Paul Cézanne

Appearance

(Redirected from Cezanne)

Paul Cézanne (January 19, 1839 – October 22, 1906) was a French Post-Impressionist painter whose work laid the foundations of the transition from the 19th century conception of artistic endeavour to a new and radically different world of art in the 20th century. Cézanne can be said to form the bridge between late 19th century Impressionism and the early 20th century's new line of artistic enquiry, Cubism.

Quotes of Paul Cézanne

[edit]- sorted chronologically, by date of the quotes of Paul Cézanne

1860s - 1870s

[edit]- I've ripped it to pieces; your portrait, you know. I tried to work on it this morning, but it went from bad to worse, so I destroyed it..

- Quote of Cezanne, from his letter to Emile Zola, ca 1861; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 23

- Don't you think your Corot [to Guilemet the painter] is a little short on temperament? I'm painting a portrait of Vallabreque; the highlight on the nose is pure vermilion [remark of Cezanne ca. 1860]

- Quote in: Cézanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 28

- He (the painter Manet) hits of the tone.. ..but his work lacks unity and temperament too. (ca. 1863)

- Quote in: Cézanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 27

- At Aix (Aix en Provence) I am not free; whenever I want to return to Paris, I always have to put up a fight, and, although your (his father) opposition may not be absolute, I am always deeply affected by the resistance that I encounter from you. I sincerely want my liberty unfettered.. ..it would give me great pleasure to work in the Midi, some aspects of which offer many resources to the painter; there I would be able to attack some of the problems that I wish to solve.

- Quote in Cezanne's letter to his father in Aix; ca. 1871-73; as quoted in Cézanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, pp. 33-34

- Listen, monsieur Vollard, I worked a lot out of doors at L'Estaque. Except for that there was no other event of importance in my life during the years 1870-71. I divided my time between the field and the studio... Zola closed his letter by urging me to come back to Paris too [in 1872 Cézanne went back to Paris].. ..but all the same, something told me to go back to Paris. It was too long since I had seen the Louvre. But understand, Monsieur Vollard, I was working at that time on a landscape which was not going well. So I stayed at Aix a little while longer to study on my canvas.

- Quote in: Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 32-33

- If I dared, I should say that your [ Camille Pissarro ] letter is imprinted with sadness. The picture business isn't going well; I fear that your morale may be colored a little grey, but I'm sure that it's only a passing phase.. .I imagine that you would be delighted with the country where I am now.. ..in L'Estaque, by the sea. I haven't been in Aix for a month. I've started two little motifs of the sea, for Monsieur [Victor] Chocquet [one of them became his later painting 'The Sea at L'Estaque', who had talked to me about it. It's like a playing card. Red roofs against the blue sea. If the weather turns favorable perhaps I'll be able to finish them off.

- Quote from Cezanne's letter to Camille Pissarro, from L'Estaque 2 July 1876, taken from Alex Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, 2013; as quoted in the 'Daily Beast' online, 13 Oct. 2013

- But there are motifs that would need three or four months' work, which could be done, as the vegetation doesn't change here. There are the olive trees and the pines that always keep their leaves. The sun is so fierce that objects seem to be silhouetted, not only in black or white, but in blue, red, brown, violet. I may be wrong, but this seems to be the very opposite of 'modeling'. How happy the gentle landscapists of Auvers would be here, and that [con, or 'bastard'?] Guillemet.

- Quote from Cezanne's letter to Camille Pissarro, from L'Estaque 2 July 1876, taken from Alex Danchev, The Letters of Paul Cézanne, 2013; as quoted in the 'Daily Beast' online, 13 Oct. 2013

- 'The very opposite of 'modeling' meant roughly that Cézanne and Pissarro in their common painting-years in open air would lay down one plane or patch of color next to another in the painting, without any 'modeling' or shading between them - so that it looked as if each component part of the painting could be picked up from the canvas a little like a 'playing card from the table', as Cezanne explains here.

- I had the company of monsieur Gibert. Such people see clearly, but they have the teacher's eye. As the train was taking us past Alexis' place a staggering subject for a picture came into view towards the east: St-Victoire [later Cezanne made series of paintings of Mont St. Victoire and the crags above Beaurecueil]. I said, 'What a splendid subject'; he replied, 'The lines are too symmetrical'. Referring to 'L'Assommoir' [a novel of Emile Zola ] about which, incidentally, he was the first person to speak to me, he said some very sound things, and praised it, but always from the point of view of technique.

- Quote in Cézanne's letter to his friend Emile Zola, Aix-en-Provence, 14 April 1878; as quoted in Letters of the great artists – from Blake to Pollock"', Richard Friedenthal, Thames and Hudson, London, 1963, pp. 178-179

1880s - 1890s

[edit]- I saw Monet and Renoir at about the end of December; they had been on holiday in Genoa, in Italy.

- Quote in Cezanne's letter to Emile Zola, 23rd February 1884; as quoted in Renoir – his life and work, Francois Fosca, Book Club Associates /Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1975, p. 175

- You positively paint like a madman.

- As quoted in: 'Mercure de France', 16 December 1908, p. 607

- remark to Vincent van Gogh, ca. 1886 in Paris. Van Gogh showed Cezanne some of his recent paintings, he recently made in Paris

- I was very pleased with myself when I discovered that sunlight could not be reproduced; it had to be represented by something else.. ..by colour.

- Quote from Renoir – his life and work, Francois Fosca; Book Club Associates /Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1975, p. 79

- You wretch! [Cezanne is portraying the art dealer Vollard who changed his pose during the painter session] You've spoiled the pose. Do I have to tell you again you must sit like an apple? Does an apple move?

- Quote from a conversation in Cézanne's studio in Paris, ca. 1896-98; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 74

- ..that distinguished aesthete [ Gustave Moreau,] famous artist and art teacher in Paris, then] who paints nothing than rubbish, it is because his dreams are suggested not by the inspiration of Nature, but by what he has seen in the museums.. .I should like to have that good man under my wing, to point out to him the doctrine of a development of art by contact with Nature. It's so sane, so comforting, the only just conception of art.

- Quote in a conversation with Vollard, in the studio of Cézanne, in Aix, 1896; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 66

- ..The Night-watch (large and famous painting of Dutch 17th century painter Rembrandt.. ..the grandiose - I don't say it in bad part - grows tiresome after a while. There are mountains like that; when you stand before them you shout Nom de Dieu, but for every day a simple little hill does well enough. Listen Monsieur Vollard, if the 'Raft of the Medusa' of Théodore Géricault hung in my bedroom, it would make me sick.

- Quote from a conversation with Vollard, in the studio of Cézanne, in Aix, 1896; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 67

- Everybody's going crazy over the Impressionists; what art needs is a Poussin made over according to nature. There you have it in a nutshell.

- Quote from a conversation with Vollard, in the studio of Cézanne, in Aix, 1896; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 67

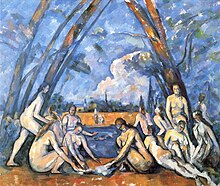

- Wouldn't it be wonderful to paint a nude here? [along the river near Aix ] There are innumerable motifs here on the banks of the river; the same spot viewed from a different angle offers a subject of the utmost interest. It is so varied that I think I could keep busy for months without changing my place, simply turning now tot the right and now to the left.

- Quote in a conversation with Vollard, along the river near Aix, 1896; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 74

- Painting certainly means more to me than everything else in the world. I think my mind becomes clearer when I am in the presence of nature. Unfortunately, the realization of my sensations is always a very painful process with me. I can't seem to express the intensity which beats in upon my senses. I haven't at my command the magnificent richness of color which enlivens Nature.. .Look at that cloud; I should like to be able to paint that! Monet could. He had muscle.

- Quote in a conversation with Vollard, along the river near Aix, 1896; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 74

- Anyone who wants to paint should read Bacon. He defined the artists as homo additus naturae.. .Bacon had the right idea, but listen Monsieur Vollard, speaking of nature, the English philosopher, [Bacon] didn't for-see our open-air school, nor that other calamity which has followed close upon its heels: open-air indoors.

- Quote in a conversation with Vollard in museum The Luxembourg, Paris 1897 - standing before the 'Olympia' of Manet; as quoted in Cézanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 36

after 1900

[edit]- You can't ask a man to talk sensibly about the art of painting if he simply doesn't know anything about it. But by God, how can he [ Zola, his childhood friend who characterized Cezanne in L'Oeuvre] dare to say that a painter is done because he has painted one bad picture? When a picture isn't realized, you pitch it in the fire and start another one.

- I work obstinately, and once in a while I catch a glimpse of the Promised Land. Am I to be like the great leader of the Hebrews, or will I really attain unto it?. .I have a large studio in the country. I can work better there than in the city. I have made some progress. Oh, why so late and so painful? Must art indeed be a priesthood, demanding that the faithful be bound to it body and soul?

- Quote from Cézanne's letter to Vollard - Aix, 9 January, 1903; as quoted in Cezanne, by Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 103

- This is what happens, unquestionably – I am positive: an optical sensation is produced in our visual organ, which leads us classify as light, half-tone or quarter-tone, the planes represented by sensations of color. [Thus the light does not exist for the painter]. As long as, inevitably, one proceeds from black to white, the former of these abstractions being a kind of point of rest both for eye and brain, we flounder about, we cannot achieve self-mastery, get possession of ourselves. During this period (I tend to repeat myself, inevitably) we turn to the admirable works [of the five great Venetian painters a. o. Titian and Tintoretto] handed down to us through the ages, in which we find comfort and support...

- Quote from Cézanne's letter to Émile Bernard, 23 December 1904; as quoted in Letters of the great artists – from Blake to Pollock, Richard Friedenthal, Thames and Hudson, London, 1963, p. 184

- Allow me to repeat what I said when you were here: deal with nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere and the cone, all placed in perspective, so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, a section of nature, or if you prefer, of the spectacle spread before our eyes by the 'Pater Omnipotens Aeterne Deus'. Lines perpendicular to that horizon give depth. But for us men, nature has more depth than surface, hence the need to introduce in our vibrations of light, represented by reds and yellows, enough blue tints to give a feeling of air.

- Quote from Cézanne's letter to Émile Bernard, 15 April 1904; as quoted in Letters of the great artists – from Blake to Pollock, Richard Friedenthal, Thames and Hudson, London, 1963, p. 180

- The point to be made clear is that, whatever may be our temperament, or our power in the presence of nature, we have to render what we actually see, forgetting everything that appeared before our own time. Which, I think, should enable the artist to express his personality to the full, be it large or small. Now that I am an old man, about seventy, the sensations of colour which produce light give rise to abstractions that prevent me from covering my canvas, and from trying to define the outlines of objects when their points of contact are tenuous and delicate; with the result that my image or picture is incomplete. For another thing, the planes become confused, superimposed; hence Neo-Impressionism (initiated by Seurat and Paul Signac, ed., where everything is outlined in black, an error which must be uncompromisingly rejected. And nature, if consulted, shows us how to achieve this aim.

- Quote from Cézanne's letter to Émile Bernard, 23 October 1905; as quoted in Letters of the great artists – from Blake to Pollock, Richard Friedenthal, Thames and Hudson, London, 1963, p. 180

- Alas! The memories that are swallowed up in the abyss of the years! I'm all alone now and I would never be able to escape from the self-seeking of human kind anyway. Now it's theft, conceit, infatuation, and now it's rapine or seizure of one's production. But Nature is very beautiful. They can't take that away from me. [in the last conversation Vollard had with Cezanne]

- Quote in a conversation in Cezanne's studio in Aix, End of 1905; as quoted in Cézanne, Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 112

- You must forgive me for continually coming back to the same thing; but I believe in the logical development of everything we see and feel through the study of nature and turn my attention to technical questions later.

- Quote of 1906 from a letter; cited in Paul Cézanne, Letters ed. John Rewald, New York, Da Capro Press, 1995, p. 313

- To my mind one does not put oneself in place of the past, one only adds a new link.

- Quote of 1906 from a letter; cited in Paul Cézanne, Letters ed. John Rewald, New York, Da Capro Press, 1995, p. 313

- As a painter I am beginning to see more clearly how to work from Nature.. .But I still can't do justice to the intensity unfolding before my eyes.

- Quote in Cezanne's letter to his son Paul, a few months before his death; as quoted in The Private Lives of the Impressionists Sue Roe; Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2006, p. 268

- I still work with difficulty, but I seem to get along. That is the important thing to me. Sensations form the foundation of my work, and they are imperishable, I think. Moreover, I am getting rid of that devil who, as you know, used to stand behind me and forced me at will to 'imitate'; he's not even dangerous any more. [one week later Cezanne died]

- Quote in Cezanne's last letter to his son Paul, Aix, 15 October 1906; as quoted in Cézanne, Ambroise Vollard, Dover publications Inc. New York, 1984, p. 112

Cézanne, - a Memoir with Conversations, (1897 - 1906)

[edit]- Quotes of Cezanne, from: Joachim Gasquet's Cézanne, - a Memoir with Conversations, (1897 - 1906); Thames and Hudson, London 1991

- Painting from nature is not copying the object, it is realizing sensations.

- p. 46, in: 'What I know or have seen of his life'

- Yes, a bunch of carrots, observed directly, painted simply in the personal way one sees it, worth more than the Ecole's everlasting slices of buttered bread, that tobacco-juice painting, slavishly done by the book? The day is coming when a single original carrot will give birth to a revolution.

- p. 68, in: 'What I know or have seen of his life'

- Here you are, put this somewhere, on your work table. You must always have this before your eyes.. .It's a new order of painting. Our Renaissance starts here.. .There's a pictorial truth in things. This rose and this white lead us to it by a path hitherto unknown to our sensibility..

- This will be my picture, the one I shall leave behind.. .But the center? Where is the center? I can't find the center.. .Tell me, what shall I group it all around? Ah, Poussin's arabesque! He knew all about that. In the London 'Bacchanal', in the Louvre 'Flora' (both are paintings of Poussin, admired by Cézanne), where does the line of the figures and the landscape begin, where does it finish.. ..It's all one. There is no center. Personally I would like something like a hole, a ray of light, an invisible sun to keep an eye on my figures, to bathe them, care them, intensify them.. ..in the middle [remark on one of his paintings ['The Bathers]']

- p. 78, in: 'What I know or have seen of his life'

- See how the light tenderly love the apricots, it takes them over completely, enters into their pulp, light them from all sides! But it is miserly with the peaches and light only one side of them.

- p. 119 (note 2), in: 'Fumées dans la campagne', Edmond Jaloux

- Personally I would like to have pupils, a studio, pass on my love to them, work with them, without teaching them anything.. .A convent, a monastery, a phalanstery of painting where one could train together.. ..but no program, no instruction in painting.. ..drawing is still alright, it doesn't count, but painting – the way to learn is to look at the masters, above all at nature, and to watch other people painting..

- p. 124, in: 'What I know or have seen of his life'

- Everything we look at disperses and vanishes. doesn't it? Nature is always the same, and yet its appearance is always changing.. .Painting must give us the flavour of nature’s eternity. Everything, you understand. So I join together nature's straying hands.. ..From all sides, here there and everywhere, I select colours, tones and shades; I set them down, I bring them together.. ..They make lines, they become objects – rocks, trees – without my thinking about them.. ..But if there is the slightest distraction, the slightest hitch, above all if I interpret too much one day, if I'm carried away today by a theory which contradicts yesterday's, if I think while I'm painting, if I meddle, then woosh!, everything goes to pieces.

- p. 148, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Art has a harmony which parallels that of nature. The people who tell you that the artist is always inferior to nature are idiots! He is parallel to it. Unless, of course, he deliberately intervenes. His whole aim must be silence. He must silence all the voices of prejudice within him, he must forget.. .And then the entire landscape will engrave itself on the sensitive plate of his being.

- p. 150, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Nature as it is seen and nature as it is felt, the nature that is there.. (he pointed towards the green and blue plain; J. G.) and the nature that is here (he tapped his forehead, J. G.) both of which have to fuse in order to endure, to live that life, half human and half divine, which is the life of art or, if you will .. the life of god. The landscape is reflected, humanized, rationalized within me. I objectivize it, project it, fix it on my canvas..

- p. 150, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- And art puts us, I believe, in a state of grace in which we experience a universal emotion in an, as it were, religious but in the same time perfectly natural way. General harmony, such as we find in colour, is located all around us.

- p. 151, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Colour is the place where our brain and the universe meet. That's why colour appears so entirely dramatic, to true painters. Look at Sainte-Victoire there [the hill, which Cézanne painted again and again] How it soars, how imperiously it thirsts for the sun!. .For a long time I was quite unable to paint Sainte-Victoire; I had no idea to go about it because, like others who just look at it, I imagined the shadow to be concave, whereas in fact it's convex, it disperses outward from the center. Instead of accumulating, it evaporates, becomes fluid, bluish, participating in the movements of the surrounding air. Just as over there to the right, on the Pilon du Roi, you can see the contrary effect, the brightness gently rocking to and fro, moist and shimmering. That's the sea.. ..That's one needs to depict. What one needs to know. That's the bath of experience, so to speak...

- p. 153, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Alas, because I'm no longer innocent. We're civilized beings. Whether we like it or not, we have the cares and concerns of classical civilization in our bones. I want to express myself clearly when I paint. In people who feign ignorance there is a kind of barbarism even more detestable than the academic kind: it's no longer possible to be ignorant today. One no longer is. We come into the world armed with facility. Facility is the death of art and we must rid ourselves of it.

- p. 155, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif': Cited in: George Pattison. God and Being: An Enquiry, (2011). p. 64

- In that Renaissance (Cellini, Tintoretto, Titian..) there was an explosion of unique truthfulness, a love of painting and form.. .Then come the Jesuits and everything is formal; everything has to be taught and learned. It required a revolution for nature to be rediscovered; for Delacroix to paint his beach at Etratat, Corot his roman rubble, Gustave Courbet his forest scenes and his waves. And how miserable slow that revolution was, how many stages it had to go through!.. .These artists had not yet discovered that nature has more to do with depth than with surfaces. I can tell you, you can do things to the surface.. ..but by going deep you automatically go to the truth. You feel a healthy need to be truthful. You'd rather strip your canvas right down than invent or imagine a detail. You want to know.

- pp. 156-157, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- ..But there is better. Simplicity, being direct. Everything else is just a game, just building castles in the sky.. .Basically I don't think of anything when I paint. I see colours. I strive with joy to convey them on to my canvas just as I see them. They arrange themselves as they choose, any old way. Sometimes that makes a picture. I'm brainless animal. Very content if I could be just that..

- p. 158-159, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Make others feel the same way about it. Without their realizing it! That's the meaning of art.. .Yes, what I'm aiming for is the logical development of what we see and feel when we observe nature; only then I'm concerned with the process, processes being for us no more than simple ways of getting the public to feel what we ourselves are feeling, and of making our point. The great artists we admire have done no more.. .Shall we have lunch?

- p. 160, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif

- ..and wanting to force nature to say things, making trees twist and rocks frown, as Gustave Doré does, or even painting it like Leonardo da Vinci, that's literature too. There's logic of colour, damn it all! The painter owes allegiance to that alone. Never to the logic of the brain; if he abandons himself to that logic, he's lost.. .Painting is first and foremost an optical affair. The stuff of our art is there, in what our eyes are thinking.. .If you respect nature, it will always unravel its meaning for you.

- p. 161, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Colour, if I may say so, is biological. Colour is alive and colour alone makes things come alive.. .Without losing any part of myself, I need to get back to that instinct, so that these colours in the scattered fields signify an idea to me, just as to them they signify a crop. Confronted by a yellow, they spontaneously feel the harvesting activity required of them, just as I, when faced with the same ripening tint..

- p. 162, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Treat nature in terms of the cylinder, the sphere, and the cone, the whole put into perspective so that each side of an object, or of a plane, leads towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth, whether a sections of nature, or, if you prefer, of the spectacle which Pater omnipotens aeterne Deus unfolds before your eyes. Lines perpendicular to this horizon give depth.. .Everything I am telling you [ Joachim Gasquet ] about - the sphere, the cone, cylinder, concave shadow – on mornings when I'm tired these notions of mine get me going, they stimulate me, I soon forget them once I start using my eyes.

- pp. 163-164, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- It's like Impressionism. They all do it at the Salons. Oh, very discreetly! I too was an Impressionist. I don't conceal the fact. Pissarro had an enormous influence on me. But I wanted to make out of Impressionism something solid and lasting like the art of the museums.

- p. 164, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- But what an eye Monet has, the most prodigious eye since painting began! I raise my hat to him. As for Courbet, he already had the image in his eye, ready-made. Monet used to visit him, you know, in his early days.. .But a touch of green, believe me, is enough to give us a landscape, just as a flesh tone will translate a face for us..

- p. 164, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- That is why, perhaps, all of us derive Pissarro. He had the good luck to be born in the West Indies, where he learned how to draw without a teacher. He told me all about it. In 1865 he was already cutting out black, bitumen, raw sienna and the ocher's. That's a fact. Never paint with anything but the three primary colours and their derivatives, he used to say me. Yes, he was the first Impressionist.

- p. 164, in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Camille Pissarro was Cézanne's 'teacher' in impressionistic landscape painting; they frequently painted together in open air.

- Monet's cliffs (at Etretat) will survive as a prodigious series, as will a hundred others of his canvases.. .He'll be in the Louvre, for sure, alongside Constable and Turner. Damn it, he's even greater. He painted the iridescence of the earth. He's painted water. Remember those Rouen cathedrals.. .But where everything slips away in these pictures of Monet's, nowadays we must insert a solidity, a framework..

- p. 165 in: 'What he told me – I. The motif'

- Degas isn't enough of a painter; he doesn't have enough of that! With a little bit of temperament one can manage to be a painter, It's enough to have a sense of art, and that sense is no doubt what the bourgeoisie fear most.. .For a painter, sensation is at the bottom of everything. I will go on repeating it forever. Procedures are not what I advocate.

- pp. 184-185 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre'

- Let's not eliminate nature. Too bad if we fail. You see, in his 'Dejeuner sur l'herbe', Manet ought to have added - I don't know what - a touch of this nobility, whatever it is in this picture that conveys heaven to our every sense. Look at the golden flow of the tall woman, the other one's back.. .They are alive and they are divine.

- p. 186 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre' [standing in the Louvre in front of the painting 'Le concert Champêtre', painted by Giorgioni (ca. 1510)

- Yes, yes, a formula that's a straitjacket.. ..not for me! All the same, he tries in vain, does Jean-Dominique [Ingres], to wring your heart with his glossy finish! I said this to Vollard, to shock him, he is very powerful! Nevertheless he [ Jean-Dominique Ingres, French classicist painter] is a damned good man.. .The most modern of the moderns. Do you know why I take my hat off to him? Because he forced his fantastic draughtsmanship down the throats of the idiots who now claim to understand it. But here there are only two: Delacroix and Courbet. The rest are scoundrels.

- p. 192 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre'

- He (Delacroix) turns David [French painter] upside down. His painting is iridescent. Seeing one Constable [famous English landscape painter, admired by French painters, then] is enough to make him understand all the possibilities of landscape, and he too sets up his easel by the sea.. .And he has a sense of human being, of life in movement, of warmth. Everything moves, every glistens. The light!.. .There is more warm light in this interior [probably: Delacroix's 'Woman of Algiers'] of his than in all of Corot's landscapes..

- p. 196 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre'

- Maybe Delacroix stands for Romanticism. He stuffed himself with too much Shakespeare and Dante, thumbed through too much Faust. His palette is still the most beautiful in France, and I tell you no one under the sky had more charm and pathos combined than he, or more vibration of colour. We all paint in his language, as you all write in Hugo's.

- p. 197 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre'

- A builder. A rough and ready plasterer. A colour grinder. He Courbet is like a Roman bricklayer. And yet he's another true painter. There's no one in this century that surpasses him. Even though he rolls up his sleeves, plugs up his ears, demolishes columns, his workmanship is classical!.. .His view was always compositional. His vision remained traditional. Like his palette-knife, he used it only out of doors. He was sophisticated and brought his work to a high finish.. .His great contribution is the poetic introduction of nature - the smell of damp leaves, mossy forest cuttings - into nineteenth century painting; the murmur of rain, woodlands shadows, sunlight moving under trees. The sea. And snow, he painted snow like no one else!

- p. 198 in: 'What he told me – II. The Louvre'

- That's my great ambition. To be sure! Every time I attack a canvas I feel convinced, I believe that something's going to come of it.. .But I immediately remember that I've always failed before. Then I taste blood.. .I never know where I am going or where I want to go with this damned profession. All the theories mess you up inside.

- p. 206 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- Until the war [between France and Germany] as you know, my life was a mess. I wasted it. It was only at l'Estaque, when (1870-1871) I thought things over, that I really understood Pissarro, a painter like myself.. .He was a determined man. I was overcome by a passion for work. It wasn't that I hadn't been working before, I was always working. But what I always missed, you know, was a comrade like you..

- p. 208 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- I'd like to combine melancholy and sunshine.. .There's a sadness in Provence which no one has expressed; Poussin would have shown it in terms of some tomb, underneath the poplars of the Alyscamps.. .I'd like to put reason in the grass and tears in the sky, like Poussin.. .You really need to see and feel your subject very clearly, and then If I express myself with distinction and power, there's my Poussin, there's my classicism..

- p. 211 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- When I'am outlining the skin of a lovely peach with soft touches of paint, or a sad old apple, I catch a glimpse in the reflections they exchange of the same mild shadow of renunciation, the same love of the sun, the same recollection of the dew.. .Why do we divide up the world? Does this reflects our egoism?.. .The prism is our first step towards God, our seven beatitudes.

- p. 220 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- Objects enter into each other.. .Chardin [French classical still-life painter] was the first to have glimpsed that and rendered the atmosphere of objects.. .Notice how a light transversal plane straddling the bridge of your nose makes the values more evident to the eye.. .Well, he noticed that before we did.. .He neglected nothing. He also perceived that whole encounter in the atmosphere of the tiniest particles, the fine dust of emotion that surrounds objects..

- p. 220 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- ..in my ideal of a good painting; there's unity. The drawing and the colour are no longer distinct; as soon as you paint you draw; the more the colours harmonize, the more precise the drawing becomes. I know that from experience. When the colour is at its richest, the form is at its fullest.

- p. 221 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

- There is, in a apple, in a head, a culminating point, and this point - in spite of the effect, the tremendous effect: shadow or light, sensations of colour - is always the one nearest to the eye. The edge of objects recede to another point placed on your horizon. This is my great principle, my conviction, my discovery. The eye must concentrate, grasp the subject, and the brain will find a means to express it..

- p. 222 in: 'What he told me – III. The Studio'

Quotes about Paul Cézanne

[edit]- sorted chronologically, by date of the quotes about Cezanne

before 1910

[edit]- ..he came to the motif twice a day [a snow scene of Auvers, Cézanne painted in the early 1870's], in the morning and the evening, in gray weather and in clear; it so happened that he often slaved away at a painting from one season to another, from one year to another, so that in the end the Spring of 1873 became the effect of snow.

- Paul Gachet (1874) as cited by John Rewald, The Paintings of Paul Cezanne, A Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. 1. publ; Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1996, p. 146.

- Like a voluptuous vision, this artificial corner of paradise has left even the most courageous gasping for breath... and Mr Cézanne merely gives the impression of being a sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens.

- Marc de Montifaud (art-critic), reviewing Cézanne's 'A Modern Olympia' in 'L'artiste', 1 May 1874; as cited in 'Under the Influence - How the art of the past informs that of the present', Jennifer Higgie; in 'OPINION - 1 OCT 2013

- This Cézanne [Still life with Compotier, Fruit and Glass, c. 1879-1882], that you ask me for is a pearl of exceptional quality and I already have refused three hundred francs for it; it is one of my most treasured possessions, and except in absolute necessity, I would give up my last shirt before the picture.

- Paul Gauguin, June 1888, in a letter to his friend Schuffenecker; as quoted in 'Impressionism: A Centenary Exhibition', Anne Distel, Michel Hoog, Charles S. Moffett, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, (New York, N.Y.) 1975, p. 56.

- It was then [c. 1873], as I remember that Paul Cézanne began to paint with vertical divisions and Papa [his father, Camille Pissarro adopted the long brush to paint in little comma's. A peasant who had watched them side by side at Auvers, remarked that 'M. Pissarro at working, made little stabs at the canvas ('il piquait'), and M. Cézanne laid on the paint like plaster ('il plaquait'). [Cézanne's painting 'Small house at Auvers' is painted with some of these vertical divisions that Lucien [the son of Camille Pissarro, and later also a painter] noted then.

- Lucien Pissarro; as cited in Pissarro, His Life and Work, ed., Ralph E. Shikes, Paula Harper, Horizon Press, 1980, p. 128.

- ..he [Cézanne] never ceased declaring that he was not making pictures, but that he was searching for a technique. Of that technique, each picture contained a portion successfully applied, like a correct phrase of a new language to be created.

- Theodore Reff in: Painting and Theory in the Final Decade, p. 37; as quoted in ; as quoted in Outside the Lines, David W. Galenson, Harvard University Press, 2001, p. 57.

- remark of a visiting painter, in 1894

- I hope that Cezanne will still be here and that he will join us, but he is so shy, so afraid of meeting new people, that I am afraid that he might let us down, even though he wants very much to meet you. How sad it is that this man hasn't had more patronage in his life! This is a true artist who has come to doubt himself far too much. He needs to be cheered up, so he was quite touched by your article.

- Claude Monet (1894), in his letter from Giverny to Gustave Geffroy, 23 November 1894; cited in: P. Michael Doran (2001), Art Conversations with Cézanne, p. 3.

- How does he Cézanne do it? He cannot put two touches of colour on a canvas without its being very good.

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1890), as quoted in Joachim Gasquet’s Cézanne, - a Memoir with Conversations, (1897 - 1906); Thames and Hudson, London 1991, p. 121.

after 1910

[edit]- It was because Cézanne could come at reality only through what he saw that he never invented purely abstract forms. Few great artists have depended more on the model. Every picture carried him a little further towards his goal—complete expression; and because it was not the making of pictures but the expression of his sense of the significance of form that he cared about, he lost interest in his work so soon as he had made it express as much as he had grasped. His own pictures were for Cézanne nothing but rungs in a ladder at the top of which would be complete expression. The whole of his later life was a climbing towards an ideal. For him every painting was a means, a step, a stick, a hold, a stepping-stone—something he was ready to discard as soon as it had served his purpose. He had no use for his own pictures. To him they were experiments. He tossed them into bushes, or left them in the open fields to be stumbling-blocks for a future race of luckless critics.

- Clive Bell, Art (1914) IV.—The Movement, I. The Debt to Cézanne, p. 199. See also Modern Art and Modernism (2018) ed., Francis Frascina, Charles Harrison, pp. 75-78.

- The Impressionists were the first [painters] to reject the absolute value of the subject and to consider its value to be merely relative.. .In Paul Cezanne's letters I notice ideas like these: 'Objects must turn, recede, and live. I wish to make something lasting from impressionism, like the art in the museums'.. .'For an impressionist, to paint after nature is not to paint the object, but to express sensations'.. .'After having looked at the old masters, one must take haste to leave them and to verify in one’s self the instincts, the sensations that dwell in us.'

- Fernand Léger (1914), Contemporary Achievements in Painting, in 'Soirées de Paris', Paris 1914; as quoted in The documents of 20th century art, Thames and Hudson Ltd, London 1973

- [E]very year [he] sent two canvases to the Salon. They were constantly refused, until, in 1882... one of his entries, a portrait, had... been accepted! Of course he got into the Salon by the back door. His friend Guillemet, who was serving on the jury, and who tried in vain to get Cézanne's canvas accepted on the second vote, had put it through pour sa charité for at the time every member of the jury had the privelage of taking into the Salon a canvas by one of his pupils, without any conditions. ...Later, in the interests of equality, the Jury was deprived of this privelage... But the painter was again to have the satisfaction of being represented in... the Universal Exposition of 1889. ...[H]ere again he was accepted through favoritism, or... by means of a "deal." The committee had importuned Monsieur Choquet to send them a... precious piece of furniture... but he made the formal condition that a canvas of Cézanne's should be exhibited... [T]he picture was "skyed" so [high] that none but the owner and the painter noticed it.

No matter; imagine Cézanne's joy at seeing a picture of his actually hung once more!- Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne (1914) Paris, Éditions G. Crès; as translated by Harold L. Van Doren in Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art (1923, 1926) pp. 67-69.

Cézanne, 1899

Cézanne, 1894-1905

Cézanne, 1898–1905

- Very few people ever had the opportunity to see Cézanne at work, because he could not endure being watched while at the easel. For one who has seen him paint, it is difficult to imagine how slow and painful his progress was on certain days. In my portrait there are two little spots of canvas on the hand which are not covered. I called Cézanne's attention to them. "If the copy I'm making in the Louvre turns out well," he replied, "perhaps I will be able tomorrow to find the exact tone to cover up those spots. Don't you see, Monsieur Vollard, that if I put something there by guesswork, I might have to paint the whole canvas over starting from that point?" The prospect made me tremble.

During the period that Cézanne was working on my portrait, he was also occupied with a large composition of nudes, begun about 1895, on which he labored almost to the end of his life.- Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne (1914) Paris, Éditions G. Crès; as translated by Harold L. Van Doren in Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art (1923, 1926) p. 126.

- [H]e was caught in a storm while working in the field. Only after having kept at it for two hours under a steady downpour did he start to make for home; but on the way he dropped exhausted. A passing laundry-wagon stopped, and the driver took him home. His old housekeeper came to the door. Seeing her master prostrate and almost lifeless, her first impulse was to run to him and give him every attention. But just as she was about to loosen his clothes, she stopped, seized with alarm. It must be explained that Cézanne could not endure the slightest physical contact. Even his son, whom he cherished above all... never dared to take his father's arm without saying, "Permit me, papa." And Cézanne, notwithstanding the affection he entertained for his son, could never resist shuddering.

Finally, fearing lest he pass away if he did not have proper care, the good woman summoned all her courage and set about to chafe his arms and legs to restore circulation, with the result that he regained consciousness without making the slightest protest—which was indeed a bad sign. He was feverish all night long.

On the following day he went down into the garden, intending to continue a study... In the midst of the sitting he fainted; the model called for help; they put him to bed, and he never left it again. He died a few days later, On October 22, 1906.- Ambroise Vollard, Paul Cézanne (1914) Paris, Éditions G. Crès; as translated by Harold L. Van Doren in Paul Cézanne: His Life and Art (1923, 1926) pp. 184-185.

- When Cézanne laid a canvas aside, it was almost always with the intention of taking it up again, in the hope of bringing it to perfection.

- Ambroise Vollard, Cezanne; New York, Dover, 1984, Chapter 8.

- Cézanne made a cylinder out of a bottle. I start from the cylinder to create a special kind of individual object. I make a bottle — a particular bottle — out of a cylinder.

- Juan Gris (1921), a response to questionnaire circulated to the Cubists by Amédée Ozenfant and Le Corbusier, editors of L'Esprit Nouveau # 5 (February 1921), pp. 533-534; trans. Douglas Cooper in Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, Juan Gris, His Life and Work (1947)

- No one will ever paint like Cezanne for example, because no one will ever have his peculiar visual gifts; or to put it less dogmatically, will anyone ever appear again with so peculiar and almost unbelievable a faculty for dividing color sensations and making logical realizations of them? Has anyone ever placed his color more reasonably with more of a sense of time and measure than he? I think not, and he furnished for the enthusiast of today new reasons for research into the realm of color for itself.

- Marsden Hartley (1928), in his article 'Art and the Personal Life', 1928; accessed online Aug. 7, 2007 on Artchive, n.p.

- It is not what the artist does that counts. But what he is. Cézanne would never have interested me if he had lived and thought like Jaques-Emile Blanche, even if the apple he had painted had been ten times more beautiful. What interests us is the anxiety of Cézanne, the teaching of Cézanne, the anguish of Van Gogh, in short the inner drama of the man. The rest is false. [Boisgeloup, winter 1934].

- Pablo Picasso, in an interview with Christian Zervos Conversation avec Picasso, in Cahiers d'Art, Vol X, 7-10, (1935), p. 173-178.

- ..[enabled] to touch the core, the essence of things. Even in as simple a subject, a great painter can achieve a majesty of vision and an intensity of feeling to which we immediately respond. [1937, referring to a still life by Cézanne and a river-sight with sandbank by Monet ]

- Giorgio Morandi, in: Giorgio Morandi, E. Roditi; p. 63

- ..my favorite artist, when I first began to paint, was actually Cézanne. Later, between 1920 – 1930, I developed a great interest in Chardin [famous for his still-life], Vermeer and Corot, too.. ..that's why you have been able to detect in my works of between 1912 – 1916 some recognizable influences of the early Paris cubists and above all, of Cézanne.

- Giorgio Morandi, in Dialogues – conversations with European Artists at Mid-century, Edouard Roditi, Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd, London, 1990, p. 106.

- While he warned his friends to avoid the influence of Gauguin, van Gogh and the neo-impressionists, Cézanne liked to speak of his former comrades, praising Renoir and especially Monet, evoking with particular tenderness the "humble and colossal" Pissarro. When he was invited by a group of Aix artists to exhibit with them in 1902 and again in 1906, Cézanne—now over sixty and acclaimed by the new generation as their undisputed leader—piously affixed to his name: pupil of Pissarro. Pissarro never learned of this tribute...

- John Rewald, History of Impressionism (1946) pp. 427-428.

- Push answers with pull and pull with push.. .At the end of his life and the height of his capacity Paul Cézanne understood color as a force of push and pull. In his pictures he created an enormous sense of volume, breathing, pulsating, expanding, contracting through his use of colors.

- Hans Hofmann (1948), in "Search for the Real in the Visual Arts", (1948) p. 44.

- I was with Cézanne for a long time, and now naturally I am with Picasso.

- Arshile Gorky (1940s), in Gorky Memorial Exhibition, Schwabacher pp. 28 (his quote in 1940's)

- Cézanne's painting is strictly painting, and its value is immense; but Van Gogh's painting has the Outsider's characteristic: it is a laboratory refuse of a man who treated his own life as an experiment in living; it faithfully records moods and developments of vision on the manner of a Bildungsroman.

- Colin Wilson (1956), in The Outsider, p. 103.

- The whole Renaissance tradition is antipathic to me. The hard-and-fast rules of perspective which it succeeded in imposing on art were a ghastly mistake which it has taken four centuries to redress; Paul Cézanne and after him Picasso and myself can take a lot of credit for this.. ..scientific perspective forces the objects in a picture to disappear away form the beholder instead of bringing them within his reach as painting should.

- Georges Braque (1957), in an interview: The Observer, by John Richardson - 1 December 1957

- ..the light suggests no particular time of day or night [in the paintings of Cézanne]; it is not appropriated from morning or afternoon, sunlight or shadow.

- Clyfford Still (c. 1958), in Abstract Expressionism, Davind Anfam, Thames and Hudson Ltd London, 1990; p. 145.

- But I find, because of modern painting, that things which couldn't be seen in terms of painting, things you couldn't paint.. ..it is not that you paint them, bit is the connection. I imagine that Cézanne, when he painted a ginger pot with apples, must have been very grotesque in his day, because a still life was something set up of beautiful things. It may be very difficult, for instance, to put a Rheingold bottled beer on the table and a couple of glasses and a package of Lucky Strike [cigarets]. I mean, you know, there are certain things you cannot paint at a particular time, and it takes a certain attitude how to see those things, in terms of art.

- Willem de Kooning, (March 1960), in an interview with David Sylvester, edited for broadcasting by the BBC first published in 'Location', Spring 1963; as quoted in Interviews with American Artists, by David Sylvester; Chatto & Windus, London 2001, p. 54.

- Artists have never worked with the model – just with the painting. What you [G. R. Swenson, the interviewer] are really saying is that an artist like Cézanne transforms what we think the painting ought to look like into something he thinks it ought to look like. He’s working with paint, not nature; he’s making a painting, he’s forming. I think my work is different from comic strips – but I wouldn't call it transformation; I don’t think that whatever is meant by it is important to art. What I do is form, whereas the comic strip is not formed in the sense I'm using the word; the comics have shapes but there has been no effort to make them intensely unified. The purpose is different, one intends to depict and I intend to unify.

- Roy Lichtenstein (1963), in 'What is Pop Art? Interviews with eight painters', G. R. Swenson, in 'Art News 67', November 1963, pp. 25-27.

- When I want to speak about why I am doing the same thing now, which is squares, for – how long? – 19 years. Because there is no final solution in any visual formulation. Although this may be just a belief on my part, I have some assurances that that is not the most stupid thing to do, through Cezanne whom I consider as one of the greatest painters. From Cézanne we have, so the historians tell us – 250 paintings of 'Mont St. Victoire'. But we know that Cézanne has left in the fields often more than he took home because he was disappointed with his work. So we may conclude he did many more than 250 of the same problem.

- Josef Albers (1968), in 'Oral history interview with Josef Albers', conducted by Sevim Fesci, 22 June – 5 July 1968, for the 'Archives of American Art', Smithsonian Institution, n.p.

- Who we are and how we appear to the world is always filled with paradox. Being ourselves is like Cézanne painting a landscape — he who was always tentative, always questioning, never fully sure but always attempting to respond honestly to his 'little sensations' as he called them.

- F. David Peat (2002), in From Certainty to Uncertainty

- Picasso is taking Cézanne's elements - the cone, cylinder and sphere - into Cubism. Matisse is taking Cézanne's interest in the wholeness and the clarity of figures. They're taking almost opposite interpretations of what they see in Cézanne: Picasso is understanding it as decomposition, and Matisse is understanding it as composition.

- John Elderfield (MoMA-curator and Matisse scholar) as quoted in 'Matisse & Picasso, Paul Trachtman, Smithsonian Magazine, February 2003, p. 4.

- [Matisse] worked his way through the different modes of vision employed in nineteenth-century avant-guard painting, starting with the impressionists and then moving on to Seurat, van Gogh, Gauguin, and especially Cézanne, who was to remain the greatest and longest-lasting source of inspiration to him. As early as 1899, Matisse made great sacrifices in order to buy a small but powerful Cézanne, Three Bathers, and he was the first of the younger avant-guard artists to absorb the radically new kind of pictorial thought that Cézanne's painting embodied. Cézanne was... Matisse said, "a sort of god of painting."

- Jack Flam (2003) in Matisse and Picasso: The Story of Their Rivalry and Their Friendship (2003) pp. 4-5.

- Cézanne paints solids, but we reach them beyond the canvas.

- Muriel Rukeyser The Life of Poetry (1949)

- It used to be agreed that painting was a visual, music an auditory art. R. G. Collingwood, in his brilliant The Principles of Art, goes on to tell how Cézanne came then, and began to paint like a blind man. His rooms are full of volumes: these tables, the people in these chairs are bulks which have been felt with the hands. These trees are not what trees look like, they are what trees feel like.

- Muriel Rukeyser The Life of Poetry (1949)

External links

[edit]- Paul Cézanne (1915) ed., Ambroise Vollard @Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) Gallica (National Library of France) online.

- Cézanne, Paul @WebMuseum.

- The Bather @MoMA Online Collection