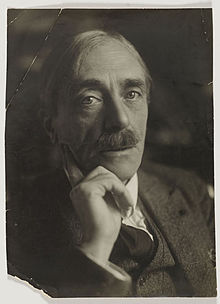

Paul Valéry

Ambroise-Paul-Toussaint-Jules Valéry (30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French author and Symbolist poet. His interests were sufficiently broad that he can be classified as a polymath. In addition to his fiction (poetry, drama, and dialogues), he also wrote many essays and aphorisms on art, history, letters, music, and current events.

Quotes

[edit]

Introduction to the Method of Leonardo da Vinci (1895)

[edit]- Le mal de prendre une hypallage pour une découverte, une métaphore pour une démonstration, un vomissement de mots pour un torrent de connaissances capitales, et soi-même pour un oracle, ce mal naît avec nous.

- Collect all the facts that can be collected about the life of Racine and you will never learn from them the art of his verse. All criticism is dominated by the outworn theory that the man is the cause of the work as in the eyes of the law the criminal is the cause of the crime. Far rather are they both the effects.

Writing at the Yalu River (1895)

[edit]- Vous n’avez ni la patience qui tisse les longues vies, ni le sentiment de l’irrégularité, ni le sens de la place la plus exquise d’une chose, … « L’intelligence, pour vous, n’est pas une chose comme les autres. […] vous l’adorez comme une bête prépondérante. […] Un particulier qu’elle enivre, compare sa pensée aux décisions des lois, aux faits eux-mêmes, nés de la foule et de la durée : il confond le rapide changement de son cœur avec la variation imperceptible des formes réelles et des Êtres durables. … C’est par cette loi que l’intelligence méprise les lois... et vous encouragez sa violence ! Vous en êtes fous jusqu’au moment de la peur. Car vos idées sont terribles et vos cœurs faibles. Vos pitiés, vos cruautés sont absurdes, sans calme, comme irrésistibles. Enfin, vous craignez le sang, de plus en plus. Vous craignez le sang et le temps.

- You have neither the patience that weaves long lines nor a feeling for the irregular, nor a sense of the fittest place for a thing … For you intelligence is not one thing among many. You … worship it as if it were an omnipotent beast … a man intoxicated on it believes his own thoughts are legal decision, or facts themselves born of the crowd and time. He confuses his quick changes of heart with the imperceptible variation of real forms and enduring Beings .... You are in love with intelligence, until it frightens you. For your ideas are terrifying and your hearts are faint. Your acts of pity and cruelty are absurd, committed with no calm, as if they were irresistible. Finally, you fear blood more and more. Blood and time.

- Writing at the Yalu River (1895) quoted in Of Time, Passion, and Knowledge: Reflections on the Strategy of Existence (1990) by Julius Thomas Fraser, Part 2, Images in Heaven and on the Earth, Ch. IV, The Roots of Time in the Physical World. Sect. 3 The Living Symmetries of Physics

La Crise de l'Esprit (1919)

[edit]- We civilizations now know ourselves mortal.

delivered as a lecture (late 1927)

[edit]- For the musician, before he has begun his work, all is in readiness so that the operation of his creative spirit may find, right from the start, the appropriate matter and means, without any possibility of error. He will not have to make this matter and means submit to any modification; he need only assemble elements which are clearly defined and ready-made. But in how different a situation is the poet! Before him is ordinary language, this aggregate of means which are not suited to his purpose, not made for him. There have not been physicians to determine the relationships of these means for him; there have not been constructors of scales; no diapason, no metronome, no certitude of this kind. He has nothing but the coarse instrument of the dictionary and the grammar. Moreover, he must address himself not to a special and unique sense like hearing, which the musician bends to his will, and which is, besides, the organ par excellence of expectation and attention; but rather to a general and diffused expectation, and he does so through a language which is a very odd mixture of incoherent stimuli.

- Originally delivered as a lecture (late 1927); Pure Poetry: Notes for a Lecture The Creative Vision (1960)

Littérature (1930)

[edit]- Poetry is simply literature reduced to the essence of its active principle. It is purged of idols of every kind, of realistic illusions, of any conceivable equivocation between the language of "truth" and the language of "creation."

Moralités (1932)

[edit]- Science is feasible when the variables are few and can be enumerated; when their combinations are distinct and clear. We are tending toward the condition of science and aspiring to do it. The artist works out his own formulas; the interest of science lies in the art of making science.

- Science means simply the aggregate of all the recipes that are always successful. All the rest is literature.

Mauvaises Pensées et Autres (1941)

[edit]- An intelligent woman is a woman with whom one can be as stupid as one wants.

- The painter should not paint what he sees, but what will be seen.

- Everything simple is false. Everything complex is unusable.

The Art of Poetry (1958)

[edit]- The very object of art, the principle of its artifice, is precisely to impart the impression of an ideal state in which the man who reaches it will be capable of spontaneously producing, with no effort or hesitation, a magnificent and wonderfully ordered expression of his nature and our destinies.

- Remarks on Poetry in The Art of Poetry (1958)

Monsieur Teste (1919)

[edit]- This character out of my fantasy, whose author I became in the days of my partly literary, partly solitary or . . inward youth, has lived, apparently, since that faded time with a certain life — which his reticence, more than what he said, has persuaded a few readers to attribute to him.

Teste was conceived — in a room where Auguste Comte spent his early years — at a period when I was drunk on my own will and subject to strange excesses of consciousness of my self.

I was suffering from the acute ailment called precision. I tended toward the extreme of the reckless desire to understand, and I searched in myself for the critical points in my powers of attention.- Preface

- La bêtise n’est pas mon fort. J’ai vu beaucoup d’individus ; j’ai visité quelques nations ; j’ai pris ma part d’entreprises diverses sans les aimer ; j’ai mangé presque tous les jours ; j’ai touché à des femmes. Je revois maintenant quelques centaines de visages, deux ou trois grands spectacles, et peut-être la substance de vingt livres. Je n’ai pas retenu le meilleur ni le pire de ces choses : est resté ce qui l’a pu.

- Stupidity is not my strong point. I have seen many persons; I have visited several countries; I have taken part in various enterprises without liking them; I have eaten nearly every day; I have had women. I can now recall a few hundred faces, two or three great spectacles, and the substance of perhaps twenty books. I have not retained the best nor the worst of these things: what could stay with me did.

- Variant translations:

- Stupidity is not my strong suit.

L'Âme et la danse (1921)

[edit]Dance and the Soul, in Paul Valéry, Dialogues (Bollingen Series XLV 4/Princeton University Press, 1989), translated by William McCausland Stewart

- My soul is nothing now but the dream dreamt by matter struggling with itself!

- Eryximachus, p. 27

- But what, Phaedrus, is the contrary of a dream if not some other dream?… A dream of vigilance and tension dreamt by Reason herself!—And what would such a Reason dream?—If a Reason were to dream—a Reason hard, erect, eyes armed, mouth closed, as though mistress of her lips—would not the dream she dreamt be what we see now—this world of exact forces and studied illusions?—A dream, a dream, but a dream interpenetrated with symmetries, all order, acts and sequences!

- Socrates, p. 35

- You have experienced nothing that was not both lawful and obscure, and thus conforming perfectly to the human machine. Are we not organized fantasy? And is not our living system functioning incoherency, disorder in action? Do not events, desires, ideas interchange within us in the most necessary and incomprehensible ways?

- Eryximachus to Phaedrus, p. 43

- Reason, sometimes, seems to me to be the faculty our soul possesses of understanding nothing about our body!

- Eryximachus, p. 46

- [T]he soul of love is the invincible difference of lovers, while its subtle matter is the identity of their desires.

- Phaedrus, p. 47

- What are mortals for?—Their business is to know. Know? And what is to know?—It is assuredly: not to be what one is.—And so here are humans raving and thinking, introducing into nature the principle of unlimited error, and myriads of marvels!

- Eryximachus, p. 52

Eupalinos ou l'architecte (1921)

[edit]Eupalinos, or The Architect, in Paul Valéry, Dialogues (Bollingen Series XLV 4/Princeton University Press, 1989), translated by William McCausland Stewart

- I cannot think that there exists more than one Sovereign Good.

- Socrates, p. 81

- To construct oneself, to know oneself—are these two distinct acts or not?

- Socrates, p. 81

- What is most beautiful is of necessity tyrannical.

- Eupalinos quoted by Phaedrus, p. 86

- What is there more mysterious than clarity?… What more capricious than the way in which light and shade are distributed over hours and over men?

- Socrates, p. 107. Ellipsis in original.

- Man can act only because he can ignore.

- Socrates, p. 124

- And do not humans strive in a thousand ways to fill or to break the eternal silence of those infinite spaces that affright them?

- Socrates, p. 125

- Valéry alludes to a famous pensée of Blaise Pascal: 'The eternal silence of these infinite spaces affrights me.' (Pensées, no. 201).

- Man discerns three great things in the All: he finds there his body, he finds there his soul—and then there is the rest of the world. Between these things there is an unceasing commerce, and sometimes even a confusion arises; but always after a certain time has elapsed, these three things come to be clearly distinguished from one another.

- Socrates, p. 128

- It is therefore reasonable to think that the creations of man are made either with a view to his body, and that is the principle we call utility, or with a view to his soul, and that is what he seeks under the name of beauty. But, further, since he who constructs or creates has to deal with the rest of the world and with the movement of nature, which both tend perpetually to dissolve, corrupt or upset what he makes, he must recognize and seek to communicate to his works a third principle, that expresses the resistance he wishes them to offer to their destiny, which is to perish. So he seeks solidity or lastingness.

- Socrates, pp. 128–9

- Nay, who knows, Phaedrus, if the efforts of humans in their search for God, the observances, the prayers they essay, their obstinate will to discover the most efficacious… who knows if mortals will not finally discover a certitude—or an incertitude—stable and in exact conformity with their nature, if not with the very nature of God?

- Socrates, p. 130. Ellipsis in original.

- The greatest liberty is born of the greatest rigor.

- Socrates, p. 131

- Most people in reasoning, dear Phaedrus, use notions that not only are "ready-made," but have actually been made by nobody. No one is responsible for them, and so they serve everyone badly.

- Socrates, p. 137

- Man's deepest glances are those that go out to the void. They converge beyond the All.

- Socrates, p. 141

- Now, of all acts the most complete is that of constructing. A work demands love, meditation, obedience to your finest thought, the invention of laws by your soul, and many other things that it draws miraculously from your own self, which did not suspect that it possessed them. This work proceeds from the most intimate center of your existence, and yet it is distinct from yourself.

- Socrates, p. 145

- But still less should the gold of rich men lazily sleep its heavy sleep in the urns and gloom of treasuries. This so weighty metal, when it becomes the associate of a fancy, assumes the most active virtues of the mind. It has her restless nature. Its essence is to vanish. It changes into all things, without being itself changed. It raises blocks of stone, pierces mountains, diverts rivers, opens the gates of fortresses and the most secret hearts; it enchains men; it dresses, it undresses women with an almost miraculous promptitude. It is truly the most abstract agent that exists, next to thought. But thought exchanges and envelops images only, whereas gold incites and promotes the transmutations of all real things into one another; itself remaining incorruptible, and passing untainted through all hands.

- Socrates, pp. 147–8

Charmes ou poèmes (1922)

[edit]- Ce toit tranquille, où marchent des colombes,

Entre les pins palpite, entre les tombes;

Midi le juste y compose de feux

La mer, la mer, toujours recommencée

O récompense après une pensée

Qu'un long regard sur le calme des dieux!- This quiet roof, where dove-sails saunter by,

Between the pines, the tombs, throbs visibly.

Impartial noon patterns the sea in flame —

That sea forever starting and re-starting.

When thought has had its hour, oh how rewarding

Are the long vistas of celestial calm!- Le Cimetière Marin · Online original and translation as "The Graveyard By The Sea" by C. Day Lewis

- Variant translations:

- The sea, the ever renewing sea!

- This quiet roof, where dove-sails saunter by,

- Quel pur travail de fins éclairs consume

Maint diamant d'imperceptible écume,

Et quelle paix semble se concevoir!

Quand sur l'abîme un soleil se repose,

Ouvrages purs d'une éternelle cause,

Le temps scintille et le songe est savoir.- What grace of light, what pure toil goes to form

The manifold diamond of the elusive foam!

What peace I feel begotten at that source!

When sunlight rests upon a profound sea,

Time's air is sparkling, dream is certainty —

Pure artifice both of an eternal Cause.- As translated by by C. Day Lewis

- What grace of light, what pure toil goes to form

- Beau ciel, vrai ciel, regarde-moi qui change!

Après tant d'orgueil, après tant d'étrange

Oisiveté, mais pleine de pouvoir,

Je m'abandonne à ce brillant espace,

Sur les maisons des morts mon ombre passe

Qui m'apprivoise à son frêle mouvoir.- Beautiful heaven, true heaven, look how I change!

After such arrogance, after so much strange

Idleness — strange, yet full of potency —

I am all open to these shining spaces;

Over the homes of the dead my shadow passes,

Ghosting along — a ghost subduing me.- As translated by by C. Day Lewis

- Beautiful heaven, true heaven, look how I change!

- Ici venu, l'avenir est paresse.

L'insecte net gratte la sécheresse;

Tout est brûlé, défait, reçu dans l'air

A je ne sais quelle sévère essence . . .

La vie est vaste, étant ivre d'absence,

Et l'amertume est douce, et l'esprit clair.- Now present here, the future takes its time.

The brittle insect scrapes at the dry loam;

All is burnt up, used up, drawn up in air

To some ineffably rarefied solution . . .

Life is enlarged, drunk with annihilation,

And bitterness is sweet, and the spirit clear.- As translated by by C. Day Lewis

- Now present here, the future takes its time.

- Allez! Tout fuit! Ma présence est poreuse,

La sainte impatience meurt aussi!- All perishes. A thing of flesh and pore

Am I. Divine impatience also dies.- As translated by by C. Day Lewis

- All perishes. A thing of flesh and pore

- Le vent se lève! . . . il faut tenter de vivre!

L'air immense ouvre et referme mon livre,

La vague en poudre ose jaillir des rocs!

Envolez-vous, pages tout éblouies!

Rompez, vagues! Rompez d'eaux rejouies

Ce toit tranquille où picoraient des focs!- The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!

The huge air opens and shuts my book: the wave

Dares to explode out of the rocks in reeking

Spray. Fly away, my sun-bewildered pages!

Break, waves! Break up with your rejoicing surges

This quiet roof where sails like doves were pecking.- As translated by by C. Day Lewis

- Variant translations:

- The wind is rising ... we must attempt to live.

- The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!

Regards sur le monde actuel [Reflections on the World Today] (1931)

[edit]- The “determinist” swears that if we knew everything we should also be able to deduce and foretell the conduct of every man in every circumstance, and that is obvious enough. But the expression “know everything” means nothing.

- p. 42

- A really free mind is scarcely attached to its opinions. If the mind cannot help giving birth to … emotions and affections which at first appear to be inseparable from them, it reacts against these intimate phenomena it experiences against its will.

- p. 55

- Great things are accomplished by men who are not conscious of the impotence of man. Such insensitiveness is precious.

But we must admit that criminals are not unlike our heroes in this respect.- p. 58

- It is a sign of the times, and not a very good sign, that these days it is necessary—and not only necessary but urgent—to interest minds in the fate of Mind, that is to say, in their own fate.

- p. 156

- Since everything that lives is obliged to expend and receive life, there is an exchange of modifications between the living creature and its environment.

And yet, once that vital necessity is satisfied, our species—a positively strange species—thinks it must create for itself other needs and tasks besides that of preserving life. … Whatever may be the origin or cause of this curious deviation, the human species is engaged in an immense adventure, an adventure whose objective and end it does not know. …

The same senses, the same muscles, the same limbs—more, the same types of signs, the same instruments of exchange, the same languages, the same modes of logic—enter into the most indispensable acts of our lives, as they figure into the most gratuitous. ...

In short, man has not two sets of tools, he has only one, and this one set must serve him for the preservation of his life and his physiological rhythm, and expend itself at other times on illusions and on the labours of our great adventure. ...

The same muscles and nerves produce walking as well as dancing, exactly as our linguistic faculty enables us to express our needs and ideas, while the same words and forms can be combined to produce works of poetry. A single mechanism is employed in both cases for two entirely different purposes.- pp. 158-159

- There is a value called “mind” as there is a value oil, wheat, or gold. … One can invest in that value, one can “follow” it as they say on the stock exchange; one can watch its fluctuations in I know not what price list which is the world’s general opinion of it. … All these rising and falling values constitute the great market of human affairs. And of these the unfortunate value mind does not stop falling.

- p. 161

- The commerce of minds was necessarily the first commerce in the world, … since before bartering things one must barter signs, and it is necessary therefore that signs be instituted.

There is no market or exchange without language. The first instrument of all commerce is language.- p. 166

- Freedom of mind and mind itself have been most fully developed in regions where trade developed at the same time. In all ages, without exception, every intense production of art, ideas, and spiritual values has occurred in some locality where a remarkable degree of economic activity was also manifest.

- pp. 167-168

- I said that to invite minds to concern themselves with Mind and its destiny was a sign and symptom of the times. Would that idea have occurred to me, had not a whole body of impressions been sufficiently significant and powerful to reflect themselves in me, and for that reflection to become action? And that action, which consists of expressing it in your presence, would not perhaps have been accomplished had I not felt that my impressions were those of many other people, that the sensation of a diminution of mind, of a menace to culture, of a twilight of the most pure gods was a sensation which imposed itself with increasing strength on all those who are capable of feeling something in the order of superior values of which we are speaking.

- p. 172

Tel Quel (1943)

[edit]- That which has always been accepted by everyone, everywhere, is almost certain to be false.

- God created man, and finding him not sufficiently alone, gave him a female companion so that he might feel his solitude more acutely.

- The purpose of psychology is to give us a completely different idea of the things we know best.

- Politeness is organized indifference.

- Politics is the art of stopping people from minding their own business.

- Politics is the art of preventing people from taking part in affairs which properly concern them.

Dialogue de l'arbre (1943)

[edit]Dialogue of the Tree, in Paul Valéry, Dialogues (Bollingen Series XLV 4/Princeton University Press, 1989), translated by William McCausland Stewart

- The being filled with wonder is lovely, like a flower.

- Lucretius, p. 163

- In the Beginning was the Fable.

- Tityrus, p. 169, quoting "a philosopher whose name I have forgotten". The philosopher is Valéry himself, who used this phrase at the end of his essay on Poe's Eureka, and elsewhere (Dialogues, textual note on p. 195).

- What's loftiest in the mind can only live through growth.

- Lucretius, p. 171

- Is not to meditate to deepen oneself in Order?

- Lucretius, p. 173

Degas Danse Dessin (1937)

[edit]- Pascal lui-même n'a pas manqué de s'y tromper, qui traita de cet art avec superbe, et le réduisait à la vanité de poursuivre laborieusement la ressemblance de choses dont la vue d'elles-mêmes est sans intérêt, ce qui prouve qu'il ne savait pas regarder, c'est-à-dire oublier les noms des choses que l'on voit.

- Pascal himself did not fail to make a mistake, who treated this art superbly, and reduced it to the vanity of laboriously pursuing the resemblance of things whose sight of themselves is of no interest, which proves that he did not know how to look, that is to say, how to forget the names of the things we see.

- Machine translation from Degas Danse Dessin, 1965 edition, page 246

- Even Pascal was mistaken when he spoke of this art with arrogance, reducing it to the "vanity" of laboriously pursuing a likeness uninteresting in itself. This proves he did not know how to see, meaning, he could not forget the name of what he saw.

- English translation by Helen Burlin, Degas Dance Drawing, 1948, Lear Publishers, pages 63-64

- Pascal himself did not fail to make a mistake, who treated this art superbly, and reduced it to the vanity of laboriously pursuing the resemblance of things whose sight of themselves is of no interest, which proves that he did not know how to look, that is to say, how to forget the names of the things we see.

Collected Works

[edit]- If the state is strong, it crushes us. If it is weak, we perish.

- History and Politics as translated by D. Folliot and J. Mathews (1971)

- A work is never completed except by some accident such as weariness, satisfaction, the need to deliver, or death: for, in relation to who or what is making it, it can only be one stage in a series of inner transformations.

- "Recollection", Collected Works, vol. 1 (1972), as translated by David Paul

- Variant translations:

- A poem is never finished; it's always an accident that puts a stop to it — i.e. gives it to the public.

- As attributed in Susan Ratcliffe, Concise Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (2011), p. 385.

- A poem is never finished; it is only abandoned.

- Widely quoted, this is a paraphrase of Valéry by W. H. Auden in 1965. See W. H. Auden: Collected Poems (2007), ed. Edward Mendelson, "Author's Forewords", p. xxx.

- An artist never finishes a work, he merely abandons it.

- A paraphrase by Aaron Copland in the essay "Creativity in America," published in Copland on Music (1944), p. 53

- In the eyes of those lovers of perfection, a work is never finished — a word that for them has no sense — but abandoned; and this abandonment, whether to the flames or to the public (and which is the result of weariness or an obligation to deliver) is a kind of an accident to them, like the breaking off of a reflection, which fatigue, irritation, or something similar has made worthless.

- Poe is the only impeccable writer. He was never mistaken.

- Letter to writer André Gide, as quoted in The Tell-Tale Heart: The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe (1978) by Julian Symons, Pt. 1, Epilogue