Journey to the West

Appearance

Heaven will grant him support.

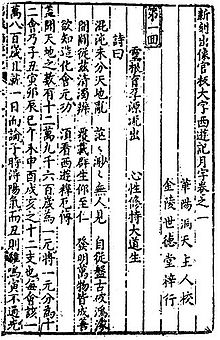

Journey to the West is a Chinese novel published in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty and attributed to Wu Cheng'en. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature.

Quotations

[edit]- The Journey to the West, trans. and ed. Anthony C. Yu, 4 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1983)

- 灵根育孕源流出,心性修持大道生。

- The divine root conceives, its source revealed;

Mind and nature nurtured, the Great Dao is born.- Chapter 1

- The divine root conceives, its source revealed;

- Since the creation of the world, [an immortal stone] had been nourished for a long period by the seeds of Heaven and Earth and by the essences of the sun and the moon, until, quickened by divine inspiration, it became pregnant with a divine embryo. One day, it split open, giving birth to a stone egg about the size of a playing ball. Exposed to the wind, it was transformed into a stone monkey endowed with fully developed features and limbs.

- Chapter 1

- 日映岚光轻锁翠,雨收黛色冷含青。

- The sun's beams lightly enclose the azure mist;

In darkening rain, the mount's color turns cool and green.- Chapter 1

- The sun's beams lightly enclose the azure mist;

- "Can this sort of practice lead to immortality?" asked Wukong. "Impossible! Impossible!" said the Patriarch. "I won't learn it then," Wukong said.

- Chapter 2

- "To obtain immortality from such activities," said the Patriarch, "is also like scooping the moon from the water." "There you go again, Master!" cried Wukong. "What do you mean by scooping the moon from the water?" The Patriarch said, "When the moon is high in the sky, its reflection is in the water. Although it is visible therein, you cannot scoop it out or catch hold of it, for it is but an illusion."

- Chapter 2

- "Nothing in the world is difficult," said the Patriarch; "only the mind makes it so."

- Chapter 2

- "You senseless pi-ma-wên! You are guilty of the ten evils. You first stole peaches and then wine, utterly disrupting the Grand Festival of Immortal Peaches. You also robbed Laozi of his immortal elixir, and then you had the gall to plunder the imperial winery for your personal enjoyment. Don't you realize that you have piled up sin upon sin?" "Indeed," said the Great Sage, "these several incidents did occur! But what do you intend to do now?"

- Chapter 5

- Your Majesty, what ability and what virtue does your poor monk possess that he should merit such affection from your Heavenly Grace? I shall not spare myself in this journey, but I shall proceed with all diligence until I reach the Western Heaven. If I do not attain my goal, or the true scriptures, I shall not return to our land even if I have to die. I would rather fall into eternal perdition in Hell.

- Spoken by Xuanzang in chapter 12

- Treasure a handful of dirt from your home,

But love not ten thousand taels of foreign gold.- Spoken by Taizong in chapter 12

- 心生,种种魔生;心灭,种种魔灭。

- When the mind is active all kinds of māra [demons] come into existence; when the mind is extinguished, all kinds of māra will be extinguished.

- Spoken by Xuanzang in chapter 13

- When the mind is active all kinds of māra [demons] come into existence; when the mind is extinguished, all kinds of māra will be extinguished.

- "You may proceed now, Master. Those robbers have been exterminated by old Monkey."

"That's a terrible thing you have done!" said Tripitaka. "...If you have such abilities, you should have chased them away. Why did you slay them all? How can you be a monk when you take life without cause? ... You showed no mercy at all! ..."

"Master," said Wukong, "if I hadn't killed them, they would have killed you!" Tripitaka said, "As a priest, I would rather die than practice violence."- Chapter 14

- 唐僧道:“悟空,你说得几时方可到?”行者道:“你自小时走到老,老了再小,老小千番也还难。只要你见性志诚,念念回首处,即是灵山。”

- "Wukong," said the Tang Monk, "tell us when we shall be able to reach our destination."

Pilgrim said, "You can walk from the time of your youth till the time you grow old, and after that, till you become youthful again; and even after going through such a cycle a thousand times, you may still find it difficult to reach the place you want to go to. But when you perceive, by the resoluteness of your will, the Buddha-nature in all things, and when every one of your thoughts goes back to its very source in your memory, that will be the time you arrive at the Spirit Mountain."- Chapter 24

- "Wukong," said the Tang Monk, "tell us when we shall be able to reach our destination."

- I was born with a laughing face!

- Spoken by Wukong in chapter 25

- Pilgrim said to them, "Now leave the hall and close the shutters so that the Heavenly mysteries will not be seen by profane eyes. We shall leave you some holy water." The Daoists retreated from the hall and closed the doors.... Pilgrim stood up at once and, lifting up his tiger-skin kilt, filled the flowerpot with his stinking urine. Delighted by what he saw, Zhu Eight Rules said, "Elder Brother, you and I have been brothers these few years but we have never had fun like this before. Since I gorged myself just now, I have been feeling the urge to do this." Lifting up his clothes, our Idiot...pissed till he filled the whole garden vase. Sha Monk, too, left behind half a cistern. They then straightened their clothes and resumed their seats solemnly before they called out, "Little ones, receive your holy water." Pushing open the shutters, those Daoists kowtowed repeatedly to give thanks. They carried the cistern out first, and then they poured the contents of the vase and the pot into the bigger vessel, mixing the liquids together. "Disciples," said the Tiger-Strength Immortal, "bring me a cup so that I can have a taste." A young Daoist immediately fetched a teacup and handed it to the old Daoist. After bailing out a cup of it and gulping down a huge mouthful, the old Daoist kept wiping his mouth and puckering his lips. "Elder Brother," said the Deer-Strength Immortal, "is it good?" "Not very good," said the old Daoist, his lips still pouted, "the flavor is quite potent!" "Let me try it also," said the Goat-Strength Immortal, and he, too, downed a mouthful. Immediately he said, "It smells somewhat like hog urine!"

- Chapter 45

- 山高自有客行路,水深自有渡船人。

- The tall mountains will have their passageways;

The deep waters will have their ferry boats.- Proverb quoted by Wukong in chapter 74

- The tall mountains will have their passageways;

- Seek not afar for Buddha on Spirit Mount;

Mount Spirit lives only inside your mind.- Heart Sūtra quoted by Wukong in chapter 85

- The lesson of all scriptures concerns only the cultivation of the mind.

- Spoken by Xuanzang in chapter 85

- When the mind is pure, it shines forth as a solitary lamp, and when the mind is secure, the entire phenomenal world becomes clarified.

- Spoken by Wukong in chapter 85

- To serve the ruler or to serve one's parents follows the same principle. You live by the kindness of your parents, and I do by the kindness of my ruler.

- Spoken by Xuanzang in chapter 85

- When man has a virtuous thought,

Heaven will grant him support.- Chapter 87

- 人心生一念,天地悉皆知。善恶若无报,乾坤必有私。

- One wish born in the heart of man

Is known throughout Heaven and Earth.

If vice or virtue lacks reward,

Unjust must be the universe.- Chapter 87

- One wish born in the heart of man

- "Sage Monk, having come all this distance from the Land of the East, what sort of small gifts have you brought for us? Take them out quickly! We'll be pleased to hand over the scriptures to you."

On hearing this, Tripitaka said, "Because of the great distance, your disciple, Xuanzang, has not been able to make such preparation."

"How nice! How nice!" said the two Honored Ones, snickering. "If we imparted the scriptures to you gratis, our posterity would starve to death!"- Chapter 98

- When Sha Monk opened up a scroll of scripture that the other two disciples were clutching, his eyes perceived only snow-white paper without a trace of so much as half a letter on it. Hurriedly he presented it to Tripitaka, saying, "Master, this scroll is wordless!" Pilgrim also opened a scroll and it, too, was wordless. Then Eight Rules opened still another scroll, and it was also wordless. "Open all of them!" cried Tripitaka. Every scroll had only blank paper.

- Chapter 98

- What good is it to take back a wordless, empty volume like this? How could I possibly face the Tang emperor? The crime of mocking one's ruler is greater than one punishable by execution!

- Spoken by Xuanzang in chapter 98

- These blank texts are actually true, wordless scriptures, and they are just as good as those with words. However, those creatures in your Land of the East are so foolish and unenlightened that I have no choice but to impart to you now the texts with words.

- Spoken by Tathāgata in chapter 98

Quotations about Journey to the West

[edit]

~ Lin Yutang

~ Arthur Waley

- With his sense of the ridiculous anchored in the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness, therefore, the author mocks all the monsters as he mocks all the pilgrims and celestials in the book. Not only is everything infinitely amusing to his observant eye, but in the ultimate religious sense everything that exists is but maya [illusion] with which we are infatuated. Even the most serious character and the one nearest to approaching an understanding of emptiness, Monkey himself, is not spared this affectionate ridicule. To readers conditioned to accept the reality of literary fiction, this attempt at constant negation can be at times very unsettling. Writing from the Christian viewpoint which accords reality to every soul be it suffering eternal damnation in hell or rejoicing in eternal bliss in paradise, Dante has created a massive comedy of substantial reality designed to elicit our strongest emotional responses. Wu Ch'eng-en, on the other hand, provides in episode after comic episode the illusion of mythical reality, but then inevitably exposes the falsehood of that reality in furtherance of his Buddhist comedy.

- C. T. Hsia, The Classic Chinese Novel: A Critical Introduction (1968), pp. 147–148

- Freed from all kinds of allegorical interpretations by Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucianist commentators, Monkey is simply a book of good humor, profound nonsense, good-natured satire and delightful entertainment.

- Hu Shih, foreword to Arthur Waley's translation (1942), p. 5

- [Journey to the West] describes the exploits and adventures of the monk Hsüantsang in his pilgrimage to India, in the company of three extremely lovable semi-human beings, Sun the Monkey, Ghu the Pig, and the Monk Sand. It is not an original creation, but is based on a religious folk legend. The most lovable and popular character is of course Sun the Monkey, who represents the mischievous human spirit, eternally aiming at the impossible. He ate the forbidden peach in heaven as Eve ate the forbidden apple in Eden, and he was finally chained under a rock for five hundred years as Prometheus was chained. By the time the decreed period was over, Hsüantsang came and released him, and he was to undertake the journey, fighting all the devils and strange creatures on the way, as an atonement for his sins, but his mischievous spirit always remained, and his development represents a struggle between the unruly human spirit and the holy way. He had on his head an iron crown, and whenever he committed a transgression, Hsüantsang's incantation would cause the crown to press on his head until his head was ready to burst with pain. At the same time Ghu the Pig represents the animal desires of men, which are gradually chastened by religious experience. The conflict of such desires and temptations in a highly strange journey undertaken by a company of such imperfect and highly human characters produces a continual series of comical situations and exciting battles, aided by supernatural weapons and magic powers. Sun the Monkey had stuck away in his ear a wand which could at will be transformed into any length he desired, and, moreover, he had the ability to pull out hairs on his monkey legs and transform them into any number of small monkeys to harass his enemies, and he could change himself into a cormorant or a sparrow or a fish or a temple, with the windows for his eyes, the door for his mouth and the idol for his tongue, ready to gobble up the hostile monster in case he should cross the threshold of the temple. Such a fight between Sun the Monkey and a supernatural spirit, both capable of changing themselves, chasing each other in the air, on earth, and in the water, should not fail to interest any children or grown-ups who are not too old to enjoy Mickey Mouse.

- Lin Yutang, My Country and My People (1935), pp. 276–277

- I come more and more to appreciate the wisdom and insight of the great Chinese monkey epic, Hsiyuchi. The progress of human history can be better understood from this point of view; it is so similar to the pilgrimage of those imperfect, semi-human creatures to the Western Heaven—the Monkey Wuk'ung representing the human intellect, the Pig Pachieh representing our lower nature, Monk Sand representing common sense, and the Abbot Hsüantsang representing wisdom and the Holy Way. The Abbot, protected by this curious escort, was engaged upon a journey from China to India to procure sacred Buddhist books. The story of human progress is essentially like the pilgrimage of this variegated company of highly imperfect creatures, continually landing in dangers and ludicrous situations through their own folly and mischief. ... The instincts of human frailty, of anger, revenge, impetuousness, sensuality, lack of forgiveness, above all self-conceit and lack of humility, forever crop up during this pilgrimage of mankind toward sainthood.

- Lin Yutang, The Importance Of Living (1937), Ch. 3: "Our Animal Heritage", I. The Monkey Epic, pp. 33–34

- The Monkey was clever, but he was also conceited; he had enough monkey magic to push his way into Heaven, but he had not enough sanity and balance and temperance of spirit to live peacefully there. ... [He] set up a banner of rebellion against Heaven, writing on it the words "The Great Sage, Equal of Heaven." There followed then terrific combats between this Monkey and the heavenly warriors, in which the Monkey was not captured until the Goddess of Mercy knocked him down with a gentle sprig of flowers from the clouds. So, like the Monkey, forever we rebel and there will be no peace and humility in us until we are vanquished by the Goddess of Mercy, whose gentle flowers dropped from Heaven will knock us off our feet.

- Lin Yutang, The Importance Of Living (1937), pp. 34–35

- [Monkey] had to learn the lesson of humility by an ultimate bet with Buddha or God Himself. He made a bet that with his magical powers he could go as far as the end of the earth, and the stake was the title of "The Great Sage, Equal of Heaven," or else complete submission. Then he leaped into the air, and traveled with lightning speed across the continents until he came to a mountain with five peaks, which he thought must be as far as mortal beings had ever set foot. In order to leave a record of his having reached the place, he passed some monkey urine at the foot of the middle peak, and having satisfied himself with this feat, he came back and told Buddha about his journey. Buddha then opened one hand and asked him to smell his own urine at the base of the middle finger, and told him how all this time he had never left the palm.

- Lin Yutang, The Importance Of Living (1937), p. 35

- This Monkey, which is an image of ourselves, is an extremely lovable creature, in spite of his conceit and his mischief. So should we, too, be able to love humanity in spite of all its weaknesses and shortcomings.

- Lin Yutang, The Importance Of Living (1937), p. 36

- So then, instead of holding on to the Biblical view that we are made in the image of God, we come to realize that we are made in the image of the monkey.

- Lin Yutang, The Importance Of Living (1937), p. 36

- Although Wu Cheng-en was a Confucian scholar, he wrote this book for entertainment. ... If we insist on seeking some hidden meaning, the following comment by Hsieh Chao-chih is quite adequate: "The Pilgrimage to the West is purely imaginary, belonging to the realm of fantasy and miraculous transformations. Monkey symbolizes man's intelligence, Pigsy man's physical desires. Thus Monkey first runs wild in heaven and on earth, proving quite irrepressible; but once he is kept in check he steadies down. So this is an allegory of the human mind, not simply a fantasy."

- Lu Hsun, A Brief History of Chinese Fiction (1982), pp. 206–207

- Monkey is unique in its combination of beauty with absurdity, of profundity with nonsense. Folk-lore, allegory, religion, history, anti-bureaucratic satire and pure poetry—such are the singularly diverse elements out of which the book is compounded.

- Arthur Waley, Preface to Monkey (1942), p. 9

- As regards the allegory, it is clear that Tripitaka stands for the ordinary man, blundering anxiously through the difficulties of life, while Monkey stands for the restless instability of genius. Pigsy, again, obviously symbolizes the physical appetites, brute strength, and a kind of cumbrous patience. Sandy is more mysterious. The commentators say that he represents ch'êng, which is usually translated 'sincerity', but means something more like 'whole-heartedness'.

- Arthur Waley, Preface to Monkey (1942), p. 10

In fiction

[edit]- It was time to talk about choosing the plays and Grandmother Jia called on Bao-chai to begin. Bao-chai made a show of declining; but it was her birthday, and in the end she gave in and selected a piece about Monkey from The Journey to the West. Grandmother Jia was pleased.

- Cao Xueqin, Dream of the Red Chamber (c. 1760), Ch. 22, as translated by David Hawkes in The Story of the Stone: The Golden Days (1973), p. 434

External links

[edit] Encyclopedic article on Journey to the West on Wikipedia

Encyclopedic article on Journey to the West on Wikipedia- "The Stone Monkey", from Herbert Giles's Chinese Fairy Tales, at Wikisource

- Journey to the West (PDF) — Teaching Guide, at UW-Madison Center for the Humanities

- Journey to the West (Video Transcript) — Invitation to World Literature, at Annenberg Learner