Monetarism

In monetary economics, monetarism is a school of thought that emphasises the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarists believe that variation in the money supply has major influences on national output in the short run and the price level over longer periods, and that objectives of monetary policy are best met by targeting the growth rate of the money supply rather than by engaging in discretionary monetary policy.

Quotes

[edit]- Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

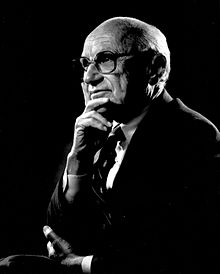

- Milton Friedman, The Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory (1970).

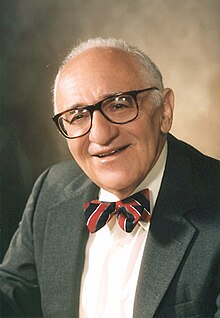

- Reagan had the opportunity to perform this quick surgery when he came into office. Instead, he turned his economic policies over to the Friedmanite monetarists. Reaganomics is largely monetarism. The monetarist view is that the Fed must only very, very slowly reduce the rate of counterfeiting, and thereby insure a gradual, painless recession with no unemployment or sharp readjustments. The hoax of Reaganomics was that the phony "budget cuts" and "tax cuts" were supposed to provide the razzle-dazzle to give gradualist Friedmanism the time, or the "breathing space," to work its magic. … There were two fundamental reforms the Reagan Administration could have proposed to end our Age of Inflation. First, either the abolition or the brutal checking of the Fed. Nothing was done, since monetarism wishes to give all power to the Fed and then navely urges the Fed to use that power wisely and with self-restraint. Second, the Administration could have followed Reagan's campaign pledge and reinstituted the gold standard. But the Friedmanite monetarists hate gold with a purple passion and wish all power to government fiat money.

- Murray N. Rothbard, "Are We Being Beastly to the Gipper? — Part III," Libertarian Forum XVI, no. 3 (April 1982), p. 6.

- Although there are deep and abiding differences between Chicago school monetarists and Austrian monetary theorists, there has always been strong agreement among them on one thing: the central importance of the money supply in explaining the purchasing power of money or "price level" in the economy.

This does not appear to be the case any longer. The June 2004 cover article of Monetary Trends a publication of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, long a staunch bastion of monetarism, is entitled "How Money Matters." A more accurate description of its contents is "Why Money Doesn’t Matter Anymore." The author, William T. Gavin, emphasizes that "money still matters"—just not its quantity.

- Joseph T. Salerno, "Money Matters No More?," Mises Daily (Auburn, AL: Lugwig von Mises Institute, 29 June 2004).

- Monetarism was a powerful force in economic debate for about three decades after Friedman first propounded the doctrine in his 1959 book A Program for Monetary Stability. Today, however, it is a shadow of its former self, for two main reasons.

First, when the United States and the United Kingdom tried to put monetarism into practice at the end of the 1970s, both experienced dismal results: in each country steady growth in the money supply failed to prevent severe recessions. The Federal Reserve officially adopted Friedman-type monetary targets in 1979, but effectively abandoned them in 1982 when the unemployment rate went into double digits. This abandonment was made official in 1984, and ever since then the Fed has engaged in precisely the sort of discretionary fine-tuning that Friedman decried. For example, the Fed responded to the 2001 recession by slashing interest rates and allowing the money supply to grow at rates that sometimes exceeded 10 percent per year. Once the Fed was satisfied that the recovery was solid, it reversed course, raising interest rates and allowing growth in the money supply to drop to zero.

Second, since the early 1980s the Federal Reserve and its counterparts in other countries have done a reasonably good job, undermining Friedman’s portrayal of central bankers as irredeemable bunglers. Inflation has stayed low, recessions—except in Japan, of which more in a second—have been relatively brief and shallow. And all this happened in spite of fluctuations in the money supply that horrified monetarists, and led them—Friedman included—to predict disasters that failed to materialize. As David Warsh of The Boston Globe pointed out in 1992, "Friedman blunted his lance forecasting inflation in the 1980s, when he was deeply, frequently wrong.

- Paul Krugman, "Who Was Milton Friedman?", The New York Review of Books (15 February 2007).

- Gore Vidal, the American writer, once described the American economic system as 'free enterprise for the poor and socialism for the rich'. Macroeconomic policy on the global scale is a bit like that. It is Keynesianism for the rich countries and monetarism for the poor.

- Ha-Joon Chang, "Keynesianism for the rich, monetarism for the poor," ch. 7 of Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism (2008).

- Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s monumental Monetary History of the United States eventually helped to displace Keynesian interpretations with a monetarist interpretation, especially after the stagflation of the 1970s worked to discredit Keynesian macroeconomics.

- Robert Higgs, "Debating the Great Depression: Steve Horwitz’s Latest Contribution," The Beacon (Independent Institute, 24 January 2011).

- Friedman's failure to see that monetarism would ultimately lead to the excesses of Keynesian tinkering in the economy is tragic, but the failure of so many today to recognize this is without excuse.

- Stefano R. Mugnaini, "My Nobel Prize," Mises Daily (Auburn, AL: Lugwig von Mises Institute, 7 July 2011).

- However, if Friedmanite monetarism was anything, it was naïve about political reality. The fatal flaw of Friedman's famous "monetary rule" of constant growth of the money supply in the 3–4 percent range was premised on the assumption that a machine-like Fed chairman would selflessly pursue the public interest by enforcing Friedman's monetary rule. According to Friedman, Stockman writes, "inflation would be rapidly extinguished if money supply was harnessed to a fixed and unwavering rate of growth, such as 3 percent per annum." This was the fundamental assumption behind monetarism, and it flew in the face of everything the Chicago Schoolers purported to know about political reality. In other words, Friedmanite monetarism was never a realistic possibility, for as Friedman himself frequently said of all other governmental institutions besides the Fed, a government institution that is not political is as likely as a cat that barks like a dog. Friedman's monetary rule, Stockman concludes, was "basically academic poppycock."

- Thomas J. DiLorenzo, "The Friedmanite Corruption of Capitalism," Mises Daily (Auburn, AL: Lugwig von Mises Institute, 31 May 2013).

- The world probably would have been much better off had macroeconomics never been devised. Although I have in mind Keynesian macroeconomics above all, I include other types of macro models as well. I even include, somewhat reluctantly, the whole quantity theory approach descended from David Hume to the Friedmanites, now known as monetarism. … In short, among its many other deficiencies, as spelled out by Mises and his followers, monetarism’s most fundamental flaw is identical to the most fundamental flaw of Keynesian, Post-Keynesian, New Classical, and other theories advanced by macroeconomists during the past seventy or eighty years: not only does the theory leave out critical variables, but it is too simple, being expressed in huge, all-encompassing aggregates that conceal the real economic action taking place within the economic order.

- Robert Higgs, "Is Macroeconomics Really Economics?," The Beacon (Independent Institute, 14 August 2014).

- Monetarism means honest money. It means that the money is backed properly by the production of goods and services.

- Margaret Thatcher, speech in the House of Commons (9 March 1982)

"Where the Monetarists Go Wrong" (1976) by Henry Hazlitt

[edit]Henry Hazlitt, "Where the Monetarists Go Wrong," The Freeman (Foundation for Economic Education, 1 August 1976).

- In the last decade or two there has grown up in this country, principally under the leadership of Professor Milton Friedman, a school calling itself the Monetarists. The leaders sometimes sum up their doctrine in the phrase: "Money matters," and even sometimes in the phrase: "Money matters most."

- It is with considerable reluctance that I criticize the monetarists, because, though I consider their proposed monetary policy unfeasible, they are after all much more nearly right in their assumptions and prescriptions than the majority of present academic economists. The simplistic form of the quantity theory of money that they hold is not tenable; but they are overwhelmingly right in insisting on how much "money matters," and they are right in insisting that in most circumstances, and over the long run, it is the quantity of money that is most influential in determining the purchasing power of the monetary unit. Other things being equal, the more dollars that are issued, the smaller becomes the value of each individual dollar. So at the moment the monetarists are more effective opponents of further inflation than the great bulk of politicians and even putative economists who still fail to recognize this basic truth.

- I do not mean to suggest that all those who call themselves monetarists make this unconscious assumption that an inflation involves this uniform rise of prices. But we may distinguish two schools of monetarism. The first would prescribe a monthly or annual increase in the stock of money just sufficient, in their judgment, to keep prices stable. The second school (which the first might dismiss as mere inflationists) wants a continuous increase in the stock of money sufficient to raise prices steadily by a "small" amount—2 or 3 per cent a year. These are the advocates of a "creeping" inflation. … I made a distinction earlier between the monetarists strictly so called and the "creeping inflationists." This distinction applies to the intent of their recommended policies rather than to the result. The intent of the monetarists is not to keep raising the price "level" but simply to keep it from falling, i.e., simply to keep it "stable." But it is impossible to know in advance precisely what uniform rate of money-supply increase would in fact do this. The monetarists are right in assuming that in a prospering economy, if the stock of money were not increased, there would probably be a mild long-run tendency for prices to decline. But they are wrong in assuming that this would necessarily threaten employment or production. For in a free and flexible economy prices would be falling because productivity was increasing, that is, because costs of production were falling. There would be no necessary reduction in real profit margins. The American economy has often been prosperous in the past over periods when prices were declining. Though money wage-rates may not increase in such periods, their purchasing power does increase. So there is no need to keep increasing the stock of money to prevent prices from declining. A fixed arbitrary annual increase in the money stock "to keep prices stable" could easily lead to a "creeping inflation" of prices.

- But this brings us to what I consider the fatal flaw in the monetarist prescriptions. If the leader of the school cannot make up his own mind regarding what the most desirable rate of monetary increase should be, what does he expect to happen when the decision is put in the hands of the politicians? … The fatal flaw in the monetarist prescription, in brief, is that it postulates that money should consist of irredeemable paper notes and that the final power of determining how many of these are issued should be placed in the hands of the government—that is, in the hands of the politicians in office. The assumption that these politicians could be trusted to act responsibly, particularly for any prolonged period, seems incredibly naive. The real problem today is the opposite of what the monetarists suggest. It is how to get the arbitrary power over the stock of money out of the hands of the government, out of the hands of the politicians.

"Is Milton Friedman a Keynesian?" (1992) by Roger Garrison

[edit]Roger W. Garrison, " Is Milton Friedman a Keynesian?," in Mark Skousen, ed., Dissent on Keynes: A Critical Appraisal of Keynesian Economics (New York, N. Y.: Praeger Publishers, 1992).

- While many of the conflicting claims can be reconciled in terms of the short-run and long-run orientation of Keynesians and monetarists, respectively, and in terms of their contrasting philosophical orientations, neither vision takes into account the workings or failings of the market mechanisms within the investment aggregate.

Austrian macroeconomics is set apart from both Keynesianism and monetarism by its attention to the differential effects of interest-rate changes within the investment sector, or—using the Austrian terminology—within the economy's structure of production.

- Page 136.

- Accounting for the artificial boom and the consequent bust is not part of Keynesian income-expenditure analysis, nor is it an integral part of monetarist analysis. The absence of any significant relationship between boom and bust is an inevitable result of dealing with the investment sector in aggregate terms. The analytical oversight derives from theoretical formulation in Keynesian analysis and from empirical observation in monetarist analysis. But from an Austrian perspective, the differences in method and substance are outweighed by the common implication of Keynesianism and monetarism, namely, that there is no boom-bust cycle of any macroeconomic significance.

- Pages 136–137.

An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (1995) by Murray N. Rothbard

[edit]

- Moreover, in 'macro', the scholastics, beginning with Buridan and culminating in the sixteenth century Spanish scholastics, worked out an 'Austrian' rather than monetarist supply and demand theory of money and prices, including interregional money flows, and even a purchasing-power parity theory of exchange rates.

- Introduction, p. xi (both vols.).

Economic Thought Before Adam Smith (vol. 1)

[edit]Murray N. Rothbard, An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought Volume 1: Economic Thought Before Adam Smith (Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 1995).

- Even more than William Potter, John Law assured the nation that the increased money supply and bank credit would not raise prices, especially under Law's own wise aegis. On the contrary, Law anticipated Irving Fisher and the monetarists by assuring that his paper money inflation would lead to 'stability of value', presumably stability of the price of labour, or the purchasing power of money. … The cataclysm of John Law's experiment and his Mississippi bubble provided a warning lesson to all reflective writers and theorists on money throughout the eighteenth century. As we shall see below, hard-money doctrines prevailed easily throughout the century, from Law's former partner and outwitter Richard Cantillon down to the founding fathers of the American Republic. But there were some who refused to learn any lessons from the Law failure, and whose outlook was heavily influenced by John Law.

- "The inflationists," §11.5 of ch. 5, "Mercantilism and freedom in England from the Civil War to 1750," pp. 329, 331.

- One of the superb features of Cantillon's Essai is that he was the first, in a pre-Austrian analysis, to understand that money enters the economy as a step-by-step process and hence does not simply increase or raise prices in a homogeneous aggregate.8 Hence he criticized John Locke's naive quantity theory of money—a theory still basically followed by monetarist and neoclassical economists alike—which holds that a change in the total supply of money causes only a uniform proportionate change in all prices. In short, an increased money supply is not supposed to cause changes in the relative prices of the various goods.

- "Money and process analysis," §12.7 of ch. 6, "The founding father of modern economics: Richard Cantillon," p. 355.

Classical Economics (vol. 2)

[edit]Murray N. Rothbard, An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought Volume 2: Classical Economics (Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., 1995).

- John Wheatley's exclusive emphasis on the money supply and unitary price levels foreshadowed the modern severe monetarist and macroeconomic split between the monetary and real realms. More pointedly, his mechanistic emphasis on the price level also foreshadowed the unfortunate Fisherine, Chicagoite and later monetarist preoccupation with stabilizing the 'price level' and with fanatically opposing any and all changes in such 'levels'. Even in his early books of 1803 and 1807, Wheatley denounced the alleged evils of falling prices as well as of inflation, and indeed claimed that falling prices were even more damaging. Indeed, the influence of Wheatley's early tracts was gravely weakened by his being soft-core and timid in drawing any policy conclusions from his hard-core analysis. Instead of returning to the gold standard, Wheatley could only suggest the withdrawal of note issue powers from the country banks and the redemption of all small bank notes under £5. … [A]s in the case of all too many monetarist and mechanistic quantity theorists, Wheatley began as an ardent hard-money bullionist, and was driven over the years by his frenetic hatred of deflation to wind up as a fiat money inflationist.

- "The emergence of mechanistic bullionism: John Wheatley," §5.8 of ch. 5, "Monetary and banking thought, I: the early bullionist controversy," p. 189.

- Christiernin, however, was far from a hard-core hard-money man. He defended bank notes as useful, increasing activity and employment, and opposed deflation because, he pointed out, prices and wages were sticky downward. It is doubtful, however, that downward stickiness could last for long in the eighteenth century. But Christiernin's main objection to deflation was that his ideal was not sound, metallic money but a pre-Friedmanite desire to stabilize the value of the daler and make the price level constant. In pursuit of that goal, he urged open market operations by the central bank. Furthermore, again in anticipation of the monetarists, he admittedly preferred inflation to deflation, if that was the choice.

- "Monetary and banking thought on the Continent," §6.5 of ch. 6, "Monetary and banking thought, II: the bullion Report and the return to gold," p. 220.

"Explaining Japan's Recession" (2002) by Benjamin Powell

[edit]Benjamin Powell, "Explaining Japan's Recession," Mises Daily (Auburn, AL: Lugwig von Mises Institute, 19 November 2002).

- The Austrian description of the boom's timing and cause seems similar to the monetarist theory, but there is an important difference. Both schools agree that the contraction of the monetary expansion triggered the recession, but the monetarists view this contraction as something that should be avoided so that prosperity can continue. In Austrian theory, the contraction is necessary to restore balance to the real economy—the preceding expansion is the problem. This is one reason why the two schools differ in their policy recommendations.

- Austrian theory, like the Keynesian and monetarist theories, can give a reason for the start of the Japanese recession. Unlike the other schools, the Austrian policy recommendation of laissez-faire has not been tried.

"In Defense of Monetarism" (2008) by George Selgin

[edit]

George A. Selgin, "In Defense of Monetarism," Mises Wire (Auburn, AL: Lugwig von Mises Institute, 11 November 2008).

- Although I realize that Austrian-school economists have themselves been highly critical of monetarism, many of its most fundamental claims are in fact fully consistent with their own understanding of monetary theory. Indeed, back in the 1970s the difference between Austrian and monetarists writings about money seemed trivial compared to the difference between them and the writings of other (broadly "Keynesian") economists. I recall very well how I myself got "deprogrammed" from mainstream thinking about money and inflation by reading Henry Hazlitt's wonderful book, The Inflation Problem, and How to Resolve It [sic]. Hazlitt was, of course, a thoroughgoing Misesian. Yet no one who reads his book can fail to note the many crucial similarities between his arguments and those of Milton Friedman concerning the same subject.

- Your friend, rather perversely I think, refers to the "disastrous results" that followed the monetary tightening of Volcker and other more monetarist-minded central bankers without even hinting at the facts that that the tightening was aimed at bringing down inflation rates, and that it succeeded remarkably well in doing precisely that. In other words, the tightening did precisely what monetarism said it would do, and what monetarists' critics at the time, wedded to the view that monetary policy was ineffective, and that inflation was entirely caused by OPEC (or by unions, or by anything except monetary policy) insisted it could not do. And yet your friend imagines that the experience proved the monetarists wrong!

- In one respect, however, I agree that monetarism was wrong, namely, to the extent that it failed to recognize the need to allow inflation to occur to the extent that it was solely due to falling output or productivity—a case I have argued, along with the symmetrical one for letting prices fall as productivity improves, in my IEA pamphlet Less Than Zero.

- It is indeed true that the reduction of inflation came at a big price—that Volcker's tightening, for instance, succeeded in lowering inflation only in the wake of a severe recession. But this possibility was, first of all, one concerning which monetarists were perfectly aware: they understood the danger that, once inflation, and accelerating inflation especially, came to be anticipated by the public, putting the breaks on money growth would result in prices and wages continuing for some time to rise beyond their new, less-rapidly rising equilibrium values, with a consequent rise in unemployment.

- No monetarist, certainly not Friedman, welcomed this side-effect of monetary restraint. But then again, had Friedman been listened to earlier (and had the likes of Paul Samuelson been ignored), things would never have come to this tragic stage. By way of analogy, should we blame those who would end the war in Iraq, and who opposed it all along, for the tragic consequences that are likely to follow any rapid U.S withdrawal?