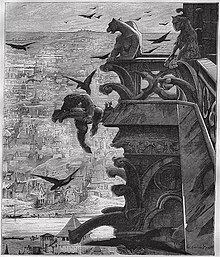

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Appearance

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (French: Notre-Dame de Paris, "Notre-Dame of Paris") is a novel set in 1482 in and around the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, first published in 1831 by the prolific French author Victor Hugo.

Quotes

[edit]- Thousands of good, calm, bourgeois faces thronged the windows, the doors, the dormer windows, the roofs, gazing at the palace, gazing at the populace, and asking nothing more; for many Parisians content themselves with the spectacle of the spectators, and a wall behind which something is going on becomes at once, for us, a very curious thing indeed.

- Book 1, Chapter I, The Grand Hall

- If it could be granted to us, the men of 1830, to mingle in thought with those Parisians of the fifteenth century, and to enter with them, jostled, elbowed, pulled about, into that immense hall of the palace, which was so cramped on that sixth of January, 1482, the spectacle would not be devoid of either interest or charm, and we should have about us only things that were so old that they would seem new.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- Around the hall, along the lofty wall, between the doors, between the windows, between the pillars, the interminable row of all the kings of France, from Pharamond down: the lazy kings, with pendent arms and downcast eyes; the valiant and combative kings, with heads and arms raised boldly heavenward. Then in the long, pointed windows, glass of a thousand hues; at the wide entrances to the hall, rich doors, finely sculptured; and all, the vaults, pillars, walls, jambs, panelling, doors, statues, covered from top to bottom with a splendid blue and gold illumination, which, a trifle tarnished at the epoch when we behold it, had almost entirely disappeared beneath dust and spiders in the year of grace, 1549, when du Breul still admired it from tradition.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- The big furrier, without uttering a word in reply, tried to escape all the eyes riveted upon him from all sides; but he perspired and panted in vain; like a wedge entering the wood, his efforts served only to bury still more deeply in the shoulders of his neighbors, his large, apoplectic face, purple with spite and rage.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- It was, in fact, the rector and all the dignitaries of the university, who were marching in procession in front of the embassy, and at that moment traversing the Place. The students crowded into the window, saluted them as they passed with sarcasms and ironical applause. The rector, who was walking at the head of his company, had to support the first broadside; it was severe.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- Very little to-day remains, thanks to this catastrophe,—thanks, above all, to the successive restorations which have completed what it spared, —very little remains of that first dwelling of the kings of France,—of that elder palace of the Louvre, already so old in the time of Philip the Handsome, that they sought there for the traces of the magnificent buildings erected by King Robert and described by Helgaldus. Nearly everything has disappeared.... Where is the staircase, from which Charles VI. promulgated his edict of pardon? the slab where Marcel cut the throats of Robert de Clermont and the Marshal of Champagne, in the presence of the dauphin? ... and the stone lion, which stood at the door, with lowered head and tail between his legs, like the lions on the throne of Solomon, in the humiliated attitude which befits force in the presence of justice?

- Book 1, Chapter I

- I tell you, sir, that the end of the world has come. No one has ever beheld such outbreaks among the students! It is the accursed inventions of this century that are ruining everything, —artilleries, bombards, and, above all, printing, that other German pest. No more manuscripts, no more books! Printing will kill bookselling. It is the end of the world that is drawing nigh.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- “We must have the mystery instantly,” resumed the student; “or else, my advice is that we should hang the bailiff of the courts, by way of a morality and a comedy.” “Well said,” cried the people, “and let us begin the hanging with his sergeants.” A grand acclamation followed. The four poor fellows began to turn pale, and to exchange glances. The crowd hurled itself towards them, and they already beheld the frail wooden railing, which separated them from it, giving way and bending before the pressure of the throng.

- Book 1, Chapter I

- In the course of time there had been formed a certain peculiarly intimate bond which united the ringer to the church. Separated forever from the world, by the double fatality of his unknown birth and his natural deformity, imprisoned from his infancy in that impassable double circle, the poor wretch had grown used to seeing nothing in this world beyond the religious walls which had received him under their shadow. Notre-Dame had been to him successively, as he grew up and developed, the egg, the nest, the house, the country, the universe.

- Book I, Ch. III, Immanis Pecoris Custos, Immanior Ipse.

- There was certainly a sort of mysterious and pre-existing harmony between this creature and this church. When, still a little fellow, he had dragged himself tortuously and by jerks beneath the shadows of its vaults, he seemed, with his human face and his bestial limbs, the natural reptile of that humid and sombre pavement, upon which the shadow of the Romanesque capitals cast so many strange forms.

- Book I, Ch. III

- The church of Notre-Dame de Paris is still no doubt, a majestic and sublime edifice. But, beautiful as it has been preserved in growing old, it is difficult not to sigh, not to wax indignant, before the numberless degradations and mutilations which time and men have both caused the venerable monument to suffer, without respect for Charlemagne, who laid its first stone, or for Philip Augustus, who laid the last.

On the face of this aged queen of our cathedrals, by the side of a wrinkle, one always finds a scar. Tempus edax, homo edacior; which I should be glad to translate thus: time is blind, man is stupid.- Book III, Ch. I: Notre-Dame

- Opposite the lofty cathedral, reddened by the setting sun, on the stone balcony built above the porch of a rich Gothic house, which formed the angle of the square and the Rue du Parvis, several young girls were laughing and chatting with every sort of grace and mirth. From the length of the veil which fell from their pointed coif, twined with pearls, to their heels, from the fineness of the embroidered chemisette which covered their shoulders and allowed a glimpse, according to the pleasing custom of the time, of the swell of their fair virgin bosoms, from the opulence of their under-petticoats still more precious than their overdress (marvellous refinement), from the gauze, the silk, the velvet, with which all this was composed, and, above all, from the whiteness of their hands, which certified to their leisure and idleness, it was easy to divine they were noble and wealthy heiresses.

- Book VII, Chapter I, The Danger of Confiding One's Secret to a Goat

- The poor dame, very much infatuated with her daughter, like any other silly mother, did not perceive the officer’s lack of enthusiasm, and strove in low tones to call his attention to the infinite grace with which Fleur-de-Lys used her needle or wound her skein.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- Moreover, he was of a fickle disposition, and, must we say it, rather vulgar in taste. Although of very noble birth, he had contracted in his official harness more than one habit of the common trooper. The tavern and its accompaniments pleased him. He was only at his ease amid gross language, military gallantries, facile beauties, and successes yet more easy. He had, nevertheless, received from his family some education and some politeness of manner; but he had been thrown on the world too young, he had been in garrison at too early an age, and every day the polish of a gentleman became more and more effaced by the rough friction of his gendarme’s cross-belt.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- Meanwhile, the dancer remained motionless upon the threshold. Her appearance had produced a singular effect upon these young girls. It is certain that a vague and indistinct desire to please the handsome officer animated them all, that his splendid uniform was the target of all their coquetries, and that from the moment he presented himself, there existed among them a secret, suppressed rivalry, which they hardly acknowledged even to themselves, but which broke forth, none the less, every instant, in their gestures and remarks. Nevertheless, as they were all very nearly equal in beauty, they contended with equal arms, and each could hope for the victory.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- The arrival of the gypsy suddenly destroyed this equilibrium. Her beauty was so rare, that, at the moment when she appeared at the entrance of the apartment, it seemed as though she diffused a sort of light which was peculiar to herself.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- It was, in truth, a spectacle worthy of a more intelligent spectator than Phœbus, to see how these beautiful maidens, with their envenomed and angry tongues, wound, serpent-like, and glided and writhed around the street dancer. They were cruel and graceful; they searched and rummaged maliciously in her poor and silly toilet of spangles and tinsel. There was no end to their laughter, irony, and humiliation. Sarcasms rained down upon the gypsy, and haughty condescension and malevolent looks. One would have thought they were young Roman dames thrusting golden pins into the breast of a beautiful slave. One would have pronounced them elegant greyhounds, circling, with inflated nostrils, round a poor woodland fawn, whom the glance of their master forbade them to devour.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- After all, what was a miserable dancer on the public squares in the presence of these high-born maidens? They seemed to take no heed of her presence, and talked of her aloud, to her face, as of something unclean, abject, and yet, at the same time, passably pretty. The gypsy was not insensible to these pin-pricks. From time to time a flush of shame, a flash of anger inflamed her eyes or her cheeks; with disdain she made that little grimace with which the reader is already familiar, but she remained motionless; she fixed on Phœbus a sad, sweet, resigned look.

- Book VII, Chapter I

- Oh! que ne suis-je de pierre comme toi!

- Oh, why am I not of stone, like you?

- Book IX, Ch. IV. Earthernware and Crystal

- Quand on voulut le détacher du squelette qu'il embrassait, il tomba en poussière.

- When they tried to detach this skeleton from the one it embraced, it crumbled to dust.

- Book XI, Ch. 4

External links

[edit]| This literature-related article is a stub. You can help out with Wikiquote by expanding it! |