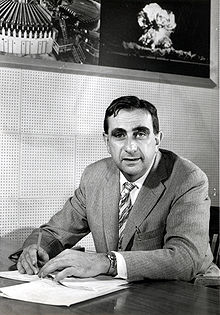

Edward Teller

Appearance

Edward Teller (original Hungarian name Teller Ede) (15 January 1908 – 9 September 2003) was an American nuclear physicist, known as "the father of the hydrogen bomb."

Quotes

[edit]

- It is not even impossible to imagine that the effects of an atomic war fought with greatly perfected weapons and pushed by the utmost determination will endanger the survival of man.

- How Dangerous Are Atomic Weapons?, 1947

- If we stay strong, then I believe we can stabilize the world and have peace based on force. Now, peace based on force is not as good as peace based on agreement, but in the terrible world in which we live, in the world where the Russians have enslaved many millions of human beings, in the world where they have killed men, I think that for the time being the only peace we can have is the peace based on force. Furthermore, I do not think that this peace based on force is, can be, or should be, an ultimate end. Our ultimate end must be precisely what Dr. Pauling says, peace based on agreement, on understanding, on universally agreed and enforced law. I think this is a wonderful idea, but peace based on force buys the necessary time, and in this time we can work for better understanding, for closer collaboration, first with the countries which are closest to us, which we understand better, our allies, the western countries, the NATO countries, which believe in human liberties as we do. Then, as soon as possible, with the rest of the free world, and eventually, I hope, with the whole world, including Russia, even though it may take many years to come.

- I don't want to kill anybody. I am passionately opposed to killing, but I'm even more passionately fond of freedom. The freedom of Dr. Pauling and of myself expressing our opinions freely on any subject, however broad, however far removed of our proper competence, but particularly, to be able to express our opinions in the fields we really know; this would not be possible in Russia.

- Ladies and gentlemen, I am to talk to you about energy in the future. I will start by telling you why I believe that the energy resources of the past must be supplemented. First of all, these energy resources will run short as we use more and more of the fossil fuels. But I would [...] like to mention another reason why we probably have to look for additional fuel supplies. And this, strangely, is the question of contaminating the atmosphere. [....] Whenever you burn conventional fuel, you create carbon dioxide. [....] The carbon dioxide is invisible, it is transparent, you can’t smell it, it is not dangerous to health, so why should one worry about it?

Carbon dioxide has a strange property. It transmits visible light but it absorbs the infrared radiation which is emitted from the earth. Its presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect [....] It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York. All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.- As quoted in Benjamin Franta, "On its 100th birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming", The Guardian, 1 January 2018.

- At present the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by 2 per cent over normal. By 1970, it will be perhaps 4 per cent, by 1980, 8 per cent, by 1990, 16 per cent [about 360 parts per million, by Teller’s accounting], if we keep on with our exponential rise in the use of purely conventional fuels. By that time, there will be a serious additional impediment for the radiation leaving the earth. Our planet will get a little warmer. It is hard to say whether it will be 2 degrees Fahrenheit or only one or 5.

But when the temperature does rise by a few degrees over the whole globe, there is a possibility that the icecaps will start melting and the level of the oceans will begin to rise. Well, I don’t know whether they will cover the Empire State Building or not, but anyone can calculate it by looking at the map and noting that the icecaps over Greenland and over Antarctica are perhaps five thousand feet thick.- As quoted in Benjamin Franta, "On its 100th birthday in 1959, Edward Teller warned the oil industry about global warming", The Guardian, 1 January 2018.

- On May 7, a few weeks after the accident at Three-Mile Island, I was in Washington. I was there to refute some of that propaganda that Ralph Nader, Jane Fonda and their kind are spewing to the news media in their attempt to frighten people away from nuclear power. I am 71 years old, and I was working 20 hours a day. The strain was too much. The next day, I suffered a heart attack. You might say that I was the only one whose health was affected by that reactor near Harrisburg. No, that would be wrong. It was not the reactor. It was Jane Fonda. Reactors are not dangerous.

- 2 page advertisement sponsored by Dresser Industries in the Wall Street Journal (31 July 1979)

- By having simplified what is known, physicists have been led into realms which as yet are anything but simple. That at some time, they, too, will appear as simple consequences of a theory of which no one has yet dreamed is not a statement of fact.

It is a statement of faith.- The Pursuit of Simplicity (1981), p. 72

- The preservation of peace and the improvement of the lot of all people require us to have faith in the rationality of humans. If we have this faith and if we pursue understanding, we have not the promise but at least the possibility of success. We should not be misled by promises. Humanity in all its history has repeatedly escaped disaster by a hair's breadth. Total security has never been available to anyone. To expect it is unrealistic; to imagine that it can exist is to invite disaster. What we do have in our technological capacities is an opportunity to use our inventiveness, our creativity, our wisdom and our understanding of our fellow beings to create a future world that is a little better than the one in which we live today.

- The Pursuit of Simplicity (1981), p. 151

- Variant: Total security has never been available to anyone. To expect it is unrealistic; to imagine that it can exist is to invite disaster. I believe the most important aim for humanity at present is to avoid war, dictatorship, and their awful consequences.

- Better a Shield Than A Sword : Perspectives On Defense And Technology (1987), p. 241

- There's no system foolproof enough to defeat a sufficiently great fool.

- As quoted in "Nuclear Reactions", by Joel Davis in Omni (May 1988)

- A fact is a simple statement that everyone believes. It is innocent, unless found guilty. A hypothesis is a novel suggestion that no one wants to believe. It is guilty, until found effective.

- Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics (1991) by Edward Teller, Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley, Ch. 5, p. 69 footnote

- Two paradoxes are better than one; they may even suggest a solution.

- Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics (1991) by Edward Teller, Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley, Ch. 9, p. 135 footnote

- Physics is, hopefully, simple. Physicists are not.

- Conversations on the Dark Secrets of Physics (1991) by Edward Teller, Wendy Teller and Wilson Talley, Ch. 10, p. 150 footnote

- No, I'm the infamous Edward Teller.

- Response to a nurse, questioning him after a stroke in 1996: "Are you the famous Edward Teller?" — as quoted in Edward Teller and the Development of the Hydrogen Bomb (2001) by John Bankston, p. 9

- We must learn to live with contradictions, because they lead to deeper and more effective understanding.

- "Science and Morality" in Science (1998), Vol. 280, p. 1200

- Religion was not an issue in my family; indeed, it was never discussed. My only religious training came because the Minta required that all students take classes in their respective religions. My family celebrated one holiday, the Day of Atonement, when we all fasted. Yet my father said prayers for his parents on Saturdays and on all the Jewish holidays. The idea of God that I absorbed was that it would be wonderful if He existed: We needed Him desperately but had not seen Him in many thousands of years.

- Memoirs: A Twentieth Century Journey In Science And Politics., (2002) by Edward Teller, Basic Books, p. 32.

- I contributed; Ulam did not. I'm sorry I had to answer it in this abrupt way. Ulam was rightly dissatisfied with an old approach. He came to me with a part of an idea which I already had worked out and difficulty getting people to listen to. He was willing to sign a paper. When it then came to defending that paper and really putting work into it, he refused. He said, "I don't believe in it."

- On the creation of the hydrogen bomb, in "Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café : Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career" by Gary Stix in Scientific American (October 1999), p. 42-43.

- My name is not Strangelove. I don't know about Strangelove. I'm not interested in Strangelove. What else can I say?... Look. Say it three times more, and I throw you out of this office.

- Quoted in "Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café : Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career" by Gary Stix in Scientific American (October 1999), p. 42-43

- The eyes of childhood are magnifying lenses.

- Memoirs : A Twentieth Century Journey in Science and Politics (2001), co-written with Judith Shoolery, p. 5

- When you fight for a desperate cause and have good reasons to fight, you usually win.

- As quoted by Robert C. Martin in Software Development magazine (September 2005), p. 60

- At the end of the war, most people wanted to stop. I didn't. Because here was more knowledge. And in the coming uncertain period, with a dangerous man like Stalin around, and our incomplete knowledge, I felt that more knowledge is necessary. Among the people who knew a great deal about the hydrogen bomb, I was the only advocate of it. And that is, I think, my contribution. Not that I invented it, others would have — and others in the Soviet Union did. But I was the one person who put knowledge, and the availability of knowledge, above everything else.

- On the creation of the hydrogen bomb, in Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie

- There is no case where ignorance should be preferred to knowledge — especially if the knowledge is terrible.

- As quoted in Forbidden Knowledge : From Prometheus to Pornography (1996) by Roger Shattuck, p. 177

- Secrecy in science does not work. Withholding information does more damage to us than to our competitors.

- As quoted in Proceedings of the International Conference on Lasers '87 (1988) edited by F. J. Duarte, p. 1165

- When you come to the end of all the light you know, and it's time to step into the darkness of the unknown, faith is knowing that one of two things shall happen: either you will be given something solid to stand on or you will be taught to fly.

- As quoted in Seven Steps to Starting and Running an Editorial Consulting Business (2002) by Jane M. Frutchey, p. 121

This is misattributed. This is not a quote from Teller. It is a poem by Patrick Overton.

- If we could have ended the war by showing the power of science without killing a single person, all of us would now be happier, more reasonable and much more safe.

- As quoted in "Edward Teller Is Dead at 95; Fierce Architect of H-Bomb", New York Times (Sept. 10, 2003) by Walter Sullivan.

- I hate doubt, yet I am certain that doubt is the only way to approach anything worth believing in.

- As quoted in The Martians of Science : Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006) by István Hargittai, p. 251

- I believe in good. It is an ephemeral and elusive quality. It is the center of my beliefs, but it cannot be strengthened by talking about it.

- As quoted in The Martians of Science : Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006) by István Hargittai, p. 251

- I believe in evil. It is the property of all those who are certain of truth. Despair and fanaticism are only differing manifestations of evil.

- As quoted in The Martians of Science : Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006) by István Hargittai, p. 251

- I believe in excellence. It is a basic need of every human soul. All of us can be excellent, because, fortunately, we are exceedingly diverse in our ambitions and talents.

- As quoted in The Martians of Science : Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006) by István Hargittai, p. 251

- I believe that no endeavor that is worthwhile is simple in prospect; if it is right, it will be simple in retrospect.

- As quoted in The Martians of Science : Five Physicists Who Changed the Twentieth Century (2006) by István Hargittai, p. 251

- "A stands for atom; it is so small

No one has ever seen it at all.

B stands for bombs; the bombs are much bigger.

So, brother, do not be too fast on the trigger.

F stands for fission; that is what things do

When they get wobbly and big and must split in two.

And just to confound the atomic confusion

What fission has done may be undone by fusion.

H has become a most ominous letter;

It means something bigger, if not something better.

S stands for secret; you can keep it forever —

Provided there's no one abroad who is clever."- "Atom Alphabet", Alamogordo Daily News, from Alamogordo, New Mexico; pg5 of 14 November 1957</poem>

- "Atom Alphabet", Alamogordo Daily News, from Alamogordo, New Mexico; pg5 of 14 November 1957</poem>

Quotes about Teller

[edit]

- Business institutions universities

Both are quite the circus where the killer wants his way

I think of Edward Teller and his moribund reprise

Then I look to Nevada and I can't believe my eyes

It's time for him to die!- Bad Religion, in The Biggest Killer in American History

- Dr. Teller has a mind very different from mine. I think one needs both kinds of minds to make a successful project. I think Dr. Teller's mind runs particularly to making brilliant inventions, but what he needs is some control, some other person who is more able to find out just what is the scientific fact about the matter. Some other person who weeds out the bad from the good ideas.

- Hans Bethe, as quoted in In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer (1954 security hearings), p. 331

- Teller's mistake was his failure to foresee that a large section of the public would not consider his appearance at the Oppenheimer hearing to be decent behavior. Had Teller not appeared, the outcome of the hearing would almost certainly have been unaffected, and the moral force of Teller's position would not have been tainted.

- Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (1979), p. 88

- Before Bethe married, he was so often a guest in the Teller home that he became almost one of the family. In April, 1954, that was all over. There could be no real reconciliation. Bethe had lost one of his oldest friends. But Teller had lost more. Teller, by lending his voice to the cause of Oppenheimer's enemies, had lost not only the friendship but the respect of many of his colleagues, and he was portrayed by newspaper writers and cartoonists as a Judas, a man who had betrayed his leader for the sake of personal gain.

- Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (1979), p. 90

- When we came back through the trees to the house, we heared a strange sound coming through the open door. The children stopped their chatter and we all stood outside the door and listened. It was my old friend from long ago, Bach's Prelude No. 8 in E-flat minor. Superbly played. Played just the way my father used to play it. For a moment I was completely disoriented. I thought: What the devil is my father doing here in California? We stood in front of our Berkeley house and listened to that prelude. Whoever was playing it was putting into it his whole heart and soul. The sound floated up to us like a chorus of mourning from the depths, as if the spirits in the underworld were dancing to a slow pavane. We waited until the music came to an end and then walked in. There, sitting at the piano, was Edward Teller. We asked him to go on playing, but he excused himself.

- Freeman Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (1979), p. 92

- The physicist Edward Teller, known as the “father of the H-bomb,” went further to deny that omnicide—a concept he derided—was remotely feasible. In answer to a question I posed to him as late as 1982, he said emphatically it was “impossible” to kill by any imaginable use of thermonuclear weapons that he had co-invented “more than a quarter of the earth’s population.” At the time, I thought of this assurance, ironically, as his perception of “the glass being three-quarters full.” (Teller was, along with Kahn, Henry Kissinger, and the former Nazi missile designer Wernher von Braun, one of Kubrick’s inspirations for the character of Dr. Strangelove.) And Teller’s estimate was closely in line with what the JCS actually planned to do in 1961, though a better estimate (allowing for the direct effects of fire, which JSC calculations have always omitted) would have been closer to one-third to one-half of total omnicide. But the JCS were mistaken in 1961, and so was Herman Kahn in 1960, and so was Teller in 1982. Nobody’s perfect. Just one year after Teller had made this negative assertion (at a hearing of the California state legislature which we both addressed, on the Bilateral Nuclear Weapons Freeze Initiative), the first papers appeared on the nuclear-winter effects of smoke injected into the stratosphere by firestorms generated by a thousand or more of the fifty thousand existing H-bombs used on cities. Contrary to Kahn and Teller, an American Doomsday Machine already existed in 1961—and had for years—in the form of pre-targeted bombers on alert in the Strategic Air Command (SAC), soon to be joined by Polaris submarine-launched missiles. Although this machine wasn’t likely to kill outright or starve to death literally every last human, its effects, once triggered, would come close enough to that to deserve the name Doomsday.

- Daniel Ellsberg, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner (2017)

- He is a danger to all that is important. I do really feel it would have been a better world without Teller.

- Isidor Isaac Rabi, in a statement of 1968, as quoted in The Myths of August : A Personal Exploration of Our Tragic Cold War Affair With the Atom (1998) by Stewart L. Udall, p. 283

- After he suffered a stroke three years ago, a nurse quizzed him to probe his lucidity. "Are you the famous Edward Teller?" she queried. "No," he snapped. "I'm the infamous Edward Teller."

- Gary Stix in "Infamy and honor at the Atomic Café : Edward Teller has no regrets about his contentious career," Scientific American (October 1999), p 42

External links

[edit]- Edward Teller page at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- LLNL Interview with Edward Teller

- "Edward Teller's Role in the Oppenheimer Hearings" an interview with Richard Rhodes

- Edward Teller's FBI file

- Video excerpts from a televised debate between Edward Teller and Linus Pauling, Fallout and Disarmament (20 February 1958)