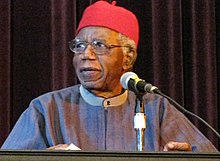

Chinua Achebe

Appearance

Chinua Achebe (November 16, 1930 – March 21, 2013) was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic. His first novel, Things Fall Apart (1958), is the most widely read book in modern African literature.

Quotes

[edit]- The world is like a Mask dancing. If you want to see it well, you do not stand in one place.

- Arrow of God (1988)

- For an African writing in English is not without its serious setbacks. He often finds himself describing situations or modes of thought which have no direct equivalent in the English way of life. Caught in that situation he can do one of two things. He can try and contain what he wants to say within the limits of conventional English or he can try to push back those limits to accommodate his ideas … I submit that those who can do the work of extending the frontiers of English so as to accommodate African thought-patterns must do it through their mastery of English and not out of innocence.

- Quoted by Kalu Ogbaa, Understanding Things Fall Apart (1999), Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-30294-7.

Things Fall Apart (1958)

[edit]- (Page numbers in parentheses refer to the 1969 Fawcett Premier edition.)

- Proverbs are the palm-oil with which words are eaten.

- Chapter 1

- When the moon is shining the cripple becomes hungry for a walk.

- Chapter 2 (p. 14)

- We shall all live. We pray for life, children, a good harvest and happiness. You will have what is good for you and I will have what is good for me. Let the kite perch and let the egret perch too. If one says no to the other, let his wing break.

- Chapter 3 (p. 22)

- A proud heart can survive general failure because such a failure does not prick its pride. It is more difficult and more bitter when a man fails alone.

- Chapter 3 (p. 27)

- The Ibo people have a proverb that when a man says yes his chi says yes also. Okonkwo said yes very strongly, so his chi agreed. And not only his chi but his clan too, because it judged a man by the work of his hands.

- Chapter 4 (p. 29)

- But he was not the man to go about telling his neighbors that he was in error. And so people said he had no respect for the gods of the clan. His enemies said that his good fortune had gone to his head.

- Chapter 4 (p. 32)

- Even the village rain-maker no longer claimed to be able to intervene. He could not stop the rain now, just as he would not attempt to start it in the heart of the dry season, without serious danger to his own health.

- Chapter 4 (p. 35)

- No matter how prosperous a man was, if he was unable to rule his women and his children (and especially his women) he was not really a man.

- Chapter 7 (p. 52)

- "When did you become a shivering old woman," Okonkwo asked himself, "you, who are known in all the nine villages for your valor in war? How can a man who has killed five men in battle fall to pieces because he has added a boy to their number? Okonkwo, you have become a woman indeed."

- Chapter 8 (pp. 62–63)

- "You sound as if you question the authority and the decision of the Oracle, who said he should die."

"I do not. Why should I? But the Oracle did not ask me to carry out its decision." [...]

"The Earth cannot punish me for obeying her mesenger," Okonkwo said. "A child's fingers are not scalded by a piece of hot yam which its mother puts into its palm."- Chapter 8 (p. 64)

- After such treatment it would think twice before coming again, unless it was one of the stubborn ones who returned, carrying the stamp of their mutilation--a missing finger or perhaps a dark line where the medicine man's razor had cut them.

- Chapter 9 (p. 75)

- And when, as on that day, nine of the greatest masked spirits in the clan came out together it was a terrifying spectacle.

Okonkwo's wives, and perhaps other women as well, might have noticed that the second egwugwu had the springy walk of Okonkwo. And they might also have noticed that Okonkwo was not among the titled men and elders who sat behind the row of egwugwu. But if they thought these things they kept them to themselves. The egwugwu with the springy walk was one of the dead fathers of the clan.- Chapter 10 (p. 85)

- "Beware Okonkwo!" she warned. "Beware of exchanging words with Agbala. Does a man speak when a god speaks? Beware!"

- Chapter 11 (p. 95)

- The land of the living was not far removed from the domain of the ancestors. There was coming and going between them, especially at festivals and also when an old man died, because an old man was very close to the ancestors. A man's life from birth to death was a series of transition rites which brought him nearer and nearer to his ancestors.

- Chapter 13 (p. 115)

- If the clan did not exact punishment for an offense against the great goddess, her wrath was loosed on all the land and not just on the offender. As the elders said, if one finger brought oil it soiled all the others.

- Chapter 13 (p. 118)

- It was like beginning life anew without the vigor and enthusiasm of youth, like learning to become left-handed in old age.

- Chapter 14 (pp. 120–121)

- "We have heard stories about white men who make the powerful guns and the strong drinks and took slaves away across the seas, but no one thought the stories were true." [said Obierika]

"There is no story that is not true," said Uchendu. "The world has no end, and what is good among one people is an abomination with others. We have albinos among us. Do you not think that they came to our clan by mistake, that they have strayed from their way to a land where everybody is like them?"- Chapter 15 (p. 130)

- Chielo, the priestess of Agbala, called the converts the excrement of the clan, and the new faith was a mad dog that had come to eat it up.

- Chapter 16 (p. 133)

- "Let us give them a portion of the Evil Forest. They boast about victory over death. Let us give them a real battlefield in which to show their victory." [...] They offered them as much of the Evil Forest as they cared to take. And to their great amazement the missionaries thanked them and burst into song.

- Chapter 17 (p. 139)

- Okonkwo was popularly called the "Roaring Flame." As he looked into the log fire he recalled the name. He was a flaming fire. How then could he have begotten a son like Nwoye, degenerate and effeminate? [...]

He sighed heavily, and as if in sympathy the smoldering log also sighed. And immediately Okonkwo's eyes were opened and he saw the whole matter clearly. Living fire begets cold, impotent ash. He sighed again, deeply.- Chapter 17 (p. 143)

- The white man is very clever. He came quietly with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.

- Chapter 20 (p. 162)

- As a man danced so the drums were beaten for him.

- Chapter 22 (p. 170)

- Eneke the bird was asked why he was always on the wing and he replied: "Men have learned to shoot without missing their mark and I have learned to fly without perching on a twig."

- Chapter 24 (p. 203)

- Whenever you see a toad jumping in broad daylight, then know that something is after its life.

- Chapter 24 (p. 186)

- In the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa he had learned a number of things. One of them was that a District Commissioner must never attend to such undignified details as cutting a hanged man from the tree. Such attention would give the natives a poor opinion of him. In the book which he planned to write he would stress that point. [...] One could almost write a whole chapter on him. Perhaps not a whole chapter but a reasonable paragraph, at any rate.

- Chapter 25 (p. 191)

No Longer at Ease (1960)

[edit]- (Page numbers in parentheses refer to the 1969 Fawcett Premier edition.)

- A man who lived on the banks of the Niger should not wash his hands with spittle.

- Chapter 1 (p. 17)

- Real tragedy is never resolved. It goes on hopelessly forever. Conventional tragedy is too easy. The hero dies and we feel a purging of the emotions. A real tragedy takes place in a corner, in an untidy spot, to quote W. H. Auden.

- Chapter 5 (pp. 43–44)

- You cannot plant greatness as you plant yams or maize. Who ever planted an iroko tree — the greatest tree in the forest? You may collect all the iroko seeds in the world, open the soil and put them there. It will be in vain. The great tree chooses where to grow and we find it there, so it is with the greatness in men.

- Chapter 5 (p. 57)

- If one finger brings oil it soils the others.

- Chapter 7 (p. 75)

- A man to whom you do a favor will not understand if you say nothing, make no noise, just walk away. You may cause more trouble by refusing a bribe than by accepting it.

- Chapter 9 (p. 87)

- When there is a big tree small ones climb on its back to reach the sun.

- Chapter 10 (p. 95)

Arrow of God (1964)

[edit]- Although he was still only a child it looked as though the deity had already marked him out as his future Chief. Even before he had learnt to speak more than a few words he had been strongly drawn to the god’s ritual.

- Chapter 1 (P.4)

- When a handshake goes beyond the elbow we know it has turned to another thing.

- Chapter 1 (p.13)

- We have no quarrel with Ulu. He is still our protector, even though we no longer fear Abam warriors at night. But I will not see with these eyes of mine his priest making himself lord over us. My father told me many things, but he did not tell me that Ezeulu was king in Umuaro. Who is he, anyway? Does anybody here enter his compound through the man’s gate? If Umuaro decided to have a king we know where he would come from. Since when did Umuachala become head of the six villages? We all know that it was jealousy among the big villages that made them give the priesthood to the weakest. We shall fight for our farmland and for the contempt Okperi has poured on us. Let us not listen to anyone trying to frighten us with the name of Ulu. If a man says yes his chi also says yes: And we have all heard how the people of Aninta dealt with their deity when he failed them. Did they not carry him to the boundary between them and their neighbors and set fire on him? I salute you

- Chapter two

- I have traveled in Olu and I have traveled in Igbo, and I can tell you there is no escape from the white man. He has come. When Suffering knocks at your door and you say there is no seat for him, he tells you not to worry because he has brought his own stool. The white man is like that. Before any of you here was old enough to tie the cloth between the legs I saw with my own eyes what the white man did to Abame. Then I knew there was no escape. As daylight chases away darkness so will the white man drive away all our customs. I know that as I say it now it passes by your ears, but it will happen. The white man has power which comes from the true God and it burns like fire. This is the God about Whom we preach every eighth day.

- Chapter eight

- A man does not speak a lie to his son,” he said. “Remember that always. To say My father told me is to swear the greatest oath

- Chapter nine

- The man was a complete nonentity until we crowned him, and now he carries on as though he had been nothing else all his life. It’s the same with Court Clerks and even messengers. They all manage to turn themselves into little tyrants over their own people. It seems to be a trait in the character of the negro

- Chapter ten

- a man should hold his compound together, not plant dissension among his children

- Chapter twelve

- The man who brings ant-infested faggots into his hut should not grumble when lizards begin to pay him a visit

- Chapter twelve

Man of the People (1966)

[edit]- He looked as bright as a new shilling in his immaculate white robes.

- Chapter 4 (P.36)

- We had all accepted things from white skins that none of us would have brooked from our own people.

- Chapter 4 (p.41)

- A man of worth never gets up to unsay what he said yesterday.

- Chapter 5

- In Chief Nanga’s company it was impossible not to be merry.

- Chapter 6 (P.58)

- What mattered was that a man had treated me as no man had a right to treat another—not even if he was master and the other slave; and my manhood requires that I made him pay for his insult in full measure.

- Chapter 8 (p.73)

- That’s all they cared for,’ [Max] said with a solemn face. ‘Women, cars, landed property. But what else can you expect when intelligent people leave politics to illiterates like Chief Nanga?

- Chapter 8 (p.73)

Chike and the River (1966)

[edit]- At first Onitsha looked very strange to Chike. He could not say who was a thief or kidnapper and who was not. In Umuofia every thief was known, but here even people who lived under the same roof were strangers to one another.

- Page 7

- After the incident of the leopard skin Chike lost some of his eagerness for crossing the Niger. He did not see how he could obtain one shilling without stealing or begging.

- Page 23

- The largest sum of money he had ever had at one time was threepence.

- Page 33

- Then the stranger went away and Mr. Nwaba retired to his room. Chike did not give much thought to the incident at the time. But he was to remember it later.

- Page 62

- In his joy, he said again, ‘Thank you, sir.’ The man did not reply; he was talking to his friend again, with a cigarette in his mouth.

- Page 65

- So Chike’s adventure on the River Niger brought him close to danger and then rewarded him with good fortune. It also exposed Mr. Peter Nwaba, the rich but miserly trader. For it was he who had led the other thieves.

- Page 88

Beware Soul Brother and Other Poems (1972)

[edit]- Praise bounteous providence if you will that grants even an ogre a tiny glow-worm tenderness encapsulated in icy caverns of a cruel heart or else despair for in the very germ of that kindred love is lodged the perpetuity of evil.

- By immediately identifying his people as “men of soul” .

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 1

- Measure out / [their] joys and agonies / too, our long, long passion week / in paces of the dance”

- "Beware Soul Brother", Lines 2-5

- A dead end nor total loss.

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 8

- Lying in wait for the people’s land and resources.

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 16

- He calls the ground where men return in death a place of “safety” and “strength” .

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 32

- He warns them not to become “disinherited”.

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 35

- Lame foot in the air.

- "Beware Soul Brother", Line 35

Girls at War and Other Stories (1973)

[edit]- They led and he followed blindly, his heavy chest heaving up and down in silent weeping ... it was the worst kind of madness, deep and tongue-tied.

- From "The Madman" (pg. 10)

- We did not ask him for money yesterday; we shall not ask him tomorrow. But today is our day; we have climbed the iroko tree and would be foolish not to take down all the firewood we need.

- From "The Voter" (pg. 16)

- I don't believe anybody will be so unlike other people that they will be unhappy when their sons are engaged to marry.

- From "Marriage Is a Private Affair" (pg. 22)

- People create stories create people; or rather stories create people create stories.

- From the story "The Sacrificial Egg"

- When suffering knocks at your door and you say there is no seat for him, he tells you not to worry because he has brought his own stool.

- From the story "The Voter"

- War is war. The strong will always crush the weak. The only difference is that in the process some have made a lot of money and others a lot of misery.

- From the story "Vengeful Creditor"

- In his mind, he could see the ravages of war: destruction, suffering, hunger, and the grotesque faces of men turned beasts by the bitterness of combat.

- From the story "Girls at War"

- An Image of Africa:Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness is the published and amended version of the second Chancellor's Lecture given by Nigerian writer and academic Chinua Achebe at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in February 1975.

- A Conrad student informed me in Scotland that Africa is merely a setting for the disintegration of the mind of Mr. Kurtz. Which is partly the point. Africa as setting and backdrop which eliminates the African as human factor. Africa as a metaphysical battlefield devoid of all recognizable humanity, into which the wandering European enters at his peril.

- The real question is the dehumanization of Africa and Africans which this age-long attitude has fostered and continues to foster in the world. And the question is whether a novel which celebrates this dehumanization, which depersonalizes a portion of the human race, can be called a great work of art.

- It always surprised him, he went on to say, because he never had thought of Africa as having that kind of stuff, you know.

- [Expressing the painful irony of encountering an older man who thinks literature and history are not only interchangeable, but don't actually exist for an entire continent.

- The earth seemed unearthly.

- Author illustrates the antithesis of white Europe and racism.

- Conrad saw and condemned the evil of imperial exploitation but was strangely unaware of the racism on which it sharpened its iron tooth.

- Author's praise for the main character in the novel]\

- We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet.

- A certain enormous buck nigger encountered in Haiti fixed my conception of blind, furious, unreasoning rage, as manifested in the human animal to the end of my days.

- Chinua Achebe is depicting the first time Conrad encountered an African American

Conversation with James Baldwin (1981)

[edit]Anthologized in Conversations with James Baldwin edited by Louis H. Pratt and Fred L. Standley (1989)

- The total life of man is reflected in his art. And so when people come to us and say, "Why are you... you artist so political?" I don't know what they are talking about. Because art is political. And further more I'd say this, that those who tell you "Do not put too much politics in your art," are not being honest. If you look very carefully you will see that they are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is. And what they are saying is not don't introduce politics. What they are saying is don't upset the system. They are just as political as any of us. It's only that they are on the other side. Now in my enthusiasm, art cannot be on the side of the oppressor.

- What art tries to do is domesticate whatever is around and press it into the service of man. Morality is basic to the nature of art.

- we are not gladiators. But there is something we are committed to of fundamental importance, something everybody should be committed to. We are committed to the process of changing our position in the world. This is what our literature is about. There is a certain position assigned to me in the world, assigned to him [Baldwin] in the world, and we are saying we are not satisfied with that position. This is important to me-to everybody. I think you see it is important to me. You may not see that it is important to you but it is. We want to create the new man. Mankind tries all kinds of ways, all kinds of solutions; some of them leading that far and no farther and it is wise that we try something else. We have followed your way and it seems there is a little problem at this point. And so we are offering a new aesthetic. There is nothing wrong with that...Picasso did that. In 1904 he saw that Western art had run out of breath so he went to the Congo-the dispised Congo-and brought out a new art. Don't mind what he was saying before he died: that much is entirely his business. But he borrowed something which saved his art. And we are telling you what we think will save your art. We think we are right, but even if we are wrong it doesn't matter. It couldn't be worse than it is now.

- Well there is an assumption there that Conrad's...Heart of Darkness is great art and I don't accept that. Great art flourishes on problems or anguish or prejudice. But the role of the writer must be very clear. The writer must not be on the side of oppression. In other words there must be no confusion. I write about prejudice; I write about wickedness; I write about murder, I write about rape: but I must not be caught on the side of murder or rape. It is as simple as that.

- A number of very young people in Kenya have adopted the Marxist analysis of society. And I cannot quarrel with that. But I can't help feeling at the same time... that my own aesthetic definition, which I gave earlier on, would be a little uneasy about the narrowing of things to a point where we no longer accept the truth of the Ibo proverb that "Where something stands, something else will stand beside it," and that we become like the people we are talking about the single-mindedness which leads to totalitarianism of all kinds, to fanaticism of all kinds. And I can't help the feeling that somehow at the base, art and fanaticism are not loggerheads. And so I don't dismiss the Marxist interpretation. I think it is valid in its way. But when somebody says "I am the way, the truth, and the light.... "Now my own religion, the religion of my people says something else. It says, "You may worship one god to perfection and another god will kill you." Wherever something is, something else also is. And I think it is important that whatever the regimes are saying that the artist keeps himself ready to enter the other plea. Perhaps it's not tidy perhaps we are contradicting ourselves. But one of your poets has said, "Do I contradict myself? Very well."

Anthills of the Savannah (1987)

[edit]- [W]hatever you are is never enough; you must find a way to accept something, however small, from the other to make you whole and to save you from the mortal sin of righteousness and extremism. (p. 154)

- The guilty suffers; the sufferer is guilty. As for the righteous, those whose arms are straight, they will always prosper!

- Don't disparage the day that still has an hour of light in its hand.

- As the saying goes, the unexamined life is not worth-living.

- My people have a saying which my father often used. A man whose horse is missing will look everywhere even in the roof.

- Those who mismanage our affairs would silence our criticism by pretending they have facts not available to the rest of us. Our best weapon against them is not to marshal facts, of which they are truly managers, but passion. Passion is our hope and strength.

- That we may accept a limitation on our actions but never, under no circumstances, must we accept restriction on our thinking.

- I wouldn't put myself under the democratic dictatorship even of angels and archangels.

- Do your people have a proverb about a man looking for something inside the bag of a man looking for something?

- Aha! Come to think of it, that might explain the insistence of the oppressed that the oppressor must not be allowed to camouflage his appearance or confuse the poor by stealing and masquerading in their clothes. Perhaps it is the demand of that primitive integrity of the earth... Or, who knows, it might also be something less innocent (for the earth does have its streak of peasant cunning) - an insistence that your badge of privilege must never leave your breast, nor your coat of many colours your back... so that... on the wrathful day of reckoning... you will be as conspicuous as a peacock!

Home and Exile (2000)

[edit]- In the end I began to understand. There is such a thing as absolute power over narrative. Those who secure this privilege for themselves can arrange stories about others pretty much where, and as, they like. Just as in corrupt, totalitarian regimes, those who exercise power over others can do anything.

- In the end I began to understand. There is such a thing as absolute power over narrative. Those who secure this privilege for themselves can arrange stories about others pretty much where, and as, they like. Just as in corrupt, totalitarian regimes, those who exercise power over others can do anything. They can bring out crowds of demonstrators whenever they need them.

- The Igbo people of Southern Nigeria are more than ten million strong and must be accounted one of the major peoples of Africa. Conventional practice would call them a tribe, but I no longer follow that convention. I call them a nation

- The Igbo nation in precolonial times was not quite like any nation most people are familiar with. It did not have the apparatus of centralized government but a conglomeration of hundreds of independent towns and villages each of which shared the running of its affairs among its menfolk according to title, age, occupation, etc.; and its women folk who had domestic responsibilities as well as the management of the scores of four-day and eight-day markets that bound the entire region and its neighbours in a network of daily exchange of goods and news, from far and near.

- The dispossession that caused my shrillness is in retreat though the marks of its pillage are still everywhere. I can see, in spite of them, that I have come a long way.

- It began to dawn on me that although fiction was undoubtedly fictitious it could also be true or false, not with the truth or falsehood of a news item but as to its disinterestedness, its intention, its integrity.

The Education of a British-Protected Child (2009)

[edit]- We cannot trample upon the humanity of others without devaluing our own. The Igbo, always practical, put it concretely in their proverb Onye ji onye n'ani ji onwe ya: "He who will hold another down in the mud must stay in the mud to keep him down.

- ...when we are comfortable and inattentive, we run the risk of committing grave injustices absentmindedly.

- Africa is people" may seem too simple and too obvious to some of us. But I have found in the course of my travels through the world that the most simple things can still givwe us a lot of trouble, even the brightest among us: this is particularly so in matters concerning Africa.

- I do not see that it is necessary for any people to prove to another that they build cathedrals or pyramids before they can be entitled to peace and safety.

- Paradoxically, a saint like [Albert] Schweitzer can give one a lot more trouble than King Leopold II, villain of unmitigated guilt, because along with doing good and saving African lives Schweitzer also managed to announce that the African was indeed his brother, but only his junior brother.

- The point in all this is that language is a handy whipping boy to summon and belabor when we have failed in some serious way. In other words, we play politics with language, and in so doing conceal the reality and the complexity of our situation from ourselves and from those foolish enough to put their trust in us.

- It is appropriate that we celebrate Martin Luther King, a man who struggled so valiantly to restore humanity to the oppressed and the oppressor.

- Some people flinch when you talk about art in the context of the needs of society thinking you are introducing something far too common for a discussion of art. Why should art have a purpose and a use? Art shouldn't be concerned with purpose and reason and need, they say. These are improper. But from the very beginning, it seems to me, stories have indeed been meant to be enjoyed, to appeal to that part of us which enjoys good form and good shape and good sound.

- There is a moral obligation, I think, not to ally oneself with power against the powerless.

- People from different parts of the world can respond to the same story if it says something to them about their own history and their own experience.

- Every generation must recognize and embrace the task it is peculiarly designed by history and by providence to perform.

- Writing has always been a serious business for me. I felt it was a moral obligation. A major concern of the time was the absence of the African voice. Being part of that dialogue meant not only sitting at the table but effectively telling the African story from an African perspective - in full earshot of the world.

- The triumph of the written word is often attained when the writer achieves union and trust with the reader, who then becomes ready to be drawn into unfamiliar territory, walking in borrowed literary shoes so to speak, toward a deeper understanding of self or society, or of foreign peoples, cultures, and situations.

- There was another epidemic that was not talked about much, a silent scourge—the explosion of mental illness: major depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, manic-depression, personality disorders, grief response, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, etc.—on a scale none of us had ever witnessed.

Quotes about Chinua Achebe

[edit]- Camara Laye’s The Dark Child and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart because they gave me a glorious shock of recognition. Until I read them, I was not consciously aware that people who looked like me could exist in books. I grew up in a Nigerian university town, and all the books I read before then were foreign children’s books with white characters doing unfamiliar things.

- I do reread novels I love, like Chinua Achebe’s “Arrow of God,” to remind myself of what fiction can do.

- When I read Things Fall Apart which is about an Ibo tribe in Nigeria, a tribe I never saw, a system-to put it that way or a society, the rules of which were a mystery to me, I recognized everybody in it. And that book was about my father. How we got over I don't know, we did!"

- 1981 interview in Conversations with James Baldwin edited by Louis H. Pratt and Fred L. Standley (1989)

- Achebe is a great writer. He is the father of our English literature. You can't take that away from him. His work is highly original. When I was doing my degree here, I used Arrow of God, which I think is his best work. But the critics seem to think everything should be like Things Fall Apart. Everytime you want to read Achebe, you feel you want to study it as literature. You don't pick it up as though you want to enjoy the literature. That is why for a very, very long time, if you went to the African Writers Series, you had the feeling that this is not for the common people.

- Buchi Emecheta In Interviews with Writers of the Post-Colonial World edited by Feroza Jussawalla and Reed Way Dasenbrock (1992)

- I rank Achebe very highly, especially his Arrow of God, and I consider it a tragedy that he has had to live under such disturbed conditions and writes so little.

- 1979 interview in Conversations with Nadine Gordimer edited by Nancy Topping Bazin and Marilyn Dallman Seymour (1990)

- He has begun to resuscitate and reinstate the past, the precolonial era. I'm thinking of Arrow of God, which to my mind is perhaps the best novel to come out of Africa. I think it is an absolutely wonderful novel. And if you look at that novel, it really has almost nothing to do with the impact of the white man. It is about black life, black civilization, before the period of conquest. The period of conquest is just on the horizon, so to speak. But there are not many people who have tackled that kind of theme. There are not many black writers who have done it yet.

- 1979 interview in Conversations with Nadine Gordimer edited by Nancy Topping Bazin and Marilyn Dallman Seymour (1990)

- Chinua Achebe was a real education for me, a real education.

- 1986 interview in Conversations with Toni Morrison edited by Danille K. Taylor-Guthrie (1994)

External links

[edit]

- and the River

- Things Fall Apart quotes analyzed; study guide with themes, characters, multimedia, teacher resources

- Arrow of God quotes

- No Longer at Ease quotes

Categories:

- Academics from Nigeria

- Novelists from Nigeria

- Essayists from Nigeria

- Short story writers from Nigeria

- Children's authors

- Philosophers

- Literary critics

- Educators from Nigeria

- Activists from Nigeria

- 1930 births

- 2013 deaths

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Brown University faculty

- Political activists

- Poets from Nigeria