Pat Conroy

Donald Patrick "Pat" Conroy (October 26, 1945 – March 4, 2016) was an American author who wrote several acclaimed novels and memoirs. Two of his novels, The Prince of Tides and The Great Santini, were made into Oscar-nominated films. He is recognized as a leading figure of late-20th century Southern literature. One of his best-known novels, The Lords of Discipline, depicts a fictionalized portrayal of Conroy's first-classman (senior) year at The Citadel in 1966-1967.

Quotes

[edit]

- Nancy Mace has written a wonderful, timeless memoir of the great test to become the first female graduate of The Citadel. Her book is provocative, hilarious, illuminating, and true. It is also a love letter to her college and the best book about The Citadel ever written.

- Conroy's praise for In The Company Of Men (2001), by Nancy Mace, first-ever female graduate of The Citadel, displayed on the back of the dust jacket for the hardcover edition.

- Virginia's Ring is a triumph and a tour de force. Lynn Seldon has written one of the best books about a military college ever written. With the publication of Virginia's Ring, he joins the distinguished ranks of our military academy graduates who have written about the life changing, fire tested tribe. It reminded me of James Webb's A Sense of Honor about the Naval Academy and Lucian Truscott's Dress Gray about West Point. But Mr. Seldon makes Virginia Military Institute a great test of the human spirit and one of the best places on earth to earn a college degree.

- Conroy's advance praise for the novel Virginia's Ring (2014), written and published by Virginia Military Institute, Class of 1983 graduate Lynn Seldon, printed on the first page in the book.

1970s

[edit]- General Clark walked the campus like a retired deity and ignored the general run of cadets.

- p. 5

- The Citadel cherishes the belief that the more hardship endured by the young man, the higher the quality of the person who graduates from the system. The Citadel devised a formula years ago to improve the quality of men who walked through her gates. The formula begins with the plebe system. One thing is certain. The plebe system is calculated to be, and generally succeeds in being, a nine month journey through hell. The freshman is beaten, harassed, ridiculed, and humiliated by the upperclassmen who concur and believe in the traditions of the school. Under the pressure of this system, the freshman, in theory, becomes hardened to the savage hardships of the world. Life is tough, the system says, and we are going to make life so tough for you this year that when your marriage dissolves, your child dies unexpectedly, or your platoon is decimated in a surprise attack, you can never say The Citadel didn't prepare you for the worst in life.

- p. 6-7

- Cadets are people. Behind the gray suits, beneath the Pom-pom and Shako and above the miraculously polished shoes, blood flows through veins and arteries, hearts thump in a regular pattern, stomachs digest food, and kidneys collect waste. Each cadet is unique, a functioning unit of his own, a distinct and separate integer from anyone else. Part of the irony of military schools stems from the fact that everyone in these schools is expected to act precisely the same way, register the same feelings, and respond in the same prescribed manner. The school erects a rigid structure of rules from which there can be no deviation. The path has already been carved through the forest and all the student must do is follow it, glancing neither to the right nor left, and making goddamn sure he participates in no exploration into the uncharted territory around him. A flaw exists in this system. If every person is, indeed, different from every other person, then he will respond to rules, regulations, people, situations, orders, commands, and entreaties in a way entirely depending on his own individual experiences. The cadet who is spawned in a family that stresses discipline will probably have less difficulty in adjusting than the one who comes from a broken home, or whose father is an alcoholic, or whose home is shattered by cruel arguments between the parents. Yet no rule encompasses enough flexibility to offer a break to a boy who is the product of one of these homes.

- p. 10

- Graduation was nice. General Clark liked it. The Board of Visitors liked it. Moms and Dads liked it. And the Cadets hated it, for without a doubt it ranked as the most boring event of the year. Thus it was in 1964 that the Clarey twins pulled the graduation classic. When Colonel Hoy called the name of the first twin, instead of walking directly to General Clark to receive his diploma, he headed for the line of visiting dignitaries, generals, and members of the Board of Visitors who sat in a solemn semi-circle around the stage. He shook hands with the first startled general, then proceeded to shake hands and exchange pleasantries with every one on the stage. He did this so quickly that it took several moments for the whole act to catch on. When it finally did, the Corps went wild. General Clark, looking like he had just learned the Allies had surrendered to Germany, stood dumbfounded with Clarey number one's diploma hanging loosely from his hand; then Clarey number two started down the line, repeating the virtuoso performance of Clarey number one, as the Corps whooped and shouted their approval. The first Clarey grabbed his diploma from Clark and pumped his hand vigorously up and down. Meanwhile, his brother was breezing through the hand-shaking exercise. As both of them left the stage, they raised their diplomas above their heads and shook them like war tomahawks at the wildly applauding audience. No graduation is remembered so well.

- p. 33

- One problem the museum has always had in the eyes of some cadets is its worship of General Mark Clark. One whole room of the museum is dedicated to the propagation of Clark's exploits through two wars. The room itself is dark, an inner sanctum lit with tabernacle lights, and smoking with a kind of mystical incense which seems to compliment the godly aura of the man himself... Statues of Clark, pictures of Clark, letters from Clark, letters to Clark, speeches by Clark, and a seemingly endless amount of Clark memorabilia helps make the museum a monument to his career. If any pictures were available of Clark walking on water or changing wine into water, they would be dutifully placed in the museum by people who suffer guilt feelings that The Citadel has never produced an international figure of its own.

- p. 95

The Water is Wide (1972)

[edit]- The Southern school superintendent is a kind of remote deity who breathes the purer air of Mount Parnassus. The teachers see him only on those august occasions when they need to be reminded of the nobility of their calling. The powers of a superintendent are considerable. He hires and fires, manipulates the board of education, handles a staggering amount of money, and maintains the precarious existence of the status quo.

- p. 11

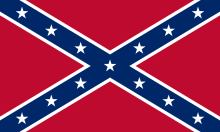

- It was so easy before. Segregation was such an easy thing. The dichotomy of color in the schools made administration so pleasant... It was once so much nicer. They controlled black principals who shuffled properly, who played the role of downcast eyes and easy niggers, and who sold their own children and brothers on the trading block of their own security. These men helped grease the path of the South's Benningtons and Piedmonts as they slid through the years. The important things were order, control, obedience, and smooth sailing. As long as a school looked good and children behaved properly and troublemakers were rooted out, the system held up and perpetuated itself. As long as blacks and whites remained apart- with the whites singing "Dixie" and the blacks singing "Lift Every Voice and Sing," with the whites getting scholarships and the blacks getting jobs picking cotton and tomatoes, with the whites going to college and the blacks eating moon pies and drinking Doctor Pepper- the Piedmonts and Benningtons could weather any storm or surmount any threat. All of this ended with the coming of integration to the South.

- p. 311

- During the entire period of my banishment and trial, I wanted to tell Piedmont and Bennington that what was happening between us was not confined to Beaufort, South Carolina. I wanted to tell them about the river that was rising quickly, flooding the marshes and threatening the dry land. I wanted them to know that their day was ending. When I saw them at the trial, I knew that they were the soldiers of the rear guard, captains of a doomed army retreating through the snow and praying that the quick, dark wolves, waiting in the cold, would come no closer. They were old men and could not accept the new sun rising out of the strange waters. The world was very different now.

- p. 311-312

- The South of humanity and goodness is slowly rising out of the fallen temple of hatred and white man's nationalism. The town retains her die-hards and nigger-haters and always will. Yet they grow older and crankier with each passing day. When Beaufort digs another four hundred holes in her plentiful grave-yards, deposits there the rouged and elderly corpses, and covers them with the sandy, lowcountry soil, then another whole army of the Old South will be silenced and not heard from again. The religion of the Confederacy and apartheid will one day be subdued by the passage of years. The land will be the final arbiter of human conflict; no matter how intense the conflict, the victory of earth and grave will be complete.

- p. 313

1980s

[edit]The Lords of Discipline (1980)

[edit]- I wear the ring.

- p. 1

- I have never had to look up a definition of honor. I knew instinctively what it was. It is something I had the day I was born, and I never had to question where it came from or by what right it was mine. If I was stripped of my honor, I would choose death as certainly and unemotionally as I clean my shoes in the morning. Honor is the presence of God in man.

- p. 46. Said by character General Bentley Durrell.

- "I didn't get the point", said Pig. "That's because you've got four pounds of provolone where most people got brains!", Mark shouted, shaking his fist. "This is college, you dumb bastard. This is a place where you're supposed to argue and learn and get pissed off. You don't go around choking your buddies just because they don't happen to believe what you believe."

- p. 88

- Matt Ledbetter cleared his throat and spoke to me in a voice trembling with emotion. "Will, that freshman doesn't belong in this school. We've got to run him out of here. We can't help it if he cries. He cries every time we look at him. He simply doesn't belong here. It'll be better for him and the other knobs when he goes." "Last year, you were a freshman, Matt. This year you're God." "He doesn't belong here, Will. It's our duty to run him out. We owe it to the Institute. We owe it to the line." "Your duty?" I asked him. "Our duty," Matt replied.

- p. 96

- It was dangerous to have a sadist in the barracks, especially one who justified his excesses by religiously invoking the sacrosanct authority of the plebe system. The system contained its own high quotient of natural cruelty, and there was a very thin line between devotion to duty, that is, being serious about the plebe system, which was an exemplary virtue in the barracks, and genuine sadism, which was not. But I had noticed that in the actual hierarchy of values at the Institute, the sadist like Snipes rated higher than someone who took no interest in the freshmen and entertained no belief in the system at all. In the Law of the Corps it was better to carry your beliefs to an extreme than to be faithless. For the majority of the Corps, the only sin of the sadist was that he believed in the system too passionately and applied his belief with an overabundant zeal. Because of this, the barracks at all times provided a safe regency for the sadist and almost all of them earned rank. My sin was harder to figure. I did not participate at all in the rituals of the plebe system. Cruelty was easier to forgive than apostasy.

- p. 96

- I developed The Great Teacher theory late in my freshman year. It was a cornerstone of the theory that great teachers had great personalities and that the greatest teachers had outrageous personalities. I did not like decorum or rectitude in a classroom; I preferred a highly oxygenated atmosphere, a climate of intemperance, rhetoric, and feverish melodrama. And I wanted my teachers to make me smart. A great teacher is my adversary, my conqueror, commissioned to chastise me. He leaves me tame and grateful for the new language he has purloined from other kings whose granaries are filled and whose libraries are famous. He tells me that teaching is the art of theft; knowing what to steal and from whom. Bad teachers do not touch me; the great ones never leave me. They ride with me during all my days, and I pass on to others what they have imparted to me. I exchange their handy gifts with strangers on trains, and I pretend the gifts are mine. I steal from the great teachers. And the truly wonderful thing about them is that they would applaud my theft, laugh at the thought of it, realizing that they had taught me their larcenous skills well.

- p. 271

- It is a nation of contradictions, sir. Consider this: Ireland is an island nation that has never developed a navy; a music-loving people who have produced only those harmless lilting ditties as their musical legacy; a bellicose people who have never known the sweet savor of victory in a single war; a Catholic country that has never produced a single doctor of the Church; a magnificently beautiful country, a country to inspire artists, but a country not yet immortalized in art; a philosophic people yet to produce a single philosopher of note; a sensual people who have never mastered the art of preparing food.

- p 274. Said by character Colonel Edward T. Reynolds.

- The drums ceased and the parade ground was as silent as an inland sea. At the other end of the parade ground, I heard Gauldin Grace's harsh, overextended voice screaming out the findings of the honor court. "Gentlemen, the honor court has met tonight and has found Pignetti, D.A., Company R, guilty of the honor code violation of stealing. His name will never be spoken by any man from Carolina Military Institute. He will never return to the campus so long as he may live. His name and memory are anathema to anyone who aspires to wear the ring. Let him go from us and never be heard from again. Let him begin the Walk of Shame."

- p. 439

- When the ceremony was over, I found The Bear and handed him my diploma along with a ballpoint pen. "What's this for, lamb?" "I want you to sign it, Colonel. I want you to make it official," I answered. "I want the name of a man I can respect on my diploma, Colonel." He handed me back the diploma without signing it. "There already is, Bubba," he answered. "There already is." And he pointed to my name.

- p. 498

The Prince of Tides (1986)

[edit]- My wound is geography. It is also my anchorage, my port of call.

- p. 1

- I would take you to the marsh on a spring day, flush the great blue heron from its silent occupation. Scatter marsh hens as we sink to our knees in mud, open an oyster with a pocket knife, feed it to you from the shell and say, "There. That taste. That's the taste of my childhood." I would say, "Breathe deeply," and you would breathe and remember that smell for the rest of your life. That bold aroma of the tidal marsh, exquisite and sensual, the smell of the South in heat, a smell like new milk and spilled wine, all perfumed with sea water.

- p. 2

1990s

[edit]Eulogy for a Fighter Pilot (1998)

[edit]Eulogy delivered by Conroy at the funeral of his father, Colonel Don Conroy, USMC, in 1998.[1]

- The children of fighter pilots tell different stories than other kids do. None of our fathers can write a will or sell a life insurance policy or fill out a prescription or administer a flu shot or explain what a poet meant. We tell of fathers who land on aircraft carriers at pitch-black night with the wind howling out of the China Sea. Our fathers wiped out aircraft batteries in the Philippines and set Japanese soldiers on fire when they made the mistake of trying to overwhelm our troops on the ground. Your Dads ran the barber shops and worked at the post office and delivered the packages on time and sold the cars, while our Dads were blowing up fuel depots near Seoul, were providing extraordinarily courageous close air support to the beleaguered Marines at the Chosin Reservoir, and who once turned the Naktong River red with blood of a retreating North Korean battalion. We tell of men who made widows of the wives of our nations' enemies and who made orphans out of all their children. You don't like war or violence? Or napalm? Or rockets? Or cannons or death rained down from the sky? Then let's talk about your fathers, not ours. When we talk about the aviators who raised us and the Marines who loved us, we can look you in the eye and say "you would not like to have been American's enemies when our fathers passed overhead". We were raised by the men who made the United States of America the safest country on earth in the bloodiest century in all recorded history. Our fathers made sacred those strange, singing names of battlefields across the Pacific: Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, the Chosin Reservoir, Khe Sanh and a thousand more. We grew up attending the funerals of Marines slain in these battles. Your fathers made communities like Beaufort decent and prosperous and functional; our fathers made the world safe for democracy.

- Donald Conroy is the only person I have ever known whose self-esteem was absolutely unassailable. There was not one thing about himself that my father did not like, nor was there one thing about himself that he would change. He simply adored the man he was and walked with perfect confidence through every encounter in his life. Dad wished everyone could be just like him. His stubbornness was an art form. The Great Santini did what he did, when he wanted to do it, and woe to the man who got in his way. Once I introduced my father before he gave a speech to an Atlanta audience. I said at the end of the introduction, "My father decided to go into the Marine Corps on the day he discovered his IQ was the temperature of this room". My father rose to the podium, stared down at the audience, and said without skipping a beat, "My God, it's hot in here! It must be at least 180 degrees".

- Here is how my father appeared to me as a boy. He came from a race of giants and demi-gods from a mythical land known as Chicago. He married the most beautiful girl ever to come crawling out of the poor and lowborn south, and there were times when I thought we were being raised by Zeus and Athena. After Happy Hour my father would drive his car home at a hundred miles an hour to see his wife and seven children. He would get out of his car, a strapping flight jacketed matinee idol, and walk toward his house, his knuckles dragging along the ground, his shoes stepping on and killing small animals in his slouching amble toward the home place. My sister, Carol, stationed at the door, would call out, "Godzilla's home!" and we seven children would scamper toward the door to watch his entry. The door would be flung open and the strongest Marine aviator on earth would shout, "Stand by for a fighter pilot!" He would then line his seven kids up against the wall and say, "Who's the greatest of them all?" "You are, O Great Santini, you are." "Who knows all, sees all, and hears all?" "You do, O Great Santini, you do." We were not in the middle of a normal childhood, yet none of us were sure since it was the only childhood we would ever have. For all we knew other men were coming home and shouting to their families, "Stand by for a pharmacist," or "Stand by for a chiropractor".

- When he flew back toward the carrier that day, he received a call from an Army Colonel on the ground who had witnessed the rout of the North Koreans across the river. "Could you go pass over the troops fifty miles south of here? They've been catching hell for a week or more. It'd do them good to know you flyboys are around." He flew those fifty miles and came over a mountain and saw a thousand troops lumbered down in foxholes. He and Bill Lundin went in low so these troops could read the insignias and know the American aviators had entered the fray. My father said, "Thousands of guys came screaming out of their foxholes, son. It sounded like a world series game. I got goose pimples in the cockpit. Get goose pimples telling it forty-eight years later. I dipped my wings, waved to the guys. The roar they let out. I hear it now. I hear it now."

Letter to his readers (1998)

[edit]Public letter from Conroy to readers and fans in the aftermath of the death of his father, Colonel Don Conroy, USMC, in 1998.[2]

- Don Conroy was larger than life and there was never a room he entered that he left without making his mark. At some point in his life, he passed from being merely memorably to being legendary.

- In the thirty-three years he was in the Marine Corps, Col. Conroy concentrated on the task of defending his country and he did so, exceedingly well. In the next twenty-four years left to him, he put all his efforts into the art of being a terrific father, a loving uncle, a brother of great substance, a beloved grandfather, and a friend to thousands. Out of uniform, the Colonel let his genius for humor flourish. Always in motion he made his rounds in Atlanta each day and no one besides himself knew how many stops he put in during a given day. He was like a bee going from flower to flower, pollinating his world with his generous gift for friendships.

- Don Conroy died with exemplary courage, as one would expect. He never complained about pain or whimpered or cried out. His death was stoical and quiet. He never quit fighting, never surrendered, and never gave up. He died like a king. He died like The Great Santini. I thank you with all my heart.

2000s

[edit]Eulogy for "The Boo" (May 3, 2006)

[edit]Eulogy delivered by Conroy at the 2006 funeral of former Assistant Commandant of Cadets at The Citadel and Citadel graduate Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Nugent Courvousie, U.S. Army, Ret., nicknamed "The Boo" by cadets.[3]

- Here is what The Boo loved more than The Citadel - nothing, nothing on this Earth. The sun rose on Lesesne Gate and it set on the marshes of the Ashley River and its main job was to keep the parade grounds green. He once told me that a cadet was nothing but a bum, like you, Conroy. But a Corps of Cadets was the most beautiful thing in the world. In World War II, he led an artillery unit during the Battle of the Bulge and he once told me, 'The Germans hated to see me and my boys catch em in the open.' It is my own personal belief that The Boo's own voice was more frightening to the Germans than the artillery fire he was directing toward them.

- You have never been blessed out or bawled out or chewed out unless you got it from The Boo in his prime. Did I say he was five times louder than God? I'm sorry if that sounds sacrilegious and it certainly is not true. The Boo was at least ten times louder than God and I was scared of him my entire cadet career.

- 'There was only one cadet I ever really hated. Just one name I can think of,' The Boo said. 'That'll make an interesting story for the book, Colonel. Who is the jerk?' I asked. 'It was you, Conroy. Just you. There was something about you that I hated when you first walked into fourth battalion, you worthless bum.'

- When I was writing 'The Lords of Discipline,' I went to The Boo for help. 'What makes The Citadel different from all other schools? What makes it different, special and unique? Why do I think it is the best college in the world when I hated it when I was here, Boo? Help me with this.' The Boo held up his hand and said, 'It's the ring, Bubba. Always remember that. The ring, the ring, the ring.' I thought about it for a moment then wrote the words, 'I wear the ring.' 'How about this for a first line?' 'Perfect, Bubba, just perfect.'

2010s

[edit]A Low Country Heart (2016)

[edit]- Hello, out there.

This is the first letter I've ever written for a website, modern times seem to require it of all human beings. This website was produced by Mihai (Michael) Radulescu, my agent Marly Rusoff's partner, who spent a couple of hours explaining its intricacies and its cunninng store of useless data concerning my own squirrelly life. I'm the only writer I know whose website bears the artistic mark of a native-born Romanian. The Internet remains a mystery to me as vast and untouchable as any ocean. I don't understand it but the wizards and snake handlers who control me tell me that all this is part of the inexplicable strangeness of the world we now inhabit.

My health went south on me this spring. In the middle of May, I began internally bleeding. I took this as a very bad sign that did not bode well for a frisky old age. My wife, Cassandra, drove me to the emergency room in Beaufort where my doctor, Lucius Lafitte, met me and got me to the Medical University of South Carolina. All the nurses and doctors there were spectacular. They saved my life.- 3 August 2009

- p. 15-16

- Everything that was wrong with me that night was my fault. I had tantalized the fates by embracing that life-defying trifecta: overeating, overdrinking, and lack of exercise. I'm trying to develop the appetite of a parakeet, drink nothing stronger than Clamato juice, and try to do aerobics in a Fripp Island pool as often as I can. When I enter the pool I look as though I'm trying out for a part as Moby-Dick. It's not a pretty sight.

- 3 August 2009

- p. 16

- The tour for South of Broad began at my house at Fripp this past week. The tour is abbreviated because of my health, which I regret. I always liked meeting and talking to you guys on the road, but that was a time before airline travel became an American nightmare. I'll go by car on most of the signings, and we'll see how it goes. I'm alone in a room for most of my life, writing, and I love when readers bring me news of the outside world. That part of my life might be coming to an end, and nothing fills me with more regret. To have attracted readers is the most magical part of my writing life. I was not expecting you to show up when I wrote my first books. It took me by surprise. It filled me with gratitude. It still does.

- 3 August 2009

- p. 16-17

- Yesterday, August 2, I took my agents to Charleston for a tour of the city. A young publicist from Random House, Elizabeth Johnson, went with us. She married a Marine Corps fighter pilot and they are stationed at the Marine Corps Air Station, where he is in training before shipping out to one of the war zones. I've always taken a childish joy in showing off Charleston to strangers in the city. Charleston never lets me down, but this time my tour of the city had an unusual twist. I showed them Charleston through the eyes of the narrator of South of Broad, Leo King. I followed Leo's paper route through the old part of the city, showed them the high points and low points of Leo's career as a child. I showed them the distinguished line of mansions that grace the jacket of the book. To me it composes the prettiest formation of houses in the book. We toured The Citadel and I pointed out the places I had lived when I was pretending to be a cadet, I owe The Citadel more than I can express in words. That day, The Citadel was beautiful in sunlight, and Charleston strutted in the beauty of all its strange elixirs. For lunch we ate at Magnolias; all four of us ordered seafood over grits; lobster, shrimp, and scallops with a lobster sauce. It was as good as food can get. Later I returned home. I remembered dozens of things I forgot to tell them. My new book has changed the way I see and present Charleston, and nothing makes me happier.

- 3 August 2009

- p. 17-18

- I close the first letter with relief and some anxiety. They tell me I should do this every now and then. In some ways it seems like a nightmare for someone who never learned to type, in other ways an opening to the light.

Great love out there...- 3 August 2009

- p. 19

- You know how my story as a teacher ended. The white boys rose up and got rid of this hotheaded white boy. I never taught again. The white boys won, or so they thought. That superintendent and that school board drove me out of a job and eventually out of Beaufort. But to you, the people of Penn Center, whose ancestors survived the grueling Middle Passage and the heat of cotton fields and the whips of overseers- rejoice with me. I'm living proof that Penn Center can change a white boy's life. You changed me utterly and I'm forever grateful to you. Yes, I was fired, humiliated, and run out of town because I believed what Martin Luther King believed. Yes, they got me good, Penn Center, but on this joyous night, let me brag to you at last: Didn't I get those sorry sons of bitches back? Thank you very much.

- 2010 speech at Penn Center on Saint Helena Island, South Carolina

- p. 34

- Hey, out there,

About the war between me and technology: it appears that technology is rolling over me like a blitzkrieg. I'm a victim of all its barbarisms. I still can't type, which makes my emails seem composed by a highlands baboon. Once or twice a week, I check my e-mail, whether I need to or not. I understand that most human beings check theirs with more frequency. Twitter is an unknown factor in my life and I've never seen Facebook, even though I'm told I have a presence on both of these entities. People give me looks of pity and ask me why I want to wallow in my disconnection from a very connected world. It is simple. The world seems way too connected for me now. It seems to be ruining the lives of teenagers and bringing out the bestial cruelty in those who can hide their vileness under the mask of some idiotic pseudonym. I like to sit alone and think about things. Solitude is as precious as coin silver and it takes labor to attain it. I can be frivolous without Twitter and Facebook. I turned sixty-five this year and I take old age seriously. There's work to be done.- October 2010

- p. 36

- For those readers who don't know, The Boo was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Nugent Courvoisie, the assistant commandant of cadets at The Citadel and the subject of my first book, The Boo. I often tell people The Boo is "the worst book ever written by an American," and I wish I'd written it better. But the evening made me think a lot about The Boo, who is buried near my parents in the Beaufort National Cemetery. I was scared of him at The Citadel, but he was a source of humanity and justice, and the most beloved man on campus during his brief time among the cadets. I went looking for the presentation copy of The Boo he had given me in 1970. I had never opened it that I could remember, and I wanted to see if he had signed it. When I opened it, I found these eight words written to me forty-one years ago: "To the lamb who made me, The Boo." These words made my whole writing career worthwhile.

And I have begun thinking of that life as miraculous and lucky. How could a man I had dreaded as my commandant and who tried twice to get me kicked out of college become the subject of the first book I would write? How could the young kid I was then become one of the closest friends The Boo would ever make? Who could have predicted that The Boo would be hired as the mighty advisor for the filming of The Lords of Discipline in England? After his long humiliation and exile by The Citadel, who would have predicted that he and I would both be honored by a full-dress parade and honorary degrees as we stood shoulder-to-shoulder on the same parade ground we had marched on as boys? Who coud have foreseen the day I would deliver his eulogy at the Summerall Chapel, or that I would give a speech on the night they named the dining room in the new Alumni Hall after him? Not me. Not once. Not ever.- 6 November 2011

- p. 48

- I am lucky to get to know a man as fine as Charlie Gibson. America is lucky to have him delivering the news.

- 27 October 2013

- p. 86

Quotes about Conroy

[edit]

- He left the same message every few months, the same message, word for word.

"Bragg? This is Conroy. It is now obvious that it is up to me to keep this dying friendship alive. You do not write. You do not call. But I am willing to carry this burden by all by myself. It is a tragedy. Ours could have been a father-son relationship, but you rejected that. And now it is all up to me, to keep this dying [bleep, bleep, bleepity, bleeping] friendship from fading away..." And then there would be a second or two of silence, before: "I love you, son." That part always sounded real.

I would always call back, immediately, but the voice mail just told me it was full, always full. I would learn, over decades, that it was full because I was not the only writer or friend he had adopted, or even the only one he left that same message of mock disappointment and feigned regret. But now and then I would actually be there when he called, and we would talk an hour or two about writers and language and why I should love my mother, and he would always, always tell me he had read my latest book, and how he was proud of me. Then he would tell me how he did not mind that I had neglected our friendship and that his broad shoulders could carry the weight of my indifference, and the phone would go dead.

My God, I will miss that.- Rick Bragg, "An Homage to a Southern Literary Giant and a Prince of a Guy", Southern Living, May 2016, reprinted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 283-284

- As he left, I knew I was now only the second most popular writer in our home; The Water is Wide is my mother's favorite book. Because of him, we see the good in Santini, and know that any man, no matter how wounded or damaged, can be a prince of tides. We will miss the words he still had to write. We will miss a damn sight more than that.

- Rick Bragg, "An Homage to a Southern Literary Giant and a Prince of a Guy", Southern Living, May 2016, reprinted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 286

- To the lamb that made me. The Boo.

- Thomas Nugent Courvousie, a.k.a. "The Boo," Assistant Commandant of Cadets at The Citadel from 1961 to 1982, inscribed in the presentation copy of The Boo, Conroy's first book, at the book's launch party at Conroy's mother's house on East Street in Beaufort, South Carolina in 1970. As quoted by Conroy himself in an October 2010 online letter to readers, reprinted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 37

- Pat's book signings told me everything I ever needed to know about him. He refused to take even the quickest of breaks. The staff and I would plead with him, but to no avail. I'd insist the staff have food for him, which they probably loved me for, since they'd end up eating it. He certainly didn't. He would sign until the last person left, even if it was well after midnight. He greeted everyone as though he were running for mayor. He was known for shaking off the efforts of his publicist to hurry the line along, or to stop anyone from bringing more than one book to be signed. "Bring all you have!" Pat would tell his readers jovially, much to the chagrin of the poor publisher's representatives who had been sent to make sure everything went smoothly. I'd see them glare daggers at him at first, but learned quickly to quell my alarm. In no time, I knew, the silver-tongued devil would have them eating out of his hand. And without fail, he always did. Despite the long, exhausting hours and doubtless unpaid overtime Pat's signings cost the staff, it was a sheer pleasure to be with him when he arrived at a bookstore. He was always greeted like visiting royalty, and knew each of the staff by name. He asked after their families, and if they'd ever gotten around to writing the book they had told him about, the last time he was in. Never mind that it had been many years since his last signing there. He remembered everyone.

- Cassandra King, author and Conroy's wife from May 1998 to his passing in March 2016, in "Introduction", A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 6-7

- But more than anything else, Pat's signings were lovefests between him and his readers, and they flocked to him. He made sure their long wait was worth it. Once they got to his table, he'd hold out his hand ans say, "Hi, I'm Pat Conroy. Tell me who you are." In no time, he had pried their stories from them, just as he'd done with me the night we met. Devoted readers would burst into tears upon meeting him, then end up blurting out their innermost secrets, not caring how long they held up the line. It was another thing I observed with amusement, the disgruntled moans and groans of those in line when someone was taking up what appeared to be way too much of Mr. Conroy's time. What was wrong with the staff, that they allowed such a thing to happen? Didn't that fancy New York publicist know he/she was supposed to be herding the crowd along and not just standing there mesmerized? Couldn't someone do something? They would fume and pout until their time came, and then- like magic- it would all disappear. I would watch them melt under Pat's twinkly-eyed gaze, his disarming smile and outstretched hand. Next thing you knew, they too would be leaning over the table, telling him in a low breathless voice a story they'd never, ever told anyone before. No wonder he never ran out of material.

- Cassandra King, "Introduction", A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 7-8

- Tragically, Pat Conroy ran out of time before he ran out of material, and it breaks my heart to think of the stories he did not live to tell. He and I talked often of Time's winged chariot drawing new, and how swiftly it all goes by. Although Pat feared little, one fear haunted him: that he'd run out of time before he could finish the books he still had in him. It was almost a premonition. He was a man who loved the written word beyond all measure, and who believed that each of us has at least one great story to tell. He would grab hold of someone- stranger or friend, it didn't matter- and he wouldn't let go until he pried that story out. Then his eyes would blaze that dazzling Irish blue and a smile would transform him. If the story was good enough to capture his imagination, he couldn't wait to write it down. Whether it was about a white porpoise or a caged tiger or a lost ancestor who sewed coins into the hem of a skirt to buy her freedom, his pen would bring it to life, make it as real to the rest of us as it was to him on hearing it. He would take your story and make it large and glorious and unforgettable. He would make it immortal.

- Cassandra King, "Introduction", A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 8-9

- Donald Patrick Conroy, born on October 26, 1945, was the best storyteller of our time- very possibly any time. We will never forget Donald Patrick Conroy. He came to live in South Carolina on orders of the United States Marine Corps. In 1961, his father, Colonel Donald Conroy, a Marine aviator who went by the nickname of the Great Santini- perhaps you've heard of him- received orders to report to the air station in Beaufort, South Carolina. Pat was sixteen years old and received this news with dread. He had been to ten schools in eleven years and Beaufort High School would become his third high school.

- Alex Sanders, eulogy for Pat Conroy given on 8 March 2016 at St. Peter's Catholic Church in Beaufort, South Carolina, as quoted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 288

- His was a turbulent personality, a complex mixture of joy and despair, but through it all, great love. He loved books and independent bookstores, especially the Old New York Bookshop. Imagine that. He loved his friends, his brothers and sisters, his children and stepchildren, his grandchildren, his legion of readers, who hung on his every word and were enchanted by his characters, the atmosphere of the South Carolina Lowcountry, and his stories- always his stories. But he loved no one more than Sandra, his steadfast wife, Cassandra King. She smoothed out the rough places for him and calmed the turbulence of his life. She loved him unconditionally, as he loved her. She brought him peace at last.

- Alex Sanders, eulogy for Pat Conroy given on 8 March 2016 at St. Peter's Catholic Church in Beaufort, South Carolina, as quoted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 290-291

- Pat Conroy may have come to live among us involuntarily, but he stayed among us by choice and enriched us all for more than fifty years. Many of us saw ourselves reflected in his published words. Some of us he entertained grandly. Others of us he outraged greatly. To all of us, he gave a rare gift. He came to us from afar, like Faulkner and like Wolfe. But I respectfully suggest, in ways more real and more loving than either of them, that he gave to us the opportunity, in the phrase of Burns, "to see ourselves as others see us." For this alone, we should be forever grateful to Pat Conroy, our very own prince of tides. "Good-night, sweet prince. May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest." Hamlet, Act V, Scene 2.

- Alex Sanders, eulogy for Pat Conroy given on 8 March 2016 at St. Peter's Catholic Church in Beaufort, South Carolina, as quoted in A Low Country Heart (2016) by Pat Conroy, New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, hardcover first edition, p. 291