Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Appearance

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Quotes

[edit]- Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

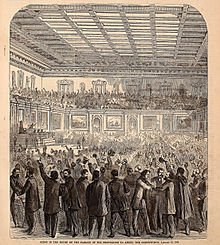

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.- 13th amendment, passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and ratified on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18.

About Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

[edit]- At the end of the Civil War slavery was for the first time authorized by the US Constitution in the 13th Amendment, which authorized the government to treat convicts as slaves. So the newly “freed” Blacks were simply targeted with criminal prosecutions and then placed right back into bondage to serve as contract laborers, on chain gangs, and on prison plantations.

- Kevin Rashid Johnson, "Amerikan Prisons Are Government-Sponsored Torture," Socialism and Democracy, vol. 21, no. 1 (2007), p. 87

Amicus Curiae Brief in Support of Jane Roe California Committee to Legalize Abortion; South Bay Chapter of the National Organization for Women; Zero Population Growth, Inc.; Cheriel Moench Jensen; and Lynette Perkes

[edit]Filed by Joan K. Bradford, Esq.; as quoted in “Before Roe v. Wade” by Linda Greenhouse and Reva B. Siegel, Yale Law School, 2012

- Each of the organizations and individuals urges upon the Court the position that laws restricting or regulating abortion as a special procedure violate the Thirteenth Amendment by imposing involuntary servitude without due conviction for a crime and without the justification of serving any current national or public need....

- p.341

- From the outset, the Amendment has been interpreted by this Court to apply to all persons without regard to race or class, and to guarantee universal freedom in the United States....

It is the purpose of this brief to show that anti-abortion laws, which force an unwillingly pregnant woman to continue pregnancy to term, are a form of involuntary servitude without the justification of serving any current national or public need.- p.342

- The women who bear children and the medical experts who assist them testify that pregnancy and childbearing are indeed labor. The fact that many women enter into such labor voluntarily and joyfully does not alter the fact that other women, under other circumstances, find childbearing too arduous, become pregnant through no choice of their own, and are then forced to complete the pregnancy to term by compulsion of state laws prohibiting voluntary abortion. It is the purpose of the Thirteenth Amendment to prohibit a relationship in which one person or entity limits the freedom of another person. In the absence of a compelling state interest or due conviction for a crime, the state’s forcing the pregnant woman through unwanted pregnancy to full term is a denial of her Thirteenth Amendment right to be free from “a condition of enforced compulsory service of one to another.” This is the very essence of involuntary servitude in which the personal service of one person is “disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit.”

- pp.344-345

- The Thirteenth Amendment’s promise of freedom has long provided to male citizens the sovereign control of their own bodies.

- p.346

"Forced Labor: A Thirteenth Amendment Defense of Abortion" (1990)

[edit]Andrew Koppelman, "Forced Labor: A Thirteenth Amendment Defense of Abortion", Northwestern Law Review, Vol. 84, (1990)

- When women are compelled to carry and bear children, they are subjected to “involuntary servitude” in violation of the thirteenth amendment. Abortion prohibitions violate the amendment’s guarantee of personal liberty, because forced pregnancy and childbirth, by compelling the woman to serve the fetus, created “that control by which the personal service of one man [sic] is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit which is the essence of involuntary servitude.” Such laws violate the amendment’s guarantee of equality, because forcing women to be mothers makes them into a servant caste, a group which, bu virtue of status of birth, is held subject to a special duty to serve others and not themselves.

This argument makes available two responses to the objection that the fetus is a person. The first is that,even if this is so, the fetus’ right to continued aid from the woman does not automatically follow. As Thomson observed, “having a right to life does not guarantee having either a right to be given the use of or a right to be allowed continued use of another person’s body-even if one needs it for life itself.” Quite the reverse, giving fetuses a legal right to the continued use of their mothers’ bodies would be precisely what the thirteenth amendment forbids. The second response is that since abortion prohibitions infringe on the fundamental right to be free of involuntary servitude, the state bears the burden of having to show that the violation of this right is justified. The state cannot carry this burden, because no one knows how to prove (or disprove) that a fetus is, or should be considered, a person. The mere possibility that it “might” be is not enough to justify violating women’s Thirteenth Amendment rights by forcing them to be mothers.- pp.484-485.

- The idea of self-ownership is inextricably linked with our society’s ideals of individual worth and dignity To give control of even part of my body to someone else is to treat me as property, as as thing rather than a person. The right not to have one’s body controlled by others is inalienable, for two reasons: first, because agreements to abandon one’s freedom are likely to be made in coercive circumstances in which consent is illusory, and second, because to enforce such agreements tends to place the state’s imprimatur on relations of caste domination and subjection. All of these concerns are applicable to women with unwanted pregnancies, whose “consent” to their condition is usually equally illusory. Laws against abortion define women as a servant caste and enforce that definition with criminal sanctions. This is the same kind of injury that antebellum slavery inflicted on blacks, and it therefore violates women’s thirteenth amendment rights.

- p.485.

- Most of the jurisprudence surrounding the thirteenth amendment concerns Congress’ power under the second section, but this essay will focus on the first, which is self-executing. Although primarily directed against the slavery of the antebellum South, the amendment is broader in scope, as the Court held when it first considered the amendment in the Slaughter House Cases:

Undoubtedly while negro slavery alone was in the mind of the Congress which proposed the thirteenth article, it any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter If Mexican peonage or the Chinese coolie labor system shall develop slavery of the Mexican or Chinese race within our territory, this amendment may safely be trusted to make it void.

The Court also said that “the word servitude is or larger meaning than slavery, as the latter is popularly understood in this country . . . . It was very well understood that . . . the purpose of the article might have been evaded, if only the word slavery had been used.” Later cases explain more specifically what “involuntary servitude” encompassed: “the control of the labor and services of one man for the benefit of another, and the absence of a legal right to the disposal of his own person, property and “services”; “a condition of enforced compulsory service of one to another,” ”that control by which the personal service of one man is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit which is the essence of involuntary servitude.”- p.486-487

- Bailey’s definition of involuntary servitude as “that control by which the personal service of one man is disposed of or coerced for another’s benefit” encompasses the burden imposed on women by laws against abortion, since the “natural operation” of a statute prohibiting abortion is to make it a crime for a woman to refuse to render service to a fetus. Even had the decision been differently worded, any decision in Bailey’s favor would probably protect the woman who seeks to abort, since the servitude to which Bailey was subjected was considerably less-less taxing, less intrusive, and less total in its probable impact on the course of his whole life-than that which forced pregnancy imposes on her.

Bailey also provides an answer to those who would dispute that the servitude is involuntary. As I noted earlier, some opponents to abortion think that women should be considered to assume the risk of pregnancy when they consent to have sex. This argument is far-fetched, but even if women did deliberately assume such a risk, Bailey holds that the right to personal liberty guaranteed by the thirteenth amendment is inalienable.

The full intent of the constitutional provision could be defeated with obvious facility if, through the guise of contracts under which advances had been made, debtors could be held to compulsory service. It is the compulsion of the service that the statute which enforces the amendment inhibits, for when that occurs the condition of servitude is created, which would not be less involuntary because of the original agreement to work out the indebtedness.- p.491

- Bailey’s libertarian reading go the amendment, in which the right to freedom outweighs any other consideration, may seem unsatisfying, both morally and as an account of the amendment’s purpose. Its vision of society may appear more harmonious with the constitutionalization of laissez-faire individualism in Lochner v. New York, decided six years before Bailey, than with modern sensibilities. The modern administrative state needs to interfere with traditional individual liberties in myriad ways, some of them vitally linked to the promotion of women’s equality. This way be why, when an amicus in Roe relied on Bailey’s libertarianism to argue for a thirteenth amendment right to abortion, the Court expressly rejected the view “that one has an unlimited right to do with one’s body as one pleases”

The liberty guaranteed by the thirteenth amendment, however, is narrower than this. It is not quite correct t say that the thirteenth amendment protects one’s right to control one’s own body. More precisely, the liberty the thirteenth amendment guarantees is the liberty not to have one’s body controlled by and for others.- pp.493-494

- Even if the amendment guarantees self-ownership, why can I not contract my self-ownership away? Alienability is after all one of the rights normally associated with ownership. Inasmuch as I am not permitted to sell myself, it may be argued that I am not fully the owner of myself. Nozick, for example, thinks that a free system would allow a person to sell himself into slavery.

To explain Bailey’s rule of inalienability, it is necessary to look beyond libertarian individualism and consider broader social inequalities. Such inequalities are part of the concern of a constitutional provision designed to eradicate slavery, because slavery did more than compel some individuals to serve the private interests of others: that burden was placed on a determinate social caste. 65 The framers believed that he work of abolition was only half complete as long as blacks remained legally inferior to whites, and they were right. Ass development in the South after the Civil War brutally demonstrated, pervasive inequalities make it possible for some citizens to subjugate others in ways that resemble antebellum slavery all too well.- p.495-496

- There are two explanations for Bailey’s inalienability rule. The first is prophylactic: the rule prevents enforcement of ersatz contracts to which, because made in coercive circumstances, there was never real consent. The second is symbolic: by following the rule, the state refuses to give its sanction to the subjection of one class of citizens to another.

Most economic analysts favor the first explanation. They have found inalienability to be problematic on its face, because this kind of paternalistic restraint may actually harm those it purports to help. That was the argument of the dissenting opinion in Bailey, in which Justice Holmes declared that he “cannot believe” that the amendment prohibits a statute which “punishes the mere refusal to labor according to contract as a crime.”

The Thirteenth Amendment does not outlaw contracts for labor. That would be at least as great a misfortune for the laborer as for the man that employed him. For it certainly would affect the terms of the bargain if it were understood that the employer could do nothing in case the laborer saw fit to break his word.- p.496

- The importance to thirteenth amendment jurisprudence of this concern about invidious social meanings is most evident in the Court’s interpretation of the second section of the amendment, which provides that “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” This provision, the Court has held, “authorizes Congress not only to outlaw all forms of slavery and involuntary servitude but also to eradicate the last vestiges and incidents of a society half slave and half free. . . .” On the basis of this interpretation, the Court in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. sustained Congress’ authority to outlaw private racial discrimination: “Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment to determine what are the badges and incident of slavery, and the authority to translate that determination into effective legislation.” Tribe thinks that this language, if read literally, grants to Congress a power to protect individual rights “which is as open-ended as its power to regulate interstate commerce.” But unlike the thirteenth amendment, the commerce clause does not specify the evil which Congress is empowered to eliminate. If the thirteenth amendment authorizes congress to eradicate the badges of slavery-even those which, as in Jones, do not directly impose involuntary servitude-this can only be because they, too, are among the evils that the amendment forbids.

- pp.498-499

- The thirteenth amendment is both libertarian and egalitarian, because the paradigmatic violation, antebellum slavery, deprives its victims of both liberty and equality. It compelled some private individuals to serve others, and it did so as part of a larger societal pattern of imposing such servitude on a particular caste of persons. If the libertarian and egalitarian rules of decision are both plausible readings of the amendment, it is because each stresses one undeniable aspect of the paradigmatic case. Th Court may invalidate laws that impose servitude only on individuals, as it said it was doing in Bailey, and Congress may outlaw practices that stigmatize, but do no more than stigmatize, traditionally subjugated groups, as in Jones. But if either of these cases were paradigmatic of the amendment reaches far enough to forbid either of these injuries standing alone, a fortiori it forbids practices that inflict both of them at once. Compulsory pregnancy is such a practice.

- p.503

- There is, however, a single Supreme Court decision which announces an exception to the thirteenth amendment broad enough to accommodate forced childbearing. In Robertson v. Baldwin, a divided Court upheld against a thirteenth amendment challenge a statute authorizing the forcible return of deserting seamen to their vessels. The exception to the amendment carved out in Robertson is far broader than that of the alter conscription cases. But, as I will explain, Robertson is no longer good law.

Justice Brown, writing for the Court, relied on four arguments.

First, he held that “involuntary servitude” does not include any servitude entered into voluntarily, and that “an individual may, for a valuable consideration, contract for the surrender of his personal liberty for a definite time and for a recognized purpose, and subordinate his going and coming to the will of another during the continuance of the contract;not that all such contracts would be lawful, but that a servitude which was knowingly and willingly entered into could not be termed involuntary.” This might be construed to encompass pregnancy, at least in cases in which the woman freely consented to sex and thus, some will say, voluntarily undertook the risk of conception. For all the reason enumerated earlier, this voluntariness is often suspect, but since Brown abjured a blanket inalienability rule, his reasoning might permit the state to demand that women prove this on a case-by-case basis.

Second, he held that “the amendment was not intended to introduce any novel doctrine with respect to certain descriptions of service which have always been treated as exceptional; such as military and naval enlistments,” and concluded that “services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional shall not be regarded as within its purview.” A woman’s duty to bear children might be characterize as such an exceptional service, although this cannot easily be reconciled with the fourteenth amendment cases noted above.

Third, Justice Brown argued that such exceptions should be recognized as “arising from the necessities of the case.” Unlike the conscription cases, however, the necessity that Brown deemed sufficient to justify the imposition was private need, not danger to the polity. The risk that deserting sailors pose to a ship is, of course, considerably less than the danger that abortion poses to a fetus.

Fourth, he observed that Congress had made “very careful provisions. . . for the protection of seamen . . . as far as possible, against the consequences of their own ignorance and improvidence,” and concluded that “seamen are treated by Congress . . . as deficient in that full and intelligent responsibility for their acts which is accredited to ordinary adults, as needing the protection of the law . . . .” So much for compulsory service being an honorable badge of citizenship. This rather seems analogous to the common law’s traditional treatment of women as incompetents.- pp.523-525

- Robertson, more than any other Supreme Court decision, supports the view that the thirteenth amendment does not prohibit forced childbearing. But later cases have invalidated all four of Robertson’s arguments. The peonage cases squarely hold that a state “may not directly or indirectly command involuntary servitude, even if it was voluntarily contracted for.” As for “services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional,” both the Supreme Court and the lower courts have largely neglected this phrase, probably because it simply makes no sense; how can there be an exception that antedates the rule?197 The public necessity requirement seems to have been considerably tightened in Butler and Jacobson. And we know that has become of the idea that women are incompetents who may therefore properly be subjected to the absolute authority of their fathers and husbands.

The sounder view would seem to be that of the dissenting Justice Harlan, who called the Court’s decision “judicial legislation” and concluded that “[a] condition of enforced service, even for a limited period, in the private service of another, is a condition of involuntary servitude.” Here, as in another, better known Civil War amendments case, Harlan’s lone dissent seems to have prevailed over brown’s majority opinion. Robertson, although it has never expressly been overruled, stands as a decision whose rationale has evaporated from under it.- pp.525-526

- Even if the thirteenth amendment provides textual support for Roe’s holding, what, if anything, has it to say about the jurisprudence of the abortion cases that followed Roe?

To begin with, there is one kind of case in which the thirteenth amendment argument is simply overpowering. A demand by the father that the pregnancy continue, however deeply he might desire to procreate, would be a request that another person’s body be placed at his disposal for his purposes. A law giving the gather of the fetus the right to veto an abortion would represent the easiest thirteenth amendment case of all.- pp.526-527