through an analysis that is truly dynamic and determinate in the above sense, we are naturally led to distinguish between two types of analyses: the micro-dynamic and the macro-dynamic types. The micro-dynamic analysis is an analysis by which we try to explain in some detail the behaviour of a certain section of the huge economic mechanism, taking for granted that certain general parameters are given. Obviously it may well be that we obtain more or less cyclical fluctuations in such sub-systems, even though the general parameters are given. The essence of this type of analysis is to show the details of the evolution of a given specific market, the behaviour of a given type of consumers, and so on.

- In a paper on business cycles, Frisch was the first to use the words “microeconomics” to refer to the study of single firms and industries, and “macroeconomics” to refer to the study of the aggregate economy.

- "Ragnar Frisch." in: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. 2008. Library of Economics and Liberty. 20 July 2014.

- Microeconomics, including the study of individual choice and of group choice in market and nonmarket processes, has generally been considered a field science as distinct from an experimental science. Hence microeconomics has sometimes been classified as "non-experimental" and closer methodologically to meteorology and astronomy than to physics and experimental psychology... But the question of using experimental or nonexperimental techniques is largely a matter of cost, and generally the cost of conducting the most ambitious and informative experiments in astronomy, meteorology, and economics varies from prohibitive down to considerable. The cost of experimenting with different solar system planetary arrangements, different atmospheric conditions, and different national unemployment rates, each under suitable controls, must be regarded as prohibitive.

- Vernon L. Smith, "Relevance of laboratory experiments to testing resource allocation theory." Evaluation of Econometric Models. Academic Press, 1980. 345-377. p. 345.

- With computers acting as the stimulus, the theory of war was assimilated into that of microeconomics. . . . Instead of evaluating military operations by their product –that is, victory – calculations were cast in terms of input–output and cost effectiveness. Since intuition was replaced by calculation, and since the latter wasto be carried out with the aid of computers, it was necessary that all the phenomena of war be reduced to quantitative form. Consequently everything that could be quantified was, while everything that could not be tended to be thrown onto the garbage heap.

- Martin Van Creveld, Technology and War: From 2000 B.C. to the Present, New York, London: Free Press, Collier Macmillan, 1989, p. 246; as qtd. in Antoine Bosquet, “Cyberneticizing the American War Machine: Science and Computers in the Cold War”, p. 94