Joseph Addison

Appearance

And all of heaven we have below.

Joseph Addison (May 1 1672 – June 17 1719) was an English politician and writer. His name is often remembered in tandem with that of his friend, Richard Steele, with whom he founded The Spectator magazine.

Quotes

[edit]

It wakes the soul, and lifts it high

And imitate the blest above,

In joy, and harmony, and love.

Prolonging every note with art

In airy circles o'er us fly,

Till, wafted by a gentle breeze,

They faint and languish by degrees,

And at a distance die.

What joys, what wonders, have I seen!

Look down on this important hour

In ruin and confusion hurled,

He, unconcerned, would hear the mighty crack,

And stand secure amidst a falling world.

- Music, the greatest good that mortals know,

And all of heaven we have below.- Song for St. Cecilia's Day (1692), st. 3

- Music religious heat inspires,

It wakes the soul, and lifts it high,

And wings it with sublime desires,

And fits it to bespeak the Deity.- Song for St. Cecilia's Day (1692), st. 4

- When time itself shall be no more,

And all things in confusion hurl'd,

Music shall then exert it's power,

And sound survive the ruins of the world:

Then saints and angels shall agree

In one eternal jubilee:

All Heaven shall echo with their hymns divine,

And God himself with pleasure see

The whole creation in a chorus join.- Song for St. Cecilia's Day (1692)

- Consecrate the place and day

To music and Cecilia.

Let no rough winds approach, nor dare

Invade the hallow'd bounds,

Nor rudely shake the tuneful air,

Nor spoil the fleeting sounds.

Nor mournful sigh nor groan be heard,

But gladness dwell on every tongue;

Whilst all, with voice and strings prepar'd,

Keep up the loud harmonious song,

And imitate the blest above,

In joy, and harmony, and love.- Song for St. Cecilia's Day (1692)

- On you, my lord, with anxious fear I wait,

And from your judgment must expect my fate.- A Poem to His Majesty (1695), l. 21

- Let echo, too, perform her part,

Prolonging every note with art;

And in a low expiring strain,

Play all the concert o'er again.- Ode for St. Cecilia's Day (1699), st. 4

- A thousand trills and quivering sounds

In airy circles o'er us fly,

Till, wafted by a gentle breeze,

They faint and languish by degrees,

And at a distance die.- Ode on St. Cecilia's Day (1699), st. 6

- For wheresoe'er I turn my ravished eyes,

Gay gilded scenes and shining prospects rise,

Poetic fields encompass me around,

And still I seem to tread on classic ground.- A Letter from Italy, to the Right Honourable Charles, Lord Halifax (1701)

- Fain would I Raphael's godlike art rehearse,

And show th' immortal labours in my verse,

Where from themingled strength of shade and light

A new creation rises to my sight,

Such heavenly figures from his pencil flow,

So warm with life his blended colours glow.

From theme to theme with secret pleasure tost,

Amidst the soft variety I 'm lost:

Here pleasing airs my ravish'd soul confound

With circling notes and labyrinths of sound;

Here domes and temples rise in distant views,

And opening palaces invite my Muse.- A Letter from Italy (1703)

- When hosts of foes with foes engage,

And round th' anointed hero rage,

The cleaving fauchion I misguide,

And turn the feather'd shaft aside.- Second Angel, in Rosamond (c. 1707), Act III, sc. i

- Where have my ravish'd senses been!

What joys, what wonders, have I seen!

The scene yet stands before my eye,

A thousand glorious deeds that lie

In deep futurity obscure,

Fights and triumphs immature,

Heroes immers'd in time's dark womb,

Ripening for mighty years to come,

Break forth, and, to the day display'd,

My soft inglorious hours upbraid.

Transported with so bright a scheme,

My waking life appears a dream.- Henry in Rosamond (c. 1707), Act III, sc. i

- Every star, and every pow'r,

Look down on this important hour:

Lend your protection and defence

Every guard of innocence!

Help me my Henry to assuage,

To gain his love or bear his rage.

Mysterious love, uncertain treasure,

Hast thou more of pain or pleasure!

Chill'd with tears,

Kill'd with fears,

Endless torments dwell about thee:

Yet who would live, and live without thee!- Queen Elinor in Rosamond (c. 1707), Act III, sc. ii

- The French are certainly the most implacable, and the most dangerous Enemys of the British Nation. Their Form of Government, their Religion, their Jealousy of the British Power, as well as their Prosecutions of Commerce, and Pursuits of Universal Monarchy, will fix them for ever in their Animosities and Aversions towards us, and make them catch at all Opportunities of subverting our Constitution, destroying our Religion, ruining our Trade, and sinking the Figure which we make among the Nations of Europe...

As we are thus in a natural State of War, if I may so call it, with the French Nation; it is our Misfortune, that they are not only the most inveterate, but most formidable of our Enemies; and have the greatest Power, as well as the strongest Inclination to ruin us.- The Present State of the War, and the Necessity of an Augmentation, Consider'd (1708), pp. 1-2

- The French King hath often enter'd on several expensive Projects, on purpose to dissipate the Wealth that is continually gathering in his Coffers in times of peace... But if he once engrosses the commerce of the Spanish Indies, whatever Quantities of Gold and Silver stagnate in his private Coffers, there will be still enough to carry on the Circulation among his Subjects. By this means in a short space of time he may heap up greater Wealth than all the Princes of Europe join'd together; and in the present Constitution of the World, Wealth and Power are but different Names for the same thing. Let us therefore suppose that after eight or ten Years of Peace, he hath a mind to infringe any of his Treaties, or invade a neighbouring State; to revive the pretensions of Spain upon Portugal, or attempt the taking those Places which were granted us for our Security; what Resistance, what Opposition can we make to so formidable an Enemy? Shou'd the same Alliance rise against him that is now in War with him, what cou'd we hope for from it, at a time when the States engag'd in it will be comparatively weaken'd, and the Enemy who is now able to keep them at a stand, will have receiv'd so many new Accessions of Strength.

- The Present State of the War, and the Necessity of an Augmentation, Consider'd (1708), pp. 11-12

- The man resolved, and steady to his trust,

Inflexible to ill, and obstinately just,

May the rude rabble's insolence despise,

Their senseless clamours and tumultuous cries;

The tyrant's fierceness he beguiles,

And the stern brow, and the harsh voice defies,

And with superior greatness smiles.- Translation of Horace, Odes, Book III, ode iii

- Should the whole frame of Nature round him break,

In ruin and confusion hurled,

He, unconcerned, would hear the mighty crack,

And stand secure amidst a falling world.- Translation of Horace, Odes, Book III, ode iii

- When I read the several dates of the tombs, of some that died yesterday, and some six hundred years ago, I consider that great day when we shall all of us be contemporaries, and make our appearance together.

- Thoughts in Westminster Abbey (1711)

- When I read the epitaphs of the beautiful, every inordinate desire goes out; when I meet with the grief of parents upon a tombstone, my heart melts with compassion; when I see the tomb of the parents themselves, I consider the vanity of grieving for those whom we must quickly follow: when I see kings lying by those who deposed them, when I consider rival wits placed side by side, or the holy men that divided the world with their contests and disputes, I reflect with sorrow and astonishment on the little competitions, factions, and debates of mankind.

- Thoughts in Westminster Abbey (1711)

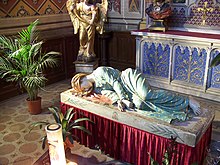

- See in what peace a Christian can die!

- Last words, to his stepson (1719), as quoted in Conjectures on Original Composition (1759) by Edward Young

- Variants:

- I have sent for you that you may see in what peace a Christian may die.

- As quoted in The R. I. Schoolmaster, Vol. V (1859), edited by William A. Mowry and Henry Clark, p. 71

- I have sent for you that you may see how a Christian may die.

- As quoted in Famous Sayings and their Authors (1906) by Edward Latham

The Campaign (1704)

[edit]

Demand alliance, and in friendship burn

And lost in one promiscuous carnage lie.

And, pleas'd th' Almighty's orders to perform,

Rides in the whirlwind, and directs the storm.

- Great souls by instinct to each other turn,

Demand alliance, and in friendship burn;

A sudden friendship, while with stretched-out rays

They meet each other, mingling blaze with blaze.

Polished in courts, and hardened in the field,

Renowned for conquest, and in council skilled,

Their courage dwells not in a troubled flood

Of mounting spirits, and fermenting blood:

Lodged in the soul, with virtue overruled,

Inflamed by reason, and by reason cooled,

In hours of peace content to be unknown.

And only in the field of battle shown:

To souls like these, in mutual friendship joined,

Heaven dares intrust the cause of humankind.- Line 101

- Nations with nations mix'd confus'dly die,

And lost in one promiscuous carnage lie.- Line 152

- Unbounded courage and compassion join'd,

Tempering each other in the victor's mind,

Alternately proclaim him good and great,

And make the hero and the man complete.- Line 219

- So when an angel by divine command

With rising tempests shakes a guilty land,

Such as of late o'er pale Britannia passed,

Calm and serene he drives the furious blast;

And, pleas'd th' Almighty's orders to perform,

Rides in the whirlwind, and directs the storm.- Line 287, the word "passed" was here originally spelt "past" but modern renditions have updated the spelling for clarity. An alteration of these lines occurs in Alexander Pope's satire The Dunciad, Book III, line 264, where he describes a contemporary theatre manager as an "Angel of Dulness":

- Immortal Rich! how calm he sits at ease,

Midst snows of paper, and fierce hail of pease;

And proud his mistress' order to perform,

Rides in the whirlwind and directs the storm.

- Immortal Rich! how calm he sits at ease,

- O Dormer, how can I behold thy fate,

And not the wonders of thy youth relate;

How can I see the gay, the brave, the young,

Fall in the cloud of war, and lie unsung!

In joys of conquest he resigns his breath,

And, filled with England's glory, smiles in death.- Line 309

- Rais'd of themselves, their genuine charms they boast,

And those who paint them truest praise them most.- last lines

Cato, A Tragedy (1713)

[edit]

Some hidden thunder in the stores of heaven,

Red with uncommon wrath, to blast the man

Who owes his greatness to his country's ruin?

But we'll do more, Sempronius; we'll deserve it.

Is worth a whole eternity in bondage.

That we can die but once to serve our country!

- Is there not some chosen curse,

Some hidden thunder in the stores of heaven,

Red with uncommon wrath, to blast the man

Who owes his greatness to his country's ruin?- Act I, scene i

- The dawn is overcast, the morning lowers,

And heavily in clouds brings on the day,

The great, the important day,

Big with the fate Of Cato, and of Rome.- Act I, scene i

- Thy steady temper, Portius,

Can look on guilt, rebellion, fraud, and Cæsar,

In the calm lights of mild philosophy.- Act I, scene i

- Love is not to be reason'd down, or lost

In high ambition, and a thirst of greatness;

'Tis second life, it grows into the soul,

Warms every vein, and beats in every pulse.- Act I, scene i

- 'Tis not in mortals to command success,

But we'll do more, Sempronius; we'll deserve it.- Act I, scene ii

- Thy father's merit sets thee up to view,

And shows thee in the fairest point of light,

To make thy virtues, or thy faults, conspicuous.- Act I, scene ii

- Oh! think what anxious moments pass between

The birth of plots, and their last fatal periods,

Oh! 'tis a dreadful interval of time,

Filled up with horror all, and big with death!- Act I, scene iii

- Better to die ten thousand deaths,

Than wound my honour.- Act I, scene iv

- If the following day he chance to find

A new repast, or an untasted spring,

Blesses his stars, and thinks it luxury.- Act I, scene iv

- 'Tis pride, rank pride, and haughtiness of soul:

I think the Romans call it Stoicism.- Act I, scene iv

- Were you with these, my prince, you'd soon forget

The pale, unripened beauties of the north.- Act I, scene iv

- Beauty soon grows familiar to the lover,

Fades in his eye, and palls upon the sense.- Act I, scene iv

- My voice is still for war.

Gods! Can a Roman senate long debate

Which of the two to choose, slavery or death?

No, let us rise at once,

Gird on our swords, and,

At the head of our remaining troops, attack the foe,

Break through the thick array of his throng'd legions,

And charge home upon him.

Perhaps some arm, more lucky than the rest,

May reach his heart, and free the world from bondage.- Act II, scene i

- A day, an hour, of virtuous liberty

Is worth a whole eternity in bondage.- Act II, scene i

- Great Pompey's shade complains that we are slow,

And Scipio's ghost walks unavenged amongst us!- Act II, scene i

- Young men soon give and soon forget affronts;

Old age is slow in both.- Act II, scene v

- The friendships of the world are oft

Confederacies in vice, or leagues of pleasure;

Ours has severest virtue for its basis,

And such a friendship ends not but with life.- Act III, scene i

- When love's well-timed 'tis not a fault of love;

The strong, the brave, the virtuous, and the wise,

Sink in the soft captivity together.- Act III, scene i

- Loveliest of women! heaven is in thy soul,

Beauty and virtue shine forever round thee,

Bright'ning each other! thou art all divine!- Act III, scene ii

- Talk not of love: thou never knew'st its force.

- Act III, scene ii

- To my confusion, and eternal grief,

I must approve the sentence that destroys me.- Act III, scene ii

- See they suffer death,

But in their deaths remember they are men,

Strain not the laws to make their tortures grievous.- Act III, scene v

- Why wilt thou add to all the griefs I suffer

Imaginary ills, and fancy'd tortures?- Act IV, scene i

- When love once pleas admission to our hearts,

(In spite of all the virtue we can boast),

The woman that deliberates is lost.- Variant: "When love once pleads admission to our hearts..."

- Act IV, scene i. The last line has often been misreported as "He who hesitates is lost", a sentiment inspired by it but not penned by Addison. See Paul F. Boller, Jr., and John George, They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, & Misleading Attributions (1989), p. 3

- I will indulge my sorrows, and give way

To all the pangs and fury of despair.- Act IV, scene iii

- Curse on his virtues! they've undone his country.

- Act IV, scene iv

- How beautiful is death, when earn'd by virtue!

Who would not be that youth? What pity is it

That we can die but once to serve our country!- Act IV, scene iv

- Content thyself to be obscurely good.

When vice prevails, and impious men bear sway,

The post of honor is a private station.- Act IV, scene iv

- O ye powers that search

The heart of man, and weigh his inmost thoughts,

If I have done amiss, impute it not!

The best may err, but you are good.- Act IV, scene iv

- Thanks to the gods! my boy has done his duty.

- Act IV, scene iv

- The honors of this world, what are they

But puff, and emptiness, and peril of falling?- Act IV, scene iv

- The stars shall fade away, the sun himself

Grow dim with age, and nature sink in years,

But thou shalt flourish in immortal youth,

Unhurt amidst the wars of elements,

The wrecks of matter, and the crush of worlds.- Act V, scene i

(And that there is all nature cries aloud

Through all her works) he must delight in virtue.

- If there's a power above us,

(And that there is all nature cries aloud

Through all her works) he must delight in virtue.- Act V, scene i

- It must be so — Plato, thou reasonest well!

Else whence this pleasing hope, this fond desire,

This longing after immortality?

Or whence this secret dread, and inward horror,

O falling into nought? Why shrinks the soul

Back on herself, and startles at destruction?

'Tis the divinity that stirs within us;

'Tis heaven itself, that points out an hereafter,

And intimates eternity to man.- Act V, scene i

- Eternity! thou pleasing dreadful thought!

Through what variety of untried being,

Through what new scenes and changes must we pass!- Act V, scene i

- I'm weary of conjectures,—this must end 'em.

Thus am I doubly armed: my death and life,

My bane and antidote, are both before me:

This in a moment brings me to an end;

But this informs me I shall never die.

The soul, secured in her existence, smiles

At the drawn dagger, and defies its point.

The stars shall fade away, the sun himself

Grow dim with age, and Nature sink in years;

But thou shalt flourish in immortal youth,

Unhurt amidst the war of elements,

The wrecks of matter, and the crush of worlds.- Act V, scene i

- Nature does nothing without purpose or uselessly.

- Act V, scene i

- The ideal man bears the accidents of life

With dignity and grace, the best of circumstances.- Act V, scene i

- The soul, secured in her existence, smiles

At the drawn dagger, and defies its point.- Act V, scene i

- What means this heaviness that hangs upon me?

This lethargy that creeps through all my senses?

Nature, oppress'd and harrass'd out with care,

Sinks down to rest.- Act V, scene i

- Sweet are the slumbers of the virtuous man.

- Act V, scene iv

- From hence, let fierce contending nations know,

What dire effects from civil discord flow.- Act V, scene iv

The Guardian (1713)

[edit]

- There is no virtue so truly great and godlike as justice.

- No. 99

- To be perfectly just is an attribute in the divine nature; to be so to the utmost of our abilities, is the glory of man.

- No. 99

- Justice discards party, friendship, kindred, and is therefore always represented as blind.

- No. 99

- Knowledge is, indeed, that which, next to virtue, truly and essentially raises one man above another.

- No. 111

- When I read the rules of criticism, I immediately inquire after the works of the author who has written them, and by that means discover what it is he likes in a composition.

- No. 115

- Courage that grows from constitution very often forsakes a man when he has occasion for it, and when it is only a kind of instinct in the Soul breaks out on all occasions without judgment or discretion. That courage which proceeds from the sense of our duty, and from the fear of offending Him that made us, acts always in a uniform manner, and according to the dictates of right reason.

- No. 117

- Blessings may appear under the shape of pains, losses and disappointments; but let him have patience, and he will see them in their proper figures.

- No. 117

- A good conscience is to the soul what health is to the body; it preserves a constant ease and serenity within us, and more than countervails all the calamities and afflictions which can possibly befall us.

- No. 135

- The sense of honour is of so fine and delicate a nature, that it is only to be met with in minds which are naturally noble, or in such as have been cultivated by good examples, or a refined education.

- No. 161

- Charity is a virtue of the heart, and not of the hands.

- No. 166

- Gifts and alms are the expressions, not the essence, of this virtue.

- No. 166

The Spectator (1711–1714)

[edit]

- If I can any way contribute to the diversion or improvement of the country in which I live, I shall leave it, when I am summoned out of it, with the secret satisfaction of thinking that I have not lived in vain.

- No. 1 (1 March 1711)

- Thus I live in the world rather as a spectator of mankind than as one of the species.

- No. 1 (1 March 1711)

- To be exempt from the passions with which others are tormented, is the only pleasing solitude.

- No. 4 (5 March 1711)

- I would... earnestly advise them for their good to order this paper to be punctually served up, and to be looked upon as a part of the tea equipage.

- No. 10 (11 March 1711)

- I shall endeavor to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality.

- No. 10 (11 March 1711)

- True happiness is of a retired nature, and an enemy to pomp and noise; it arises, in the first place, from the enjoyment of one's self, and in the next, from the friendship and conversation of a few select companions.

- No. 15 (March 17, 1711)

- That nothing is capable of being well set to Musick, that is not Nonsense.

- No. 18 (March 21, 1711)

- The Fear of Death often proves Mortal, and sets People on Methods to save their Lives, which infallibly destroy them.

- No. 25 (29 March 1711)

- It is indeed very possible, that the Persons we laugh at may in the main of their Characters be much wiser Men than our selves; but if they would have us laugh at them, they must fall short of us in those Respects which stir up this Passion.

- No. 47 (24 April 1711)

- In all thy humours, whether grave or mellow,

Thou 'rt such a touchy, testy, pleasant fellow,

Hast so much wit and mirth and spleen about thee,

There is no living with thee, nor without thee.- No. 68 (18 May 1911)

- There is not a more unhappy being than a superannuated idol.

- No. 73 (24 May 1711)

- A man that has a taste of music, painting, or architecture, is like one that has another sense, when compared with such as have no relish of those arts.

- No. 93 (16 June 1711)

- Of all the diversions of life, there is none so proper to fill up its empty spaces as the reading of useful and entertaining authors.

- No. 94 (18 June 1711)

- There is not so variable a thing in Nature as a lady's head-dress.

- No. 98 (22 June 1711)

- "Censure," says a late ingenious author, "is the tax a man plays for being eminent." It is a folly for an eminent man to think of escaping it, and a weakness to be affected with it. All the illustrious persons of antiquity, and indeed of every age in the world, have passed through this fiery persecution. There is no defense against reproach but obscurity; it is a kind of comitant to greatness, as satires and invectives were an essential part of a Roman triumph.

- No. 101 (26 June 1711)

- If men of eminence are exposed to censure on one hand, they are as much liable to flattery on the other. If they receive reproaches which are not due to them, they likewise receive praises which they do not deserve. In a word, the man in a high post is never regarded with an indifferent eye, but always considered as a friend or an enemy. For this reason persons in great stations have seldom their true characters drawn till several years after their deaths. Their personal friendships and enmities must cease, and the parties they were engaged in be at an end, before their faults or their virtues can have justice done them. When writers have the least opportunity of knowing the truth, they are in the best disposition to tell it.

It is therefore the privilege of posterity to adjust the characters of illustrious persons, and to set matters right between those antagonists who by their rivalry for greatness divided a whole age into factions.- No. 101 (26 June 1711), this has sometimes been quoted as "It is the privilege of posterity to set matters right between those antagonists who, by their rivalry for greatness, divided a whole age".

- Sunday clears away the rust of the whole week.

- No. 112 (9 July 1711)

- Exercise ferments the humors, casts them into their proper channels, throws off redundancies, and helps nature in those secret distributions, without which the body cannot subsist in its vigor, nor the soul act with cheerfulness.

- No. 115 (12 July 1711)

- When I consider the Question, Whether there are such Persons in the World as those we call Witches? my Mind is divided between the two opposite Opinions; or rather (to speak my Thoughts freely) I believe in general that there is, and has been such a thing as Witchcraft; but at the same time can give no Credit to any Particular Instance of it.

- No. 117 (14 July 1711)

- Animals in their generation are wiser than the sons of men; but their wisdom is confined to a few particulars, and lies in a very narrow compass.

- No. 120 (18 July 1711)

- The most violent appetites in all creatures are lust and hunger: the first is a perpetual call upon them to propogate their kind; the latter to preserve themselves.

- No. 120 (18 July 1711)

- Much might be said on both sides.

- No. 122 (20 July 1711)

- A man's first care should be to avoid the reproaches of his own heart; his next to escape the censures of the world: if the last interferes with the former, it ought to be entirely neglected; but otherwise there cannot be a greater satisfaction to an honest mind, than to see those approbations which it gives itself seconded by the applauses of the public: a man is more sure of his conduct, when the verdict which he passes upon his own behaviour is thus warranted and confirmed by the opinion of all that know him.

- On "Sir Roger", in No. 122 (20 July 1711)

- Authors have established it as a kind of rule, that a man ought to be dull sometimes; as the most severe reader makes allowances for many rests and nodding places in a voluminous writer.

- No. 124 (23 July 1711)

- A cloudy day or a little sunshine have as great an influence on many constitutions as the most real blessings or misfortunes.

- No. 162 (5 September 1711)

- Mutability of temper and inconsistency with ourselves is the greatest weakness of human nature.

- No. 162 (5 September 1711)

- The circumstance which gives authors an advantage above all these great masters, is this, that they can multiply their originals; or rather, can make copies of their works, to what number they please, which shall be as valuable as the originals themselves.

- No. 166 (10 September 1711)

- Books are the legacies that a great genius leaves to mankind, which are delivered down from generation to generation, as presents to the posterity of those who are yet unborn.

- No. 166 (10 September 1711)

- Man is subject to innumerable pains and sorrows by the very condition of humanity, and yet, as if nature had not sown evils enough in life, we are continually adding grief to grief, and aggravating the common calamity by our cruel treatment of one another.

- No. 169 (13 September 1711)

- Good nature is more agreeable in conversation than wit, and gives a certain air to the countenance which is more amiable than beauty.

- No. 169 (13 September 1711)

- I have somewhere met with the epitaph of a charitable man, which has very much pleased me. I cannot recollect the words, but the sense of it is to this purpose; What I spent I lost; what I possessed is left to others; what I gave away remains with me.

- No. 177 (22 September 1711)

- I would fain ask one of these bigotted Infidels, supposing all the great Points of Atheism … were laid together and formed into a kind of Creed, according to the Opinions of the most celebrated Atheists; I say, supposing such a Creed as this were formed, and imposed upon any one People in the World, whether it would not require an infinitely greater Measure of Faith, than any Set of Articles which they so violently oppose.

- No. 185 (2 October 1711).

- Often misquoted as "To be an atheist requires an infinitely greater measure of faith than to receive all the great truths which atheism would deny."

- The man who will live above his present circumstances is in great danger of living in a little time much beneath them; or as the Italian proverb runs, "The man who lives by hope, will die by hunger."

- No. 191 (9 October 1711)

- Were I to prescribe a rule for drinking, it should be formed upon a saying quoted by Sir William Temple: the first glass for myself, the second for my friends, the third for good humor, and the fourth for mine enemies.

- No. 195 (13 October 1711)

- I consider an human soul without education like marble in the quarry, which shews none of its inherent beauties till the skill of the polisher fetches out the colours, makes the surface shine, and discovers every ornamental cloud, spot and vein that runs through the body of it.

- No. 215 (6 November 1711)

- What sculpture is to a block of marble, education is to the human soul.

- No. 215 (6 November 1711)

- Discretion is a perfection of reason, and a guide to us in all the duties of life.

- No. 225 (17 November 1711)

- A just and reasonable modesty does not only recommend eloquence, but sets off every great talent which a man can be possessed of.

- No. 231 (24 November 1711)

- Mere bashfulness without merit is awkward; and merit without modesty, insolent. But modest merit has a double claim to acceptance, and generally meets with as many patrons as beholders.

- No. 231 (24 November 1711)

- Modesty is not only an ornament, but also a guard to virtue.

- No. 231 (24 November 1711)

- A man must be excessively stupid, as well as uncharitable, who believes that there is no virtue but on his own side, and that there are not men as honest as himself who may differ from him in political principles.

- No. 243 (8 December 1711)

- What an absurd thing it is to pass over all the valuable parts of a man, and fix our attention on his infirmities.

- No. 249 (15 December 1711)

- Were not this desire of fame very strong, the difficulty of obtaining it, and the danger of losing it when obtained, would be sufficient to deter a man from so vain a pursuit.

- No. 255 (22 December 1711)

- Admiration is a very short-lived passion that immediately decays upon growing familiar with its object, unless it be still fed with fresh discoveries, and kept alive by a new perpetual succession of miracles rising up to its view.

- No. 256 (24 December 1711)

- Often only the first half of this statement is quoted

- Ambition raises a secret tumult in the soul, it inflames the mind, and puts it into a violent hurry of thought.

- No. 256 (24 December 1711)

- Some virtues are only seen in affliction and some in prosperity.

- No. 257 (25 December 1711)

- I have often thought, says Sir Roger, it happens very well that Christmas should fall out in the Middle of the Winter

- No. 269 (8 January 1712)

- A true critic ought to dwell rather upon excellencies than imperfections, to discover the concealed beauties of a writer, and communicate to the world such things as are worth their observation.

- No. 291 (2 February 1712)

- These widows, sir, are the most perverse creatures in the world.

- No. 335 (25 March 1712)

- Death only closes a Man's Reputation, and determines it as good or bad.

- No. 349 (10 April 1712); famously seen on the brothel wall in the film Easy Rider.

- Mirth is like a flash of lightning, that breaks through a gloom of clouds, and glitters for a moment; cheerfulness keeps up a kind of daylight in the mind, and fills it with a steady and perpetual serenity.

- No. 381 (17 May 1712)

- Sir Roger made several reflections on the greatness of the British Nation; as, that one Englishman could beat three Frenchmen; that we could never be in danger of Popery so long as we took care of our fleet; that the Thames was the noblest river in Europe...with many other honest prejudices which naturally cleave to the heart of a true Englishman.

- No. 383 (20 May 1712)

- Cheerfulness is...the best promoter of health.

- No. 387 (24 May 1712)

- Health and cheerfulness mutually beget each other.

- No. 387 (24 May 1712)

With all the blue ethereal sky,

And spangled heavens, a shining frame,

Their great Original proclaim.

- Everything that is new or uncommon raises a pleasure in the imagination, because it fills the soul with an agreeable surprise, gratifies its curiosity, and gives it an idea of which it was not before possessed.

- No. 412 (23 June 1712)

- The Lord my pasture shall prepare,

And feed me with a shepherd's care;

His presence shall my wants supply,

And guard me with a watchful eye.- No. 444 (26 July 1712)

- Our delight in any particular study, art, or science rises and improves in proportion to the application which we bestow upon it. Thus, what was at first an exercise becomes at length an entertainment.

- No. 447 (2 August 1712)

- When all thy mercies, O my God,

My rising soul surveys,

Transported with the view, I'm lost

In wonder, love and praise.- No. 453 (9 August 1712)

- The spacious firmament on high,

With all the blue ethereal sky,

And spangled heavens, a shining frame,

Their great Original proclaim.- No. 465, Ode (23 August 1712).

- Also in The Polite Arts (1749), Chap. XXI. "Of Lyrick Poetry."

- Soon as the evening shades prevail,

The moon takes up the wondrous tale,

And nightly to the listening earth

Repeats the story of her birth;

While all the stars that round her burn,

And all the planets in their turn,

Confirm the tidings as they roll,

And spread the truth from pole to pole.- No. 465, Ode (23 August 1712)

- What though no real voice nor sound

Amid their radiant orbs be found ;

In reason's ear they all rejoice,

And utter forth a glorious voice,

Forever singing as they shine,

"The Hand that made us divine."- No. 465, Ode (23 August 1712)

- A woman seldom asks advice before she has bought her wedding clothes.

- No. 475 (4 September 1712)

- Method is not less requisite in ordinary conversation than in writing, provided a man would talk to make himself understood.

- No. 476 (5 September 1712)

- Our disputants put me in mind of the skuttle fish, that when he is unable to extricate himself, blackens all the water about him, till he becomes invisible.

- No. 476 (5 September 1712)

- Irregularity and want of method are only supportable in men of great learning or genius, who are often too full to be exact, and therefore choose to throw down their pearls in heaps before the reader, rather than be at the pains of stringing them.

- No. 476 (5 September 1712)

- I value my garden more for being full of blackbirds than cherries, and very frankly give them fruit for their songs.

- No. 477 (6 September 1712)

- The fraternity of the henpecked.

- No. 482 (12 September 1712)

- If we may believe our logicians, man is distinguished from all other creatures by the faculty of laughter.

- No. 494 (26 September 1712)

- There is nothing which we receive with so much reluctance as advice.

- No. 512 (17 October 1712)

- If we hope for what we are not likely to possess, we act and think in vain, and make life a greater dream and shadow than it really is.

- No. 535 (13 November 1712)

- An ostentatious man will rather relate a blunder or an absurdity he has committed, than be debarred from talking of his own dear person.

- No. 562 (2 July 1714)

- A man should always consider how much he has more than he wants.

- No. 574 (30 July 1714)

- Upon the whole, a contented mind is the greatest blessing a man can enjoy in this world.

- No. 574 (30 July 1714)

- We are always doing something for Posterity, but I would fain see Posterity do something for us.

- No. 587 (20 August 1714)

The Tatler (1711–1714)

[edit]- Men may change their climate, but they cannot change their nature. A man that goes out a fool cannot ride or sail himself into common sense.

- No. 93

- Silence never shows itself to so great an advantage, as when it is made the reply to calumny and defamation, provided that we give no just occasion for them.

- No. 133

- A misery is not to be measured from the nature of the evil, but from the temper of the sufferer.

- No. 146

- Reading is to the mind, what exercise is to the body. As by the one, health is preserved, strengthened, and invigorated: by the other, virtue (which is the health of the mind) is kept alive, cherished, and confirmed.

- No. 147

- A cheerful temper joined with innocence will make beauty attractive, knowledge delightful and wit good-natured.

- No. 192

- Advertisements are of great use to the vulgar. First of all, as they are instruments of ambition. A man that is by no means big enough for the Gazette, may easily creep into the advertisements; by which means we often see an apothecary in the same paper of news with a plenipotentiary, or a running footman with an ambassador.

- No. 224

- The great art in writing advertisements is the finding out a proper method to catch the reader's eye; without which a good thing may pass over unobserved, or be lost among commissions of bankrupt.

- No. 224

- I Have often thought if the minds of men were laid open, we should see but little difference between that of the wise man and that of the fool. There are infinite reveries, numberless extravagances, and a perpetual train of vanities which pass through both. The great difference is, that the first knows how to pick and cull his thoughts for conversation, by suppressing some, and communicating others; whereas the other lets them all indifferently fly out in words.

- No. 225

- There are many more shining qualities in the mind of man, but there is none so useful as discretion; it is this, indeed, which gives a value to all the rest, which sets them at work in their proper times and places, and turns them to the advantage of the person who is possessed of them. Without it, learning is pedantry, and wit impertinence; virtue itself looks like weakness; the best parts only qualify a man to be more sprightly in errors, and active to his own prejudice.

- No. 225

- The discreet man finds out the talents of those he converses with, and knows how to apply them to proper uses. Accordingly, if we look into particular communities and divisions of men, we may observe that it is the discreet man, not the witty, nor the learned, nor the brave, who guides the conversation, and gives measures to the society.

- No. 225

- Though a man has all other perfections, and wants discretion, he will be of no great consequence in the world; but if he has this single talent in perfection, and but a common share of others, he may do what he pleases in his station of life.

- No. 225

- At the same time that I think discretion the most useful talent a man can be master of, I look upon cunning to be the accomplishment of little, mean, ungenerous minds. Discretion points out the noblest ends to us, and pursues the most proper and laudable methods of attaining them: cunning has only private selfish aims, and sticks at nothing which may make them succeed. Discretion has large and extended views, and, like a well-formed eye, commands a whole horizon: cunning is a kind of short-sightedness, that discovers the minutest objects which are near at hand, but is not able to discern things at a distance. Discretion the more it is discovered, gives a greater authority to the person who possesses it: cunning, when it is once detected, loses its force, and makes a man incapable of bringing about even those events which he might have done had he passed only for a plain man. Discretion is the perfection of reason, and a guide to us in all the duties of life: cunning is a kind of instinct, that only looks out after our immediate interest and welfare. Discretion is only found in men of strong sense and good understandings, cunning is often to be met with in brutes themselves, and in persons who are but the fewest removes from them.

- No. 225

- Cunning is only the mimic of discretion, and may pass upon weak men in the same manner as vivacity is often mistaken for wit, and gravity for wisdom.

- No. 225

- The cast of mind which is natural to a discreet man, make him look forward into futurity, and consider what will be his condition millions of ages hence, as well as what it is at present. He knows that the misery or happiness which are reserved for him in another world, lose nothing of their reality by being placed at so great a distance from him. The objects do not appear little to him because they are remote. He considers that those pleasures and pains which lie hid in eternity, approach nearer to him every moment, and will be present with him in their full weight and measure, as much as those pains and pleasures which he feels at this very instant. For this reason he is careful to secure to himself that which is the proper happiness of his nature, and the ultimate design of his being. He carries his thoughts to the end of every action, and considers the most distant as well as the most immediate effects of it. He supersedes every little prospect of gain and advantage which offers itself here, if he does not find it consistent with his views of an hereafter. In a word, his hopes are full of immortality, his schemes are large and glorious, and his conduct suitable to one who knows his true interest, and how to pursue it by proper methods.

- No. 225

The free-holder: or political essays, (1716)

[edit]- I have only one Request to make to my Readers, that they will peruse these Papers with the same Candor and Impartiality in which they are written; and shall hope for no other Prepossession in favor of them, than what one would think should be natural to every Man, a Desire to be happy, and a good Will towards those, who are the Instruments of making them so.

- No. 1. Friday, December 23. 1715

- I have rather chosen this Title than any other, because it is what I most glory in, and what most effectually calls to my Mind the Happiness of that Government under which I live. As a British Free-Holder, I should not scruple taking place of a French Marquis; and when I see one of my Countrymen amusing himself in his little Cabbage-Garden, I naturally look upon him as a greater Person than the Owner of the richest Vineyard in Champagne.

- No. 1. Friday, December 23. 1715

- The House of Commons is the Representative of Men in my Condition. I consider my self as one who give my Consent to every Law which passes: A Free-Holder in our Government being of the Nature of a Citizen of Rome in that famous Commonwealth; who, by the Election of a Tribune, had a kind of remote Voice in every Law that was enacted. So that a Freeholder is but one Remove from a Legislator, and for that Reason ought to stand up in the Defense of those Laws, which are in some degree of his own making. For such is the Nature of our happy Constitution, that the Bulk of the People virtually give their Approbation to every thing they are bound to obey, and prescribe to themselves those Rules by which they are to walk.

- No. 1. Friday, December 23. 1715

- How can we sufficiently extol the Goodness of His present Majesty, who is not willing to have a single Slave in his Dominions! Or enough rejoice in the Exercise of that Loyalty, which, instead of betraying a Man into the most ignominious Servitude, (as it does in some of our neighboring Kingdoms) entitles him to the highest Privileges of Freedom and Property!

- No. 1. Friday, December 23. 1715.

- I have lived in one Reign, when the Prince, instead of invigorating the Laws of our Country, or giving them their proper Course, assumed a Power of dispensing with them: And in another, when the Sovereign was flattered by a Set of Men into a Persuasion, that the Regal Authority was unlimited and uncircumscribed. In either of these Cases, good Laws are at best but a dead Letter; and by shewing the People how happy they ought to be, only serve to aggravate the Sense of their Oppressions.

- No. 2 Monday,(26 December 1715)

- It is with great Satisfaction I observe, that the Women of our Island, who are the most eminent for Virtue and good Sense, are in the Interest of the present Government. As the fair Sex very much recommend the Cause they are engaged in, it would be no small Misfortune to a Sovereign, tho' he had all the Male Part of the Nation on his Side, if he did not find himself King of the most beautiful Half of his Subjects. Ladies are always of great use to the Party they espouse, and never fail to win over Numbers to it.

- No. 4 Monday, (2 January 1716)

- The Female World are likewise indispensably necessary in the best Causes to manage the Controversial Part of them, in which no Man of tolerable Breeding is ever able to refute them. Arguments out of a pretty Mouth are unanswerable.

- No. 4 Monday, (2 January 1716)

- There is no greater sign of a general decay of virtue in a nation, than a want of zeal in its inhabitants for the good of their country. This generous and public-spirited Passion has been observed of late Years to languish and grow cold in this our Island; where a Party of Men have made it their Business to represent it as chimerical and romantic, to destroy in the Minds of the People the Sense of national Glory, and to turn into Ridicule our natural and ancient Allies, who are united to us by the common interests both of Religion and Policy.

- No. 5 (6 January 1716)

- It may not therefore be unseasonable to recommend to this present Generation the Practice of that Virtue, for which their Ancestors were particularly famous, and which is called The Love of one's Country. This Love to our Country, as a moral Virtue, is a fixed Disposition of Mind to promote the Safety; Welfare, and Reputation of the Community in which we are born, and of the Constitution under which we are protected

- No. 5 (6 January 1716)

- Though there is a benevolence due to all mankind, none can question but a superior degree of it is to be paid to a father, a wife, or a child. In the same manner, though our love should reach to the whole species, a greater proportion of it should exert itself towards that community in which Providence has placed us. This is our proper sphere of action, the province allotted us for the exercise of our civil virtues, and in which alone we have opportunities of expressing our good-will to mankind.

- No. 5 (6 January 1716)

- We are told, that in Turkey, when any Man is the Author of Notorious Falsehoods, it is usual to blacken the whole Front of his House. Nay we have sometimes heard, that an Embassador, whose Business it is (if I may quote his Character in Sir Henry Wotton's Words) to lie for the Good of his Country, has sometimes had this Mark set upon his House; when he been detected in any Piece of feign'd Intelligence, that has prejudiced the Government, and misled the Minds of the People. One could almost wish that the Habitations of such of our own Countrymen as deal in Forgeries detrimental to the Public, were distinguished in the same Manner; that their Fellow-Subjects might be cautioned not to be too easy in giving Credit to them. Were such a Method put in Practice, this Metropolis would be strangely checquered; some entire Parishes would be in Mourning, and several Streets darkened from one End to the other.

- No. 17. Friday, February 17

- I question not but the more virtuous and considerate parts of our malcontents are now stung with a very just remorse, for this their manner of proceeding, which has so visibly tended to the destruction of their friends, and the sufferings of their country. This may, at the same time, prove an instructive lesson to the boldest and bravest among the disaffected, not to build any hopes upon the talkative zealots of their party; who have shown, by their whole behaviour, that their hearts are equally filled with treason and cowardice.

- No. 28. Monday, March 26, 1716

- An army of trumpeters would give as great a strength to a cause, as this confederacy of tongue-warriors; who, like those military musicians, content themselves with animating their friends to battle, and run out of the engagement upon the first onset. No. 28. Monday, March 26, 1716

- No. 28. Monday, March 26, 1716

- Prejudice and self-sufficiency naturally proceed from inexperience of the world, and ignorance of mankind.

- No. 30 (2 April 1716)

- When men are easy in their circumstances, they are naturally enemies to innovations.

- No. 42 (16 May 1716)

- As to the Reasonings in these several Papers, I must leave them to the Judgment of others. I have taken particular Care that they should be conformable to our Constitution, and free from that Mixture of Violence and Passion, which so often creeps into the Works of Political Writers.

- No. 55 (Friday, 29 June 1716)

- A good Cause doth not want any Bitterness to support it, as a bad one cannot subsist without it. It is indeed observable, that an Author is scurrilous in proportion as he is dull; and seems rather to be in a Passion, because he cannot find out what to say for his own Opinion, than because he has discovered any pernicious Absurdities in that of his Antagonists.

- No. 55 (Friday, 29 June 1716)

The Drummer (1716)

[edit]

Let me tell you, that's the very next step to being dull.

- Round-heads and Wooden-shoes are standing jokes.

- prologue, l. 8

- We are growing serious, and,

Let me tell you, that's the very next step to being dull.- Act IV, sc. vi

- Antidotes are what you take to prevent dotes.

- Act IV, sc. vi

- There is nothing more requisite in business than dispatch.

- Act V, sc. 1

Essays and Tales (1888)

[edit]The Vision of Mirza

[edit]- When I was at Grand Cairo, I picked up several Oriental manuscripts... Among others I met with one entitled “The Visions of Mirza,” which I have read over with great pleasure... I have translated word for word as follows:

- On the fifth day of the moon, which, according to the custom of my forefathers, I always keep holy, after having washed myself, and offered up my morning devotions, I ascended the high hills of Bagdad, in order to pass the rest of the day in meditation and prayer.

- As I was here airing myself on the tops of the mountains, I fell into a profound contemplation on the vanity of human life; and passing from one thought to another, ‘Surely,’ said I, ‘man is but a shadow, and life a dream.’

- I cast my eyes towards the summit of a rock that was not far from me, where I discovered one in the habit of a shepherd, with a musical instrument in his hand... and began to play upon it. The sound of it was exceeding sweet, and wrought into a variety of tunes that were inexpressibly melodious, and altogether different from anything I had ever heard. ...My heart melted away in secret raptures.

- The genius smiled upon me with a look of compassion and affability that familiarised him to my imagination, and at once dispelled all the fears and apprehensions with which I approached him. He lifted me from the ground, and, taking me by the hand, ‘Mirza,’ said he, ‘I have heard thee in thy soliloquies; follow me.’

- He then led me to the highest pinnacle of the rock, and placing me on the top of it, ‘Cast thy eyes eastward,’ said he, ‘and tell me what thou seest.’ ‘I see,’ said I, ‘a huge valley, and a prodigious tide of water rolling through it.’ ‘The valley that thou seest,’ said he, ‘is the Vale of Misery, and the tide of water that thou seest is part of the great tide of Eternity.’

- I then turned again to the vision which I had been so long contemplating: but instead of the rolling tide, the arched bridge, and the happy islands, I saw nothing but the long hollow valley of Bagdad, with oxen, sheep, and camels grazing upon the sides of it.

Disputed

[edit]- If you wish success in life, make perseverance your bosom friend, experience your wise counselor, caution your elder brother and hope your guardian genius.

- The earliest appearance of this proverb yet located is in Eliza Cook's Journal Vol. 11, (1854), p. 128, and the earliest attribution to Addison yet found is in Henry Southgate, ed., Many Thoughts of Many Minds (1862), p. 600.

- What sunshine is to flowers, smiles are to humanity. These are but trifles, to be sure; but scattered along life's pathway, the good they do is inconceivable.

- This appears as an anonymous proverb in Frank Leslie's Sunday Magazine Vol. XIII, (January - June 1883) edited by T. De Witt Talmage, and apparently only in recent years has it become attributed to Addison.

- If men would consider not so much where they differ, as wherein they agree, there would be far less of uncharitableness and angry feeling in the world.

- Attributed to "Addison" in A Dictionary of Thoughts : Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, both Ancient and Modern (1908) edited by Tryon Edwards, p. 117, but this might be the later "Mr. Addison" who was credited with publishing Interesting Anecdotes, Memoirs, Allegories, Essays, and Poetical Fragments (1794).

- Tradition is an important help to history, but its statements should be carefully scrutinized before we rely on them.

- Attributed to "Addison" in A Dictionary of Thoughts : Being a Cyclopedia of Laconic Quotations from the Best Authors of the World, both Ancient and Modern (1908) edited by Tryon Edwards, p. 580, but this might be the later "Mr. Addison" who was credited with publishing Interesting Anecdotes, Memoirs, Allegories, Essays, and Poetical Fragments (1794).

- The greatest sweetener of human life is Friendship. To raise this to the highest pitch of enjoyment, is a secret which but few discover.

- As quoted in Hugs for Girlfriends : Stories, Sayings, and Scriptures to Encourage and Inspire (2001) by Philis Boultinghouse and LeAnn Weiss, p. 7; there seem to be no published sources available for this statement prior to 2001.

Misattributed

[edit]- Alphabetized by author

- A little nonsense now and then

Is relished by the wisest men.- This appears to be an anonymous proverb of unknown authorship, only occasionally attributed to Addison.

- With regard to donations always expect the most from prudent people, who keep their own accounts.

- This is attributed to Addison in The Columbia Dictionary of Quotations (1993) with a citation of "Economy and Benevolence" in Interesting Anecdotes, Memoirs, Allegories, Essays, and Poetical Fragments (1794) but that was a publication of a contemporary "Mr. Addison" in several volumes, and not the poet. Vol. III of that publication (in 1796), on page 205, does contain these lines, but as part of an anonymous ancecdote.

- Reading is a basic tool in the living of a good life.

- The earliest attributions of this remark to anyone are in 1941, to Mortimer Adler, in How To Read A Book (1940), although this actually a paraphrased shortening of a statement in his preface: Reading — as explained (and defended) in this book — is a basic tool in the living of a good life.

- When you are at Rome, live as Romans live.

- St. Ambrose, Si fueris Romæ, Romano vivito more as translated in Latin Proverbs and Quotations (1869) by Alfred Henderson; very commonly paraphrased as "When in Rome do as the Romans do".

- To say that authority, whether secular or religious, supplies no ground for morality is not to deny the obvious fact that it supplies a sanction.

- Sir Alfred Jules Ayer, in his "The Meaning of Life", collected in The Meaning of Life, and Other Essays (1990)

- There is not any present moment that is unconnected with some future one. The life of every man is a continued chain of incidents, each link of which hangs upon the former. The transition from cause to effect, from event to event, is often carried on by secret steps, which our foresight cannot divine, and our sagacity is unable to trace. Evil may at some future period bring forth good; and good may bring forth evil, both equally unexpected.

- Very often attributed to Addison, this is in fact by Hugh Blair, published in Blair's Sermons (1815), Vol. 1, pp. 196-197.

- To a man of pleasure every moment appears to be lost, which partakes not of the vivacity of amusement.

- Very often attributed to Addison, this is apparently a paraphrase of a statement by Hugh Blair, published in Blair's Sermons (1815), Vol. 1, p. 219, where he mentions "men of pleasure and the men of business", and that "To the former every moment appears to be lost, which partakes not of the vivacity of amusement".

- The grand essentials to happiness in this life are something to do, something to love and something to hope for.

- Widely quoted as an Addison maxim this is actually by the American clergyman George Washington Burnap (1802-1859), published in Burnap's The Sphere and Duties of Woman : A Course of Lectures (1848), Lecture IV.

- Justice is an unassailable fortress, built on the brow of a mountain which cannot be overthrown by the violence of torrents, nor demolished by the force of armies.

- Moncure Daniel Conway, in The Sacred Anthology (Oriental) : A Book of Ethnical Scriptures 5th edition (1877), p. 386; this statement appears beneath an Arabian proverb, and Upton Sinclair later attributed it to the Qur'an, in The Cry for Justice : An Anthology of the Literature of Social Protest (1915), p. 475.

- It is only imperfection that complains of what is imperfect. The more perfect we are the more gentle and quiet we become towards the defects of others.

- He that would pass the latter part of life with honour and decency, must, when he is young, consider that he shall one day be old; and remember, when he is old, that he has once been young.

- Samuel Johnson in The Rambler, no. 50 (8 September 1750); many of Johnson's remarks have been attributed to Addison

- No oppression is so heavy or lasting as that which is inflicted by the perversion and exorbitance of legal authority.

- Samuel Johnson in The Rambler, no. 148 (17 August 1751)

- That he delights in the misery of others no man will confess, and yet what other motive can make a father cruel?

- Samuel Johnson in The Rambler, no. 148 (17 August 1751)

- The unjustifiable severity of a parent is loaded with this aggravation, that those whom he injures are always in his sight.

- Samuel Johnson in The Rambler no. 148 (17 August 1751)

- Education...is a companion which no misfortunes can depress, no clime destroy, no enemy alienate, no despotism enslave: at home a friend, abroad an introduction, in solitude a solace, in society an ornament: it chastens vice, it guides virtue, it gives at once a grace and government to genius. Without it, what is man? A splendid slave, a reasoning savage.

- Though sometimes attributed to Addison, this actually comes from a speech delivered by the Irish lawyer Charles Phillips in 1817, in the case of O'Mullan v. M'Korkill, published in Irish Eloquence: The Speeches of the Celebrated Irish Orators (1834) pp. 91-92.

- They were a people so primitive they did not know how to get money, except by working for it.

- Attributed to Addison in (K)new Words: Redefine Your Communication (2005), by Gloria Pierre, p. 120, there are no indications of such a statement in Addison's writings.

- Plenty of people wish to become devout, but no one wishes to be humble.

- A translation of one of La Rochefoucauld's maxims, published posthumously in 1693. In the original: "Force gens veulent être dévots, mais personne ne veut être humble."

- The beloved of the Almighty are: the rich who have the humility of the poor, and the poor who have the magnanimity of the rich.

- Saadi as translated in The Gulistān : Or, Rose-garden, of Shek̲h̲ Muslihu'd-dīn Sādī of Shīrāz as translated by Edward Backhouse Eastwick (1880), p. 203

- Jesters do often prove prophets.

- Not found in Addison's works, and "Jesters do oft prove prophets" is actually William Shakespeare, in King Lear, Act V, sc. iii

- The utmost extent of man's knowledge, is to know that he knows nothing.

- These words, sometimes attributed to Addison, are not found in his works, but in The Spectator, no. 54, he translates the following words of Socrates, as quoted in Plato's Apology: "When I left him, I reasoned thus with myself: I am wiser than this man, for neither of us appears to know anything great and good; but he fancies he knows something, although he knows nothing; whereas I, as I do not know anything, so I do not fancy I do. In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know."

- The chief ingredients in the composition of those qualities that gain esteem and praise, are good nature, truth, good sense, and good breeding.

- William Temple, in "Heads Designed for an Essay on Conversation" in The Works of Sir William Temple, Bart. in Four Volumes (1757), Vol. III, p. 547

- The union of the Word and the Mind produces that mystery which is called Life... Learn deeply of the Mind and its mystery, for therein lies the secret of immortality.

- "The Life and Teachings of Thoth Hermes Trismegistus", in The Secret Teachings of All Ages (1928) by the Canadian occultist Manly Hall; a few quotation websites credit this to Addison.

Quotes about Addison

[edit]- In our way to the Club to-night, when I regretted that Goldsmith would, upon every occasion, endeavour to shine, by which he often exposed himself; Mr. Langton observed, that he was not like Addison, who was content with the fame of his writings, and did not aim also at excellency in conversation, for which he found himself unfit; and that he said to a lady, who complained of his having talked little in company, "Madam, I have but nine-pence in ready money, but I can draw for a thousand pounds".

- James Boswell, in The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791), mentioning a contrast made of Addison's character and that of Oliver Goldsmith, in his accounts of 7 May 1773

- The last place in London to which I will ask the reader to accompany me with Addison is one which has changed but little since his time, and has been of late very much in all our thoughts—I mean Westminster Abbey. He tells us that in his serious and pensive moods he very often walked there by himself, where the gloominess of the place, with the solemnity of the building, and the condition of the people who lie in it, filled his mind with a melancholy, or rather a thoughtfulness, that was not unpleasing.

- James G. Frazer (January 1922). "London Life in the Time of Addison". The Quarterly Review: 18–32. quote p. 32

- In the formal treatises Addison has three subjects: religion, classical literature, and Whig politics. His greatest delight in literature was the study of Latin poetry; and he was himself a most skilful writer of Latin verse—he is indeed more a poet in Latin than in English.

- A. C. Guthkelch "The Prose Works of Joseph Addison". The Quarterly Review 225: 238–250. January 1916, quote p. 242

- Whoever wishes to attain an English style, familiar, but not coarse, and elegant, but not ostentatious, must give his days and nights to the volumes of Addison.

- Samuel Johnson, Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1779-81), "Addison"

- As a man, he may not have deserved the adoration which he received from those who, bewitched by his fascinating society, and indebted for all the comforts of life to his generous and delicate friendship, worshipped him nightly, in his favourite temple at Button’s. But, after full inquiry and impartial reflection, we have long been convinced that he deserved as much love and esteem as can be justly claimed by any of our infirm and erring race. Some blemishes may undoubtedly be detected in his character; but the more carefully it is examined, the more it will appear, to use the phrase of the old anatomists, sound in the noble parts, free from all taint of perfidy, of cowardice, of cruelty, of ingratitude, of envy. Men may easily be named, in whom some particular good disposition has been more conspicuous than in Addison. But the just harmony of qualities, the exact temper between the stern and the humane virtues, the habitual observance of every law, not only of moral rectitude, but of moral grace and dignity, distinguish him from all men who have been tried by equally strong temptations, and about whose conduct we possess equally full information.

- Thomas Macaulay in "Essay on the Life and Writings of Addison", in Essays Vol. V (1866)

- Just men, by whom impartial laws were given;

And saints who taught and led the way to heaven.

Ne'er to these chambers, where the mighty rest,

Since their foundation came a nobler guest;

Nor e’er was to the bowers of bliss conveyed

A fairer spirit or more welcome shade.- Thomas Tickell, On the Death of Mr. Addison (1721)

- If in the stage I seek to soothe my care,

I meet his soul which breathes in Cato there;

If pensive to the rural shades I rove,

His shape o'ertakes me in the lonely grove;

'Twas there of just and good he reasoned strong,

Cleared some great truth, or raised some serious song:

There patient showed us the wise course to steer,

A candid censor, and a friend severe;

There taught us how to live; and (oh, too high

The price for knowledge!) taught us how to die.- Thomas Tickell, On the Death of Mr. Addison (1721)

- The prose of Whig and Tory polemics contained a larger proportion of stuff destined to endure: Swift and Addison,as journalists spoke to the their day but have been overheard by the ages.

- G. M. Trevelyan."England Under Queen Anne, Blenheim", Fontana Library,1965, Page 100

- The first English Writer who compos'd a regular Tragedy and infus'd a Spirit of Elegance thro' every Part of it, was the illustrious Mr. Addison. His CATO is a Master-piece both with regard to the Diction, and to the Beauty and Harmony of the Numbers. The Character of Cato is, in my Opinion, vastly superiour to that of Cornelia in the POMPEY of Corneille: For Cato is great without any Thing like Fustian, and Cornelia, who besides is not a necessary Character, tends sometimes to bombast. Mr. Addison's Cato appears to me the greatest Character that was ever brought upon any Stage, but then the rest of them don't correspond to the Dignity of it: And this dramatic Piece so excellently well writ, is disfigur'd by a dull Love Plot, which spreads a certain Languor over the whole, that quite murders it.

- Voltaire, Letters Concerning the English Nation (1733), pp. 178-179

- He dismissed his physicians, and with them all hopes of life. But with his hopes of life he dismissed not his concern for the living, but sent for a youth nearly related and finely accomplished, but not above being the better for good impressions from a dying friend. He came; but, life now glimmering in the socket, the dying friend was silent. After a decent and proper pause, the youth said, "Dear sir, you sent for me: I believe and I hope that you have some commands; I shall hold them most sacred." May distant ages not only hear, but feel, the reply! Forcibly grasping the youth's hand, he softly said, "See in what peace a Christian can die!" He spoke with difficulty and soon expired. Through grace Divine, how great is man!