Muriel Rukeyser

Muriel Rukeyser (15 December 1913 – 12 February 1980) was an American poet and political activist, most famous for her poems about equality, feminism, social justice, and Judaism.

Quotes

[edit]- "I speak to you. You speak to me. Is that fragile?"

- "Waterlily Fire", IV: 'Fragile', in Waterlily Fire: Poems 1935-1962 (1962), and in Out of Silence: Selected Poems, ed. Kate Daniels (1994), p. 120

- What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.

- attributed in Medicine Stories by Aurora Levins Morales (1998)

U.S. 1 (1938)

[edit]

Here is your road, tying

you to its meanings: gorge, boulder, precipice.

The Book of the Dead

[edit]- These are roads to take when you think of your country

and interested bring down the maps again,

phoning the statistician, asking the dear friend,

reading the papers with morning inquiry.- "The Road"

- Here is your road, tying

you to its meanings: gorge, boulder, precipice.

Telescoped down, the hard and stone-green river

cutting fast and direct into the town.- "The Road"

- What do you want — a cliff over a city?

A foreland, sloped to sea and overgrown with roses?

These people live here.- "Gauley Bridge"

- This is to be a summary poem of the life of the Atlantic coast of this country, nourished by the communications which run down it. Gauley Bridge is inland, but it was created by theories, systems, and workmen from many coastal sections — factors which are, in the end, not regional or national. Local images have one kind of reality. U.S. 1 will, I hope, have that kind and another too. Poetry can extend the document.

- Note, on "The Book of the Dead"

To be a Jew in the Twentieth Century (1944)

[edit]

Death of the spirit, the stone insanity.

Accepting, take full life. Full agonies…

To be a Jew in the twentieth century

Is to be offered a gift. If you refuse,

Wishing to be invisible, you choose

Death of the spirit, the stone insanity.

Accepting, take full life. Full agonies:

Your evening deep in labyrinthine blood

Of those who resist, fail, and resist: and God

Reduced to a hostage among hostages.The gift is torment.

- The whole and fertile spirit as guarantee

For every human freedom, suffering to be free,

Daring to live for the impossible.

The Life of Poetry (1949)

[edit]

- In time of crisis, we summon up our strength.

Then, if we are lucky, we are able to call every resource, every forgotten image that can leap to our quickening, every memory that can make us know our power. And this luck is more than it seems to be: it depends on the long preparation of the self to be used.

In time of the crises of the spirit, we are aware of all our need, our need for each other and our need for our selves. We call up, with all the strength of summoning we have, our fullness.- Introduction

- In this moment when we face horizons and conflicts wider than ever before, we want our resources, the ways of strength. We look again to the human wish, its faiths, the means by which the imagination leads us to surpass ourselves.

If there is a feeling that something has been lost, it may be because much has not yet been used, much is still to be found and begun.

Everywhere we are told that our human resources are all to be used, that our civilization itself means the uses of everything it has — the inventions, the histories, every scrap of fact. But there is one kind of knowledge — infinitely precious, time-resistant more than monuments, here to be passed between the generations in any way it may be: never to be used. And that is poetry.- Chapter One : The Fear of Poetry

Poetry is, above all, an approach to the truth of feeling, and what is the use of truth!

How do we use feeling?

How do we use truth!However confused the scene of our life appears, however torn we may be who now do face that scene, it can be faced, and we can go on to be whole.

If we use the resources we now have, we and the world itself may move in one fullness. Moment to moment, we can grow, if we can bring ourselves to meet the moment with our lives.- Chapter One : The Fear of Poetry

- Poetry is not; or seems not to be. But it appears that among the great conflicts of this culture, the conflict in our attitude toward poetry stands clearly lit. There are no guards built up to hide it. We call see its expression, and we can see its effects upon us. We can see our own conflict and our own resource if we look, now, at this art, which has been made of all the arts the one least acceptable.

Anyone dealing with poetry and the love of poetry must deal, then, with the hatred of poetry, and perhaps even Ignore with the indifference which is driven toward the center. It comes through as boredom, as name-calling, as the traditional attitude of the last hundred years which has chalked in the portrait of the poet as he is known to this society, which, as Herbert Read says, "does not challenge poetry in principle it merely treats it with ignorance, indifference and unconscious cruelty."

Poetry is foreign to us, we do not let it enter our daily lives.

- A poem does invite, it does require. What does it invite? A poem invites you to feel. More than that: it invites you to respond. And better than that: a poem invites a total response.

This response is total, but it is reached through the emotions. A fine poem will seize your imagination intellectually — that is, when you reach it, you will reach it intellectually too — but the way is through emotion, through what we call feeling.- Chapter One : The Fear of Poetry, p. 8

- A poem invites you to feel. More than that: it invites you to respond. And better than that: a poem invites a total response. This response is total, but it is reached through the emotions. A fine poem will seize your imagination intellectually- that is, when you reach it, you will reach it intellectually too-but the way is through emotion, through what we call feeling. (Chapter One, p 11)

- I speak, then, of a poetry which tends where form tends, where meanings tend. This will be a poetry which is concerned with the crises of our spirit, with the music and the images of these meanings. It will also be a poetry of meeting-places, where the false barriers go down. For they are false. (Chapter One, p 20)

- The universe of poetry is the universe of emotional truth. Our material is the way we feel and the way we remember. (p 23)

- Art is action, but it does not cause action: rather, it prepares us for thought. Art is intellectual, but it does not cause thought: rather, it prepares us for thought. Art is not a world, but a knowing of the world. Art prepares us. (p 25)

- Art and nature are imitations, not of each other, but of the same third thing both images of the real, the spectral and vivid reality that employs all means. If we fear it in art, we fear it in nature, and our fear brings it on ourselves in the most unanswerable ways. (p 26)

- The use of truth is its communication. (p 27)

- The meanings of poetry take their growth through the interaction of the images and the music of the poem. The music is not the rhythm, which is a representation of life, alone. The music involves the interplay of the sounds of words, the length of the sequences, the keeping and breaking of rhythms, and the repetition and variation of syllables unrhymed and rhymed. It also involves the play of ideas and images.

- p. 31

- The statement of ideas in a poem may have to do with logic. More profoundly, it may be identified with the emotional progression of the poem, in terms of the music and images, so that the poem is alive throughout.

Another, more fundamental statement in poetry, is made through the images themselves — those declarations, evocative, exact, and musical, which move through time and are the actions of a poem.- p. 31

- The poetic image is not a static thing. It lives in time, as does the poem. Unless it is the first image of the poem, it has already been prepared for by other images; and it prepares us for further images and rhythms to come. Even if it is the first image of the poem, the establishment of the rhythm prepares us — musically — for the music of the image. And if its first word begins the poem, it has the role of putting into motion all the course of images and music of the entire work, with nothing to refer to, except perhaps a title.

- p. 32

- Many of our poems are such monuments. They offer the truths of outrage and the truths of possibility.

- p. 66

- Belief has its structures, and its symbols change. Its tradition changes. All the relationships within these forms are inter-dependent. We look at the symbols, we hope to read them, we hope for sharing and communication. Sometimes it is there at once, we find it before the words arrive, as in the gesture of John Brown, or the communication of a great actor-dancer, whose gesture and attitude will tell us before his speech adds meaning from another source. Sometimes it rises in us sleeping, evoked by the images of dream, recognized in the blood. The buried voices carry a ground music; they have indeed lived the life of our people. In times of perversity and stress and sundering, it may be a life inverted, the poet who leaps from the ship into the sea; on the level of open belief, it will be the life of the tribe. In subjugated peoples, the poet emerges as prophet.

- p. 96

- There are ways in which poetry reaches the people who, for one reason or another, are walled off from it. Arriving in diluted forms, serving to point up an episode, to give to a climax an intensity that will carry it without adding heaviness, to travel toward the meaning of a work of graphic art, nevertheless poetry does arrive. And in the socially accepted forms, we may see the response and the fear, expressed without reserve, since they are expressed during enjoyment which has all the sanctions of society.

Close to song, poetry reaches us in the music we admit: the radio songs that flood our homes, the juke-boxes, places where we drink and eat, the songs of work for certain occupations, the stage-songs we hear as ticketed audience.- p. 109

- We sit here, very different each from the other, until the passion arrives to give us our equality, to make us part of the play, to make the play part of us.

- p. 126

- The continuity of film, in which the writer deals with a track of images moving at a given rate of speed, and a separate sound-track which is joined arbitrarily to the image-track, is closer to the continuity of poetry than anything else in art. But the heaviness of the collective work on a commercial film, the repressive codes and sanctions, unspoken and spoken, the company-town feeling raised to its highest, richest, most obsessive-compulsive level in Hollywood, puts the process at the end of any creative spectrum farthest from the making of a poem.

At the same time, almost anything that can be said to make the difficulties of poetry dissolve for the reader, or even to make the reader want to deal with those "difficulties," can be said in terms of film. These images are like the action sequences of a well-made movie — a good thriller will use the excitement of timing, of action let in from several approaches, of crisis prepared for emotionally and intellectually, so that you can look back and recognize the way of its arrival; or, better, feel it coming until the moment of proof arrives, meeting your memory and your recognition.

The cutting of films is a parable in the motion of any art that lives in time, as well as a parable in the ethics of communication.- p. 150

- In time of the crises of the spirit, we are aware of all of need, our need for each other and our need for ourselves. We call up our fullness; we turn, and act. We begin to be aware of correspondences, of the acknowledgement in us of necessity, and of the lands.

And poetry, among all this — where is there a place for poetry?

If poetry as it comes to us through action were all we had, it would be very much. For the dense and crucial moments, spoken under the stress of realization, full-bodied and compelling in their imagery, arrive with music, with our many kinds of theatre, and in the great prose. If we had these only, we would be open to the same influences, however diluted and applied. For these ways in which poetry reaches past the barriers set up by our culture, reaching toward those who refuse it in essential presence, are various, many-meaning, and certainly — in this period — more acceptable. They stand in the same relation to poetry as applied science to pure science.- p. 169; part of this statement is also used in the "Introduction"

- The creation of a poem, or mathematical creation, involves so much sense of arrival, so much selection, so much of the desire that makes choice — even though one or more of these may operate in the unconscious or partly conscious work-periods before the actual work is achieved — that the questions raised are very pertinent. . . . The poet chooses and selects and has that sense of arrival as the poem ends; he is expressing what it feels like to arrive at his meanings. If he has expressed that well, his reader will arrive at his meanings. The degree of appropriateness of expression depends on the preparing. By preparing I mean allowing the reader to feel the interdependences, the relations, within the poem.

These inter-dependences may be proved, if you will allow the term, in one or more ways: the music by which the syllables resolve may lead to a new theme, as in a verbal music, or to a climax, a key-relationship which makes — for the moment — an equilibrium; the images may have established their own progression in such a way that they serve to mark the poem’s development; the tensions and attractions between the poem’s meanings may mark its growth, as they must if the poem is to achieve its form.

A poem is an imaginary work, living in time, indicated in language. It is and it expresses; it allows us to express.- p. 181

- The identified spirit, man and woman identified, moves toward further identifications. In a time of long war, surrounded by the images of war, we imagine peace. Among the resistances, we imagine poetry. And what city makes the welcome, in what soil do these roots flourish? For our concern is with sources. The sources of poetry are in the spirit seeking completeness. If we look for the definitions of peace, we will find, in history, that they are very few. The treaties never define the peace they bargain for: their premise is only the lack of war. The languages sometimes offer a choice of words: in the choice is illumination. In one long-standing language there are two meanings for peace. These two provide a present alternative. One meaning of peace is offered as "rest, security." This is comparable to our "security, adjustment, peace of mind." The other definition of peace is this: peace is completeness. It seems to me that this belief in peace as completeness belongs to the same universe as the hope for the individual as full-valued. In what condition does poetry live? In all conditions, sometimes with honor, sometimes underground. That history is in our poems.

- p. 209

- A society in motion, with many overlapping groups, in their dance. And above all, a society in which peace is not lack of war, but a drive toward unity.

- p. 210

- Always our wars have been our confessions of weakness.

- p. 211

- the making of a poem is the type of action which releases aggression. Since it is released appropriately, it is creation. For the last time here, I wish to say that we will not be saved by poetry. But poetry is the type of the creation in which we may live and which will save us.

- p. 211

- The world of this creation, and its poetry, is not yet born. The possibility before us is that now we enter upon another time, again to choose. Its birth is tragic, but the process is ahead: we must be able to turn a time of war into a time of building.

- p. 213

- The great ideas are always emerging, to be available to all men and women. And one hope of our lives is the communication of these truths.

- p. 213

- To be against war is not enough, it is hardly a beginning.

- p. 213

- We are against war and the sources of war. We are for poetry and the sources of poetry.

They are everyday, these sources, as the sources of peace are everyday, infinite and commonplace as a look, as each new sun.- p. 213

- As we live our truths, we will communicate across all barriers, speaking for the sources of peace. Peace that is not lack of war, but fierce and positive. We hear the saints saying: Our brother the world. We hear the revolutionary: Dare we win? All the poems of our lives are not yet made. We hear them crying to us, the wounds, the young and the unborn-we will define that peace, we will live to fight its birth, to build these meanings, to sing these songs. Until the peace makes its people, its forests, and its living cities; in that burning central life, and wherever we live, there is the place for poetry. And then we will create another peace. ** p. 214

- Experience taken into the body, breathed-in, so that reality is the completion of experience, and poetry is what is produced. And life is what is produced.

To stand against the idea of the fallen world, a powerful and destructive idea overshadowing Western poetry. In that sense, there is no lost Eden, and God is the future. The child walled-up in our life can be given his growth. In this growth is our security.- p. 221

- How can I look back and not speak of the stupid learning about birth? Of the stupid learning that people make love, and how it seemed the reason for all things, the intimacy of my wondering, the illumination that — to an adolescent — was the cause for life around me, the reason why the unhappy people I knew did not kill themselves?

- p. 222

The Speed of Darkness (1968)

[edit]

Waking with sleeping, ourselves with each other,

Ourselves with ourselves. We would try by any means

To reach the limits of ourselves, to reach beyond ourselves,

To let go the means, to wake.

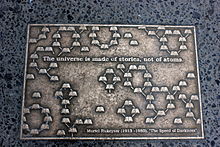

- The Universe is made of stories, not of atoms.

- "The Speed of Darkness"; this line is sometimes misquoted as "The Universe is made of stories not atoms."

- I lived in the first century of world wars.

Most mornings I would be more or less insane.- "Poem"

- Slowly I would get to pen and paper,

Make my poems for others unseen and unborn.

In the day I would be reminded of those men and women,

Brave, setting up signals across vast distances,

considering a nameless way of living, of almost unimagined values.- "Poem"

- We would try to imagine them, try to find each other,

To construct peace, to make love, to reconcile

Waking with sleeping, ourselves with each other,

Ourselves with ourselves. We would try by any means

To reach the limits of ourselves, to reach beyond ourselves,

To let go the means, to wake.- "Poem" — these lines are among those quoted on the The Pacifist Memorial

The Gates (1976)

[edit]

How shall we tell each other of the poet?'

How shall we venture home?

How shall we tell each other of the poet?

How can we meet the judgment on the poet,

or his execution? How shall we free him?How shall we speak to the infant beginning to run?

All those beginning to run?- "The Gates"

- O for God's sake

they are connected

underneath.- "Islands"

“The Education of a Poet” (1976)

[edit]- One opens, yes, and one's life keeps opening, and poets have always known that one's education has no edges, has no end, is not separated out and cannot be separated out in any way, and is full of strength because one refuses to have it separated out.

- it was suggested to me in my adolescence, it would be a good idea if I married a doctor, and when he was out on housecalls I could write my poems. Now of course we have no housecalls and we have women poets-the culture has changed to that extent.

- The people in the fine apartment houses insisted that Hooverville be destroyed because it spoiled their view. It was clear to a growing child that the terrible, murderous differences between the ways people lived were being upheld all over the city, that if you moved one block in any direction you would find an entirely different order of life.

- I was told by friends, when it was a matter of deciding to go ahead and have a child, that I would have to choose between the child and poetry, and I said no. I was not going to make that choice; I would choose both.

- How old were you when you knew that there were living poets? Do you remember? In this culture a great many people don't know that there are living poets, or didn't know when I was growing up.

- There are the questions of love and religion that have to enter, along with the social bonds between us, into everything we do.

- I've always thought of two kinds of poems: the poems of unverifiable facts, based in dreams, in sex, in everything that can be given to other people only through the skill and strength by which it is given; and the other kind being the document, the poem that rests on material evidence.

- at college there was so much more freedom, and an access to materials and to people who were more than I had thought people could be. It was there that everything opened again, but I left college because my father had gone bankrupt and could not afford to have a daughter at Vassar.

- I don't believe that poetry can save the world. I do believe that the forces in our wish to share something of our experience by turning it into something and giving it to somebody: that is poetry. That is some kind of saving thing, and as far as my life is concerned, poetry has saved me again and again.

Interview (February 1978)

[edit]In Poetry in Person: Twenty-five Years of Conversation with America's Poets edited by Alexander Neubauer (2011)

- In rewriting, I have tried always to strengthen the sound structure and to make a dense fabric, of sound, of fact, of reality and truth.

- The movement of meaning is surely the music of poetry. There isn't any music as we mean music, but there is that movement in the body and the soul, if you like. And one longs for it; it is a deep pleasure and a deep life to us, and there is this union of a physical life and a mental life that comes to us in poetry, and the physical life is bound up with sound in that way. The movement of our breathing is why we take pleasure in hearing poets read, even though most poets are abominable readers, as you know.

- it seems to me that the invitation of poetry is to bring your whole life to this moment, this moment is real, this moment is what we have, this moment in which we face each other, and if a poem is any damn good at all, it invites you to bring your whole life to that moment, and we are good poets inasmuch as we bring that invitation to you, and you are good readers inasmuch as you bring your whole life to the reading of the poem.

- Anger I would like to talk about, too. All my life I have protested in anger against what was happening, in rebellion, about wanting to make a new society and change the world, but I know underneath that I am a person who makes things much more than a person who protests. And I finally came to the point of saying, "I will protest all my life but every time I protest, I will make a poem, or I will plant, or I will feed children, or I will try to help a building, I will make something."

Quotes about Rukeyser

[edit]

- Muriel Rukeyser gave me the notion, the promise of what art could be....Nothing stopped her, neither war nor fear, shame or confusion. She knew fear but did not give into it. She went through fear as she went through hatred, coming out the other side into hope and I took her life as an ideal.... It was from her that I learned that art-poetry, fiction, story-art is not product, art is life itself. The use of poetry, she said, is usable truth and such was the nature of her passionate courage she made me believe her. I rank Muriel Rukeyser with Walt Whitman, the essential American poet, democratic at the level of hope. Lifesaving. Indispensable. And even now when I feel myself overcome with my own fears and confusion, she draws me out every time.... She is life-saving still.

- Dorothy Allison, blurb for The Life of Poetry

- Muriel Rukeyser's first poem in her first book of poetry published in 1935 begins: "Breathe in experience, breathe out poetry." And in her tribute to the German graphic artist Käthe Kollwitz, Rukeyser asked: "What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?" And answered: "The world would split open." This is not the poetry of contrivance; this is the poetry of naming, of philosophy, framing a set of ideas through which to interpret our realities as women.

- Bettina Aptheker Tapestries of Life: Women's Work, Women's Consciousness, and the Meaning of Daily Experience (1989)

- Muriel Rukeyser is an essential and defining voice. Few poets have combined rigorous perspective with ethical witness in the way her work manages to do. Few poets manage to love the world in as challenging and musical a language as she provides.

- Eavan Boland blurb for The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (1978)

- the writers Muriel Rukeyser and Ruth Seid (pen name: Jo Sinclair), two strongly Jewish-identified, anti-racist white lesbians.

- Elly Bulkin Yours in Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Antisemitism and Racism (1984)

- This book ranks among essential works of twentieth century literature; it is saving, challenging. In The Life of Poetry Rukeyser examines the ways in which poetry can revive democracy and improve the quality of life for the people of the United States, and for poets, artists, and creative individuals everywhere...The Life of Poetry is not a book of criticism nor is it a literary treatise. It is a book that breaks boundaries and assumptions about the place of literature and the arts in American life. Rukeyser suggests that by living with the senses and the imagination open, living with poetry, human beings can prosper and attain peace. Remarkably, Rukeyser's words are as necessary and provocative now as when the book was first published, in 1949.

- Jan Freeman in The Life of Poetry (1968 edition)

- Rukeyser was the most courageous poet of her brilliant generation. Her example and her greatest works are indispensable to our understanding of America, and to our own ability to say the truth.

- Reginald Gibbons blurb for The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (1978)

- one of the twentieth century's germinal writers.

- Marilyn Hacker blurb for The Life of Poetry

- An "American genius," our "twentieth-century Whitman." Anne Sexton and Erica Jong both referred to Muriel Rukeyser as "the mother of everyone."

- Anne F. Herzog and Janet E. Kaufman in their Introduction to How Shall We Tell Each Other of the Poet? : The Life and Writing of Muriel Rukeyser (2001), p. xv

- In a time like this we need all the wisdom and nourishment we can get, and we have gathered today to share these things. I invoke one of the wisest, bravest voices of our century: the late Muriel Rukeyser, poet, activist, Jew, lesbian, relentless fighter for freedom...Muriel Rukeyser, again, wrote in 1944, "To be a Jew in the 20th century is to be offered a gift." Let us seize this gift.

- Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz "Swords Into Plowshares: Jews For Middle East Peace" in The Issue is Power (1992)

- An awfully long time ago and a very short time ago, in one of the early books, Muriel wrote that "poems flowered from the bone." I always think of that line because it somehow seems to be both a prophecy and a summing up of all the work that has taken place in the books that came later.

- Pearl London 1978 interview in Poetry in Person: Twenty-five Years of Conversation with America's Poets edited by Alexander Neubauer (2011)

- Muriel Rukeyser unspools one of the most passionate arguments I've ever read for the notion that art creates meeting places, that poetry creates democracy.

- One of the most important poets of our time.... Her originality, her genius, her courage illuminate our century.

- Sharon Olds blurb for The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (1978)

- Muriel Rukeyser was always a political person and a sad loss for some of us-for all of us, but particularly for those who knew her. She was a total poet, totally involved in literature, and she took a beating as a woman and as a poet who was not part of the elite that began to develop after the forties knocked the thirties on their head. She and somebody like Meridel Le Sueur were doubly wounded. They were wounded as women by their own political men-something like black women are-and wounded again by the literary elite, who were for the birds. But on the other hand Muriel lived very deeply in literature and with literary people. She knew them from an early age; she was close to Mexican poets, American poets, and she was political at the same time. When she got to be president of PEN she went to Korea even though she could hardly walk by then; she was very brave. [Rukeyser died of a heart attack in 1980.] So there are people who manage to do the whole thing.

- 1992 interview in Conversations with Grace Paley edited by Gerhard Bach and Blaine Hall (1997)

- I'd say the other major influences in late adolescence were Muriel Rukeyser and William Butler Yeats. Muriel was very important to me, as a writer who wrote honestly, passionately, and well about being a woman, as a writer with politics, as a writer whose work was written to be said aloud.

- Marge Piercy interview in My Life, My Body (2015)

- Sisyphus is not, finally, a useful image. You don't roll some unitary boulder of language or justice uphill; you try with others to assist in cutting and laying many stones, designing a foundation. One of the stonecutter-architects I met was Muriel Rukeyser, whose work I had begun reading in depth in the 1980s. Through her prose Rukeyser had engaged me intellectually; her poetry, however, in its range and daring, held me first and last. "Her Vision" is a tribute to the mentorship of her work.

- Adrienne Rich, Forward to Arts of the Possible (2000)

- The radical poet Muriel Rukeyser said long ago, "The universe is made of stories, not of atoms." Choosing the stories you, yourself, are made of is crucial work as we enter this unfinished story of how human beings responded to the greatest emergency our species has ever faced.

- Rebecca Solnit Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility (2023)

- Muriel Rukeyser loved poetry more than anyone I've ever known. She also believed it could change us, move the world.

- Alice Walker, in promotional remark for the 1996 edition of The Life of Poetry (1949)

- American self-confidence, Emerson argued, should be grounded not in a narrow chauvinistic claim about the superiority of the American way but rather in a mature affirmation of America's gifts to the world as well as candid acknowledgment of the "most un-handsome part of our condition." Cheap American patriotism not only reflects an immaturity and insecurity, he warned, but also is an adolescent defense mechanism that reveals a fear to engage the world and learn from others. Narrow nationalism is a handmaiden of imperial rule, he argues-it keeps the populace deferential and complacent. Hence it abhors critics and dissenters like Emerson who unsettle and awaken the people. His shining example of democratic intellectual work is a challenge to us today. This challenge has been taken up through the years by a stream of Emersonian voices-from Walt Whitman to William James, Gertrude Stein. W. E. B. Du Bois, and Muriel Rukeyser...Muriel Rukeyser in her classic The Life of Poetry laid bare the democratic aspirations of exploited working people in their creative expressions.

- Cornel West, Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism (2004)

- Muriel Rukeyser, who opened much of the forbidden territory where poets can now move with ease. Here, for a new generation, the full range of the capacious poet who gave twentieth-century women's poetry its mottoes and its most audacious exemplar, and poetry of witness and moral passion its most ardent and urgent American voice.

- Eleanor Wilner blurb for The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (1978)

"Muriel Rukeyser" by Adrienne Rich

[edit]in Arts of the Possible (2001)

- To enter her work is to enter a life of tremendous scope, the consciousness of a woman who was a full actor and creator in her time. But in many ways Muriel Rukeyser was beyond her time-and seems, at the edge of the twenty-first century, to have grasped resources we are only now beginning to reach for: connections between history and the body, memory and politics, sexuality and public space, poetry and physical science, and much else. She spoke as a poet, first and foremost; but she spoke also as a thinking activist, biographer, traveler, explorer of her country's psychic geography. It's no exaggeration to say that in the work of Muriel Rukeyser we discover new and powerful perspectives on the culture of the United States in the twentieth century, "the first century of world wars," as she called it.

- From a young age she seems to have understood herself as living in history-not as a static pattern but as a confluence of dynamic currents, always changing yet faithful to sources, a fluid process that is constantly shaping us and that we have the possibility of shaping. The critic Louise Kertesz, a close reader of Rukeyser and her context, notes that "no woman poet makes the successful fusion of personal and social themes in a modern prosody before Rukeyser." She traces a North American white women's tradition in Lola Ridge, Marya Zaturenska and Genevieve Taggard, all born at the end of the nineteenth century and all struggling to desentimentalize the personal lyric and to write from urban, revolutionary, and working-class experience.

- Any sketch of her life suggests the vitality of a woman who was by nature a participant, as well as an inspired observer, and the risk-taking of one who trusted the unexpected, the fortuitous, without relinquishing choice or sense of direction.

- Rukeyser's work attracted slashing hostility and scorn (of a kind that suggests just how unsettling her work and her example could be) but also honor and praise. Kenneth Rexroth, patriarch of the San Francisco Renaissance, called her "the best poet of her exact generation." At the other end of the critical spectrum, for the London Times Literary Supplement she was "one of America's greatest living poets."

- In her lifetime she was a teacher of many poets, and readers of poetry, and some scientists paid tribute to her vision of science as inseparable from art and history. But she has largely been read and admired in pieces-in part because most readers come to her out of the very separations that her work, in all its phases, steadfastly resists.

- We call her prose "poetic" without referring to her own definitions of what poetry actually is an exchange of energy, a system of relationships.

- Rukeyser was unclassifiable, thus difficult for canon-makers and anthologists. She was not a "left wing" poet simply, though her sympathies more often than not intersected with those of the organized left, or the various lefts, of her time. Her insistence on the value of the unquantifiable and unverifiable ran counter to mainstream "scientific attitudes" and to plodding forms of materialism. She explored and valued myth but came to recognize that mythologies can rule us unless we pierce through them, that we need to criticize them in order to move beyond them. She wrote at the age of thirty-one: "My themes and the use I have made of them have depended on my life as a poet, as a woman, as an American, and as a Jew." She saw the self-impoverishment of assimilation in her family and in the Jews she grew up among; she also recognized the vulnerability and the historical and contemporary "stone agonies" endured by the Jewish people. She remained a secular visionary with a strongly political sense of her Jewish identity. She wrote out of a woman's sexual longings, pregnancy, night-feedings, in a time when it was courageous to do so, especially as she did it-unapologetically, as a big woman alive in mind and body, capable of violence and despair as well as desire.

- I never came to know her well; New York has a way of sweeping even the like-spirited into different scenes. But there was an undeniable sense of female power that came onto any platform along with Muriel Rukeyser. She carried her large body and strongly molded head with enormous pride, and stood with presence behind her words. Her poems ranged from political witness to the erotic to the mordantly witty to the visionary. Even struggling back from a stroke, she appeared inexhaustible. She was, in the originality of her nature and achievement, as much an American classic as Melville, Whitman, Dickinson, Du Bois, or Hurston.

Jane Cooper, Forward to The Life of Poetry (1949)

[edit]- Elsewhere her heroes are Willard Gibbs, the mathematical physicist, Albert Pinkham Ryder, painter of the sea, John Jay Chapman, man of letters, Ann Burlak, labor organizer, Charles Ives, composer on American themes; and John Brown (abolitionist) and Wendell Willkie, political visionaries who seemed, at their historical moments, to fail; Houdini and Lord Timothy Dexter, anomalies in any pantheon. How many of their stories are familiar to us, even now? Of all these she made biographies, in verse or prose or mixed media-the series of "Lives" that would occupy her to the end. All were Americans. Of the first five she pointed out, in 1939, that they were also New Englanders, "whose value to our generation is very great and only partly acknowledged." She never wanted to write extensively about anyone who had already received his or her due, and it's worth noting how rarely any of her subjects is literary. For years she worked on a book, now lost, on Franz Boas, anthropologist who studied North American indigenous tribes. Only much later would she turn to several non-Americans, the last being Thomas Hariot, Elizabethan navigator, mathematician, naturalist, astronomer, who published the first Brief and True Report of Raleigh's Virginia, the "Indians" who lived there, and our native plants and animals.

- One of her favorite assignments was to ask everyone to complete the sentence "I could not tell...." For in what we cannot say to anyone, in our most secret conflicts, lie curled, she believed, our inescapable poems.

- Rukeyser proposes-following D'Arcy Thompson now as well as Gibbs-that the great poems are always organic, as forms in nature are organic. They grow by "clusters and combinations," through time; they find their true direction as they proceed; and they never stand still but "fly through, and over" any attempt to pin them down by analysis. They include material from the unconscious and welcome the unknown. More, "the work that a poem does is a transfer of human energy," from the poet through the poem to the fully responsible and responsive witness/reader. And now she takes a gigantic leap, tying the poet forever to the society and historical moment she or he shares with others: "I think human energy may be defined as consciousness, the capacity to make change in existing conditions."

- rarely will you encounter a mind or imagination of greater scope.

- she was a visionary. One of the great, necessary poets of our country and century, whose value to the present generation is only beginning to be acknowledged, like Whitman she was a poet of possibility.

- she was a "she-poet." As she told her interviewer in 1972, "Anything I bring to this is because I am a woman. And this is the thing that was left out of the Elizabethan world, the element that did not exist. Maybe, maybe, maybe that is what one can bring to life."