John Gunther

Appearance

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an American journalist and author.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-selling Inside U.S.A. in 1947. However, he is now best known for his memoir Death Be Not Proud, on the death of his beloved teenage son, Johnny Gunther, from a brain tumor.

Quotes

[edit]1930s

[edit]Inside Europe (1936)

[edit]- New York: Harper & Brothers, hardcover. First published in 1936, this book was subsequently revised and republished numerous times.

- It would be naïve in the extreme to dismiss General Francisco Franco as a villain or a butcher. He is a creature of his caste, a product of his moral environment, and a fairly typical example of it. He has been commended for intelligence and courage, and he possesses social grace and charm. Beyond doubt, as he sees patriotism, he is a patriot. He is an idealist too. But let it be remembered that he started the war, and if he loses it, he will be a man like such tragic figures as Wrangel and Deniken, who helped create what they sought to destroy. It is Franco- and what he represents- who knit Leftist Spain into a competent unity; if communism comes to Spain, General Franco will have been its accoucheur.

- 1938 Edition, New York: Harper & Brothers, hardcover, p. 177

Inside Asia (1939)

[edit]- New York: Harper & Brothers, hardcover.

- This book is for Johnny, who suggested it

- Dedication

- If you look at a map of the British Empire, neatly colored pink by tradition- an odd color to choose, when you come to think about it- the temptation is great to consider it as a unit, as something uniform. As matter of fact the British Empire, wih its 485,000,000 people, its 13,290,000 square miles, is very far from being uniform. Its vast "mixture of growths and accumulations" is by no means governed by a single law.

The Empire includes dominions like Canada and Australia, which are self-governing, sister states of Britain virtually independent since the Statute of Westminster, except for the common bondage of the Crown. It includes the colossal subcontinent of India, itself sub-divided into British India and princely states, which we shall deal with soon. It includes some crown colonies which are administrative dictatorships, and some which have constitutions and legislatures. It includes "free states" like Eire, mandated territories like Palestine, protectorates like the hinterland of Aden, condominums like the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, territory held jointly with France like the New Hebrides, and political curiosities such as Bhutan or Sarawak which fit into no normal categories. There are even regions ruled by charter companies like the old East India Company.- p. 315

- A common denominator is, of course, imperialism. The root reason why the colonies exist is exploitation. The British are there to get something out of being there. But exploitation is paid for by a variety of services; the British bribe the natives whom they exploit to enjoy the process of exploitation as a double reward: first, attention to such matters as public health, public order, education; second, by gradual training of the people toward self-government. No British colony is a slave state, though political mastery may be complete. In most British colonies the eventual result of British imperialism is held to be freedom from the strictures of that imperialism. Obviously the process thus envisaged is an extremely gradual one. Development of self-governing institutions is never allowed to interfere with the immediate demands of empire. Ask Mr. Gandhi or Mr. de Valera. They will confirm this view.

One psychological factor helping the British in their imperial rule is their innate, impregnable unassimability. Once an Englishman, always an Englishman. I have met British officials, British merchants, who have lived in Malaya or Baluchistan for forty years; for all the effect on their character, their habits, they might have spent all that time in Nottingham or Bournemouth. The British Empire is the furthest possible remove from a melting pot. The British do not Mix.- p. 316

- The threat of Italian naval power in the Mediterranean, the dangerous entrenchment given Germany near Gibraltar as a result of the Spanish civil war, the riotous instalibility in Palestine, above all the Munich "peace" in September, 1938, and its consequences, gravely weakened British prestige, British power too, all over the world, as we well know. As a friend of mine said: "The lion tried to show his teeth, and it was all bridgework." In fact some teeth were still there. Mr. Chamberlain preferred to smile instead of biting- but he may have to bite before too long.

- p. 316-317

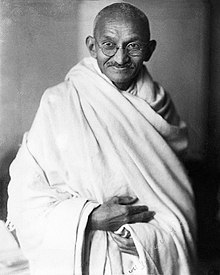

- Mr. Gandhi, who is an incredible combination of Jesus Christ, Tammany Hall, and your father, is the greatest Indian since Buddha. Like Buddha, he will be worshiped as a god when he dies. Indeed, he is literally worshiped by thousands of his people. I have seen peasants kiss the sand his feet have trod. No more difficult or enigmatic character can easily be conceived. He is a slippery fellow. I mean no disrespect. But consider some of the contradictions, some of the puzzling points of contrast in his career and character. This man who is at once a saint and a politician, a prophet and a superb opportunist, defies ordinary categories. For instance, his great contribution to India was the theory and practice of non-violence or civil disobedience. But at the very time that non-violence was the deepest thing he believed in, he was supporting Britain in the World War. The concept of non-violence is a perfect example of Gandhi's familiar usage of moral weapons to achieve practical results, of his combination of spiritual and temporal powers. India, an unarmed state, could make a revolution only by non-violent means. Non-violence was a spiritual concept, but it made revolution practicable.

- p. 345

- Finally, Pan-Asia is an illusion. One can speak of Europe- even now- as a whole. But not Asia. One can speak of such a concept- at least till recently- as a "European mind." I do not think one would readily use such a phrase as an "Asiatic mind." A war in Spain can send tremors throughout Europe as far as the Baltic and beyond; a war in China is still only of remote, vestigal interest to the Asia of the Near East. Asia is not interlocked, intertwined, as Europe is, though it is interlocked with Europe. The Japanese are on the march- even in Tehran I saw a brand of Japanese canned goods known as Geisha sardines- but Asia is a long distance around. It is too big to be a unit. It is three continents in one.

- p. 575

1940s

[edit]Inside U.S.A. (1947)

[edit]- New York: Harper & Brothers, hardcover.

- So now we come to New York City, the incomparable, the brilliant star city of parodies, the forty-ninth state, a law unto itself, the Cyclopean paradox, the inferno with no out-of-bounds, the supreme expression of both the miseries and the splendors of contemporary civilization, the Macedonia of the United States. It meets the most severe test that may be applied to definition of a metropolis- it stays up all night. But also it becomes a small town when it rains. Paradox? New York is at once the climactic synthesis of America, and yet the negation of American in that it has so many characteristics called un-American. One friend of mine, indignant that it seems impossible for any American city to develop on the pattern of Paris or Vienna, always says that Manhattan is like Constantinople- not the Instanbul of old Stamboul but of the Pera or Levantine side. He meant not merely the trite fact that New York is polygot, but that it is full of people, like the Levantines, who are interested basically in only two things, living well and making money. I would prefer a different analogy- that only Instanbul, of all the cities in the world, has as enchanting and stimulating a profile.

- p. 549

- New York is the publishing center of the nation; it is the art, theater, musical, ballet, operatic center; it is the opinion center; it is the radio center; it is the style center. Hollywood? Hollywood is nothing more than a suburb of the Bronx, both financially and from a view of talent. Politically, socially, in the world of ideas and in the whole world of entertainment, which is a great American industry needless to say, New York sets the tone and pace of the entire nation. What books 140 million Americans will read is largely determined by New York reviewers. Most of the serious newspaper columns originate in or near New York; so do most of the gossip columns, which condition Americans from Mobile to Puget Sound to the same patterns of social behavior. In a broad variety of fields, from serous drama to what you will hear on a jukebox, it is what New York says that counts; New York Opinion is the hallmark of both intellectual and material success; to be accepted in this nation, New York acceptance must come first. I do not assert that this is necessarily a good thing. I say merely that it is true. One reason for all this is that New York, with its richly cosmopolitan population, provides such an appreciative audience. It admires artistic quality. It has a fine inward gleam for talent. Also New York is a wonderfully opulent center for bogus culture. One of its chief industries might be said to be the manufacture of reputations, many of them fraudulent.

- p. 549-550

- More than anywhere else in this book, the author must now steer between Scylla and Charybdis, between saying too much and too little. How can we talk about the Statue of Liberty without seeming ridiculously supererogatory? But how can we omit Brooklyn Bridge and still give a fair, comprehensive picture? One must either take the space to mention something that everybody knows everything about, or else risk omission of things that everybody will think ought to be included. Park Avenue in summer near Grand Central, a thin quivering asphalt shelf, and the asphalt soft, a thin quivering layer of street separating the automobiles above from the trains below; avenues as homespun with small exquisite shops as Madison and streets as magnificent as 57th; the fat black automobiles doubleparked on Fifth Avenue on sleety afternoons; kibitzers watching strenuously to see if the man running will really catch the bus; bridges soaring and slim as needles like the George Washington; the incomparable moment at dusk when the edges of tall buildings melt invisibly into the sky, so that nothing of them can be seen except the lighted windows; the way the pace of everything accelerates near Christmas; how the avenues will be cleared of snow and actually dry a day after a six-inch fall, while the side streets are banked solid with sticky drifts; how the noon sun makes luminous spots on the rounded tops of automobiles, crowded together on the slope of Park Avenue so that they look like seashells; the shop that delivers chocolates by horse- all this is too familiar to mention.

- p. 551

- It is a proud boast of New York that, what with its enormous pools of foreign-born, any article or object known in the world may be found there. You can buy anything from Malabar spices to stamps from Mauritius to Shakespeare folios. A stall on Seventh Avenue sells about a hundred different varieties of razor blades. Also it is incomparably the greatest manufacturing town on earth; in an average year it produces goods valued at more than four billion dollars.

- p. 553

- I went down to the City Hall the other day and had an hour with O'Dwyer after not having seen him for several years. He is a shade grayer, a shade stockier, and still a grand man to talk to- easy-going, bluff, friendly, and informal. He wore a light brown sports jacket; he was as relaxed- working a fourteen-hour day- as a character in A Crock of Gold. O'Dwyer has heavy, very short, blunt fingers, a decisive nose, and expressive, eloquent blue eyes. He is full of Irish wit and bounce. Also he is very modest. Mostly we talked about things personal. But occasionally there were remarks like, "How the hell does democracy work, anyway?" This was not, I hasten to add, said with any lack of faith. The mayor is a very gregarious man, and he loves people; especially he loves those who have fought their way out of a bad environment. What he hates most are stuffy people.

- p. 562

- New York City has more trees (2,400,000) than houses, and it makes 18,200,000 telephone calls a day of which about 125,000 are wrong numbers. Its rate of divorces is the lowest of any big American city, less than a tenth of that of Baltimore for instance, and even less than that in the surrounding countryside. One of its hotels, built largely over railway tracks, has an assessed valuation of $22,500,000 (there are 124 buildings valued at more than a million dollars in Manhattan alone), and it is probably the only city in the world that still maintains sheriff's juries and has five district attorneys. New York City has such admirable institutions as New School for Social Research, the Council on Foreign Relations, Cooper Union, the Museum of Modern Art, and a black market in illegitimate babies. It has 492 playgrounds, more than 11,000 restaurants, 2,800 churches, and the largest store in the world, Macy's, which wrote 40,328,836 sales checks in 1944, and serves more than 150,000 customers a day. It has the Great White Way, bad manners, 33,000 schoolteachers (average pay $3,803) and 500 boy gangs.

- p. 577

- New York makes three-quarters of all the fur coats in the country, and its slang and mode of speech can change hour by hour. It has New York University, a wholly private institution which is the second-largest university in the country, 13,800 Jews in its student body, 12,000 Protestants, and 7,200 Catholics, and a great municipal institution, the City College of the College of the City of New York, one of four famous city colleges. In New York people drink 14 million gallons of hard liquor a year, and smoke 20 billion cigarettes. It has 301,850 dogs, and one of its unsolved murders is the political assassination of Carlo Tresca. New York has 9,371 taxis and more than 700 parks. Its budget runs to $175,000,000 for education alone, and it drinks 3,500,000 quarts of milk a day. The average New York family (in normal times) moves once every eighteen months, and more than 2,200,000 New Yorkers belong to the Associated Hospital Service. New York has a birth every five minutes, and a marriage every seven. It has "more Norwegian-born citizens than Tromsoe and Narvik put together," and only one railroad, the New York Central, has the perpetual right to enter it by land. It has 22,000 soda fountains, and 112 tons of soot fall per square mile every month, which is why your face is dirty.

- p. 577

- Fiorello Henrico LaGuardia, the most spectacular mayor the greatest city in the world has ever had, has characteristics and qualities so obvious that they are known to everyone- the volatile realism, the rubble-supple grin, the flamboyant energy, the zest for honesty in public life, the occasional vulgarisms, the common sense. But the mayor I spent these uninterrupted hours with showed more conspicuously some qualities for which he is not so widely known. He picked what he called a "desk day" for me to sit in on. He did not inspect a single fish market or visit a single fire. What he did was work at his major job, administration of the city of New York. What he did was to govern, to put in a routine day as an executive.

- p. 578

- Fiorello H. LaGuardia is one of the most original, most useful, and most stimulating men American public life has ever known.

- p. 588

- Famously the South is the land of demagogues, of cumulus-cloudy politicians who emit wads of opaque cotton every time they open their mouths. Think back a little, to the time when men now mostly forgotten were household names- "Cotton Ed" Smith of South Carolina, who was probably the worst senator who ever lived, no mean honor; Tom Watson of Georgia and Tom Heflin of Alabama, one of the most fanatic reactionaries in American history, especially about things religious; John Sharp Williams of Mississippi, Cole L. Blease of South Carolina, one of the typical "spittoon senators," and of course Huey Long of Louisiana.

- p. 675

- In Athens, Alabama, in August, 1946, two white boys and a Negro had a scuffle. An honest white policeman refused to arrest the Negro, on the ground that he was not the aggressor; he did arrest the whites. A mob numbering between 1,800 and 2,000 thereupon stormed the city hall, forced the release of the white boys, and began to riot; Negroes were chased off the streets and between fifty and one hundred were injured. When order was restored nine whites were taken into custody on charges of "unlawful assembly." They were released later. Eight were teen-agers; the youngest, thirteen years old, "carried a club and knocked Negroes down."

- p. 685

- On February 12, 1946, a Negro veteran named Isaac Woodard, who had received his honorable discharge papers only a few hour before and who was still in uniform, took a bus at Atlanta for his home in South Carolina. When the bus stopped at a hamlet Woodard asked the driver if he could go to a rest room. The driver refused and a violent quarrel ensued. At the next stop, Batesburg, South Carolina, the driver called a policeman, saying that Woodard had made a disturbance; the policeman took him off the bus, started beating him, carted him off to jail, and ground out his eyes with the end of his club. This case too became a country-wide scandal. A mass rally held in the Lewisohn Stadium in New York raised a purse of $22,000 for the blinded veteran. It did not restore his vision. Attorney General Clark and the FBI instituted an investigation, after much public clamor, and the Batesburg police officer was identified, arrested, and brought to trial. His name was, and is, Lynwood E. Shull. The charge, brought "in a criminal information filed by the Department of Justice," was that Shull violated Woodard's "civil rights" by beating him. Shull's reply was that he had acted in self-defense. A United States district court jury acquitted Shull in half an hour.

- p. 686

- Another type of mob outrage sometimes occurs in the South; clandestine or "underground" lynching in which a Negro who has broken taboos simply disappears. There is no corpus derilicti, and no scandal. The body is never found, and people say that the victim has "moved" somewhere. For a time members of the Ku-Klux Klan were most distinguished for this kind of affair.

- p. 686

- The effect of World War II is one point worth noting. Almost every victim of lynching since the war has been a veteran. The Negro community is probably more unified today, more politically vehement, more aggressive in its demand for full citizenship- even in the South- than at any other time in history. Roughly one million Negroes entered the armed services. They moved around and saw things; they were exposed to danger and learned what their rights were; overseas, many were treated decently and democratically by whites for the first time in their lives; the consequent fermentations have been explosive. Also since Negroes were presumably fighting for democratic principles on the international plane, it was difficult to keep them from wondering why the same principles were not applied at home. It wasn't easy for an intelligent Negro to accept that he was fighting for democracy- in a largely Jim Crow army. The glaring crudity of this paradox became the more striking as the war went on. One famous remark is that of the Negro soldier returning across the Pacific from Okinawa. "Our fight for freedom," he said, "begins when we get to San Francisco."

- p. 687

- One familiar Southern attitude is, "The Negro is our problem. We have to live with it, and let us solve it." Also Southerners say, "You can never understand it." Indeed, interference or advice from the North is tenaciously resented. Yet, no matter what the South may have done of itself, the record would certainly seem to indicate that it is not enough. Another familiar phenomenon is the "vicious circle" attitude. People refuse to give opportunities to a Negro, on the a priori assumption that he cannot make use of them, blaming him all the while. The pattern becomes, "We cannot train Negroes for this type of work, since they won't be able to do it if we train them!"

- p. 698

- One thing, it would seem, is certain. The days of treating Negroes like sheep are done with. They cannot be maintained indefinitely in a submerged position, because the overwhelming bulk of white Americans are, in the last analysis, decent minded, and because of education. It is impossible at this stage to halt education among Negroes. But the more you educate, the more you make inevitable a closer participation by Negroes in American life as a whole. In slightly different terms, this is the problem that the British Empire has faced in various colonial areas; once mass education gets under way the route to freedom becomes open, and the more you educate, the more impossible it becomes to block this road. The United States must either terminate education among Negroes, an impossibility, or prepare to accept the eventual consequences, that is, Negro equality under democracy. There will never be a "solution" to the Negro problem satisfactory to everybody. But improvements, no matter how fitful, must continue if American democracy itself is to survive. Discrimination not only contaminates the Negro community; it contaminates the white as well. There were people in the Middle Ages who thought that the bubonic plague would not spread to their own precious selves. But there is no immunity to certain types of disease. A cancer will destroy the body, unless cured.

- p. 704

- Incontestably what runs Virginia is the Byrd machine, the most urbane and genteel dictatorship in America. A real machine it is, though Senator Harry Flood Byrd himself faced more opposition in 1946 than at any time in his long, suave, and distinguished public career. Virginia is, of course, "the mother of states"; it is one of four in the union to call itself a commonwealth, and it has produced eight presidents, more than any other state. Its history goes back to Jamestown, the first Anglo-Saxon settlement in America, in 1607; the colony was named for Elizabeth, the virgin queen, and its citizens established an effective representative government several years before the Puritans in New England. Ever since it has prided itself on aristocratic tradition, a seasoned attitude toward public life, administrative decency, and firm attachment to the regime of law. Virginia breeds no Huey Longs or Talmadges; its respect for the forms of order is deeply engrained. One subsidiary point is that Virginians, it seems, were not so philoprogenitive as their New England counterparts. Boston, as we know, choked with Cabots, Adamses, and Lowells. But there are no Washingtons in Richmond; George Washington, as a matter of fact, left no children. Jefferson had direct descendants, but none with the name Jefferson play any consequential role in Virginia life today. There are no Madisons, Monroes, descendants of John Marshall or Patrick Henry, or even Lees, in the contemporary political arena.

- p. 705

- The West Virginia motto is Montani semper liberi, and the state is one of the most mountainous in the country; sometimes it is called the "little Switzerland" of America, and once I heard an irreverent local citizen call it the "Afghanistan of the United States." The precipitous upland nature of the terrain makes naturally for three things: (1) poor communications; (2) fierce sectionalism; (3) comparatively little agriculture. West Virginia lies mostly in the Ohio orbit; all but eight of its counties drain into the Ohio River, and a pressing problem is strip mining, as in Ohio. On the other hand, the state has, it is hardly necessary to point out, little of the prodigious urban development of Ohio, and at the same time no great rural blocs such as those that dominate the Ohio legislature. The pull of Pennsylvania is also very strong, particularly near Wheeling which, like Pittsburgh hard by, is based on steel. Finally, in this geographical realm, one should not think of West Virginia as being "western" Virginia. It is a totally distinct and separate entity. Virginians themselves, as a matter of fact, pay almost no attention nowadays to their craggy neighbor.

- p. 715

- The more one looks back to it, the more noteworthy it all seems. It is easy to be wise after the event; it is also (as somebody once said) wise. In almost every respect the career of Huey Long parallels that of the modern European dictator-tyrant, the Hitler or Mussolini. Huey Long, had he lived, might very well have brought Fascism to America.

- p. 809

- There are at least four main points to be made about the Lone Star State all at once. It does not properly belong to the South, the West, or even the Southwest; it is an empire, an entity, totally its own.

- p. 814

- American scientists are ceaselessly attacking in every sphere the frontiers of the unknown; American economists and social engineers have at hand techniques that can forestall a new depression; there is no valid reason why the American people cannot work out an evolution in which freedom and security are combined. Creative good will, coherent large-minded planning, clarity of vision, a grasp of the realities of the nation as a whole, spring-mindedness, education and more education, a fixed national purpose to make out of contemporary civilization weapons that will cure, not kill- all this is possible. In a curious way it is earlier, not later, than we think. The fact that a third of the nation is ill-housed and ill-fed is, in simple fact, not so much a dishonor as a challenge. What Americans have to do is enlarge the dimensions of the democratic process. This country is, I once heard it put, "lousy with greatness"- with not only the greatest responsibilities but with the greatest opportunities ever known to man.

- p. 920

1950s

[edit]Roosevelt in Retrospect: A Profile in History (1950)

[edit]- Franklin Delano Roosevelt, thirty-second President of the United States and Chief Executive from 1933 to 1945, the architect of the New Deal and the director of victory in World War II, Franklin Delano Roosevelt who is still both loved and hated as passionately as if he were still alive, was born in Hyde Park, New York, in 1882, and died in Warm Springs, Georgia, in 1945. It was his fate, through what concentration of forces no man can know, to be President during both the greatest depression and the greatest war the world has ever known. He was a cripple- and he licked them both.

- p. 3

- To a supreme degree Roosevelt had five qualifications for statesmanship: (a) courage; (b) patience, and an infinitely subtle sense of timing; (c) the capacity to see the very great in the very small, to relate the infinitesimal particular to the all-embracing general; (d) idealism, and a sense of fixed objectives; (e) the ability to give resolution to the minds of men. Also he had plenty of bad qualities- dilatoriness, two-sidedness (some critics would say plain dishonesty), pettiness in some personal relationships, inability to say No, love of improvisation, garrulousness, amateurism, and what has been called "cheerful vindictiveness." Amateurism?- in a particular way, yes. But do not forget that he was the most masterfully expert practical politician ever to function in this republic.

- p. 5

- One of FDR's most heart-warming qualities was his almost illimitable gift for friendship, which arose out of his idealism, his innate delight in life, and his generosity. His friends were of the widest possible variety, from formidable old crustaceans like Admiral King to courageous, incisive women like Anna Rosenberg to columnists like Walter Winchell.

- p. 81

- If anybody ever doubted that Roosevelt was a good bluffer, events after Pearl Harbor should set the record straight. For almost a year the United States had no fleet worthy of the name in the Pacific, but no one, least of all the Japanese, ever caught on to how miserably defenseless we really were.

- p. 324

- Roosevelt was a man of his times, and what times they were!- chaotic, catastrophic, revolutionary, epochal- he was President during the greatest emergency in the history of mankind, and he never let history- or mankind- down. His very defects reflected the unprecedented strains and stresses of the decades he lived in. But he took history in his stride; he had vision and gallantry enough, oomph and zip and debonair benevolence enough, to foresee the supreme crises of our era, overcome them, and lead the nation out of the worst dangers it has ever faced. Roosevelt was the greatest political campaigner and the greatest vote getter in American history. Thirty-one out of forty-eight states voted for him each of the four times he ran. His influence, far from having diminished since his death, has probably increased. When Mr. Truman won his surprising victory in 1948, which was made possible in part by the political influence left behind by FDR, it was altogether fitting that a London newspaper should head its story, "Roosevelt's Fifth Term."

- p. 378

- Roosevelt believed in social justice- and fought for it- he gave hope and faith to the masses, and knew that the masses are the foundation of American democracy. He turned the cornucopia of American resource upside down and made it serve almost everybody. Mrs. Roosevelt has said that in the course of his whole career there was never any deviation from his original objective- "to make life better for the average man, woman, and child." I have heard men of the utmost sober conservatism say that they think FDR saved the country from overt revolution in 1932. He created the pattern of the modern democratic state, and made it function. To be a reformer alone is not enough. A reformer must make reform effective. This certainly Roosevelt did.

- p. 378

- Also, Roosevelt's career nicely disproves an essential constituent of Marxism, namely the principle of class war. His entire life refutes the Marxist thesis. He was a rich man and an aristocrat; but he did more for the underpossessed than any American who ever lived. Moreover, as we know, FDR always operated within the framework of full democracy and civil liberties. He believed devoutly in the American political tradition. Much of the world outside the United States during his prodigious administrations had political liberty without economic security; some had security but no liberty. Roosevelt gave both. Mr. Roosevelt was the greatest war president in American history; it was he, almost singlehanded, who created the climate of the nation whereby we were able to fight at all. Beyond this he brought the United States to full citizenship in the world as a partner in the peace. He set up the frame in which a durable peace might have been written and a new world order established; if he had lived to fill in the picture contemporary history might be very different. Above all, FDR was an educator. He expanded and enlarged the role of the Presidency as no president before him ever did. "The first duty of a statesman is to educate," he said in his Commonwealth Club speech back in 1932. He established what amounted to a new relationship between president and people; he turned the White House into a teacher's desk, a pulpit; he taught the people of the United States how the operations of government might be applied for their own good; he made government a much abler process, on the whole, than it has ever been before; he gave citizens intimate acquaintanceship with the realities of political power, and made politics the close inalienable possession of the man in every street. One result of all this is that the President, though dead, is still alive. Millions of Americans will continue to vote for Roosevelt as long as they live.

- p. 379