Intellect

Intellect is a term used in studies of the human mind, and refers to the ability of the mind to come to correct conclusions about what is true or real.

Quotes

[edit]- Rabbi Barash emphasized that in the Talmud, the Golem was considered a dumb klutz because he was literal-minded, could not speak and had no “sechel,” or intellect. “If in school,” he said, “you didn’t use your brains, the teacher would say, ‘Stop behaving like a golem.’”

- Manis Barash in “Hard Times Give New Life to Prague’s Golem”, by Dan Bilefsky, New York Times, (May 10, 2009).

- Mad, adj. Affected with a high degree of intellectual independence.

- Ambrose Bierce The Devil's Dictionary (1911)

- He, therefore, who fixes a limit of any kind to his intellectual attainments dwarfs himself, and cramps the growth of that mind given to us by the Creator, and capable of indefinite expansion.

- William H. Crogman, "The Importance of Correct Ideals" (1892), in Talks for the Times (1896), p. 282

- Whoever prefers the material comforts of life over intellectual wealth is like the owner of a palace who moves into the servants’ quarters and leaves the sumptuous rooms empty.

- Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, Aphorisms, D. Scrase and W. Mieder, trans. (Riverside, California: 1994), p. 53

- Character is higher than intellect.… A great soul will be strong to live, as well as strong to think.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "The American Scholar" (August 31, 1837), in Nature: Addresses and Lectures (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1849), pp. 94–95

- Thou living ray of intellectual fire.

- William Falconer, The Shipwreck (1762), Canto I, line 104

- The intellect is prompted by nature to comprehend the whole breadth of being.… Under the concept of truth it knows all, and under the concept of the good it desires all.

- Marsilio Ficino, Five Questions Concerning the Mind (1495), as translated by J. L. Burroughs, in The Renaissance Philosophy of Man (1948)

If someone asks us which of these is more perfect, intellect or sense, the intelligible or the sensible, we shall promise to answer promptly, if he will first give us an answer to the following question. You know, my inquiring friend, that there is some power in you which has a notion of each of these things—a notion, I say, of intellect itself and of sense, of the intelligible and the sensible. This is evident, for the same power which compares these to each other must at that time in a certain manner see both. Tell me, then, whether a power of this kind belongs to intellect or sense? ...

Sense, as you yourself have shown, can perceive neither itself nor intellect and the objects of intellect; whereas intellect knows both. ... Therefore, intellect is not only more perfect than sense but is also, after perfection itself, in the highest degree perfect.

- Marsilio Ficino, Five Questions Concerning the Mind (1495), as translated by J. L. Burroughs, in The Renaissance Philosophy of Man (1948), pp. 203-204

- "What is the Unpardonable Sin?" asked the lime-burner; and then he shrank farther from his companion, trembling lest his question should be answered. "It is a sin that grew within my own breast," replied Ethan Brand, standing erect with a pride that distinguishes all enthusiasts of his stamp. "A sin that grew nowhere else! The sin of an intellect that triumphed over the sense of brotherhood with man and reverence for God, and sacrificed everything to its own mighty claims!

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, "Ethan Brand" (1850) originally titled "The Unpardonable Sin" in The Snow-Image, and Other Twice-Told Tales

- Intellectual life has a certain spontaneous character and inner determination. It has also a peculiar poise of its own, which I believe is established by a balance between two basic qualities in the intellectual’s attitude toward ideas—qualities that may be designated as playfulness and piety.

- Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1974), p. 27

- Intellect needs to be understood not as some kind of claim against the other human excellences for which a fatally high price has to be paid, but rather as a complement to them without which they cannot be fully consummated.

- Richard Hofstadter, Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1974) p. 46

- The truth of practical intellect is understood not as conformity to an extramental being but as conformity to a right desire; the end is no longer to know what is, but to bring into existence that which is not yet.

- Jacques Maritain, "Action: The Perfection of Human Life", Sewanee Review, Vol. LVI, No. 1 (Winter 1948), p. 3

- The practical intellect knows for the sake of action. From the very start its object is not Being to be grasped, but human activity to be guided and human tasks to be achieved. It is immersed in creativity. To mould intellectually that which will be brought into being, to judge about ends and means, and to direct or even command our powers of execution—these are its very life.

- Jacques Maritain, Creative Intuition in Art and Poetry (New York: New American Library, 1953), pp. 32–33

- The inherent contradiction between condemning the intellect as invalid and incapable of reaching truth, and using that same intellect to make the condemnation, seems, strangely, not to occur to those who hold this derogatory view of the intellect.

- Norah Michener, Maritain on the Nature of Man (Hull, Canada: Éditions "L'Éclair", 1955), p. 2

- Psychology, speaking for emotion and instinct, has reduced intellect to impotence over life. Metaphysics has subordinated it to will. Bergson and his followers have charged it with falsehood and issued a general warning against its misrepresentations; while with pragmatists and instrumentalists it has sunk so low that it is dressed in livery and sent to live in the servant's quarters. It is against this last indignity in particular that I wish to speak a word of protest, to the end that the intellect may be accorded full rights within the community of human activities and interests.

- Ralph Barton Perry, "The Integrity of the Intellect," Harvard Theological Review, vol. 13, no. 3, July 1920, pp.220-221

- My own opinion is that youthfulness of feeling is retained, as is youthfulness of appearance, by constant use of the intellect.

- Margaret Elizabeth Sangster, Winsome Womanhood (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1900), Ch. XXI: "New Studies", p. 167

- The worst of what is called good society is not only that it offers us the companionship of people who are unable to win either our praise or our affection, but that it does not allow us to be that which we naturally are; it compels us, for the sake of harmony, to shrivel up, or even alter our shape altogether. Intellectual conversation, whether grave or humorous, is only fit for intellectual society; it is downright abhorrent to ordinary people, to please whom it is absolutely necessary to be commonplace and dull. This demands an act of severe self-denial; we have to forfeit three-fourths of ourselves in order to become like other people. No doubt their company may be set down against our loss in this respect; but the more a man is worth, the more he will find that what he gains does not cover what he loses, and that the balance is on the debit side of the account; for the people with whom he deals are generally bankrupt—that is to say, there is nothing to be got from their society which can compensate either for its boredom, annoyance and disagreeableness, or for the self-denial which it renders necessary.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Counsels and Maxims, T. B. Saunders, trans., § 9

- Intellect is invisible to the man who has none.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Counsels and Maxims, T. B. Saunders, trans., § 23

- The march of intellect is proceeding at quick time; and if its progress be not accompanied by a corresponding improvement in morals and religion, the faster it proceeds, with the more violence will you be hurried down the road to ruin.

- Robert Southey, Sir Thomas More, or Colloquies on the Progress and Prospects of Society (1824). London: John Murray, 1829, Vol. II, Colloquy XIV: "The Library", p. 361

- It is the expensiveness of our pleasures that makes the world poor and keeps us poor in ourselves. If we could but learn to find enjoyment in the things of the mind, the economic problems would solve themselves.

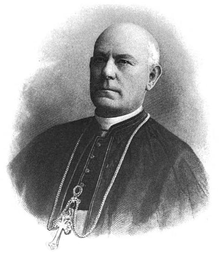

- John Lancaster Spalding, Aphorisms and Reflections (1901)