Frederick Douglass: Difference between revisions

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

Content deleted Content added

→1880s: merging. |

→Quotes about Douglass: +quote. |

||

| Line 482: | Line 482: | ||

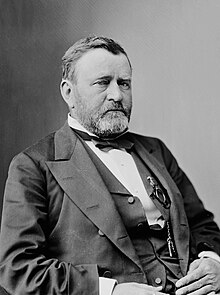

*In contrast to the contemporary black Americans, the black Americans, in that era, were in solid support of the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]. This was the party that fought the northern and southern Democrats to pass the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. '''Although President [[Andrew Johnson]] tried to bamboozle Frederick Douglass to the Democrat side by making false or empty promises, he did not succeed. Douglass was no fool and was not going to let Johnson use him to gain the support of the Negroes in his effort to be 'elected' president.''' Frederick Douglass and other prominent Blacks threw their support to [[Ulysses S. Grant]] for president. |

*In contrast to the contemporary black Americans, the black Americans, in that era, were in solid support of the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]. This was the party that fought the northern and southern Democrats to pass the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. '''Although President [[Andrew Johnson]] tried to bamboozle Frederick Douglass to the Democrat side by making false or empty promises, he did not succeed. Douglass was no fool and was not going to let Johnson use him to gain the support of the Negroes in his effort to be 'elected' president.''' Frederick Douglass and other prominent Blacks threw their support to [[Ulysses S. Grant]] for president. |

||

**[[w:Connie A. Miller, Sr.|Connie A. Miller, Sr.]], [http://books.google.com/books?id=9ykO8sKDE30C&pg=PA276&lpg=PA276&dq=%22I+know+the+man.+I+like+a+man+in+the+Presidential+chair%22&source=bl&ots=0JRNsxNa8j&sig=UJpkupLqhe7-DOrhKxCYSCo7EcY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FA9lU5z5JsnQsQTM1YH4CA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22I%20know%20the%20man.%20I%20like%20a%20man%20in%20the%20Presidential%20chair%22&f=false ''Frederick Douglass: American Hero''] (2008), p. 276. |

**[[w:Connie A. Miller, Sr.|Connie A. Miller, Sr.]], [http://books.google.com/books?id=9ykO8sKDE30C&pg=PA276&lpg=PA276&dq=%22I+know+the+man.+I+like+a+man+in+the+Presidential+chair%22&source=bl&ots=0JRNsxNa8j&sig=UJpkupLqhe7-DOrhKxCYSCo7EcY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FA9lU5z5JsnQsQTM1YH4CA&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=%22I%20know%20the%20man.%20I%20like%20a%20man%20in%20the%20Presidential%20chair%22&f=false ''Frederick Douglass: American Hero''] (2008), p. 276. |

||

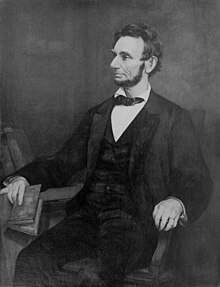

* Frederick Douglass was one of the foremost leaders of the abolitionist movement which fought to end slavery within the United States in the decades prior to the Civil War. He eagerly attended the founding meeting of the republican party in 1854 and campaigned for its nominees. A brilliant speaker, Douglass was asked by the American Anti-Slavery Society to engage in a tour of lectures, and so became recognized as one of America's first great black speakers. He won world fame when his autobiography The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, in which he gave specific details of his bondage, was publicized in 1845. Two years later, he began publishing an anti-slavery paper called the North Star. He was appointed Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti by President Benjamin Harrison on July 1, 1889, the first black citizen to hold high rank in the U.S. government. Douglass served as an adviser to President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War and fought for the adoption of constitutional amendments that guaranteed voting rights and other civil liberties for blacks. After the Civil War, Douglass realized that the war for citizenship had just begun when Democrat President Andrew Johnson proved to be a determined opponent of land redistribution and civil and political rights for former slaves. Douglass began the postwar era relying on the same themes that he preached in the antebellum years: economic self-reliance, political agitation, and coalition building. Douglass provided a powerful voice for human rights during this period of American history and is still revered today for his contributions against racial injustice. |

|||

**[[w:National Black Republican Association|National Black Republican Association]], [http://www.nationalblackrepublicans.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=pages.blackgop& "Frederick Douglass (1817–1895)"] (2009), ''Black Republican History'', National Black Republican Association. |

|||

*'''If our moral duty is to come to the aid of victims of criminal assault, if we are able to do so, then the moral duty of northerners was to come to the aid immediately of enslaved human beings in the south, just as [[John Brown (abolitionist)|John Brown]] and [[w:Frederick Douglass|Frederick Douglass]] originally thought.''' But if it was the duty of true abolitionists to take up arms, it would be perverse not to do so just because the political rationale at large was otherwise somewhat morally confused. Thus, '''even if other northerners fought to 'save the Union' rather than to free the slaves, that could have been accepted, as it was by Douglass, as sufficient for the commission of the proper purpose.''' |

*'''If our moral duty is to come to the aid of victims of criminal assault, if we are able to do so, then the moral duty of northerners was to come to the aid immediately of enslaved human beings in the south, just as [[John Brown (abolitionist)|John Brown]] and [[w:Frederick Douglass|Frederick Douglass]] originally thought.''' But if it was the duty of true abolitionists to take up arms, it would be perverse not to do so just because the political rationale at large was otherwise somewhat morally confused. Thus, '''even if other northerners fought to 'save the Union' rather than to free the slaves, that could have been accepted, as it was by Douglass, as sufficient for the commission of the proper purpose.''' |

||

Revision as of 19:40, 2 August 2015

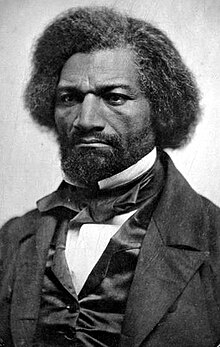

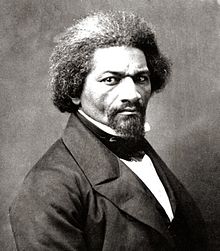

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 20 February 1895) was an African American abolitionist, orator, author, editor, reformer, women's rights advocate, and statesman during the American Civil War. He was born a slave in Maryland, as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey.

Quotes

- They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass. The soul that is within me no man can degrade. I am not the one that is being degraded on account of this treatment, but those who are inflicting it upon me…

- Upon being forced to leave a train car due to his color, as quoted in Up from Slavery (1901), Ch. VI: "Black Race And Red Race, the penalty of telling the truth, of telling the simple truth, in answer to a series of strange questions", by Booker T. Washington.

- Right is of no sex, Truth is of no color, God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren.

- Douglass' chosen motto for his weekly publication The North Star. It appeared on the first issue. As quoted in Maurice S. Lee (2009), The Cambridge Companion to Frederick Douglass. Cambridge University Press, p. 50; Thomson, Conyers & Dawson (2009). The Frederick Douglass Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 149; & Connie A. Miller. Frederick Douglass American Hero: And International Icon of the Nineteenth Century. Xlibris Corporation. p. 144

- I dwell mostly upon the religious aspects, because I believe it is the religious people who are to be relied upon in this Anti-Slavery movement. Do not misunderstand my railing—do not class me with those who despise religion—do not identify me with the infidel. I love the religion of Christianity—which cometh from above—which is a pure, peaceable, gentle, easy to be entreated, full of good fruits, and without hypocrisy. I love that religion which sends its votaries to bind up the wounds of those who have fallen among thieves.

By all the love I bear such a Christianity as this, I hate that of the Priest and the Levite, that with long-faced Phariseeism goes up to Jerusalem to worship and leaves the bruised and wounded to die. I despise that religion which can carry Bibles to the heathen on the other side of the globe and withhold them from the heathen on this side—which can talk about human rights yonder and traffic in human flesh here.... I love that which makes its votaries do to others as they would that others should do to them. I hope to see a revival of it—thank God it is revived. I see revivals of it in the absence of the other sort of revivals. I believe it to be confessed now, that there has not been a sensible man converted after the old sort of way, in the last five years.- As quoted in The Cambridge Companion to Frederick Douglass (2009), by Maurice S. Lee, Cambridge University Press, p. 68-69.

- The man who is right is a majority. We, who have God and conscience on our side, have a majority against the universe.

- I know there is a hope in religion; I know there is faith and I know there is prayer about religion and necessary to it, but God is most glorified when there is peace on earth and good will towards men

- As quoted in The Cambridge Companion to Frederick Douglass (2009), by Maurice S. Lee, Cambridge University Press, p. 70.

- Your wickedness and cruelty committed in this respect on your fellow creatures, are greater than all the stripes you have laid upon my back or theirs. It is an outrage upon the soul, a war upon the immortal spirit, and one for which you must give account at the bar of our common Father and Creator.

- Letter to His Old Master. To my Old Master Thomas Auld.

- I knew that however bad the Republican party was, the Democratic party was much worse. The elements of which the Republican party was composed gave better ground for the ultimate hope of the success of the colored man's cause than those of the Democratic party.

- As quoted in Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1941), chapter 47, p. 579.

- Men have their choice in this world. They can be angels, or they may be demons. In the apocalyptic vision, John describes a war in heaven. You have only to strip that vision of its gorgeous Oriental drapery, divest it of its shining and celestial ornaments, clothe it in the simple and familiar language of common sense, and you will have before you the eternal conflict between right and wrong, good and evil, liberty and slavery, truth and falsehood, the glorious light of love, and the appalling darkness of human selfishness and sin. The human heart is a seat of constant war… Just what takes place in individual human hearts, often takes place between nations, and between individuals of the same nation.

- As quoted in Maurice S. Lee (2009), The Cambridge Companion to Frederick Douglass. Cambridge University Press, p. 50; Thomson, Conyers & Dawson (2009). The Frederick Douglass Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 84

- His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light, his was as the burning sun. Mine was bounded by time. His stretched away to the silent shores of eternity. I could speak for the slave. John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave. John Brown could die for the slave.

- Regarding John Brown, as quoted in A Lecture On John Brown.

- The Republican Party is the ship and all else is the sea around us.

- As quoted in Frederick Douglass American Hero (2008), by Connie A. Miller, Sr., p. 277.

1840s

- I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing, among slaves, as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy, and singing for joy, were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness, as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

- Ch. 2

- Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.

- Ch. 2

- I look upon my departure from Colonel Lloyd's plantation as one of the most interesting events of my life. It is possible, and even quite probable, that but for the mere circumstance of being removed from that plantation to Baltimore, I should have to-day, instead of being here seated by my own table, in the enjoyment of freedom and the happiness of home, writing this Narrative, been confined in the galling chains of slavery. Going to live at Baltimore laid the foundation, and opened the gateway, to all my subsequent prosperity. I have ever regarded it as the first plain manifestation of that kind providence which has ever since attended me, and marked my life with so many favors. I regarded the selection of myself as being somewhat remarkable. There were a number of slave children that might have been sent from the plantation to Baltimore. There were those younger, those older, and those of the same age. I was chosen from among them all, and was the first, last, and only choice.

I may be deemed superstitions, and even egotistical, in regarding this event as a special interposition of divine Providence in my favor. But I should be false to the earliest sentiments of my soul, if I suppressed the opinion. I prefer to be true to myself, even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others, rather than to be false, and incur my own abhorrence. From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom. This good spirit was from God, and to him I offer thanksgiving and praise.- Ch. 5

- Whilst I was saddened by the thought of losing the aid of my kind mistress, I was gladdened by the invaluable instruction which, by the merest accident, I had gained from my master. Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher, I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read. The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering. It gave me the best assurance that that I might rely with the utmost confidence on the results which, he said, would flow from teaching me to read.

- Ch. 6

- The silver trump of freedom had roused my soul to eternal wakefulness. Freedom now appeared, to disappear no more forever. It was heard in every sound, and seen in every thing. It was ever present to torment me with a sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it, I heard nothing without hearing it, and felt nothing without feeling it. It looked from every star, it smiled in every calm, breathed in every wind, and moved in every storm.

- Ch. 7

- I was broken in body, soul and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!

- Ch. 10

- You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.

- Ch. 10

- My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me.

- Ch. 10

- I assert most unhesitatingly, that the religion of the south is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes - a justifier of the most appalling barbarity, — a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds, — and a dark shelter under which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal deeds of slaveholders find the strongest protection.

- Ch. 10

- To make a contented slave it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken the moral and mental vision and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason.

- Ch. 10

- Let us render the tyrant no aid; let us not hold the light by which he can trace the footprints of our flying brother.

- Ch. 11

- I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ; I therefore hate the corrupt, slave-holding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.

- Appendix

- We have men sold to build churches, women sold to support the gospel, and babes sold to purchase Bibles for the poor heathen! all for the glory of God and the good of souls! The slave auctioneer's bell and the church-going bell chime in with each other, and the bitter cries of the heart-broken slave are drowned in the religious shouts of his pious master. Revivals of religion and revivals in the slave-trade go hand in hand.

- Appendix

Letter to William Lloyd Garrison (1846)

- I am now about to take leave of the Emerald Isle, for Glasgow, Scotland. I have been here a little more than four months. Up to this time, I have given no direct expression of the views, feelings and opinions which I have formed, respecting the character and condition of the people in this land. I have refrained thus purposely. I wish to speak advisedly, and in order to do this, I have waited till I trust experience has brought my opinions to an intelligent maturity. I have been thus careful, not because I think what I may say will have much effect in shaping the opinions of the world, but because whatever of influence I may possess, whether little or much, I wish it to go in the right direction, and according to truth. I hardly need say that, in speaking of Ireland, I shall be influenced by prejudices in favor of America. I think my circumstances all forbid that. I have no end to serve, no creed to uphold, no government to defend; and as to nation, I belong to none. I have no protection at home, or resting-place abroad. The land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave, and spurns with contempt the idea of treating me differently. So that I am an outcast from the society of my childhood, and an outlaw in the land of my birth.

- In thinking of America, I sometimes find myself admiring her bright blue sky — her grand old woods — her fertile fields — her beautiful rivers — her mighty lakes, and star-crowned mountains. But my rapture is soon checked, my joy is soon turned to mourning. When I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slaveholding, robbery and wrong, — when I remember that with the waters of her noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean, disregarded and forgotten, and that her most fertile fields drink daily of the warm blood of my outraged sisters, I am filled with unutterable loathing.

- The truth is, the people here know nothing of the republican Negro hate prevalent in our glorious land. They measure and esteem men according to their moral and intellectual worth, and not according to the color of their skin. Whatever may be said of the aristocracies here, there is none based on the color of a man's skin.

Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country (1847)

- I make no pretension to patriotism. So long as my voice can be heard on this or the other side of the Atlantic, I will hold up America to the lightning scorn of moral indignation. In doing this, I shall feel myself discharging the duty of a true patriot; for he is a lover of his country who rebukes and does not excuse its sins. It is righteousness that exalteth a nation while sin is a reproach to any people.

- Speech, "Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country", Syracuse, New York (September 24, 1847)

- Since the light of God’s truth beamed upon my mind, I have become a friend of that religion which teaches us to pray for our enemies — which, instead of shooting balls into their hearts, loves them. I would not hurt a hair of a slaveholder’s head. I will tell you what else I would not do. I would not stand around the slave with my bayonet pointed at his breast, in order to keep him in the power of the slaveholder.

- Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country (October 22, 1847), Delivered at Market Hall, New York City, New York.

- Vainly you talk about voting it down. When you have cast your millions of ballots, you have not reached the evil. It has fastened its root deep into the heart of the nation, and nothing but God’s truth and love can cleanse the land. We must change the moral sentiment.

- Love of God, Love of Man, Love of Country (October 22, 1847), Delivered at Market Hall, New York City, New York.

1850s

- The ground which a colored man occupies in this country is, every inch of it, sternly disputed.

- Speech at the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society annual meeting, New York City (May 1853)

- I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.

- Lecture, The Anti-Slavery Movement (1855)

- In one point of view, we, the abolitionists and colored people, should meet [the Dred Scott] decision, unlooked for and monstrous as it appears, in a cheerful spirit. This very attempt to blot out forever the hopes of an enslaved people may be one necessary link in the chain of events preparatory to the downfall and complete overthrow of the whole slave system.

- We deem it a settled point that the destiny of the colored man is bound up with that of the white people of this country. … We are here, and here we are likely to be. To imagine that we shall ever be eradicated is absurd and ridiculous. We can be remodified, changed, assimilated, but never extinguished. We repeat, therefore, that we are here; and that this is our country; and the question for the philosophers and statesmen of the land ought to be, What principles should dictate the policy of the action toward us? We shall neither die out, nor be driven out; but shall go with this people, either as a testimony against them, or as an evidence in their favor throughout their generations.

- Essay in North Star (November 1858); as quoted in Faces at the Bottom of the Well : The Permanence of Racism (1992) by Derrick Bell, p. 40.

What to the Slave is the Fourth of July? (1852)

- Speech, Corinthian Hall, Rochester, New York (5 July 1852). Full text at Wikisource.

- The 4th of July is the first great fact in your nation's history — the very ring-bolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny. Pride and patriotism, not less than gratitude, prompt you to celebrate and to hold it in perpetual remembrance. I have said that the Declaration of Independence is the ring-bolt to the chain of your nation's destiny; so, indeed, I regard it. The principles contained in that instrument are saving principles. Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.

- This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

- I shall see, this day, and its popular characteristics, from the slave's point of view. Standing, there, identified with the American bondman, making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible, which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to perpetuate slavery — the great sin and shame of America! "I will not equivocate; I will not excuse;" I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgement is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just.

- Douglass here quotes William Lloyd Garrison, who famously declared in the first issue of The Liberator: "I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch — AND I WILL BE HEARD."

- At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could reach the nation's ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed and denounced.

- What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

- You profess to believe "that, of one blood, God made all nations of men to dwell on the face of all the earth," and hath commanded all men, everywhere to love one another; yet you notoriously hate, (and glory in your hatred), all men whose skins are not colored like your own. You declare, before the world, and are understood by the world to declare, that you "hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal; and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; and that, among these are, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness;" and yet, you hold securely, in a bondage which, according to your own Thomas Jefferson, "is worse than ages of that which your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose," a seventh part of the inhabitants of your country.

My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

- I say nothing of father, for he is shrouded in a mystery I have never been able to penetrate. Slavery does away with fathers, as it does away with families. Slavery has no use for either fathers or families, and its laws do not recognize their existence in the social arrangements of the plantation.

- Chapter 3: Parentage.

- I assert most unhesitatingly, that the religion of the South — as I have observed it and proved it — is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes; a justifier of the most appalling barbarity; a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds; and a dark shelter, under which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal abominations fester and flourish. Were I again to be reduced to the condition of A slave, next to that calamity, I should regard the fact of being the slave of a religious slaveholder, the greatest that could befall me.

- Chapter 18: New Relations and Duties.

- The slave is a man, "the image of God," but "a little lower than the angels;" possessing a soul, eternal and indestructible; capable of endless happiness, or immeasurable woe; a creature of hopes and fears, of affections and passions, of joys and sorrows, and he is endowed with those mysterious powers by which man soars above the things of time and sense, and grasps, with undying tenacity, the elevating and sublimely glorious idea of a God. It is such a being that is smitten and blasted. The first work of slavery is to mar and deface those characteristics of its victims which distinguish men from things, and persons from property. Its first aim is to destroy all sense of high moral and religious responsibility. It reduces man to a mere machine. It cuts him off from his Maker, it hides from him the laws of God, and leaves him to grope his way from time to eternity in the dark, under the arbitrary and despotic control of a frail, depraved, and sinful fellow-man. As the serpent-charmer of India is compelled to extract the deadly teeth of his venomous prey before he is able to handle him with impunity, so the slaveholder must strike down the conscience of the slave before he can obtain the entire mastery over his victim.

- The Nature of Slavery. Extract from a Lecture on Slavery, at Rochester, December 1, 1850

- While this nation is guilty of the enslavement of three millions of innocent men and women, it is as idle to think of having a sound and lasting peace, as it is to think there is no God to take cognizance of the affairs of men. There can be no peace to the wicked while slavery continues in the land. It will be condemned; and while it is condemned there will be agitation. Nature must cease to be nature; men must become monsters; humanity must be transformed; Christianity must be exterminated; all ideas of justice and the laws of eternal goodness must be utterly blotted out from the human soul—ere a system so foul and infernal can escape condemnation, or this guilty republic can have a sound, enduring peace.

- The Nature of Slavery. Extract from a Lecture on Slavery, at Rochester, December 1, 1850

- I have shown that slavery is wicked—wicked, in that it violates the great law of liberty, written on every human heart—wicked, in that it violates the first command of the decalogue—wicked, in that it fosters the most disgusting licentiousness—wicked, in that it mars and defaces[345] the image of God by cruel and barbarous inflictions—wicked, in that it contravenes the laws of eternal justice, and tramples in the dust all the humane and heavenly precepts of the New Testament.

- Inhumanity of Slavery. Extract from A Lecture on Slavery, at Rochester. December 8, 1850

- Old as the everlasting hills; immovable as the throne of God; and certain as the purposes of eternal power, against all hinderances, and against all delays, and despite all the mutations of human instrumentalities, it is the faith of my soul, that this anti-slavery cause will triumph.

- The Anti-Slavery Movement. Extracts from a Lecture before Various. Anti-Slavery Bodies, in the Winter of 1855.

West India Emancipation (1857)

- 'An address on West India Emancipation (3 August 1857), according to Frederick Douglass : Selected Speeches and Writings, p. vi ; other sources give 4 August 1857. Other citation source: Frederick Douglass, West India Emancipation Speech, Delivered at Canandaigua, New York (Aug. 4, 1857), in 2 The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass 437 (Philip S. Foner ed., 1950).

- Let me give you a word of the philosophy of reform. The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle. The conflict has been exciting, agitating, all-absorbing, and for the time being, putting all other tumults to silence. It must do this or it does nothing. If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to, and you have found out the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. [...] Men might not get all they work for in this world, but they must certainly work for all they get. If we ever gpt free from the oppressions and wrongs heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal. We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if needs be, by our lives and the lives of others.

1860s

- The American people and the Government at Washington may refuse to recognize it for a time but the inexorable logic of events will force it upon them in the end; that the war now being waged in this land is a war for and against slavery.

- On the American Civil War (1861); as quoted in Afro-American Writing: An Anthology of Prose and Poetry, by Richard A. Long.

- The destiny of the colored American … is the destiny of America.

- Speech at the Emancipation League (12 February 1862), Boston.

- More than twenty years of unswerving devotion to our common cause may give me some humble claim to be trusted at this momentous crisis. I will not argue. To do so implies hesitation and doubt, and you do not hesitate. You do not doubt. The day dawns; the morning star is bright upon the horizon! The iron gate of our prison stands half open. One gallant rush from the North will fling it wide open, while four millions of our brothers and sisters shall march out into liberty. The chance is now given you to end in a day the bondage of centuries, and to rise in one bound from social degradation to the place of common equality with all other varieties of men.

- Men of Color, To Arms! (21 March 1863)

- The relation between the white and colored people of this country is the great, paramount, imperative, and all-commanding question for this age and nation to solve.

- Speech at the Church of the Puritans, New York City (May 1863).

- Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US, let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.

- Speech, "Should the Negro Enlist in the Union Army?", National Hall, Philadelphia (6 July 1863); published in Douglass' Monthly, August 1863

- In regard to the colored people, there is always more that is benevolent, I perceive, than just, manifested towards us. What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us... I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! … And if the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! If you see him on his way to school, let him alone, don't disturb him! If you see him going to the dinner table at a hotel, let him go! If you see him going to the ballot box, let him alone, don't disturb him! If you see him going into a work-shop, just let him alone, — your interference is doing him positive injury.

- I assure you, that this inestimable memento of his Excellency will be retained in my possession while I live — an object of sacred interest — a token not merely of the kind consideration in which I have reason to know that the President was pleased to hold me personally, but as an indication of his humane interest in the welfare of my whole race.

- Letter to Mary Todd Lincoln (17 August 1865).

- A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex.

- Speech (15 November 1867).

- Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day — you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt " God bless you " has been your only reward. The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism. Excepting John Brown — of sacred memory — I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have. Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you. It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony to your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come, that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

- Letter to Harriet Tubman (29 August 1868), as quoted in Harriet, the Moses of Her People (1886) by Sarah Hopkins Bradford, p. 135.

The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery? (1860)

- "The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?" (26 March 1860), Glasgow, United Kingdom.

- I, on the other hand, deny that the Constitution guarantees the right to hold property in man, and believe that the way to abolish slavery in America is to vote such men into power as well use their powers for the abolition of slavery. This is the issue plainly stated, and you shall judge between us.

- What, then, is the Constitution? I will tell you. It is not even like the British Constitution, which is made up of enactments of Parliament, decisions of Courts, and the established usages of the Government. The American Constitution is a written instrument full and complete in itself. No Court in America, no Congress, no President, can add a single word thereto, or take a single word threreto. It is a great national enactment done by the people, and can only be altered, amended, or added to by the people. I am careful to make this statement here; in America it would not be necessary. It would not be necessary here if my assailant had shown the same desire to be set before you the simple truth, which he manifested to make out a good case for himself and friends.

- Again, it should be borne in mind that the mere text, and only the text, and not any commentaries or creeds written by those who wished to give the text a meaning apart from its plain reading, was adopted as the Constitution of the United States. It should also be borne in mind that the intentions of those who framed the Constitution, be they good or bad, for slavery or against slavery, are so respected so far, and so far only, as we find those intentions plainly stated in the Constitution. It would be the wildest of absurdities, and lead to endless confusion and mischiefs, if, instead of looking to the written paper itself, for its meaning, it were attempted to make us search it out, in the secret motives, and dishonest intentions, of some of the men who took part in writing it. It was what they said that was adopted by the people, not what they were ashamed or afraid to say, and really omitted to say.

- Bear in mind, also, and the fact is an important one, that the framers of the Constitution sat with doors closed, and that this was done purposely, that nothing but the result of their labours should be seen, and that that result should be judged of by the people free from any of the bias shown in the debates. It should also be borne in mind, and the fact is still more important, that the debates in the convention that framed the Constitution, and by means of which a pro-slavery interpretation is now attempted to be forced upon that instrument, were not published till more than a quarter of a century after the presentation and the adoption of the Constitution.

- The Constitution itself. Its language is 'we the people'. Not we the white people, not even we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low, but we the people. Not we the horses, sheep, and swine, and wheel-barrows, but we the people, we the human inhabitants.

- If Negroes are people, they are included in the benefits for which the Constitution of America was ordained and established. But how dare any man who pretends to be a friend to the Negro thus gratuitously concede away what the Negro has a right to claim under the Constitution? Why should such friends invent new arguments to increase the hopelessness of his bondage? This, I undertake to say, as the conclusion of the whole matter, that the constitutionality of slavery can be made out only by disregarding the plain and common-sense reading of the Constitution itself; by discrediting and casting away as worthless the most beneficent rules of legal interpretation; by ruling the Negro outside of these beneficent rules; by claiming that the Constitution does not mean what it says, and that it says what it does not mean; by disregarding the written Constitution, and interpreting it in the light of a secret understanding. It is in this mean, contemptible, and underhand method that the American Constitution is pressed into the service of slavery. They go everywhere else for proof that the Constitution declares that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; it secures to every man the right of trial by jury, the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus — the great writ that put an end to slavery and slave-hunting in England — and it secures to every State a republican form of government. Anyone of these provisions in the hands of abolition statesmen, and backed up by a right moral sentiment, would put an end to slavery in America.

- The Constitution forbids the passing of a bill of attainder: that is, a law entailing upon the child the disabilities and hardships imposed upon the parent. Every slave law in America might be repealed on this very ground. The slave is made a slave because his mother is a slave. But to all this it is said that the practice of the American people is against my view. I admit it. They have given the Constitution a slaveholding interpretation. I admit it. Thy have committed innumerable wrongs against the Negro in the name of the Constitution. Yes, I admit it all; and I go with him who goes farthest in denouncing these wrongs. But it does not follow that the Constitution is in favor of these wrongs because the slaveholders have given it that interpretation. To be consistent in his logic, the City Hall speaker must follow the example of some of his brothers in America — he must not only fling away the Constitution, but the Bible. The Bible must follow the Constitution, for that, too, has been interpreted for slavery by American divines. Nay, more, he must not stop with the Constitution of America, but make war with the British Constitution, for, if I mistake not, the gentleman is opposed to the union of Church and State. In America he called himself a Republican. Yet he does not go for breaking down the British Constitution, although you have a Queen on the throne, and bishops in the House of Lords.

- My argument against the dissolution of the American Union is this. It would place the slave system more exclusively under the control of the slave-holding states, and withdraw it from the power in the northern states which is opposed to slavery. Slavery is essentially barbarous in its character. It, above all things else, dreads the presence of an advanced civilization. It flourishes best where it meets no reproving frowns, and hears no condemning voices. While in the Union it will meet with both. Its hope of life, in the last resort, is to get out of the Union. I am, therefore, for drawing the bond of the Union more completely under the power of the free states. What they most dread, that I most desire. I have much confidence in the instincts of the slaveholders. They see that the Constitution will afford slavery no protection when it shall cease to be administered by slaveholders. They see, moreover, that if there is once a will in the people of America to abolish slavery, this is no word, no syllable in the Constitution to forbid that result. They see that the Constitution has not saved slavery in Rhode Island, in Connecticut, in New York, or Pennsylvania; that the Free States have only added three to their original number. There were twelve Slave States at the beginning of the Government: there are fifteen now.

- The dissolution of the Union would not give the North a single advantage over slavery, but would take from it many. Within the Union we have a firm basis of opposition to slavery. It is opposed to all the great objects of the Constitution. The dissolution of the Union is not only an unwise but a cowardly measure; fifteen millions running away from three hundred and fifty thousand slaveholders. Mr. Garrison and his friends tell us that while in the Union we are responsible for slavery. He and they sing out 'No Union with slaveholders', and refuse to vote. I admit our responsibility for slavery while in the Union but I deny that going out of the Union would free us from that responsibility. There now clearly is no freedom from responsibility for slavery to any American citizen short to the abolition of slavery. The American people have gone quite too far in this slaveholding business now to sum up their whole business of slavery by singing out the cant phrase, 'No union with slaveholders'. To desert the family hearth may place the recreant husband out of the presence of his starving children, but this does not free him from responsibility. If a man were on board of a pirate ship, and in company with others had robbed and plundered, his whole duty would not be preformed simply by taking the longboat and singing out, 'No union with pirates'. His duty would be to restore the stolen property.

- The American people in the Northern States have helped to enslave the black people. Their duty will not have been done till they give them back their plundered rights. Reference was made at the City Hall to my having once held other opinions, and very different opinions to those I have now expressed. An old speech of mine delivered fourteen years ago was read to show — I know not what. Perhaps it was to show that I am not infallible. If so, I have to say in defense, that I never pretended to be.

- Although I cannot accuse myself of being remarkably unstable, I do not pretend that I have never altered my opinion both in respect to men and things. Indeed, I have been very much modified both in feeling and opinion within the last fourteen years. When I escaped from slavery, and was introduced to the Garrisonians, I adopted very many of their opinions, and defended them just as long as I deemed them true. I was young, had read but little, and naturally took some things on trust. Subsequent experience and reading have led me to examine for myself. This had brought me to other conclusions. When I was a child, I thought and spoke as a child. But the question is not as to what were my opinions fourteen years ago, but what they are now. If I am right now, it really does not matter what I was fourteen years ago. My position now is one of reform, not of revolution. I would act for the abolition of slavery through the Government — not over its ruins. If slaveholders have ruled the American Government for the last fifty years, let the anti-slavery men rule the nation for the next fifty years. If the South has made the Constitution bend to the purposes of slavery, let the North now make that instrument bend to the cause of freedom and justice. If 350,000 slaveholders have, by devoting their energies to that single end, been able to make slavery the vital and animating spirit of the American Confederacy for the last 72 years, now let the freemen of the North, who have the power in their own hands, and who can make the American Government just what they think fit, resolve to blot out for ever the foul and haggard crime, which is the blight and mildew, the curse and the disgrace of the whole United States.

Our Composite Nationality (1869)

- "Our Composite Nationality" (7 December 1869), Boston, Massachusetts.

- As nations are among the largest and the most complete divisions into which society is formed, the grandest aggregations of organized human power; as they raise to observation and distinction the world’s greatest men, and call into requisition the highest order of talent and ability for their guidance, preservation and success, they are ever among the most attractive, instructive and useful subjects of thought, to those just entering upon the duties and activities of life.

- The simple organization of a people into a national body, composite or otherwise, is of itself an impressive fact. As an original proceeding, it marks the point of departure of a people, from the darkness and chaos of unbridled barbarism, to the wholesome restraints of public law and society. It implies a willing surrender and subjection of individual aims and ends, often narrow and selfish, to the broader and better ones that arise out of society as a whole. It is both a sign and a result of civilization. A knowledge of the character, resources and proceedings of other nations, affords us the means of comparison and criticism, without which progress would be feeble, tardy, and perhaps, impossible. It is by comparing one nation with another, and one learning from another, each competing with all, and all competing with each, that hurtful errors are exposed, great social truths discovered, and the wheels of civilization whirled onward.

- I am especially to speak to you of the character and mission of the United States, with special reference to the question whether we are the better or the worse for being composed of different races of men. I propose to consider first, what we are, second, what we are likely to be, and, thirdly, what we ought to be. Without undue vanity or unjust depreciation of others, we may claim to be, in many respects, the most fortunate of nations. We stand in relations to all others, as youth to age. Other nations have had their day of greatness and glory; we are yet to have our day, and that day is coming. The dawn is already upon us. It is bright and full of promise. Other nations have reached their culminating point. We are at the beginning of our ascent. They have apparently exhausted the conditions essential to their further growth and extension, while we are abundant in all the material essential to further national growth and greatness. The resources of European statesmanship are now sorely taxed to maintain their nationalities at their ancient height of greatness and power. American statesmanship, worthy of the name, is now taxing its energies to frame measures to meet the demands of constantly increasing expansion of power, responsibility and duty. Without fault or merit on either side, theirs or ours, the balance is largely in our favor. Like the grand old forests, renewed and enriched from decaying trunks once full of life and beauty, but now moss-covered, oozy and crumbling, we are destined to grow and flourish while they decline and fade. This is one view of American position and destiny. It is proper to notice that it is not the only view. Different opinions and conflicting judgments meet us here, as elsewhere.

- It is thought by many, and said by some, that this republic has already seen its best days; that the historian may now write the story of its decline and fall. Two classes of men are just now especially afflicted with such forebodings. The first are those who are croakers by nature. The men who have a taste for funerals, and especially national funerals. They never see the bright side of anything, and probably never will. Like the raven in the lines of Edgar A. Poe, they have learned two words, and those are, 'never more'. They usually begin by telling us what we never shall see. Their little speeches are about as follows: You will never see such statesmen in the councils of the Nations as Clay, Calhoun and Webster. You will never see the south morally reconstructed and our once happy people again united. You will never see this Government harmonious and successful while in the hands of different races. You will never make the negro work without a master, or make him an intelligent voter, or a good and useful citizen. This last never is generally the parent of all the other little 'nevers' that follow.

- During the late contest for the Union, the air was full of 'nevers', every one of which was contradicted and put to shame by the result, and I doubt not that most of those we now hear in our troubled air will meet the same fate. It is probably well for us that some of our gloomy prophets are limited in their powers to prediction. Could they commend the destructive bolt, as readily as they commend the destructive word, it is hard to say what might happen to the country. They might fulfill their own gloomy prophecies. Of course it is easy to see why certain other classes of men speak hopelessly concerning us. A Government founded upon justice, and recognizing the equal rights of all men; claiming no higher authority for its existence, or sanction for its laws, than nature, reason and the regularly ascertained will of the people; steadily refusing to put its sword and purse in the service of any religious creed or family, is a standing offense to most of the governments of the world, and to some narrow and bigoted people among ourselves.

- To those who doubt and deny the preponderance of good over evil in human nature; who think the few are made to rule, and the many to serve; who put rank above brotherhood, and race above humanity; who attach more importance to ancient forms than to the living realities of the present; who worship power in whatever hands it may be lodged and by whatever means it may have been obtained; our government is a mountain of sin, and, what is worse, it seems confirmed in its transgressions. One of the latest and most potent European prophets, one who felt himself called upon for a special deliverance concerning us and our destiny as a nation, was the late Thomas Carlyle. He described us as rushing to ruin, and when we may expect to reach the terrible end, our gloomy prophet, enveloped in the fogs of London, has not been pleased to tell us. Warning and advice from any quarter are not to be despised, and especially not from one so eminent as Mr. Carlyle; and yet Americans will find it hard to heed even men like him, while the animus is so apparent, bitter and perverse.

- A man to whom despotism is the savior and liberty the destroyer of society, who, during the last twenty years, in every contest between liberty and oppression, uniformally and promptly took sides with the oppressor; who regarded every extension of the right of suffrage, even to white men in his own country, as shooting Niagara; who gloated over deeds of cruelty, and talked of applying to the backs of men the beneficent whip, to the great delight of many of the slaveholders of America in particular, could have but little sympathy with our emancipated and progressive Republic, or with the triumph of liberty any where. But the American people can easily stand the utterances of such a man. They however have a right to be impatient and indignant at those among ourselves who turn the most hopeful portents into omens of disaster, and make themselves the ministers of despair, when they should be those of hope, and help cheer on the country in the new grand career of justice upon which it has now so nobly and bravely entered.

- Of errors and defects we certainly have not less than our full share, enough to keep the reformer awake, the statesman busy, and the country in a pretty lively state of agitation for some time to come. Perfection is an object to be aimed at by all, but it is not an attribute of any form of government. Mutability is the law for all. Something different, something better, or something worse may come, but so far as respects our present system and form of government, and the altitude we occupy, we need not shrink from comparison with any nation of our times. We are to day the best fed, the best clothed, the best sheltered and the best instructed people in the world.

- There was a time when even brave men might look fearfully upon the destiny of the Republic; when our country was involved in a tangled network of contradictions; when vast and irreconcilable social forces fiercely disputed for ascendency and control; when a heavy curse rested upon our very soil, defying alike the wisdom and the virtue of the people to remove it; when our professions were loudly mocked by our practice, and our name was a reproach and a byword to a mocking; when our good ship of state, freighted with the best hopes of the oppressed of all nations, was furiously hurled against the hard and flinty rocks of derision, and every cord, bolt, beam and bend in her body quivered beneath the shock, there was some apology for doubt and despair. But that day has happily passed away. The storm has been weathered, and the portents are nearly all in our favor.

- There are clouds, wind, smoke and dust and noise, over head and around, and there always will be; but no genuine thunder, with destructive bolt, menaces from any quarter of the sky. The real trouble with us was never our system or form of government, or the principles underlying it, but the peculiar composition of our people; the relations existing between them and the compromising spirit which controlled the ruling power of the country.

- We have for a long time hesitated to adopt and carry out the only principle which can solve that difficulty and give peace, strength and security to the republic, and that is the principle of absolute equality. We are a country of all extremes, ends and opposites. The most conspicuous example of composite nationality in the world. Our people defy all the ethnological and logical classifications. In races we range all the way from black to white, with intermediate shades which, as in the apocalyptic vision, no man can name or number.

- In regard to creeds and faiths, the condition is no better, and no worse. Differences both as to race and to religion are evidently more likely to increase than to diminish. We stand between the populous shores of two great oceans. Our land is capable of supporting one-fifth of all the globe. Here, labor is abundant and better renumerated than any where else. All moral, social and geographical causes conspire to bring to us the peoples of all other over populated countries.

- Europe and Africa are already here, and the Indian was here before either. He stands today between the two extremes of black and white, too proud to claim fraternity with either, and yet too weak to withstand the power of either. Heretofore, the policy of our government has been governed by race pride, rather than by wisdom. Until recently, neither the Indian nor the negro has been treated as a part of the body politic. No attempt has been made to inspire either with a sentiment of patriotism, but the hearts of both races have been diligently sown with the dangerous seeds of discontent and hatred.

- The policy of keeping the Indians to themselves, has kept the tomahawk and scalping knife busy upon our borders, and has cost us largely in blood and treasure. Our treatment of the negro has lacked humanity and filled the country with agitation and ill-feeling, and brought the nation to the verge of ruin. Before the relations of those two races are satisfactorily settled, and in despite of all opposition, a new race is making its appearance within our borders, and claiming attention. It is estimated that not less than one hundred thousand Chinamen are now within the limits of the United States. Several years ago every vessel, large or small, of steam or of sail, bound to our Pacific coast and hailing from the Flowery kingdom, added to the number and strength of this new element of our population.

- Men differ widely as to the magnitude of this potential Chinese immigration. The fact that by the late treaty with China we bind ourselves to receive immigrants from that country only as the subjects of the Emperor, and by the construction at least are bound not to naturalize them, and the further fact that Chinamen themselves have a superstitious devotion to their country and an aversion to permanent location in any other, contracting even to have their bones carried back, should they die abroad, and from the fact that many have returned to China, and the still more stubborn fact that resistance to their coming has increased rather than diminished, it is inferred that we shall never have a large Chinese population in America. This, however, is not my opinion. It may be admitted that these reasons, and others, may check and moderate the tide of immigration; but it is absurd to think that they will do more than this. Counting their number now by the thousands, the time is not remote when they will count them by the millions. The emperor hold upon the Chinamen may be strong, but the Chinaman's hold upon himself is stronger.

- Treaties against naturalization, like all other treaties, are limited by circumstances. As to the superstitious attachment of the Chinese to China, that, like all other superstitions, will dissolve in the light and heat of truth and experience. The Chinaman may be a bigot, but it does not follow that he will continue to be one tomorrow. He is a man, and will be very likely to act like a man. He will not be long in finding out that a country that is good enough to live in is good enough to die in, and that a soil that was good enough to hold his body while alive, will be good enough to hold his bones when he is dead. Those who doubt a large immigration should remember that the past furnishes no criterion as a basis of calculation. We live under new and improved conditions of migration, and these conditions are constantly improving.

- America is no longer an obscure and inaccessible country. Our ships are in every sea, our commerce is in every port, our language is heard all around the globe, steam and lightning have revolutionized the whole domain of human thought, changed all geographical relations, make a day of the present seem equal to a thousand years of the past, and the continent that Columbus only conjectured four centuries ago is now the center of the world.

- Southern gentlemen who led in the late rebellion have not parted with their convictions at this point, any more than at any other. They want to be independent of the negro. They believed in slavery and they believe in it still. They believed in an aristocratic class, and they believe in it still, and though they have lost slavery, one element essential to such a class, they still have two important conditions to the reconstruction of that class. They have intelligence, and they have land. Of these, the land is the more important. They cling to it with all the tenacity of a cherished superstition. They will neither sell to the negro, nor let the carpet-bagger have it in peace, but are determined to hold it for themselves and their children forever. They have not yet learned that when a principle is gone, the incident must go also; that what was wise and proper under slavery is foolish and mischievous in a state of general liberty; that the old bottles are worthless when the new wine has come; but they have found that land is a doubtful benefit, where there're no hands to till it. Hence these gentlemen have turned their attention to the Celestial Empire. They would rather have laborers who would work for nothing; but as they cannot get the negro on these terms, they want Chinamen, who, they hope, will work for next to nothing.

- Companies and associations may yet be formed to promote this Mongolian invasion. The loss of the negro is to gain them the Chinese, and if the thing works well, abolition, in their opinion, will have proved itself to be another blessing in disguise. To the statesman it will mean Southern independence. To the pulpit, it will be the hand of Providence, and bring about the time of the universal dominion of the Christian religion. To all but the Chinaman and the negro it will mean wealth, ease and luxury. But alas, for all the selfish invention and dreams of men! The Chinaman will not long be willing to wear the cast off shoes of the negro, and, if he refuses, there will be trouble again. The negro worked and took his pay in religion and the lash. The Chinaman is a different article and will want the cash. He may, like the negro, accept Christianity, but, unlike the negro, he will not care to pay for it in labor. He had the Golden Rule in substance five hundred years before the coming of Christ, and has notions of justice that are not to be confused by any.

- Nevertheless, the experiment will be tried. So far as getting the Chinese into our country is concerned, it will yet be a success. This elephant will be drawn by our southern brethren, though they will hardly know in the end what to do with him. Appreciation of the value of Chinamen as laborers will, I apprehend, become general in this country. The north was never indifferent to the southern influence and example, and it will not be so in this instance. The Chinese in themselves have first rate recommendations. They are industrious, docile, cleanly, frugal. They are dexterous of hand, patient in toil, marvelously gifted in the power of imitation, and have but few wants. Those who have carefully observed their habits in California say that they subsist upon what would be almost starvation to others. The conclusion of the whole will be that they will want to come to us, and, as we become more liberal, we shall want them to come, and what we want done will naturally be done. They will no longer halt upon the shores of California. They will burrow no longer in her exhausted and deserted gold mines, where they have gathered wealth from barrenness, taking what others left. They will turn their backs not only upon the Celestial Empire but upon the golden shores of the Pacific, and the wide waste of waters whose majestic waves spoke to them of home and country. They will withdraw their eyes from the glowing West and fix them upon the rising sun. They will cross the mountains, cross the plains, descend our rivers, penetrate to the heart of the country and fix their home with us forever.

- Assuming then that immigration already has a foothold and will combine for many years to come, we have a new element in our national composition which is likely to exercise a large influence upon the thought and the action of the whole nation.

- The old question as to what shall be done with the negro will have to give place to the greater question “What shall be done with the Mongolian,” and perhaps we shall see raised one still greater, namely, “What will the Mongolian do with both the negro and the white?” Already has the matter taken shape in California and on the Pacific coast generally. Already has California assumed a bitterly unfriendly attitude toward the Chinaman. Already has she driven them from her altars of justice. Already has she stamped them as outcasts and handed them over to popular contempts and vulgar jest. Already are they the constant victims of cruel harshness and brutal violence. Already have our Celtic brothers, never slow to execute the behests of popular prejudice against the weak and defenseless, recognized in the heads of these people, fit targets for their shilalahs. Already, too, are their associations formed in avowed hostility to the Chinese. In all this there is, of course, nothing strange. Repugnance to the presence and influence of foreigners is an ancient feeling among men. It is peculiar to no particular race or nation. It is met with, not only in the conduct of one nation towards another, but in the conduct of the inhabitants of the different parts of the same country, some times of the same city, and even of the same village. 'Lands intersected by a narrow frith abhor each other. Mountains interposed, make enemies of nations'. To the Greek, every man not speaking Greek is a barbarian. To the Jew, everyone not circumcised is a gentile. To the Mohametan, every one not believing in the Prophet is a kaffer.

- I need not repeat here the multitude of reproachful epithets expressive of the same sentiment among ourselves. All who are not to the manor born have been made to feel the lash and sting of these reproachful names. For this feeling there are many apologies, for there was never yet an error, however flagrant and hurtful, for which some plausible defense could not be framed. Chattel slavery, king craft, priest craft, pious frauds, intolerance, persecution, suicide, assassination, repudiation, and a thousand other errors and crimes have all had their defenses and apologies.Prejudice of race and color has been equally upheld. The two best arguments in the defence are, first, the worthlessness of the class against which it is directed; and, second, that the feeling itself is entirely natural. The two best arguments in the defense are, first, the worthlessness of the class against which it is directed; and, second, that the feeling itself is entirely natural. The way to overcome the first argument is to work for the elevation of those deemed worthless, and thus make them worthy of regard, and they will soon become worthy and not worthless. As to the natural argument, it may be said that nature has many sides. Many things are in a certain sense natural, which are neither wise nor best. It is natural to walk, but shall men therefore refuse to ride? It is natural to ride on horseback, shall men therefore refuse stream and rail? Civilization is itself a constant war upon some forces in nature, shall we therefore abandon civilization and go back to savage life? Nature has two voices, the one high, the other low; one is in sweet accord with reason and justice, and the other apparently at war with both. The more men know of the essential nature of things, and of the true relation of mankind, the freer they are from prejudice of every kind. The child is afraid of the giant form of his own shadow. This is natural, but he will part with his fears when he is older and wiser. So ignorance is full of prejudice, but it will disappear with enlightenment. But I pass on.

- I have said that the Chinese will come, and have given some reasons why we may expect them in very large numbers in no very distant future. Do you ask if I would favor such immigrations? I answer, I would. 'Would you admit them as witnesses in our courts of law?' I would. Would you have them naturalized, and have them invested with all the rights of American citizenship? I would. Would you allow them to vote? I would. Would you allow them to hold office? I would.

- But are there not reasons against all this? Is there not such a law or principle as that of self-preservation? Does not every race owe something to itself? Should it not attend to the dictates of common sense? Should not a superior race protect itself from contact with inferior ones? Are not the white people the owners of this continent? Have they not the right to say what kind of people shall be allowed to come here and settle? Is there not such a thing as being more generous than wise? In the effort to promote civilization may we not corrupt and destroy what we have? Is it best to take on board more passengers than the ship will carry? To all this and more I have one among many answers, altogether satisfactory to me, though I cannot promise it will be entirely so to you. I submit that this question of Chinese immigration should be settled upon higher principles than those of a cold and selfish expediency. There are such things in the world as human rights. They rest upon no conventional foundation, but are eternal, universal and indestructible. Among these is the right of locomotion; the right of migration; the right which belongs to no particular race, but belongs alike to all and to all alike. It is the right you assert by staying here, and your fathers asserted by coming here. It is this great right that I assert for the Chinese and the Japanese, and for all other varieties of men equally with yourselves, now and forever. I know of no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity, and when there is a supposed conflict between human and national rights, it is safe to go the side of humanity. I have great respect for the blue-eyed and light-haired races of America. They are a mighty people. In any struggle for the good things of this world, they need have no fear, they have no need to doubt that they will get their full share. But I reject the arrogant and scornful theory by which they would limit migratory rights, or any other essential human rights, to themselves, and which would make them the owners of this great continent to the exclusion of all other races of men. I want a home here not only for the negro, the mulatto and the Latin races, but I want the Asiatic to find a home here in the United States, and feel at home here, both for his sake and for ours.

- Right wrongs no man. If respect is had to majorities, the fact that only one-fifth of the population of the globe is white and the other four-fifths are colored, ought to have some weight and influence in disposing of this and similar questions. It would be a sad reflection upon the laws of nature and upon the idea of justice, to say nothing of a common Creator, if four-fifths of mankind were deprived of the rights of migration to make room for the one-fifth. If the white race may exclude all other races from this continent, it may rightfully do the same in respect to all other lands, islands, capes and continents, and thus have all the world to itself, and thus what would seem to belong to the whole would become the property of only a part. So much for what is right, now let us see what is wise.

- And here I hold that a liberal and brotherly welcome to all who are likely to come to the United States is the only wise policy which this nation can adopt. It has been thoughtfully observed that every nation, owing to its peculiar character and composition, has a definite mission in the world. What that mission is, and what policy is best adapted to assist in its fulfillment, is the business of its people and its statesmen to know, and knowing, to make a noble use of this knowledge. I need not stop here to name or describe the missions of other or more ancient nationalities. Our seems plain and unmistakable. Our geographical position, our relation to the outside world, our fundamental principles of government, world-embracing in their scope and character, our vast resources, requiring all manner of labor to develop them, and our already existing composite population, all conspire to one grand end, and that is, to make us the perfect national illustration of the unity and dignity of the human family that the world has ever seen. In whatever else other nations may have been great and grand, our greatness and grandeur will be found in the faithful application of the principle of perfect civil equality to the people of all races and of all creeds. We are not only bound to this position by our organic structure and by our revolutionary antecedents, but by the genius of our people. Gathered here from all quarters of the globe, by a common aspiration for national liberty as against caste, divine right govern and privileged classes, it would be unwise to be found fighting against ourselves and among ourselves, it would be unadvised to attempt to set up any one race above another, or one religion above another, or prescribe any on account of race, color or creed.

- The apprehension that we shall be swamped or swallowed up by Mongolian civilization; that the Caucasian race may not be able to hold their own against that vast incoming population, does not seem entitled to much respect. Though they come as the waves come, we shall be all the stronger if we receive them as friends and give them a reason for loving our country and our institutions. They will find here a deeply rooted, indigenous, growing civilization, augmented by an ever-increasing stream of immigration from Europe, and possession is nine points of the law in this case, as well as in others. They will come as strangers. We are at home. They will come to us, not we to them. They will come in their weakness, we shall meet them in our strength. They will come as individuals, we will meet them in multitudes, and with all the advantages of organization. Chinese children are in American schools in San Francisco. None of our children are in Chinese schools, and probably never will be, though in some things they might well teach us valuable lessons. Contact with these yellow children of the Celestial Empire would convince us that the points of human difference, great as they, upon first sight, seem, are as nothing compared with the points of human agreement. Such contact would remove mountains of prejudice.

- It is said that it is not good for man to be alone. This is true, not only in the sense in which our women’s rights’ friends so zealously and wisely teach, but it is true as to nations. The voice of civilization speaks an unmistakable language against the isolation of families, nations and races, and pleads for composite nationality as essential to her triumphs. Those races of men who have maintained the most distinct and separate existence for the longest periods of time; which have had the least intercourse with other races of men are standing confirmation of the folly of isolation. The very soil of the national mind becomes in such cases barren, and can only be resuscitated by assistance from without.